AANS │ Sister │ Second World War │ Malaya │ 2/13th Australian General Hospital

FAMILY BACKGROUND

Louvima Mary Isabella Bates, known as Vima, was born on 1 Jan 1910 in Fremantle, Western Australia. She was the daughter of Mary Jane Wilson (1877–1954) from Millicent, South Australia and Anthony Edward Bates (1875–1947) from County Durham, England.

Mary Wilson was one of 12 children born to Mary Smith (1847–1941) from Adelaide and Samuel Oliver Wilson (originally Nilsson) (1823–1896), a ship’s carpenter from Norway. When Samuel was killed in a railway accident in 1896, Mary senior moved to Fremantle with the children and trained in midwifery. On 8 November 1911, at the age of 64, she became one of the first maternity nurses to be registered in the state.

Anthony Bates was the second eldest of around 11 children born to Sarah Isabella Bramwell (1850–1920), known as Isabella, and Robert Scott Bates (c. 1846–1914). After Isabella’s and Robert’s first child, John William, died in 1875, they migrated with Anthony and his baby brother Robert from northern England to New South Wales on the Peterborough. The ship departed London on 19 October 1877 and arrived in Sydney on 15 January 1878. The family initially lived in Newcastle but by 1885 had moved to Allendale in central Victoria. By 1903 they had moved again, south to Ballarat, where Robert senior worked as a miner and Anthony as a grocer. Following Robert’s death in 1909, Isabella began to work as a nurse, and for a time ran a private hospital on Windermere Street.

Nine years earlier Anthony had served in the Second Boer War as a private with the 1,000-strong 5th Victorian Mounted Rifles. He departed Melbourne with the Rifles on 15 February 1901 and arrived home again on 26 April 1902.

Sometime after his return to Ballarat, Anthony relocated to Fremantle and by 1909 was living on Little Howard Street and working as a warder at Fremantle Prison. His path crossed with Mary’s, and they were married in West Perth in 1909.

Vima was born the following year. She was almost certainly named after (Alexandra) Louvima Elizabeth Knollys, daughter of Ardyn Mary Tyrwhitt and Francis Knollys, who was secretary to King Edward VII for 40 years. ‘Louvima’ was a composite of the first letters of the names of Edward’s three daughters, Louise, Victoria and Maud. Louvima Knollys was 21 years old when Vima was born and had been much in the celebrity columns of the newspapers.

On 3 August 1912 Vima’s younger brother, Kenneth William Edward, known as Ken, was born.

While still working as a warder, on 10 May 1915 Anthony enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) and was attached to the 7th Reinforcements, 16th Infantry Battalion. However, his name does not appear on a nominal roll, and he has no record of service attached to his enlistment papers. It seems, therefore, that he did not move beyond training. He was, after all, nearly 40 years old when he enlisted.

Vima’s maternal uncle Alexander Gilbert Wilson also enlisted in the AIF. He served in France and Belgium and was killed in action on 12 October 1917 at Zonnebeke in Belgium during the Battle of Polygon Wood. His brother William served in France with the 44th Infantry Battalion. He was injured but returned home safely.

NURSING

We know nothing about Vima’s childhood or schooling but can surmise that she attended a state school. We do know that she was a member of the Fremantle Church of Christ, although this may have amounted to simple attendance.

As a young adult Vima decided to become a nurse, inspired perhaps by her grandmothers – one of whom, Mary Wilson, was still alive – and by 1931 had begun training at the Fremantle Hospital on Alma Street. At the time, her parents were living close by at 85 Holdsworth Street, around the corner from Fremantle Prison. They later moved to 8 The Terrace, situated directly outside the prison.

After completing her training Vima became registered in general nursing on 27 November 1934. Sometime later she travelled to Melbourne to undertake midwifery training at the Queen Victoria Hospital and on 10 July 1936 gained her Victorian midwifes’ registration.

Vima returned to Western Australia and on 9 February 1937 gained her state registration in midwifery. In April she took charge of the Infant Health Centre in Kalgoorlie, the main town in Western Australia’s Goldfields region. For at least part of her time in the town, Vima shared a flat at Maritana House with Miss Jo Weston.

In early October 1938, after 18 months in Kalgoorlie, Vima returned to Perth to take up an appointment as tutor sister at Perth Public Hospital. Before leaving Kalgoorlie, she was guest of honour at a farewell party hosted by Mrs E. E. Brisbane and at another one hosted by her colleague Sister M. O’Loughlin.

Meanwhile, Vima’s brother, Ken, had been living in New Zealand and having a difficult time. After arriving in the country in March 1938 as a member of a ship’s crew, he fell on hard times and turned to crime. He committed a series of burglaries and in November 1938 was sentenced to two years’ hard labour. Upon his release he burgled again and in November 1940 was sentenced to a further two years of hard labour. In 1942 he married Lillian Muriel Wareham (née Hulme) and in 1943 enlisted in the Second New Zealand Expeditionary Force, serving until 1945. By 1949 he appears to have returned to Western Australia. For a time, he was living at 190 Douglas Avenue in South Perth, his mother’s address (Anthony Bates had died by then), and working as a clerk. He then appears to have moved to Hazelvale, near Albany, where he worked as a seaman. He died in Queensland in 1963.

ENLISTMENT

When Australia entered the Second World War on 3 September 1939, thousands of Australian men enlisted in the Citizen Military Forces (CMF) for home defence service and in the Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF) for service abroad. Hundreds of Australian women joined the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS).

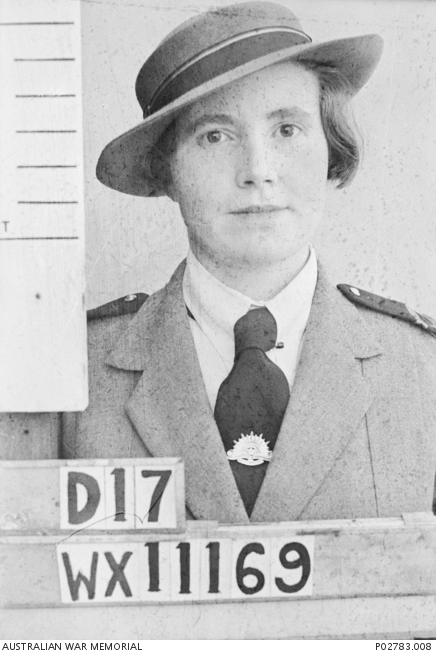

Vima was one of them. On 21 November 1940 she attended Swan Barracks in Perth, attested for both the CMF and the 2nd AIF and underwent a medical. Then she waited to be called up.

Eight months later, on 7 July 1941, Vima was called up for full-time duty with the CMF and posted to the 110th Australian General Hospital (AGH) in Claremont at the rank of sister. (In late 1941 the 110th AGH moved to the Perth suburb of Hollywood and in November 1943 became known as 110 Perth Military Hospital.)

On 15 July Vima was transferred to the camp hospital at Northam Army Camp, 80 kilometres northeast of Perth. On 22 July she was sent to relieve at Faversham Convalescent Home in York, 30 kilometres to the south, returning to Northam on 31 July. On 14 August she returned to the 110th AGH and ceased full-time duty with the CMF.

The following day Vima was seconded to the 2nd AIF and attached to a new Australian Army Medical Corps (AAMC) unit, the 2/13th AGH, at the rank of sister.

THE 2/13TH AUSTRALIAN GENERAL HOSPITAL

By late 1940, Australian and British authorities had become concerned about Japan’s presence in French Indochina and its relationship with the Vichy government. Coupled with this was intelligence that cast doubt on the capacity of Commonwealth forces in Malaya to counter a major Japanese assault. In December 1940 Australia agreed to deploy troops to Malaya to work alongside their British and Indian counterparts and in February 1941 the 22nd Brigade, 8th Division – known as ‘Elbow Force’ – arrived in Singapore on the Queen Mary. Accompanying the 6,000-odd troops of Elbow Force were a number of AAMC units, principally the 2/10th AGH, the 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station (CCS) and the 2/9th Field Ambulance.

As the year progressed, anxiety over Japan’s intentions in Southeast Asia continued to grow. Moreover, it became clear that Singapore Island was vulnerable to attack from the north, separated as it was from the Malay Peninsula by only the Johor Strait, in some parts only a kilometre wide. It had hitherto been assumed than any aggressive action would come from the south. In response, a second 8th Division brigade, the 27th, comprising the 2/26th, 2/29th and 2/30th Battalions, was sent to Malaya in July to reinforce the 22nd Brigade. It was at this point that Colonel Alfred P. Derham, Assistant Director of Medical Services, 8th Division, Malaya, urged the deployment of additional medical personnel to bolster the AAMC units already there. Australian military authorities agreed, and on 11 August the 2/13th AGH began to be formed at Caulfield Racecourse in Melbourne.

Vima knew little of this. She knew of course that she had been chosen for service abroad but did not know where and did not know when. In the meantime, she remained at the 110th AGH. However, by the time she went on pre-embarkation leave between 25 and 31 August, Vima was aware that she would soon depart.

On 6 September Vima and six other AANS 2/13th AGH recruits – Sister Eloise Bales and Staff Nurses Sara Baldwin-Wiseman, Alma Beard, Iole Harper, Minnie Hodgson and Gertrude McManus, all of whom had worked at the 110th AGH with Vima – were guests of honour at a morning tea arranged by the Sportsmen’s Organising Council for Patriotic Funds and held at the Hotel Adelphi. Lieutenant-Governor Sir James Mitchell presented each nurse with an initialled travelling rug to mark her impending embarkation. Five other AANS nurses were also present, all staff nurses – Frances Aldom, Betty Brooking, Mary Hardwick, Beanie Keamy and Gwen Martin. They were due to embark for the Middle East but had already been presented with travelling rugs. Present also was Matron Margaret Edis, Principal Matron (Western Command), who thanked the Sportsmen’s Council for arranging the function.

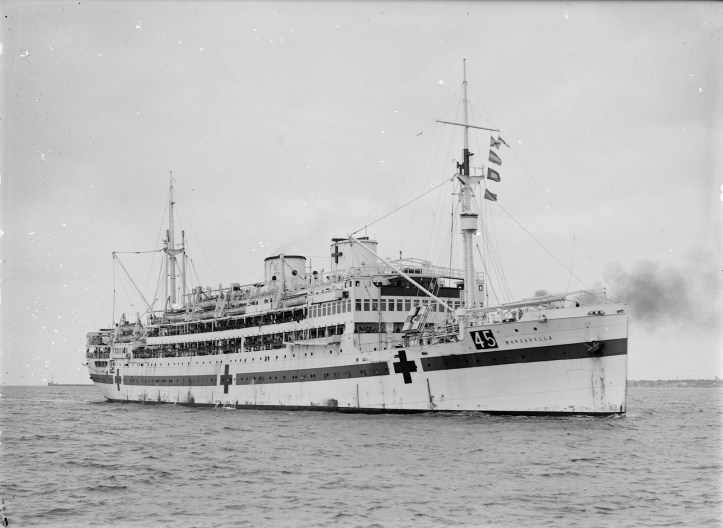

THE WANGANELLA

On Monday 8 September 1941 Vima, Sister Eloise Bales, and Staff Nurses Sara Baldwin-Wiseman, Alma Beard, Iole Harper, Minnie Hodgson and Gertrude McManus travelled to Fremantle and boarded the 2/2nd Australian Hospital Ship Wanganella, which had arrived that day.

Formerly a passenger liner plying the route between Australia and New Zealand, the Wanganella had been refitted in May that year and recommissioned in July. Now on its maiden voyage as a hospital ship, the Wanganella had departed Sydney on 29 August with 21 Queensland and New South Wales 2/13th AGH nurses on board, as well as other staff of the unit. The main body of 2/13th AGH staff then boarded the ship in Melbourne. Aside from around 180 officers and other ranks, there were 25 Victorian, South Australian and Tasmanian AANS nurses and three masseuses (physiotherapists), all of whom were under the temporary charge of Sister Kath Kinsella. Sister Julia Powell from Queensland was second in charge for the voyage, with Eloise Bales and Vima respectively third and fourth most senior.

Staff Nurse Dorothy Atkinson from New South Wales disembarked in Fremantle due to illness and later returned to New South Wales.

As Monday became Tuesday the Wanganella was still tied up at harbour. Vima’s colleague Minnie Hodgson was becoming restless and penned a letter to her friend Norma (an image of which appears in Dietsch):

We’ve been sitting here for two days waiting to be taken off onto the boats & it’s becoming somewhat tedious, we’ve been packed and locked for two days. Yesterday it was too rough & today I think we really will go, they say to Singapore, Malaya, Darwin, Bombay & other places so heaven knows where we’ll go. I don’t care much as long as we get it over.

When the Wanganella finally sailed out of Fremantle’s inner harbour later that day, sailing past the Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth, which were carrying troops to Bombay for transshipment to the Middle East, those on board were officially told by Major Arthur Robinson Home, the 2/13th AGH registrar, that they were bound for Singapore. Some were disappointed; they had assumed that they were going to the Middle East and feared that they would not see action in the East. They could not have been more mistaken.

During the voyage, Vima and the other nurses spent their time demonstrating bandaging and other basic nursing procedures to the unit’s orderlies. They attended lectures on tropical medicine and ran their own sick bay on a roster system. For half an hour each morning they practised using their gas masks and tin helmets. They played quoits on deck and enjoyed other entertainments on board.

SINGAPORE

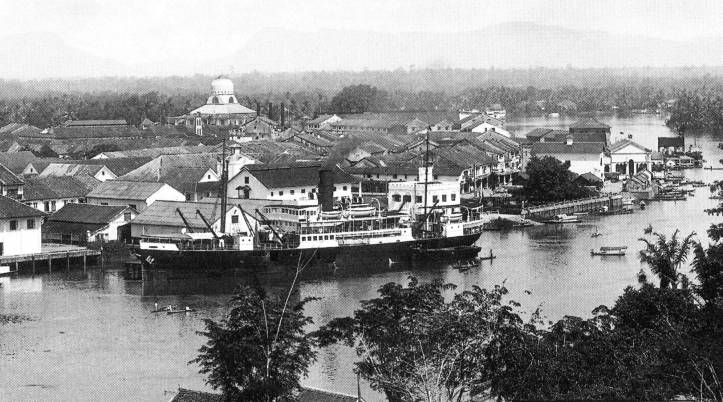

The voyage from Fremantle only took a week. On 15 September, a day after crossing the equator – with the requisite appearance of King Neptune – the Wanganella arrived at Keppel Harbour on Singapore Island and berthed at Victoria Dock.

Ten of the nurses – Staff Nurses Harley Brewer, Joyce Bridge, Vivian Bullwinkel, Veronica Clancy, Trixie Glover, Mollie Gunton, Nancy Harris, Jenny Kerr, May Rayner and Mona Tait – were immediately detached to the 2/10th AGH and stayed on the ship while the others disembarked. They later entrained for Malacca on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula, where the 2/10th AGH was based, and for three weeks learned tropical nursing from their experienced 2/10th AGH peers – who had, after all, been in Malaya since February.

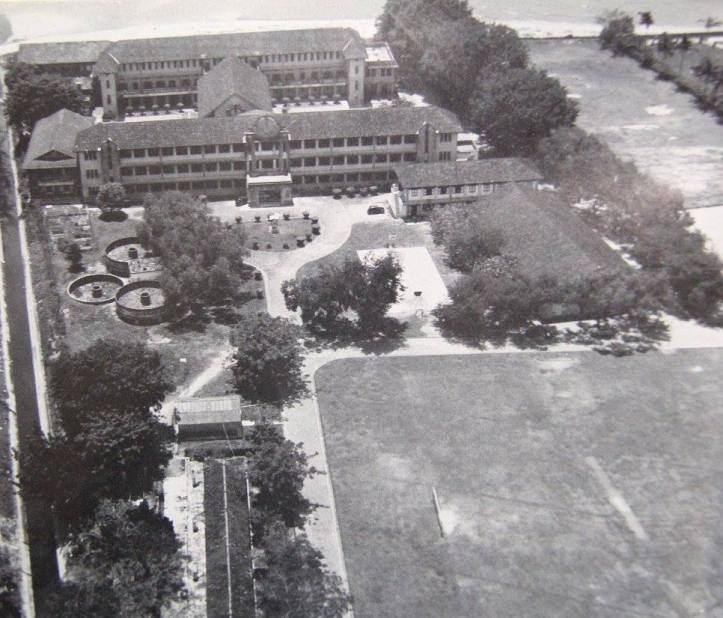

Meanwhile, after disembarking, Vima and the other 43 nurses, the three masseuses, and the male members of staff were met by Colonel Wilfrid Kent-Hughes, Assistant Adjutant and Quartermaster General, 8th Division. Colonel Kent-Hughes had organised buses to transport the staff to St. Patrick’s School, 10 kilometres to the east of Keppel Harbour in the coastal suburb of Katong. Here they were to be billeted until such time as their permanent base – the Tampoi Mental Hospital at Tampoi, on the outskirts of Johor Bahru in the south of the Malay Peninsula – could be made ready. Urgent additions were needed to make the hospital functional, but they would not be carried out for some time.

Late in the day, in sweltering heat, the staff arrived at St. Patrick’s School. The school consisted of three large buildings, two of which were of brick, and many smaller outbuildings. The extensive grounds, 15 acres in area, contained lawns, trees and attractive flowering shrubs, including hibiscus, frangipani, bouvardia and gardenia. The school’s southern boundary was situated on Singapore Strait but separated from the beach by barbed wire, landmines and notices that read ‘Danger – Keep Away.’ The nurses were allocated pleasant quarters in the south wing of the school with wide balconies and views over the forbidden beach. They slept on rope mattresses under mosquito nets, and it took some time to grow accustomed to the heat and humidity.

LECTURES AND OTHER DIVERSIONS

There was little or no substantive nursing work for Vima and her colleagues to do at St. Patrick’s. Instead, they attended lectures on tropical diseases and other relevant topics and were taken on field trips to Singapore hospitals. They visited the British Military Hospital (also known as Alexandra Hospital) to learn about malaria; the Tan Tock Seng Hospital, where clinics were conducted by Prof. Gordon Arthur Ransome and by a certain Dr. Wallace on Friday afternoons; and to Singapore General Hospital to see beriberi and typhoid patients. They also lectured the unit’s orderlies in general nursing. On many afternoons the nurses were free to play tennis or squash, and sometimes at sunset they would walk down the road a little way to watch a ‘changing of the guard’ ceremony at the camp of the 2/26th Battalion. They also began to frequent the fashionable Singapore Swimming Club, located in Tanjong Rhu, halfway between Keppel Harbour and St. Patrick’s School.

For some of the nurses, Singapore was something of a shock to the system. The sights, sounds, smells and customs were all unfamiliar; some of the nurses thought, for instance, that locals who chewed and spat out betel nut had tuberculosis and were therefore to be avoided. Other nurses were challenged by the practice of bartering. However, they soon learned, and shopping became a most enjoyable exercise. Those nurses who began by exploring on foot soon learned that they were expected to catch taxis, in the manner of well-heeled Singaporeans and British expats.

Those well-heeled Singaporeans and British expats were most hospitable towards the nurses. Many opened their fine homes to them and entertained them royally. They were taken on sightseeing tours and invited to dinners, dances and parties. Staff Nurses Phyl Pugh and Margaret Selwood, for instance, found themselves invited to government dinners at Raffles Hotel – very formal affairs, with glamourous people, magnificent décor, an abundance of tropical flowers, and music courtesy of the 2nd Argyll and Sutherland Highlander Regiment band.

The nurses were permitted to go out three nights a week but had to be in by 11.59 pm. The commanding officer of the 2/13th AGH, Colonel Douglas Clelland Pigdon, punished breaches of this rule by confining the whole nursing staff to barracks for a fortnight. According to Phyl Pugh, this was most effective, and the nurses did not break the rules.

COMINGS AND GOINGS

On 19 September Matron Irene Drummond arrived from the 2/4th CCS to take charge of the 2/13th AGH nurses, while Sister Kath Kinsella moved to the 2/4th CCS to take charge of that unit’s eight AANS nurses. The 2/4th CCS had just relocated to a wing of the Tampoi Mental Hospital (the same hospital earmarked for the use of the 2/13th AGH) and had established its own small hospital there.

On 6 October, three weeks after they were detached to the 2/10th AGH, the “mobile 10” – so named by Mollie Gunton – returned to St. Patrick’s. They had gained valuable experience in treating such tropical maladies as tinea, ‘Singapore’ ear, dengue fever, malaria and ulcers, and were now able to pass on their learning to the 2/13th AGH orderlies and stretcher bearers, most of whom already had some experience in bandaging and nursing. The same day the next contingent of 2/13th AGH nurses was sent to the 2/10th AGH, among them Vima’s fellow Western Australians Sara Baldwin-Wiseman, Minnie Hodgson and Gertrude McManus. Then on 14 October eight 2/13th AGH nurses were detached to the 2/4th CCS at Tampoi.

Vima herself was attached to the 2/10th AGH from 23 October to 12 November. The 2/10th AGH was based in a wing of the Malacca General Hospital in Bukit Palah, around three kilometres north of the old Portuguese town. The rest of the modern hospital, which was established in 1934 and was comparable to Australian hospitals, remained a working civilian hospital staffed by expat and local staff, including British nurses. With thousands of 8th Division troops camped within a 100-kilometre radius of Malacca, there was no shortage of work for the nurses of the 2/10th AGH – and for those of the 2/13th AGH on detachment, like Vima. They were kept busy treating tropical maladies and accidental injuries and assisting at routine operations.

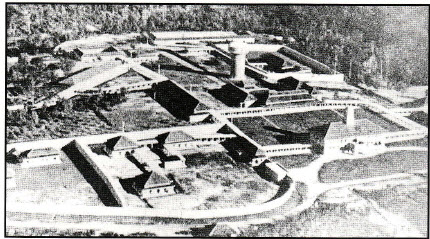

On 20 November, eight days after Vima’s return from Malacca, two AANS reinforcements arrived at St. Patrick’s School, Staff Nurses Margaret Anderson and Vera Torney. They had disembarked that day from the Zealandia with other 8th Division reinforcements, including two AANS nurses for the 2/10th AGH, Staff Nurses Sheila Daley and Jean Floyd. The nurses arrived on the same day that the 2/13th AGH finally received the go-ahead to move into the Tampoi Mental Hospital. Between Friday morning 21 November and Sunday night 23 November, the staff of the 2/13th AGH relocated 100 tons of equipment from Katong to Tampoi in an impressive feat of logistics. The 2/4th CCS, meanwhile, had moved 80 kilometres to the north to Kluang aerodrome.

The Tampoi Mental Hospital had been leased from the Sultan of Johor, with the patients permitted to remain on site in their own section. The sprawling, single-story complex, built in 1939, was ringed by a high wall, sections of which had been torn down by 8th Division soldiers to provide the nurses with escape routes in the event of Japanese attack. Vima’s colleague Sister Elizabeth Simons poked wry fun at the efforts of the Australian soldiers in her book While History Passed (p. 3).

The hospital was not a particularly convenient place to work. Its wards were some distance apart and connected by long, covered concrete walkways, which the nurses sometimes traversed by bicycle, while the nurses’ quarters were at such a distance from the hospital that a kind of small bus had been laid on. On one side of the hospital was jungle, and it was not unusual for scorpions, centipedes and other creatures to wander into the wards. To make matters worse, the hospital was poorly equipped.

It was not all bad, however. Vima’s colleague Mona Wilton appreciated the hospital’s peaceful location, far from the noise of Singapore. “The only noises we have [here] are the wind in the trees and the jungle birds singing to us” she wrote in a letter home (quoted in Angell, p. 43).

PRELUDE TO WAR

By late November, with Japanese troops massing in French Indochina, all the signs pointed to war. On 1 December the codeword ‘Seaview’ was issued, advancing all Commonwealth forces in Malaya to the second degree of readiness. All leave was cancelled and units had to be ready to move at a few hours’ notice to their war stations. On 6 December the codeword ‘Raffles’ was given, indicating advancement to the first degree of readiness. War was imminent.

Despite the official line and widespread belief that Commonwealth forces were sufficiently strong enough to oppose any Japanese invasion, some of the 2/13th AGH officers thought otherwise. Phyl Pugh recalled that one night at tea, soon after the unit had relocated to Tampoi, Major Bruce Hunt told the nurses in unequivocal terms that there would be war with Japan. Japanese forces would invade from the north and advance down the Malay Peninsula. Commonwealth troops would retreat to Singapore Island and be trapped like rats. At the very worst, he said, none would return to Australia. Major Hunt would prove to be correct.

The night of 7 December was calm and peaceful. There was a lovely moon, and all the patients were sleeping. At around 12.30 am on 8 December troops from General Yamashita’s 25th Army made coordinated amphibious landings at Kota Bharu on the northeastern Malaya coast and at Pattani and Singora (Songkhla) in Thailand. At Kota Bharu Indian defenders put up stiff but ultimately futile resistance but the landings in Thailand were unopposed, and soon all three attack groups had established beachheads.

Then, at around 4.30 am, 17 Japanese bombers, flying from southern Indochina, attacked targets on Singapore Island, including air bases at Tengah and Seletar in the north of the island. Raffles Place in Singapore city was also hit, killing 61 people and injuring hundreds, mainly soldiers. Some of the nurses were awakened from their sleep by the drone of aircraft flying overhead, followed by explosions. Some thought that it must be a practice raid. Then they saw tracer bullets followed by ack-ack guns firing skyward at Japanese planes overhead. The realisation struck that this was the real thing: they were at war with Japan.

Elsewhere, Pearl Harbour, Guam, Midway, Wake Island and American installations in the Philippines were attacked and Hong Kong was invaded. Japan declared war on the United States, Great Britain, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa.

JAPANESE INVASION

The Japanese troops soon broke out of their beachheads. From Kota Bharu they began to advance southwards on the eastern side of the peninsula, and from Pattani and Singora they soon crossed into Malaya and moved south along the peninsula’s western side. Backed by mechanized units and devastating air power, the three columns of well-trained, combat-ready Japanese troops forced severely outgunned British and Indian troops to retreat before them. Without air cover, they never had a chance.

On 12 December the 2/13th AGH received a memo from Lieutenant Colonel J. G. Glyn White, Deputy Assistant Director of Medical Services (ADMS), 8th Division, ordering the hospital to expand from 600 to 1,200 beds. By 15 December two new wards had been set up. Staff were also required from then on to wear Red Cross armbands, and the nurses were no longer allowed outside the hospital compound after dark, nor were they allowed visitors.

Vima and her colleagues quickly became used to interrupted sleep, blackouts and air-raid warnings. Some of the nurses were formed into a signals squad, whose job it was to ring a large brass bell upon receiving the message ‘Air Raid Red’ from the Army Signals Corps, whereupon the nurses and their amahs (housemaids) would head for the cover of the jungle. Others formed a decontamination squad.

Christmas came as a welcome distraction. The wards at Tampoi were decorated, and the patients’ rations were boosted for the festive event. The officers helped to carve the poultry and ham and helped the nurses to serve the bed patients. They also made the nurses sit down with the up patients and waited on them. In return the nurses arranged a party in their mess for the officers and on Boxing Day a larger party for the troops.

Events sped up after Christmas. In the face of the relentless Japanese advance, it soon became clear that the 2/10th AGH at Malacca would have to evacuate to Singapore Island, and staff and patients were moved south in stages. Between 29 December 1941 and 5 January 1942, 36 nurses and around 40 other staff joined Vima at Tampoi, bringing scores of patients with them. Twenty more 2/10th AGH nurses were detached to the 2/4th CCS, which had moved from Kluang aerodrome to Mengkibol Estate, a few kilometres outside Kluang.

THE BATTLE OF GEMAS

On 14 January 1942 8th Division troops engaged Japanese forces for the first time. Shortly after 4.00 pm, B Company of the 2/30th Battalion ambushed bicycle-mounted Japanese troops at Gemencheh Bridge, around 120 kilometres north of Kluang. That night Australian casualties began to arrive at the 2/4th CCS at Mengkibol, but thankfully relatively few.

The following day the main force of the 2/30th Battalion, together with elements of the 2/4th Anti-Tank Regiment, made further contact with Japanese troops outside Gemas, 20 kilometres east of Gemencheh Bridge. That evening a convoy arrived at Mengkibol with 36 casualties, and by 6.00 am on 16 January, 165 cases had been admitted and 35 operations carried out. They were then sent on to the 2/13th AGH, and that evening convoys of casualties on stretchers with tickets pinned to them showing the most urgent injuries began to arrive at Tampoi. The admission room quickly established identity, rank and injury, then stretcher bearers ran the wounded to either a ward or an operating theatre. The staff had worked hard to prepare operating theatres to receive them and had by now very nearly fulfilled the 1,200-bed mandate.

Meanwhile, the 2/10th AGH had been busy relocating to Singapore Island. By 15 January Oldham Hall, a Methodist boarding school on Bukit Timah Road, had been requisitioned for use as the unit’s main hospital, while Manor House on nearby Chancery Lane was taken over a day or two later for use as a surgical annexe. Soon the 2/10th AGH nurses detached to the 2/13th AGH and to the 2/4th CCS returned to their unit.

RETREAT TO SINGAPORE

Before long, it was the turn of Vima and her colleagues to retreat to Singapore Island. On 21 January, Lieutenant Colonel Glyn White, in consultation with Colonels Edward Rowden White and Douglas Clelland Pigdon, commanding officers of the 2/10th and 2/13th AGHs respectively, instructed the 2/13th AGH to return to St. Patrick’s School, and a handful of 2/13th AGH nurses and other staff were sent there to prepare it for the unit’s arrival. Abandoned bungalows adjoining the school were cleaned in preparation for use as staff quarters.

The relocation took place over the weekend of 24–25 January. The final convoy, carrying medical patients, arrived at St. Patrick’s School late on Sunday night. Matron Irene Drummond had made sure that beds, pyjamas and towels were ready for them, cold drinks and sandwiches prepared, and teapots warmed up, and by midnight all patients were safely bedded down. The move had been a startling success.

On 28 January the 2/4th CCS followed the two AGHs to Singapore Island, relocating to Bukit Panjang English School. Three days later, on the morning of 31 January, after the last Commonwealth troops had crossed onto the island, British engineers blew the Causeway – the road and rail link between the peninsula and the island – in two places in an attempt to slow the Japanese advance. The first explosion destroyed the lock’s lift-bridge, while the second caused a 21-metre gap in the structure.

That night at approximately 11.00 pm an upper ward on the southeastern corner of St. Patrick’s School sustained considerable damage when a Japanese bomb fell on it. Staff Nurse Gethla Forsyth, who had only just arrived at the 2/13th AGH as a reinforcement staff nurse from Australia – one of six to arrive on the Aquitania – was the first to respond. She quickly assessed the situation and comforted the most agitated of the patients. Miraculously none had been injured, although one had a small glass splinter in his shoulder.

THE LAST DAYS OF SINGAPORE

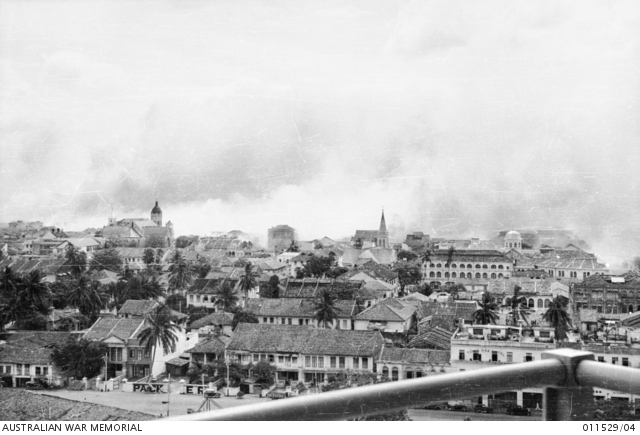

The forces of the Japanese 25th Army were now in complete control of the peninsula, and although the blowing of the Causeway held them at bay temporarily and provided something of a respite for the staff of the 2/13th AGH, St. Patrick’s was anything but peaceful. As Elizabeth Simons noted in While History Passed, “Night and day the [Japanese] planes roared over to attack the harbour, ack ack guns stuttered half the time, sirens wailed and the traditional peace and quietness of a hospital were completely unknown” (Simons, p. 5). Then on 3 February Japanese artillerymen began a ferocious bombardment of Singapore’s oil infrastructure. The resulting fires generated palls of thick black smoke, which hung over the city, creating an eerie twilight. Meanwhile, wealthy residents, mainly European and Eurasian women, children and men, had now fully realised the gravity of the situation and were seeking passage on any vessel that would take them away from Singapore.

In the daylight hours of 8 February, Japanese forces concentrated their artillery on the northwestern defence sector of Singapore Island, destroying military headquarters and communications infrastructure. That night, waves of Japanese soldiers crossed Johor Strait and landed in small boats around the mouth of the Kranji River on the northern coast of the island. They were initially repelled by elements of the 2/20th Battalion and 2/4th Machine Gun Battalion, but the Japanese were too numerous. They eventually overwhelmed the Australians, who could not communicate effectively with their command headquarters due to the damage caused that day, and by the morning of 9 February had established a beachhead. Further to the west there was another landing.

Once again Australian casualties poured into St. Patrick’s, mainly gunshot and shrapnel cases. For the next 24 hours, the hospital’s surgeons and theatre nurses worked nonstop, carrying out 65 operations. Bombing and shelling were now almost continuous, and as the fighting grew closer, the hospital became so overcrowded that casualties lay closely packed on mattresses on floors, in the quartermaster’s store, in the little chapel, and outside on the lawns. Outbuildings and tents were used as wards. The theatre nurses continued to work long hours, and even the ward nurses worked 12-hour shifts. Some of the wounded soldiers begged the nurses to let them leave the hospital to continue fighting. According to Vima’s colleague Staff Nurse Frances Cullen, in an interview with the Australian Women’s Weekly in March 1942, “Even the ones with limb injuries said they could be carried to a gun and could lie beside it to fire it.”

With Singapore’s fate now all but certain, a decision was made to evacuate the Australian nurses.

EVACUATION OF THE NURSES

Early on 25 December 1941 between 150 and 200 soldiers of the Imperial Japanese Army entered a 400-bed emergency military hospital established at St. Stephen’s College in the south of Hong Kong Island and proceeded to massacre as many as 100 patients and medical staff. Among the medical staff were two British nurses from the Bowen Road Military Hospital, six British Voluntary Aid Detachments and five Chinese St John’s Ambulance nurses. They were all wearing nurses’ uniforms and Red Cross armbands. The Chinese nurses and three of the British nurses and VADs were raped and then murdered, while the other four were raped but survived.

Reports of the horrific events soon reached Malaya and began to circulate widely; and as Japan’s march south continued, Colonel Alfred P. Derham, Assistant Director of Medical Services for the 8th Division, began to worry. Between 20 and 25 January 1942 he recommended officially to Major General Gordon Bennett that the Australian nurses should be evacuated from Singapore by the first possible hospital ship. He repeated this recommendation between 25 and 30 January. On each occasion his recommendation was rejected on the grounds that if carried out, it would have had a bad effect on the civilian morale of Singapore. Colonel Derham appealed once again on 8 February 1942, this time directly to Lieutenant General Arthur Percival, General Officer Commanding Malaya, and once again his appeal was refused.

At this point Colonel Derham instructed Lieutenant Colonel Glyn White to send as many nurses as he could with any casualties leaving Singapore, and on the morning of Tuesday 10 February six nurses of the 2/10th AGH embarked on the Wusueh with as many as 350 wounded men, including perhaps 150 Australian 8th Division troops, a few RAAF men, and scores of British and Indian troops. Major General Bennett then stated that the remaining nurses should be embarked as soon as practicable.

At St. Patrick’s, meanwhile, Matron Irene Drummond announced at lunchtime on 10 February that all but 12 of the 2/13th AGH nurses were to go that day as well. However, by the time Colonel Pigdon spoke to the nurses at 4.30 pm, the order had changed, and all were now to remain until late morning the following day.

The next day was Wednesday 11 February. In the morning the 2/13th AGH nurses assembled in the grounds of the hospital and were told by Colonel Pigdon and Matron Drummond that they were to be evacuated later that day. When they gathered again in the afternoon Matron Drummond read from a list the names of 30 nurses who were to leave shortly for the docks in a convoy of ambulances. Among the 30 were Vima’s fellow Western Australians Sara Baldwin-Wiseman, Eloise Bales and Gertrude McManus. Alma Beard, Iole Harper and Minnie Hodgson remained with Vima.

The 30 nurses had no option of either staying with their patients or waiting until such time as all of the nurses could leave together and were told to pack their weekend suitcase and take their respirator, tin helmet and iron rations. With downcast hearts, they were driven to the Adelphi Hotel, just opposite St. Andrew’s Cathedral in Singapore city, where they rendezvoused with 30 nurses from the 2/10th AGH. The 60 nurses were taken on to Keppel Harbour, where they embarked on the Empire Star with as many as 2,400 people – mainly British RAF personnel, but also 140-odd 2nd AIF troops and many civilian refugees, including more than 160 women and 35 children – and, like the nurses on the Wusueh, made their escape to Australia.

Sixty-five AANS nurses remained in Singapore.

ESCAPE ON THE VYNER BROOKE

Late in the afternoon of Thursday 12 February, the 65 nurses were told that they had to go too. Some were furious, others broke down in tears. All were devastated at having to leave their ‘boys.’

At St. Patrick’s, the 27 remaining 2/13th AGH nurses and four 2/4th CCS nurses, who were on detachment, rushed to get ready. They packed a small suitcase, grabbed their tin helmets, respirators and iron rations, and said their hurried goodbyes to their Australian patients, who smiled sadly at them. Then they piled into waiting ambulances and were driven through the ruined city to St. Andrew’s Cathedral – where, during a massive air raid, they rendezvoused with the 30 remaining 2/10th AGH nurses and four 2/4th CCS nurses.

After the air raid the 65 nurses continued to Keppel Harbour. As the ambulances approached the wharves, the way became blocked by abandoned cars, and the nurses got out and walked. They passed through a security gate and in the midst of further air raids proceeded in single file along the wharf towards a tug that would take them out to their ship. As the tug pulled away from the wharf the nurses waved goodbye to Lieutenant Colonel Glyn White.

The 65 nurses were taken out to a small ship, the Vyner Brooke – on which, in a remarkable coincidence, Staff Nurses Vivian Bullwinkel and Nancy Harris had been entertained sometime earlier. On board there were between 200 and 300 people, mostly civilian women, children and old men.

As darkness fell, the Vyner Brooke drew out into Keppel Harbour. As the nurses looked back at the receding waterfront, they saw a mass of flames as oil installations continued to burn – a terrible, unforgettable sight. They retired early to a disturbed night’s sleep, during which there was much shouting and ringing of bells; the next morning, Friday 13 February, they found out that Captain Richard Borton had become lost in the minefield that ringed Keppel Harbour; only the navigation skills of the Vyner Brooke’s first officer, Lieutenant Bill Sedgeman, had got them through.

In order to avoid Japanese spotter planes, for most of Friday Captain Borton kept the Vyner Brooke anchored near one of the many small islands that lined the passage between Singapore and Batavia, the ship’s destination for. In the morning the nurses were addressed by Matron Dot Paschke of the 2/10th AGH, who had overall charge of the nurses, and Matron Drummond. The matrons set out a plan to be followed in the event of attack. The nurses were to help the civilian passengers into the lifeboats and only then abandon ship themselves. Those who could swim were to take their chances in the water; the others were allotted places in the boats. Lifebelts had already been issued, and rafts would be deployed too.

Later on Friday food became a pressing issue. Few of the other people on board had brought food with them, and they felt that the nurses should share their biscuits and bully beef. However, Matron Paschke very firmly said no.

As darkness fell on Friday night, Captain Borton left the cover of the island but sought shelter once again after the Vyner Brooke nearly ran into what the nurses took to be a naval battle. All the while, Japanese air and naval forces had been attacking vessels running the gauntlet from Singapore to Batavia via Bangka Strait, the narrow channel of water that ran between Sumatra and Bangka Island off its southeastern coast. Dozens of ships had already been sunk.

Saturday 14 February arrived, a “beautiful sunny morning,” Vivian Bullwinkel wrote in her diary. The sea was calm and the Vyner Brooke lay at anchor alongside a very pretty island. The peacefulness was abruptly disturbed as planes flew over and strafed the ship. The nurses proceeded to the lower deck and lay flat on their stomachs but by then the raid was over.

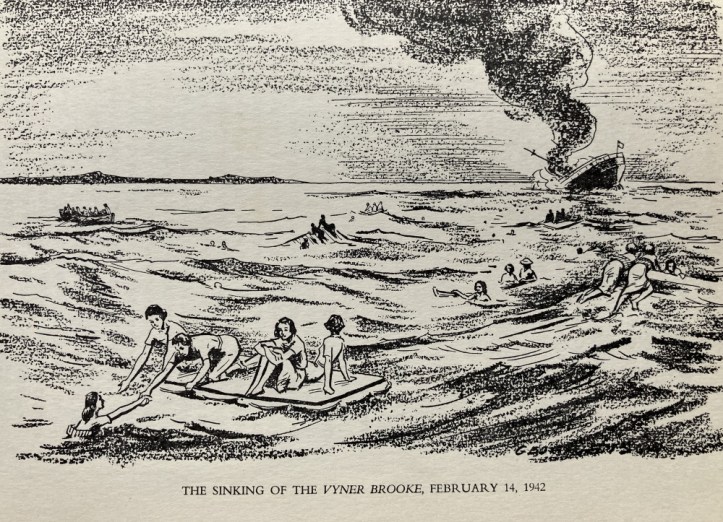

THE SINKING OF THE VYNER BROOKE

Captain Borton then set out again. Just before 2.00 pm he sounded the air raid siren and began evasive manoeuvres. Six heavy Japanese bombers were bearing down on the ship. Once again, the nurses hastened down to the lower deck and threw themselves onto the floor of the lounge, which was under the bridge. Three times the planes flew over, but the Vyner Brooke was zigzagging and the bombs missed. During the fourth pass, however, three bombs struck home. The first destroyed the bridge. The second went clean down the funnel and exploded in the engine room. And as the passengers began to make their way to the upper deck, a third delivered the fatal blow. The Vyner Brooke came to a standstill and began to list to starboard. It was 15 kilometres from Bangka Island.

The nurses carried out the plan agreed upon the previous day. They helped women and children, old men, the wounded, and their own injured colleagues into the three starboard lifeboats, which were then lowered into the sea. One capsized upon entry into the water. Greatcoats and rugs were thrown down to the remaining two, which, although leaking, managed to get away. After a final search of the ship, it was the nurses’ turn to evacuate. They removed their shoes and their tin helmets and entered the water any way they could. Vima was on the upper deck waiting to use one of the rope ladders when she, Iole Harper and Elizabeth Simons decided to use the rope ladder on the lower deck, where there were fewer people. However, upon finding broken glass all over the lower deck, Elizabeth went back upstairs to retrieve her shoes. When she went downstairs again, Vima and Iole had gone. She never saw Vima again.

Elizabeth Simons recounted the sad story in While History Passed (p. 14):

As I stopped to pull off my shoes before joining a rough queue around a rope ladder, I recalled a part of the lower deck which was open and, reasoning that the crush and the distance to the water would both be less, with two other nurses, Sisters I. Harper and L. Bates, I went below decks again. There the floor was covered with ugly-looking broken glass and … I raced back to get my shoes. When I returned, my friends had taken warning from the listing ship and were nowhere to be seen. Sister Harper turned up among the prisoners later on, but Sister Bates was not taken prisoner, we presume she was drowned. Somehow I always expected her to turn up and only abandoned hope … in 1944.

Elizabeth Simons entered the water and pushed off from the side of the Vyner Brooke. After floating in her lifebelt for a while she turned back and watched the ship settle lower in the water – then, “with a rushing gurgle and a burst of spray, slip rapidly out of sight” (Simons, p.16). It had taken less than 20 minutes.

LOST AT SEA

Vima did make it into the water. Staff Nurse Ada ‘Mickey’ Syer of the 2/10th AGH was the last person that we know of to see her alive. While swimming from one little group to another in the gathering darkness of Saturday night, she briefly came across Vima. She described the encounter during an interview conducted in 1989:

We were at water level and so everything’s silhouetted that’s above the water, and there was a head, and there was a voice singing. I called out ‘Who’s that?’ ‘Bates!’ she said. Bates – now Bates was a wonderful young woman. Flaming red hair, bright personality, and she walked into the room and you know vitality walked in with her. ‘Bates!’ she said. In the water swimming around. And I looked around again, I couldn’t see her silhouette and I called out ‘Bates! Bates! Bates!’ but there was no answer. … She wasn’t seen or heard of again.

Vima was one of 12 nurses lost at sea when the Vyner Brooke went down. The other 53 nurses washed up at various places along a section of Bangka Island coastline, 22 of them separated by less than two kilometres. On Monday 16 February they were shot by Japanese soldiers and only Vivian Bullwinkel survived. She joined the remaining 31 nurses in captivity, and in October 1945, 24 returned home.

On 12 June 1944, after Vima was officially listed as missing believed killed, her bereaved parents published the following notice in The West Australian:

Dearly loved and only daughter of Mr and Mrs A. E. Bates, of 190 Douglas Avenue, South Perth; dear sister of Ken (New Zealand Forces). Our Darling Daughter.

Over the next four days, 13 more notices appeared in The West Australian. Such was the regard in which Vima was held.

In memory of Vima.

SOURCES

- Ancestry.

- Angell, B. (2003), A Woman’s War: The Exceptional Life of Wilma Oram Young AM, New Holland Publishers.

- Arthurson, L., ‘The Story of the 13th Australian General Hospital, 8th Division AIF, Malaya’ (edited by Peter Winstanley, 2009).

- Australian War Memorial, Diary of Vivian Bullwinkel (Feb 1942), AWM2020.22.49.

- Australian War Memorial, ‘WX11105 / W102 Ada Corbitt (Mickey) Syer, as a Captain, Australian Army Nursing Service and prisoner of the Japanese, 1941–1945, interviewed by Don Wall’ (1 Dec1989), S04057.

- Crouch, J. (1989), One Life Is Ours: The Story of Ada Joyce Bridge, Nightingale Committee, St. Luke’s Hospital.

- Dietsch, J. (10 Nov 2022), ‘Never-before-seen photos of heroic nurse Minnie Hodgson revealed,’ PerthNow.

- Goossens, R., SS Maritime (website), ‘Wanganella: The History and Story of a Very Special Ship.’

- Henning, P. (2013), Veils and Tin Hats: A history of Tasmanian nurses during the Second World War.

- Jeffrey, B. (1954), White Coolies, Angus & Robertson Publishers.

- Manners, N. G. (1999), Bullwinkel, Hesperian Press.

- Murray, P. L., Official Records of the Australian Military Contingents to the War in South Africa, ‘The Fifth (Mounted Rifles) Contingent’ (pp. 274–303), Australian War Memorial.

- National Archives of Australia.

- Nelson, H. (2007), ‘Australian Prisoners of War 1941–1945,’ Anzac Portal, Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Australian Government.

- Pugh, P. ‘Reminiscences of S/N Phyl Pugh (Mrs. Campbell),’ in Arthurson, L., ‘The Story of the 13th Australian General Hospital, 8th Division AIF, Malaya’ (edited by Peter Winstanley, 2009).

- Royal Collection Trust, ‘Photograph of the Princess of Wales, later Queen Alexandra, attending the Devonshire House Ball, attended by Louvima Knollys, 2 Jul 1897.’

- Shaw, I. W. (2010), On Radji Beach, Pan Macmillan Australia.

- Simons, J. E. (1956), While History Passed, William Heinemann Ltd.

- Tan, E. S. (1964), ‘Characteristics of Patients and Illnesses Seen at Tampoi Mental Hospital (a Preliminary Report).’ The Medical Journal of Malaya, Vol. XIX, No. 1 (Sept 1964), pp. 3–7.

- Wikipedia, ‘Second Australian Imperial Force.’

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS AND GAZETTES

- Auckland Star (Vol. LXIX, Issue 246, 18 Oct 1938, p. 10), ‘Two Accused.’

- Auckland Star (Vol. LXXI, Issue 271, 14 Nov 1940, p. 8), ‘Sentence Day.’

- The Australian Women’s Weekly (21 Feb 1942, p. 7), ‘A.I.F. Nurses Inspired Besieged Singapore.’

- The Australian Women’s Weekly (28 Mar 1942, p. 7), ‘Home Again – A.I.F. Nurses from Malaya.’

- The Ballarat Courier (Vic., 27 Nov 1914, p. 2), ‘Family Notices.’

- The Ballarat Star (Vic., 26 Jun 1902, p. 6), ‘Soldiers’ Certificates.’

- The Ballarat Star (Vic., 17 Jul 1920, p. 2), ‘Obituary.’

- The Border Watch (Mount Gambier, SA, 10 Jun 1896, p. 2), ‘Beachport.’

- The Daily News (Perth, 1 Nov 1910, p. 3), ‘Warder Wise.’

- The Daily News (Perth, 6 Sep 1941, p. 7), ‘AIF Nurses Get Due Praise’.

- Kalgoorlie Miner (WA, 30 Sept 1938, p. 3), ‘A Lady’s Letter.’

- Kalgoorlie Miner (WA, 7 Oct 1938, p. 3), ‘A Lady’s Letter’.

- Kalgoorlie Miner (WA, 16 Jul 1942, p. 2), ‘Army Casualties’.

- Kalgoorlie Miner (WA, 14 Jul 1944, p. 4), ‘Items of News.’

- Kalgoorlie Miner (WA, 28 Apr 1950, p. 2), ‘Nurses’ Hostel Opened’.

- Sunday Times (Perth, 5 Feb 1939, p. 15), ‘The Jottings of a Lady about Town’.

- The Sydney Morning Herald (17 Jan 1878, p. 2), ‘Immigrants per Peterborough.’

- Victoria Government Gazette (3 May 1940), Supplementary Register of Midwives for the Year Ending 31 December 1939.

- The West Australian (Perth, 6 Apr 1937, p. 4), ‘Kalgoorlie Notes.’

- The West Australian (Perth, 11 Jan 1938, p. 4), ‘Kalgoorlie Notes.’

- The West Australian (Perth, 12 Jun 1944, p. 1), ‘Family Notices’.