Lieutenant Colonel │ Second World War │ Malaya │ 2/13th Australian General Hospital

Family background

Vivian Bullwinkel Statham AO MBE ARRC ED was born on 18 December 1915 in Kapunda, a town near the Barossa Valley in South Australia. She was the daughter of Eva Kate Shegog (1888–1981) and George Albert Bullwinkel (1879–1934).

Eva was born in Port Augusta in South Australia. Her mother, Emily, was born in Australia and her father, William, in Ireland. William migrated to Victoria with his parents as a young boy and became a farmer in Victoria before moving to Adelaide, where he joined the South Australian Police Force. He worked in many rural and remote towns and attained the rank of inspector. After retiring around 1920 he and Emily moved to Prospect in Adelaide.

George was born in Leytonstone, England. He arrived in New South Wales when he was around 18 years old and worked as a bookkeeper for about 13 years on Mutooroo Station in South Australia, around 100 kilometres southwest of Broken Hill in western New South Wales. He then worked as a clerk and timekeeper at the De Bavay mine in Broken Hill for about 13 years and finally as a clerk in the store of the South mine in Broken Hill.

George was introduced to Eva through her brother, William, and the two were married on 16 April 1914 at St. Paul’s Church in Adelaide and then lived in Broken Hill.

Early Life

The following year Vivian was born in Kapunda, where Eva Bullwinkel’s father was stationed. After her birth the family returned to Broken Hill, and here Vivian’s brother, John William (Jack) Bullwinkel, was born in 1920.

In 1922 Eva and George decided that Vivian, who had briefly attended North Broken Hill School, would receive a better education in Adelaide. They sent her to live with Eva’s parents, William and Emily Shegog, in Prospect. She attended Prospect Primary School until the end of 1927 and then returned to her parents in Broken Hill.

In 1928 Vivian began attending Broken Hill High School and in 1932 and 1933 was named a school prefect. In 1933, her final year, she was also elected one of two school captains. During her time at high school Vivian did not demonstrate particular academic aptitude but she did excel at sports. She played basketball and was always among the goal throwers; tennis, at which she was also very good; and vigoro, an unusual sport, a cross between cricket and tennis invented in 1901 and played exclusively by women.

NURSING

After finishing high school with her Leaving Certificate, Vivian considered a career in telephony before following her friend Zelda Treloar into nursing. They both became probationers at Broken Hill and District Hospital. Among the senior nurses at the hospital was Sister Irene Drummond, sister-in-charge of the male surgical ward, where she treated many victims of mining accidents. Later, Irene Drummond would be Vivian’s matron at the 2/13th Australian General Hospital (AGH) when they both served with the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) in Malaya.

Tragedy was visited upon the Bullwinkel family on 18 September 1934 when George Bullwinkel suffered a heart attack in a taxi on the way home from a meeting of the Broken Hill Masonic Club. He died in hospital some hours later and was interred the following day at the Church of England Cemetery. At the time of his death, George was still working as a clerk at the South mine.

Vivian graduated from Broken Hill and District Hospital with her Nurses’ Registration Certificate on 16 December 1937 and became registered in general nursing on 24 February 1938. She immediately undertook midwifery training and became registered as a midwife on 30 March 1939.

After obtaining her midwifery registration, Vivian moved to Victoria’s Western District to take up a position as staff nurse at Kia-Ora Private Hospital in Hamilton. She stayed there for some time, then in 1940 moved to Melbourne to work at the Guildford Private Hospital in Camberwell. Finding this somewhat dull, she joined the staff of the Jessie McPherson Hospital in central Melbourne, where she met Senior Sister Olive Dorothy Paschke, known as Dot. By now war had broken out in Europe, and Dot Paschke was soon to serve as matron of the 2/10th AGH and senior AANS nurse in Malaya.

ENLISTMENT

Vivian wanted to serve her country too. While still at Jessie McPherson, she applied to join the RAAF Nursing Service but was rejected, so joined the AANS instead. She was appointed to the Australian Military Forces (AMF) for home service with the AANS and on 20 May 1941 was posted to the 107th AGH at Puckapunyal, 100 kilometres north of Melbourne. Among the other nurses posted to Puckapunyal after appointment to the AMF were Staff Nurses Gladys Hughes from New Zealand via Melbourne and Joan Wight from Fish Creek in Victoria. Both would soon serve with Vivian in the 2/13th AGH.

In early August, Australian military authorities approved a request for the deployment of a second military hospital to Malaya to support the 2/10th AGH, which had sailed on the Queen Mary with the 8th Division, Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF) in February and was based in Malacca. Accordingly, the 2/13th AGH was raised in Melbourne with staff chosen from across the country. Forty-nine AANS nurses were selected to join the unit, with Vivian, Gladys and Joan among them. Their respective appointments to the AMF were terminated on 31 August upon their transfer the following day to the 2nd AIF. They were going overseas.

That same day, 1 September, Vivian, Gladys and Joan were taken by bus from Puckapunyal to the Lady Dugan Hostel in South Yarra, Melbourne, where AANS nurses from Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania were being billeted prior to embarkation and departure the next day. Among them were Sister Elizabeth Simons from Tasmania and Staff Nurse Wilma Oram from Victoria.

At approximately 9.00 am on the morning of 2 September Vivian and the others were taken by bus from South Yarra to Port Melbourne, where they boarded HMAHS Wanganella. The newly commissioned hospital ship had left Sydney on 30 August with a contingent of 2/13th AGH personnel from New South Wales and Queensland that included 19 AANS nurses. At around 5.00 pm the Wanganella slipped out of Port Phillip Bay and headed into Bass Strait. Six days later it pulled into Fremantle, where seven more AANS nurses joined the cohort. They were now 49.

After leaving Fremantle those on board were officially told that their destination was Malaya, and some expressed disappointment at the thought that they would not ‘see action.’ They could not have known how wrong they were.

MALAYA

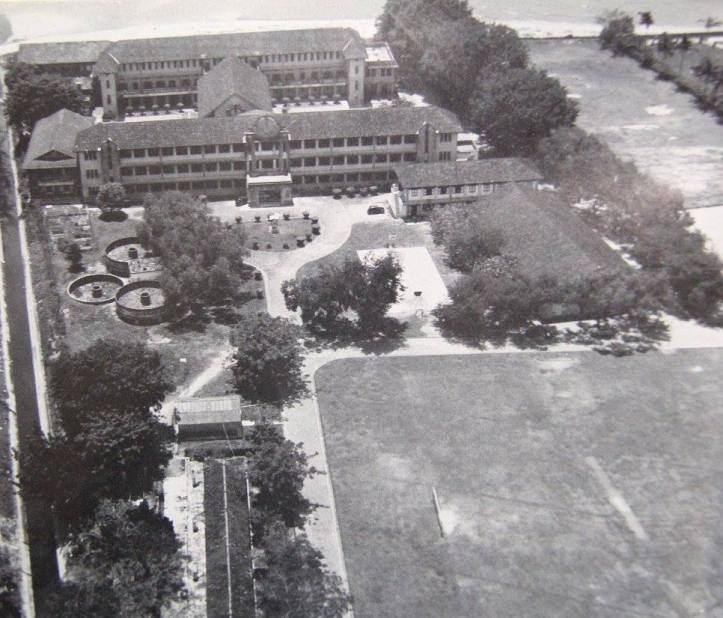

The Wanganella arrived at Victoria Dock on Singapore Island on 15 September, and Vivian and nine other nurses, much to their dismay, were detached to the 2/10th AGH in Malacca and stayed on the ship. The others disembarked and were met by Colonel Wilfrid Kent-Hughes, Assistant Adjutant and Quartermaster General of the 8th Division, who had organised buses to transport them to St. Patrick’s School in Katong, on the island’s south coast. Here the 2/13th AGH would be billeted while it waited to be sent to its permanent home, the Tampoi Mental Hospital on the outskirts of Johor Bahru in the south of the Malay Peninsula.

Soon Vivian and the other nine nurses disembarked too and were taken to the station at Keppel Harbour, where they boarded a train for the town of Tampin on the Malay Peninsula. From Tampin they were taken by car to the Malacca General Hospital in the old colonial town of Malacca, where the 2/10th AGH was based.

The 10 nurses – dubbed the “mobile 10” by Tasmanian Mollie Gunton, who was among them – stayed at the 2/10th AGH for three weeks learning tropical nursing from their experienced 2/10th AGH peers. They treated such maladies as tropical ulcers, dengue fever and the odd case of malaria, and upon their return to St. Patrick’s passed on their newfound knowledge to the orderlies.

When Vivian and the other nine returned to St. Patrick’s on 6 October, another contingent of nurses was detached to the 2/10th AGH, and this would be the pattern over the next three months. Other nurses were detached to the 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station (CCS), which had sailed on the Queen Mary with the 2/10th AGH in February and was based at the time in Kajang, just south of Kuala Lumpur on the peninsula.

Meanwhile Vivian had been reunited with Irene Drummond from Broken Hill Hospital. Irene had been senior sister of the 2/4th CCS, but shortly after the arrival of the 2/13th AGH was appointed the unit’s matron.

While their colleagues were on detachment to the 2/10th AGH and the 2/4th CCS, the nurses at St. Patrick’s were attending lectures, going on field trips to hospitals on the island, and instructing their orderlies in general nursing techniques. They were also enjoying plenty of leisure time. They played tennis and golf and were granted access to the exclusive Singapore Swimming Club. They were wined and dined by officers and wealthy Singapore residents. On 18 October Vivian and her 2/13th AGH colleague Staff Nurse Nancy Harris were taken out by two officers to nearby Amber Road for drinks and then to Raffles for dinner. After dancing at Raffles for a time the party went to Coconut Grove for more dancing and then back to Amber Road for a nightcap. On another occasion Vivian and Nancy were invited by British expatriates Peg and Richard Hanson to accompany them to dinner on a ship in Keppel Harbour. They were taken out to a luxury yacht owned by Sir Charles Vyner Brooke, the so-called White Rajah of Sarawak. It was named the Vyner Brooke. On board they met the second officer, Jimmy Miller.

On 7 November Vivian was detached again, this time to the 2/4th CCS, which by now had moved into the psychiatric hospital in Tampoi earmarked for the 2/13th AGH. The rambling, single-story complex of concrete buildings had been leased from the Sultan of Johor and was partially surrounded by jungle; it was not unusual for scorpions, centipedes and other creatures to wander inside. Two weeks later, the 2/13th AGH finally received orders to proceed to Tampoi, and over the weekend of 21–23 November 100 tons of equipment was transported there from Katong. Once the move had been completed, Vivian rejoined her unit. In the meantime, the 2/4th CCS had relocated 100 kilometres north to Kluang, where the unit established its hospital at the town’s aerodrome next to a civilian hospital.

War

By late November Japanese troops had massed in French Indochina, and all the signs pointed to war. On 1 December the codeword ‘Seaview’ was issued, advancing all Commonwealth forces in Malaya to the second degree of readiness. All leave was cancelled and units had to be ready to move at a few hours’ notice to their war stations. On 6 December the codeword ‘Raffles’ was given, indicating advancement to the first degree of readiness. At around the same time the Australian crew of No. 1 Squadron RAAF, flying out of the RAF base in Kota Bharu on the northeastern coast of Malaya, reported the presence of a Japanese fleet in the Gulf of Thailand. War was imminent.

It came within 36 hours. At around 12.30 am on 8 December troops from General Yamashita’s 25th Army made coordinated amphibious landings at Kota Bharu and at Pattani and Singora (Songkhla) in Thailand. At Kota Bharu the 8th Indian Infantry Brigade offered stiff ground resistance, while No. 1 Squadron RAAF bombed and strafed the landing force, but ultimately to no avail, and before long Japanese forces had established a beachhead. Meanwhile, the landings in Thailand were unopposed, and Japanese forces immediately proceeded inland. Then at around 4.30 am 17 Japanese bombers, flying from southern Indochina, attacked targets on Singapore Island, including air bases at Tengah and Seletar in the north of the island. Raffles Place in Singapore city was also hit, killing 61 people and injuring hundreds, mainly soldiers. Some of the 2/13th AGH nurses at Tampoi witnessed the attack. Elsewhere, Pearl Harbour, Guam, Midway, Wake Island and American installations in the Philippines were attacked and Hong Kong was invaded. Japan declared war on the United States, Great Britain, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa. The Pacific War had begun.

The three-pronged Japanese invasion force soon began to move southwards. From Kota Bharu Japanese troops began to advance down the eastern side of the Malay Peninsula, while from Pattani and Singora the invading troops crossed into Malaya and began to advance down the peninsula’s western side. Backed by mechanized units and devastating air power, the three columns of well-trained, combat-ready Japanese troops forced severely outgunned British and Indian troops to retreat before them. Without air cover, they never had a chance.

On 12 December the 2/13th AGH received a memo from Lieutenant Colonel J. G. Glyn White, Deputy Assistant Director of Medical Services (ADMS), 8th Division, ordering the hospital to expand from 600 to 1,200 beds. By 15 December two new wards had been set up. Staff were also required from then on to wear Red Cross armbands, and the nurses were no longer allowed outside the hospital compound after dark, nor were they allowed visitors.

As the war became hotter and closer, Vivian and her colleagues quickly became used to interrupted sleep, blackouts and air-raid warnings. Some of the nurses were formed into a signals squad, whose job it was to ring a large brass bell upon receiving the message ‘Air Raid Red’ from the Army Signals Corps, whereupon the nurses and their amahs (housemaids) would head for the cover of the jungle. Others formed a decontamination squad.

Christmas came as a welcome distraction. The wards at Tampoi were decorated, and the patients’ rations were boosted for the festive event. The officers helped to carve the poultry and ham and helped the nurses to serve the bed patients. They also made the nurses sit down with the up patients and waited on them. In return the nurses arranged a party in their mess for the officers and on Boxing Day a larger party for the troops.

Events sped up after Christmas. In the face of Japan’s unstoppable push southwards, it became clear that the 2/10th AGH at Malacca would have to evacuate to Singapore Island, and staff and patients were moved south in stages. Between 29 December and 5 January 1942, 36 nurses and around 40 other staff joined Vivian at the 2/13th AGH, bringing scores of patients with them. Twenty more were detached to the 2/4th CCS, which had moved from Kluang aerodrome to Mengkibol Estate, a few kilometres outside Kluang. By 15 January the 2/10th AGH had completed its move to the island, and soon after most of the detached nurses rejoined the unit.

On the evening of 16 January, the war hit the 2/13th AGH hard. Two days previously, Australian troops had entered combat for the first time, and after achieving a tactical victory against a Japanese force at Gemas, fought much bloodier battles over the following two days. Soon, convoys of casualties on stretchers with tickets pinned to them showing the most urgent injuries began to flow to Tampoi via the 2/4th CCS. The admission room quickly established identity, rank and injury, then stretcher bearers ran the wounded to either a ward or an operating theatre. The unit had worked hard to prepare operating theatres to receive them and had by now very nearly fulfilled the 1,200-bed stipulation.

Retreat to Singapore

On 21 January, Lieutenant Colonel Glyn White, in consultation with Colonels Edward Rowden White and Douglas Clelland Pigdon, commanding officers of the 2/10th and 2/13th AGHs respectively, instructed the 2/13th AGH to evacuate to Singapore Island. After some discussion it was decided to return to St. Patrick’s School, and a handful of Vivian’s colleagues were sent there to clean and prepare it for the unit’s arrival. Abandoned bungalows adjoining the school were cleaned in preparation for their use as staff quarters.

The relocation took place over the weekend of 24–25 January. The final convoy, carrying medical patients, arrived late on Sunday night. Matron Irene Drummond had ensured that beds had been made, pyjamas and towels placed at the ready, cold drinks and sandwiches prepared, and teapots warmed up. By midnight all patients were safely bedded down. The move had been a startling success.

On 28 January the 2/4th CCS followed the other two medical units to Singapore Island, relocating to Bukit Panjang English School. Two days later the final Commonwealth troops crossed the Causeway from the Malay Peninsula to Singapore Island, and the next morning it was blown up. Within a little more than a fortnight, Singapore would fall.

Japanese troops reached the northern shore of Johor Strait soon after the demolition of the Causeway and began a ferocious artillery bombardment of the island. They crossed the strait on the night of 8 February and by the morning had established a beachhead on the northwestern corner of Singapore island, despite strong opposition from Australian troops.

Vivian and her colleagues were now working under extreme pressure. With convoys of ambulances arriving at St. Patrick’s with hundreds of wounded soldiers, the hospital became so overcrowded that outbuildings and even tents were used as wards. Casualties lay closely packed on mattresses on floors and even outside on the lawns, the majority with gunshot and shrapnel wounds. The nurses worked 12-hour shifts, and the theatre, blood bank and x-ray nurses worked even longer. When they did eventually finish their shifts, the constant air-raids, bombings and artillery barrages made sleep hard to come by.

The Last days of Singapore

Early in the morning of 31 January 1942, after the last Commonwealth troops had crossed the Causeway linking the peninsula to Singapore Island, British engineers blew it in two places in an attempt to slow the Japanese advance onto the island. The first explosion destroyed the lock’s lift-bridge, while the second caused a 21-metre gap in the structure. The extensive damage brought a reprieve of just eight days.

The forces of the Japanese 25th Army were now in complete control of the peninsula and on 2 February began a ferocious artillery bombardment of the island. Singapore’s oil infrastructure was targeted, particularly on the south coast. The resulting fires generated palls of thick black smoke, which hung over the city, creating an eerie twilight.

In the daylight hours of 8 February, Japanese forces concentrated their artillery on the northwestern defence sector of Singapore Island, destroying military headquarters and communications infrastructure. That night, waves of Japanese soldiers crossed Johor Strait and landed in small boats around the mouth of the Kranji River on the northern coast of the island. They were initially repelled by elements of the 2/20th Battalion and 2/4th Machine Gun Battalion, but the Japanese were too numerous. They eventually overwhelmed the Australians, who could not communicate effectively with their command headquarters due to the damage caused that day, and by the morning of 9 February had established a beachhead. Further to the west there was another landing.

Australian casualties began to pour into St. Patrick’s School, mainly with gunshot and shrapnel wounds. For the next 24 hours, the hospital’s surgeons and theatre nurses worked nonstop, carrying out 65 operations. Bombing and shelling were now almost continuous, and as the fighting grew closer, the hospital became so overcrowded that casualties lay closely packed on mattresses on floors, in the quartermaster’s store, in the little chapel, and outside on the lawns. Outbuildings and tents were used as wards. The theatre nurses continued to work long hours, and even the ward nurses worked 12-hour shifts. When they finished, the noise of war made sleep hard to come by.

Some of the wounded soldiers begged the nurses to let them leave the hospital to continue fighting. According to Vivian’s colleague Staff Nurse Frances Cullen, in an interview with the Australian Women’s Weekly in March 1942, “Even the ones with limb injuries said they could be carried to a gun and could lie beside it to fire it.”

With Singapore’s fate now all but certain, a decision was made to evacuate the Australian nurses.

Evacuation of the Nurses

Early on 25 December 1941 between 150 and 200 soldiers of the Imperial Japanese Army entered a 400-bed emergency military hospital established at St. Stephen’s College in the south of Hong Kong Island and proceeded to massacre as many as 100 patients and medical staff. Among the medical staff were two British nurses from the Bowen Road Military Hospital, six British Voluntary Aid Detachments and five Chinese St John’s Ambulance nurses. They were all wearing nurses’ uniforms and Red Cross armbands. The Chinese nurses and three of the British nurses and VADs were raped and then murdered, while the other four were raped but survived.

Reports of the horrific events soon reached Malaya and began to circulate widely; and as Japan’s march south continued, Colonel Alfred P. Derham, Assistant Director of Medical Services for the 8th Division, began to worry. Between 20 and 25 January 1942 he recommended officially to Major General Gordon Bennett that the Australian nurses should be evacuated from Singapore by the first possible hospital ship. He repeated this recommendation between 25 and 30 January. On each occasion his recommendation was rejected on the grounds that if carried out, it would have had a bad effect on the civilian morale of Singapore. Colonel Derham appealed once again on 8 February 1942, this time directly to Lieutenant General Arthur Percival, General Officer Commanding Malaya, and once again his appeal was refused.

At this point Colonel Derham instructed Lieutenant Colonel Glyn White to send as many nurses as he could with any casualties leaving Singapore, and on the morning of Tuesday 10 February six nurses of the 2/10th AGH embarked on the Wusueh with as many as 350 wounded men, including perhaps 150 Australian 8th Division troops, a few RAAF men, and scores of British and Indian troops. Major General Bennett then stated that the remaining nurses should be embarked as soon as practicable.

At St. Patrick’s, meanwhile, Matron Irene Drummond announced at lunchtime on 10 February that all but 12 of the 2/13th AGH nurses were to go that day as well. However, by the time Colonel Pigdon spoke to the nurses at 4.30 pm, the order had changed, and all were now to remain until late morning the following day.

The next day was Wednesday 11 February. In the morning the 2/13th AGH nurses assembled in the grounds of the hospital and were told by Colonel Pigdon and Matron Drummond that they were to be evacuated later that day. When they gathered again in the afternoon Matron Drummond read from a list the names of 30 nurses who were to leave shortly for the docks in a convoy of ambulances. They had no option of either staying with their patients or waiting until such time as all of the nurses could leave together and were told to pack their weekend suitcase and take their respirator, tin helmet and iron rations. This done, they were driven to St. Andrew’s Cathedral or the Adelphi Hotel (sources differ), located close to each other in Singapore city, where they rendezvoused with 30 nurses from the 2/10th AGH. They were then taken to Keppel Harbour, boarded the Empire Star with as many as 2,400 people – mainly British RAF personnel, but also 140-odd 2nd AIF troops and many civilian refugees, including more than 160 women and 35 children – and, like the nurses on the Wusueh, made their escape to Australia. There were now 65 AANS nurses left in Singapore.

Escape on the Vyner Brooke

Late in the afternoon of Thursday 12 February, the remaining nurses were told that they had to go too. At St. Patrick’s School, the 27 nurses of the 2/13th AGH and the four 2/4th CCS nurses on detachment to the unit rushed to get ready. Later, in the early days of her captivity, Vivian found an old notebook and briefly recorded what she could recall of these final days of her former life.

Feb 12th Thurs.

Tray of sweets snatched from hand by Major Holmes and told to go for my life to the quarters – Jenny [Kerr] in middle of preparing leg for amputation – chapel in chaos with dressings … dressing to be done to say nothing of the sponging – Hurried farewell to boys who smiled but were really sad at heart. arriving at quarters quickly changed taking handcase & managed to get the [gramophone?] though into English ambulances – and so a sad farewell [to] St. Pat’s – Cookie Ah Long standing [with] tears running down his cheek ‘How will I know missies come back’ … ‘It’s a bad blue’ as he wandered back to the hospital and … drove out of the girls Goodbye smiles from the [sad?] boys.

The 31 nurses were driven in ambulances from St. Patrick’s School to St. Andrew’s Cathedral in the city, where, during a massive air raid, they met their remaining 2/10th AGH and 2/4th CCS colleagues, numbering 30 and four respectively.

First visit to Singapore since our arrival at St. Pat’s [after returning 25 January 1942] place wrecked [in] many quarters drive to St. Andrew’s Cathedral where we joined the 10th A.G.H. – names taken & told would be leaving in … three [?] days

From the cathedral they continued to Keppel Harbour. As they approached the harbour, the ambulances could go no further due, and the nurses got out and walked the final few hundred metres. At the wharves there was chaos. Hundreds of people – women, children, men – were milling about, attempting to board any vessel that would take them. The 65 nurses were eventually taken by a tug to a small coastal steamer, the Vyner Brooke – the very same boat on which Vivian and Nancy Harris had been entertained. On board there were between 200 and 300 women, children and old and infirm men.

ack ack from ground making us quickly flatten down – we entered ambulance & drove to docks – boys cheering moving along the roads hundred of cars near docks just driving into harbour or [bombed?] – single file along the wharf – a couple of raids – boardered [sic] tug plus [?] & child Drummond takes howling baby from crying mother & fed the infant – waved goodbye to Col [Glyn] White & Capt Abramovitch – stop along side small ship none other than Vyner Brook [sic] – Jimmy Miller on look out for Harris & I give in his cabin & makes us as comf as possible looked after us marvellously well cigarettes whiskey & everything …

As darkness fell, the Vyner Brooke slipped out of Keppel Harbour but became caught in the minefield outside the harbour.

drawing out into harbour & looking back at Singapore place just a mass of flames along water front … Island burning on the other side a terrible & unforgetful [sic] sight – retired early to a disturbed night much shouting & ringing of bells – found out next morning we were lost amongst mine field & only Bill Sedgman [the Vyner Brooke‘s first officer, Lieutenant Bill Sedgeman] good navigating got us through with only the fires to guide him

The Vyner Brooke finally began its hazardous journey south. The better to avoid Japanese spotter aircraft, during the day Captain Richard Borton hid his vessel among the many small islands that line the passage between Singapore and Batavia. On Friday morning the nurses were addressed by Matron Dot Paschke of the 2/10th AGH and Matron Drummond, who together set out a plan to be followed should the ship be attacked. The nurses were to attend to passengers first then abandon ship themselves. Since there were not enough places in the Vyner Brooke’s six lifeboats for everybody, those nurses who could swim were to take their chances in the water. They had their lifebelts, and rafts would be deployed too.

Fri 13th

Anchored near an island most of the day food question very grim … on our army rations … having two meals a day of army rations – biscuits, bully beef … still doing their utmost for us. lifeboat drill – if necessary. all civilians to boats first whilst girls can to go overboard & swim others allotted to boats – fingers being kept cross – almost ran into a naval battle much searchlights just reaching over. in shelter … behind an island.

All the while, Japanese air and naval forces had been attacking vessels running the gauntlet from Singapore to Batavia via Bangka Strait, the narrow channel of water that ran between Sumatra and Bangka Island off its southeastern coast. Dozens had already been sunk.

On Saturday morning the Vyner Brooke was strafed by Japanese aircraft. In the afternoon the planes returned.

Sat 14

Beautiful sunny morning, calm sea & anchored very pretty island – peacefulness disturbed as planes flew over & machined gunned boat all took to lower deck as pre arranged but raid all over & much discussion on planes … us or enemy aircraft – took up anchor & steamed along – 2 pm. air raid siren all down to lower deck & flat down – six planes attacking once more bombs hit second third time out of 20 bombs third bomb below water line.

whistle for all on deck to take to boats. Wight, Nourse [Neuss], Cuthbertson several civilians injured –

The Vyner Brooke had been attacked by six heavy Japanese bombers. Three times they passed over, but Captain Borton managed to dodge the falling bombs. During the fourth pass, three bombs struck home. The Vyner Brooke immediately listed to starboard. The three viable lifeboats, all on the starboard side, were lowered and filled with women, children and injured passengers, among them nurses Florence Casson, Beth Cuthbertson, Clarice Halligan, Kath Neuss, Florence Salmon and Joan Wight. Then the order was given to abandon ship. Meanwhile, the engine room staff had thrown pieces of wood into the water, and rafts had slid off the decks. After ten minutes the Vyner Brooke turned over and sank. It was around 15 kilometres from Bangka Island.

Bangka Island

Vivian was among the last to leave the Vyner Brooke. After jumping into the water, she managed to reach one of the lifeboats. Some of the injured nurses were aboard, as was Jimmy Miller. The boat drifted with the current, which gradually pulled it towards Bangka Island.

The lifeboat came ashore at around 10.30 pm, and Vivian helped the injured nurses onto the beach. While still approaching the island, some of those on board had seen a bonfire on the shore, and now Vivian, Jimmy Miller and two others set off to find it.

The small party reached the bonfire and discovered that it had been made by passengers from the first lifeboat to leave the Vyner Brooke – among whom were Matron Drummond and several other nurses, and Bill Sedgeman, the first officer. Vivian and Jimmy returned to their own lifeboat with volunteers, who helped to carry the injured nurses back to the bonfire.

As Saturday night passed, the Vyner Brooke survivors were joined by those from other ships sunk in Bangka Strait. When daylight broke on Sunday 15 February more than 70 people were gathered around the bonfire, of whom 22 were AANS nurses.

That day the survivors learned that Bangka Island had come under Japanese occupation. Lieutenant Sedgeman floated the idea of surrendering to Japanese authorities but agreed to wait until the following morning before deciding. The rest of the day passed uneventfully.

Massacre

Early in the morning of Monday 16 February, another lifeboat and several life rafts came ashore carrying British soldiers and sailors. There were now more than 100 people on the beach, many of whom were injured. It was agreed unanimously to surrender to Japanese authorities, and a deputation left for the nearest large town, Muntok, to negotiate this. A short while later most of the group’s civilian women and children followed behind.

Around mid-morning the deputation returned with perhaps 20 Japanese soldiers. The soldiers separated the survivors into three groups: the officers and NCOs, the servicemen and male civilians, and the AANS nurses and a civilian woman, Mrs Betteridge, who had not gone into Muntok with the women and children but had instead stayed with her injured husband. The Japanese soldiers took the two groups of men around a nearby headland and murdered them, bayoneting and machine-gunning them.

The soldiers returned to the women and ordered them to line up on the beach facing the sea. Even the injured nurses were made to stand up.

The women began to walk into the water, and the soldiers opened fire. Mrs Betteridge and 21 nurses died, but Vivian survived. “I was toward the end of the line,” she later told the Australian Board of Inquiry into War Crimes,

and the bullet that hit me struck me at the waist and just went straight through. The force of the bullet knocked me over into the water where I stayed for a few seconds and then being more or less too frightened to get up again, I stayed lying there and the waves eventually washed me back to the sand where I lay for another 10 minutes. All was quiet and then I got up. The Japanese had all disappeared.

Vivian made her way into the lush hinterland and came across a mortally wounded British survivor of the massacre, Private Cecil Gordon Kinsley. Around 28 February, having decided that surrender to Japanese authorities was the only viable option available to them, Vivian and Private Kinsley arrived at a makeshift Japanese internment camp established at the old public works barracks on the edge of Muntok town, known subsequently as the ‘Coolie Lines’ camp, after the labourers who formerly lived there. Here Vivian was reunited with 31 of her comrades. Twelve more had perished when the Vyner Brooke went down or were subsequently lost at sea.

INTERNMENT

The 32 nurses, together with hundreds of civilian women and children and mainly military men, now began a period of captivity that lasted for three and a half years. During this time, they were moved between half-a-dozen camps on Bangka Island and Sumatra, each more hellish than the last. They were subjected to systematic abuse and random acts of violence. They were slapped, yelled at and made to stand in the sun. They were threatened with starvation and, by the end, nearly did starve. They were denied their rights under the Geneva Convention to be treated as prisoners of war.

There was little news of the outside world, and what did arrive was out of date. In March or April 1943, they received a Christmas message from Prime Minister Curtain, in which he told them to “keep smiling.” Sometimes, a Malayan newspaper was smuggled in. There were only three deliveries of mail, and some of the nurses received not a single letter.

When the nurses were permitted to write home for the first and only time, in March 1943, Vivian wrote to her mother:

Women’s Internment Camp

Palembang. Sumatra.

18.3.43

Dear Mother,

Sorry to cause you so much worry but don’t. I have not and never will regret leaving home. My roving spirit has been somewhat checked. I am very well in fact I’m close on eleven stone I’m sure. I have let my hair grow and am now sporting a nob if you please. We do a little nursing about the camp but the sick cases go to the hospital. We find suntops and shorts the ideal uniform. Have learnt to play contract bridge you should learn to play it is by far the superior game and we have a very keen school of players. How is John my love to him and ask Zelda and Con to tell all friends that I am well and often think of everyone give them all my love. I hope it will be possible to hear from you soon. Many happy returns of last month mum I hope you are well and keep smiling and don’t worry over me. Once again love to all in Melbourne, Perth, Adelaide and Broken Hill.

Lots of love. Viv.

The nurses’ letters did not reach Australia until the end of the year, and in some cases not until early 1944. In the meantime, Eva Bullwinkel had been advised by Australian authorities in late March or early April 1943 that her daughter had been made a prisoner of war.

Discipline and routine kept the nurses going. They formed committees and allocated duties, such as preparing meals, cleaning latrines, carrying water, chopping wood etc. Nevertheless, by the end of 1943 sickness had become so prevalent due to chronic malnourishment that only the very worst cases could be admitted to the camp hospital. Bronchitis, dysentery and dengue fever were common complaints, and tinea was widespread.

In November 1944, nearly three years into their ordeal, Vivian and her comrades were moved back to Muntok on Bangka Island. After some initial optimism, it proved to be the worst camp yet. Lice, scabies and bedbugs spread throughout the huts, and disease became rife. Now at the end of their tether, the internees began to die – including the first four AANS nurses. On 8 February Mina Raymont of the 2/4th CCS died of malaria. On 20 February Rene Singleton of the 2/10th AGH died of beriberi. Blanche Hempsted of the 2/13th AGH died on 19 March and Shirley Gardam of the 2/4th CCS on 4 April.

In the same month that Shirley died, the internees were transported to what would be their final camp, at Belalau rubber plantation, near Lubuklinggau, on Sumatra. It lay deep in the jungle some 250 kilometres west of Palembang. The three-day journey claimed many lives, and when they finally arrived at Belalau, Vivian’s comrades continued to die. Gladys Hughes of the 2/13th AGH died on 31 May, Winnie Davis on 19 July, Dot Freeman on 8 August and Pearl Mittelheuser on 18 August. Winnie, Dot and Pearl had all belonged to the 2/10th AGH. Three days before Pearl’s death, Emperor Hirohito had formally announced Japan’s surrender.

RETURN TO AUSTRALIA

On 16 September, after an extensive search for them, Vivian and her 23 comrades were plucked from the jungles of southern Sumatra and flown to Singapore. They were met at the airport by a gaggle of photographers and war correspondents, who took countless photographs and peppered them with questions, and by Red Cross personnel, who gave them tea and biscuits, soap, and cigarettes. Finally, the nurses climbed into waiting ambulances and were driven to St. Patrick’s School, the former base of the 2/13th AGH and now occupied by the 2/14th AGH. It must have been strange indeed for Vivian and the other 2/13th AGH nurses to return after three-and-a-half years.

The painfully thin women were helped up the steps of St. Patrick’s School by orderlies and, after being given a magnificent reception by the staff, took the exhausted nurses to their rooms, where food and warm baths awaited them. Eventually they were assisted to bed.

Later that night, reports of the nurses’ rescue were wired to Australia, and the following day, 17 September, the story was on the front pages of newspapers all around the country. That same day correspondents and photographers were granted further access to the nurses at St. Patrick’s School and spent an hour with them.

The nurses recuperated at St. Patrick’s School for nearly three weeks. They were visited by a steady stream of ex-prisoners of war, received quantities of mail, and ate exceedingly well. They attended a concert featuring Gracie Fields, and on the night of 2 October gave a sherry party to the staff of the 2/14th AGH.

On 5 October the 24 nurses embarked for Australia on AHS Manunda with 370 other released prisoners of war. When the ship arrived in Fremantle on 18 October the nurses were given a gala reception at 110 Perth Military Hospital in the suburb of Hollywood (now part of Nedlands). The hospital was bedecked with beautiful flowers. The following day the Manunda continued on its way, and on 24 October pulled into Melbourne, where the Victorian, Tasmanian and South Australian nurses disembarked. Vivian was home.

BEARING WITNESS

Vivian was not yet 30 years old when she returned home: two-thirds of her life lay before her. These 55 years were marked by tremendous achievement, yet she became best known for her compelling story of survival – and if ever she had wanted to put her war years behind her, she was never able to. From the time that she and the other 23 nurses stepped out of the Dakota at Singapore airport, to her final years, Vivian was called upon to tell her story over and over again.

On 29 October 1945, less than two weeks after arriving home, Vivian told her story to the Australian Board of Inquiry into War Crimes, led by Sir William Webb. She told it again on a far bigger platform on 20 December 1946, when she entered the witness box at the War Ministry Building in Tokyo, Japan, and testified before the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, informally known as the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal.

By then Vivian had been back on active service for nearly a year. She had returned to duty on 21 January 1946 at 115 Heidelberg Military Hospital in Melbourne and had been appointed temporary captain on 6 May. Granted leave from Heidelberg and temporarily attached to the 2nd Australian War Crimes Section on 15 October, she had sailed from Sydney aboard HMAS Kanimbla for Kure, Japan, arriving on 31 October. After testifying, Vivian remained in Japan until 26 January 1947, when she embarked on the Kanimbla for Sydney, arriving on 8 February.

Vivian’s bravery and resilience was recognised just over a month later when she was awarded the Associate Royal Red Cross on 12 March. Two months later she was awarded the Florence Nightingale Medal – the highest international distinction in the nursing profession, awarded for exceptional courage and devotion to victims of armed conflict or natural disaster, or for exemplary service or a pioneering spirit in the areas of public health or nursing education.

On 19 May 1947 Vivian was transferred to the AMF wing of the Repatriation General Hospital in Heidelberg, as 115 Heidelberg Military Hospital had become known after being taken over by the Department of Repatriation. Four months later, on 30 September, she was discharged from the army. The following day she relinquished the rank of temporary captain and was transferred to the Reserve of Officers at the rank of lieutenant. Her decision to leave was based (at least in part) on a reluctance to be posted to Kure with the British Commonwealth Occupation Force.

Vivian remained at the Repatriation General Hospital until 1961, becoming charge sister and eventually deputy matron. Nevertheless, she was granted extended periods of leave to pursue other endeavours.

War Nurses’ Memorial Centre

On 27 June 1945 a committee met at Melbourne Town Hall to discuss the establishment of a social club for the use of trained nurses. The driving forces behind the committee were Edith Hughes-Jones, matron and owner of Windermere Private Hospital in Prahran, and Colonel Annie Sage. In 1943 Ms. Hughes-Jones and Colonel Sage had helped to establish the Centaur War Nurses Memorial Trust. At its second meeting, on 31 July, the committee discussed the possibility of a public appeal to raise funds for the club, and whether such an appeal would be tax free.

By the time the committee met for a third time on 9 October, the 24 Vyner Brooke survivors had been rescued from Sumatra and the shocking story of the Bangka Island massacre had become well known. It was now proposed that if the social club be established as a memorial to all service nurses who died during the war, a public appeal could be held on a tax-exempt basis. At the fourth meeting, held on 20 November, it was agreed that the appeal should be known as ‘Victoria’s Tribute to the Nurses.’ However, it took two more years of discussion and networking before the committee moved any closer to launching the appeal and realising its object.

At a committee meeting held on 27 August 1947 it was suggested that Vivian Bullwinkel be co-opted onto the committee in order to help with the appeal, and it was recommended that Edith Hughes-Jones contact her to discuss remuneration. A meeting was duly arranged between Ms Hughes-Jones and Colonel Sage on the one hand, and on the other Vivian and her friend and fellow prisoner of war Betty Jeffrey, who had known Edith Hughes-Jones prior to her war service. As it happened, while still prisoners Vivian and Betty had themselves discussed the idea of a ‘living memorial’ to their fallen friends and were amenable to Ms. Hughes-Jones’s and Colonel Sage’s vision of a nurses’ memorial centre.

At the next meeting, held on 26 September 1947, it was recommended that Vivian, accompanied by Betty, visit hospitals across Victoria to organise a statewide ‘Queen of Nurses’ contest, a popular form of fundraising in which hospitals select a nurse to be their candidate for Queen and then form committees to fundraise in her name. The nurse who raises the most money is crowned ‘Queen’ and awarded attractive prizes. The ‘Queen’ contest would be one of several fundraising ventures undertaken by the nurses’ memorial centre committee.

In November 1947 Vivian and Betty set out in Betty’s Austin for the Western District on the first stage of their tour of Victoria and the Riverina region of southern New South Wales. In towns far and wide, the two friends spoke at hospitals, schools and town halls, branches of the RSL and the Country Women’s Association, and at outdoor public meetings. They talked of their experiences in the internment camps, advocated for the establishment of the War Nurses’ Memorial Centre (as the centre had by then been named), and drummed up support for the ‘Queen’ contest. They also visited the families of some of their fallen colleagues. In Albury, for instance, they made a point to see Nellie Calnan, the mother of Sister Nell Calnan, who was lost at sea following the sinking of the Vyner Brooke.

On 6 April 1948, at a ceremony held at Melbourne Town Hall, Nurse Lorna Densham of Williamstown Hospital was crowned ‘Queen of Nursing,’ while Sister Joan Newnham of Maffra District Hospital was crowned ‘Queen of Hospitals’ with fewer than 30 beds. Vivian’s and Betty’s efforts had been wildly successful. The ‘Queen’ contest ended up raising more than £78,000, nearly two-thirds of the £121,000 raised in total by the fundraising committee of the War Nurses’ Memorial Centre.

In April 1949 a mansion at 431 St. Kilda Road in Melbourne named ‘Oban’ was purchased for £22,500, and the following month the War Nurses’ Memorial Centre opened. Betty Jeffrey was named as its first administrator.

A TRIP TO ENGLAND

In September 1950 Vivian travelled to England with Betty, who had taken leave from the War Nurses’ Memorial Centre. In London they took up temporary positions at St. Mary’s Hospital in Paddington and moved into a flat in Kensington. They went on bicycle tours of Britain and visited the Continent. In March 1951 they were invited to an audience with Princess Alice at St. James’s Palace and in May were presented to King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in the Throne Room at Buckingham Palace. They were also received by Her Majesty Queen Mary at her home, Marlborough House. Mary was aware of the War Nurses’ Memorial Centre and wanted to know all about it.

In March 1952 Betty returned to Australia, but Vivian stayed on in London and worked as a nurse receptionist at Australia House. On 6 July 1953, she was a participant in the coronation parade of Queen Elizabeth and two months later returned to Australia on the Oronsay.

The Nurses’ Story Reaches a Wide Audience

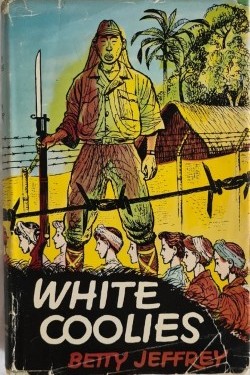

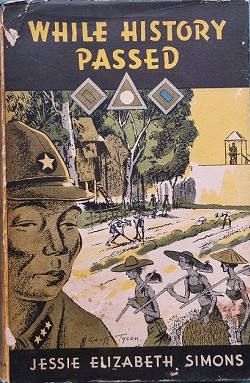

In 1954 the story of the Vyner Brooke nurses’ internment in the camps of Sumatra and Bangka Island reached a much wider audience in Australia with the publication of Betty Jeffrey’s book White Coolies in March and Elizabeth Simons’s book, While History Passed, in May.

White Coolies was based on Betty’s camp diary, written on various scraps of paper and in a notebook and kept hidden for three and a half years. The book was serialised in the newspapers following its publication and turned into an ABC radio serial, which aired in 1955.

While History Passed, written with a good deal of wry humour and pathos, was based on Elizabeth Simons’s recollections. Like White Coolies, it was serialised in newspapers immediately after publication and was republished in 1985 as In Japanese Hands: Australian Nurses as POWS.

In the army again

On 18 November 1955 Vivian returned to the army from the Reserve of Officers, joining the Citizen Military Forces (Southern Command) at the provisional rank of captain (equivalent to the rank of senior sister under the old, non-commissioned system of nursing rank, which was superseded on 23 March 1943). She was attached to 3 Royal Australian Army Nursing Corps (RAANC) Training Unit, where she helped to train part-time women volunteers in nursing duties and army procedures. On 7 December 1955 Vivian’s provisional rank of captain was confirmed and at the same time she was appointed to the rank of temporary major (equivalent to matron).

On 22 December 1961 Vivian was promoted. While confirmed in the provisional rank of major, she was appointed temporary lieutenant colonel (equivalent to principal matron). Two years later, on 8 September 1963, she was appointed lieutenant colonel – her highest substantive rank.

On 31 July 1965 Vivian relinquished the appointment of Commanding Officer, 3rd RAANC Training Unit. She had been with the unit for 10 years and likely became commanding officer on her appointment to temporary lieutenant colonel in 1961 or to lieutenant colonel in 1963.

On 30 December 1970 Vivian retired from the army once and for all. The following day she was placed on the Retired List (Southern Command) and granted the military title of colonel (equivalent to matron-in-chief) with permission to wear the prescribed uniform. She had well and truly earned her stripes.

Kranji War Cemetery and The Singapore Memorial

On the morning of 2 March 1957 Vivian witnessed the official opening of the Kranji War Cemetery and the unveiling of the Singapore Memorial. At the time she was deputy matron at the Repatriation General Hospital, Heidelberg.

Vivian had flown to Singapore with a 15-strong Australian contingent, which also included Lieutenant General Gordon Bennett and Sir Albert Coates OBE, a senior medical officer with the 8th Division who, as a prisoner of war, cared for hundreds of fellow captives on the Burma–Thailand Railway.

Situated on a low hill overlooking the Strait of Johor in the north of Singapore Island, Kranji War Cemetery had begun as a small graveyard attached to a prisoner-of-war camp during the Japanese Occupation. After the Japanese surrender in September 1945, the site was expanded into a permanent war cemetery managed by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. War graves were relocated from prisoner-of-war camps and cemeteries from other parts of the island to Kranji, but due to various factors more than 11 years passed before the cemetery was inaugurated.

On the highest point of Kranji War Cemetery stood Singapore Memorial, the focal point for Vivian, her 14 compatriots and 3,000 other guests, who saw an impressive monument comprising 12 wide columns surmounted by a flat, wing-shaped roof, with a 22-metre pylon, resembling the tail of an aeroplane and capped by a star, rising from its centre.

That morning Governor Robert Black, a former Changi prisoner of war, unveiled the dedication tablet on the Singapore Memorial. Inscribed on the tablet were six simple words: They Died For All Free Men. Then, as a drumroll sounded, draped flags on the 12 columns were pulled away, revealing the engraved names of more than 24,000 Commonwealth service men and women with no known graves. Among the names were those of Vivian’s 21 comrades who died on Bangka Island 15 years earlier and those of her 12 comrades lost at sea. At that time, her eight comrades who died in the internment camps at Muntok and Belalau remained at peace in the jungle clearings where they were originally laid to rest. In December 1961 they were reinterred at the Jakarta War Cemetery in Indonesia.

Following the unveiling and a short speech by Governor Black, the Last Post was played and hymns were sung. Representatives of the Hindu, Muslim, Buddhist and Christian faiths offered prayers. A flypast by RAAF fighter planes and a rendition of God Save the Queen concluded the service, after which the guests laid wreaths and inspected the memorial.

THE 1960s and 70s

At the time of her attendance at the unveiling of the Singapore Memorial, Vivian was deputy matron at the Repatriation General Hospital, Heidelberg. She remained at Heidelberg until sometime in 1961 – at which point, having gained her Diploma in Nursing Administration in 1959, she was appointed matron (later director of nursing) at Fairfield Infectious Diseases Hospital in Melbourne, a position she retained until her retirement in 1977.

Vivian was indefatigable. Aside from her work at Fairfield, and her part-time role with the Citizen Military Forces, she was involved in all manner of charitable organisations, and attended memorial services and prisoner-of-war reunions around Australia.

In 1963 Vivian became involved in the Outward Bound Association. In the same year she was appointed to the Board of Trustees of the Australian War Memorial, serving until 1969. In 1966 Vivian and the other Trustees of the Australian War Memorial met President Lyndon Johnson of the United States.

During this same period, she was acting as Deputy Commander and Nursing Advisor to the Australian Red Cross Society (ARCS). Thirty years later, in March 1992, she was granted honorary life membership of the ARCS.

In 1970 Vivian became a council member of the College of Nursing, Australia. So highly regarded was she that from 1973 to 1974 she was made president of the college.

On 31 March 1971, Vivian was in attendance when the Duke of Edinburgh officially opened newly completed extensions of Australian War Memorial. In August that year she was the guest of honour at the annual RSL Congress in Lae, Territory of Papua and New Guinea.

Between 1972 and 1974 Vivian was a member of the Soroptimists Club, an international organisation concerned with the welfare of women and girls. In April 1975 she became involved in what became known as ‘Operation Babylift,’ the somewhat controversial ‘rescue’ of South Vietnamese babies from orphanages. She travelled to Vietnam with a party of nurses and doctors from Heidelberg and Fairfield Hospitals to manage the transfer of 80 babies and children from Saigon to Bangkok and on to Melbourne. In Melbourne she supervised their convalescence before their adoption to Australian families.

‘This Is Your Life’ and Marriage

The year 1977 was a momentous one for Vivian. Towards the start of the year, she filmed an episode of the popular television program ‘This is Your Life,’ hosted by Roger Climpson. The emotional episode aired on Sunday night 24 April – the night before Anzac Day – and featured guests including Vivian’s POW comrades Jenny Ashton, Veronica Turner (née Clancy), Jess McAuley (née Doyle), Nesta Hoy (née James), Betty Jeffrey, Sylvia McGregor (née Muir), Wilma Young (née Oram), Elizabeth Hookway (née Simons) and Ada ‘Mickey’ Syer; Ken Brown, who helped to locate the 24 nurses in Sumatra at the end of the war and with Fred Madsen flew them from Lahat to Singapore; and Harry Windsor, a medical officer attached to the 2/14th AGH who travelled with the rescue party and met the nurses on Lahat airstrip.

On 16 September 1977, four months after her episode of ‘This Is Your Life’ aired, Vivian married a man that she had first met in the 1960s while staying at the Naval and Military Club in Melbourne – Lieutenant Colonel Francis West Statham, known as Frank. After their marriage at St. Margaret’s Church in Nedlands, Perth, Vivian returned to Melbourne to organise her retirement from Fairfield Hospital, then packed up and moved to Perth to live with Frank.

Vivian did not slow down after her marriage – she was only 61 after all. Between 1980 and 1995 she was chair of the Women’s Auxiliary Group at the Hollywood Repatriation General Hospital – where, when it was known as 110 Perth Military Hospital, the 24 nurses were received on 6 October 1945 after arriving from Singapore on the Manunda. At the same time Vivian travelled relentlessly to the eastern states for various commitments. She was a member and later vice president of the Victorian State Committee of the College of Nursing Australia; a member of the Executive Committee of the Association of Directors of Nursing in Victoria; and Nurses’ Representative on the Nurses’ Wage Board of Victoria.

Back to Bangka

In 1992 Vivian travelled to Bangka Island for the first time since the war. She had gone to choose an appropriate site in the vicinity of Radji Beach for a memorial to her fallen colleagues. On 2 March 1993, in the company of her POW comrades Jean Ashton, Flo Syer (née Trotter), Pat Darling (née Gunther), Mavis Allgrove (née Hannah), Wilma Young and Joyce Tweddell, Vivian returned to Bangka Island for the dedication of the memorial. It was the culmination of a long-standing ambition of Vivian’s to make a fitting tribute to those who did not return. Vivian and her old friends felt that with the formal dedication of the memorial, an unfinished chapter had been properly concluded. “It has always worried me,” said Vivian, quoted in Vetaffairs in March 1993, “that the girls were just … out there. Now they have come home, they belong somewhere.” The seven women then travelled to Jakarta to pay tribute to their eight comrades who died in the Muntok and Belalau internment camps and in December 1961 were reinterred in the Jakarta War Cemetery.

Just over a month before travelling to Indonesia for the dedication of the memorial, on 26 January 1993, Vivian was appointed to the Order of Australia (AO) – a mark of the very great esteem in which she was held by the whole country. Twenty years earlier, on I January 1973, she had been appointed a Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE).

The end of an extraordinary life

Frank Statham died on 3 December 1999 in Claremont. Exactly seven months later, on 3 July 2000, Vivian died of a heart attack at home in Nedlands. She was 84. She was given a state funeral at St. George’s Anglican Cathedral in Perth and was buried alongside Frank at Karrakatta Cemetery. She had lived a most extraordinary life.

Since her death, Vivian has been memorialised and commemorated all around Australia. In 2019 a sculpture of Vivian was commissioned by the Australian War Memorial in partnership with the Australian College of Nursing. The sculpture was created by Charles Robb and unveiled on 2 August 2023. It was the first and remains the only sculpture of an individual woman in the grounds of the Australian War Memorial.

In memory of Lieutenant Colonel Vivian Bullwinkel Statham AO MBE ARRC ED.

SOURCES

- Ancestry.

- Arthurson, L., ‘The Story of the 13th Australian General Hospital, 8th Division AIF, Malaya,’ reproduced by Peter Winstanley on the website Prisoners of War of the Japanese 1942–1945.

- Australian War Memorial, Australian Board of Inquiry into War Crimes, testimony of Vivian Bullwinkel, 29 Oct 1945.

- Australian War Memorial, Diary of Vivian Bullwinkel (Feb 1942), AWM2020.22.49.

- Australian War Memorial, Guide to the Papers of Vivian Bullwinkel 1916–1998, collection number PR01216.

- Burgess, C. (2023), Sisters in Captivity: Sister Betty Jeffrey OAM and the courageous story of Australian Army nurses in Sumatra, 1942–1945, Simon & Schuster.

- City of Prospect, ‘Your Prospect’ (Autumn 1923), ‘From Prospect to Prisoner of War: Vivian Bullwinkel’s Incredible Tale of Survival.’

- Grehan, M. (2016), ‘Queen of the Nurses Quest,’ John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

- International Committee of the Red Cross, ‘Florence Nightingale Medal: Honoring Exceptional Nurses and Nursing Aides – 2025 Recipients.’

- Jeffrey, B. (1954), White Coolies, Angus & Robertson Publishers.

- Kieza, G. (2024), Sister Viv, HarperCollins Publishers Australia (Kindle Edition).

- Loo, J. (2022), BiblioAsia (Jul–Sept 2022), ‘They Died for All Free Men: Stories from Kranji War Cemetery,’ National Library Singapore.

- Manners, N. G. (1999), Bullwinkel, Hesperian Press.

- National Archives of Australia.

- Nelson, H. (2007), ‘Australian Prisoners of War 1941–1945,’ Anzac Portal, Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Australian Government.

- Shaw, I. W. (2010), On Radji Beach, Pan Macmillan Australia.

- Simons, J. E. (1956), While History Passed, William Heinemann Ltd.

- Tsakonas, A. (2018), BiblioAsia (Oct–Dec 2018), ‘In Honour of War Heroes: The Legacy of Colin St Clair Oakes,’ National Library Singapore.

- Walker, A. S. (1962), Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 5 – Medical, Vol. II – Middle East and Far East, Part II, Chap. 27 – Other Prison Camps in the Far East (pp. 645–63), Australian War Memorial.

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS and Gazettes

- The Argus (Melbourne, 7 Apr 1948, p. 3), ‘Nurses Raise £78,302.’

- The Australian Women’s Weekly (28 Mar 1942, p. 7), ‘Home Again – A.I.F. Nurses from Malaya.’

- The Australian Women’s Weekly (27 Feb 1957, p. 21), ‘Singapore Memorial.’

- The Australian Women’s Weekly (9 Nov 1977), ‘Quiet wedding for a famous nurse.’

- Barrier Miner (Broken Hill, 18 Feb 1932, p. 3), ‘High School Prefects.’

- Barrier Miner (Broken Hill, 14 Feb 1933, p. 3), ‘High School Prefects.’

- Barrier Miner (Broken Hill, 16 Jan 1934, p. 4), ‘The Leaving Certificate.’

- Barrier Miner (Broken Hill, 19 Sept 1934, p. 1), ‘Collapsed in Taxi.’

- Border Morning Mail (Albury, NSW, 22 Jan 1948, p. 2), ‘When Singapore Fell.’

- The Canberra Times (12 Dec 1961, p. 10), ‘War Dead Reburial.’

- Commonwealth of Australia Gazette (26 Jan 1956 (Issue No.5), p. 295), ‘Australian Military Forces.’

- Commonwealth of Australia Gazette (22 Feb 1962 (Issue No.11) p. 655), ‘Australian Military Forces.’

- Commonwealth of Australia Gazette (17 Oct 1963 (Issue No.84), p. 3633), ‘Australian Military Forces.’

- Commonwealth of Australia Gazette (2 Sept 1965 (Issue No.72), p. 3837), ‘Australian Military Forces.’

- Commonwealth of Australia Gazette (15 Jul 1971 (Issue No.70), p. 4646), ‘Australian Military Forces.’

- News (Adelaide, 31 Mar 1930, p. 9), ‘Death of Mr. W. Shegog.’

- News (Adelaide, 28 Aug 1953, p. 17), ‘Book News.’

- Royal Australian Navy News (24 Jul 2000, p. 7), ‘Vivian: a Heroine Is Dead.’

- Transcontinental (Port Augusta, 25 Jun 1920, p. 3), ‘Personal.’

- Vetaffairs (Mar 1993, p. 3), ‘Nurses Return to Bangka Island.’