AANS │ Staff Nurse │ First World War │ No. 6 Australian General Hospital & Woodman’s Point Quarantine Station

FAMILY BACKGROUND

Rosa O’Kane was born on 14 April 1890 in Charters Towers, northern Queensland. She was the daughter of Jeannie Elizabeth O’Kane (1859–1936) and John Gregory O’Kane (1857–1898).

Jeannie O’Kane was born in Ballymoney, County Antrim, Ireland. In May 1878, together with a sister and a brother, she arrived in Australia to join another brother, who had successfully settled years before at Maryborough, Queensland. Jeannie secured an appointment to the Queensland Education Department as a schoolteacher and in 1879 moved from Maryborough to Charters Towers, at the very start of that town’s goldrush, to teach at the Girls’ Central School. Here she met her namesake and future husband, John O’Kane.

John O’Kane was born in Killarney, County Kerry, Ireland. In 1864, when he was seven years old, his father, Timothy Joseph O’Kane, a newspaper editor, left his family and migrated to Melbourne to escape a scandal. He changed his name to Thadeus John O’Kane and by 1874 had moved to Charters Towers and become the proprietor-editor of The Northern Miner newspaper.

On 10 February 1875 John, now nearly 18, and his younger sister Nora departed Queenstown (the port of Cork, now known as Cobh) in Ireland on the ship Naval Brigade and arrived in Townsville on 7 June. Another sister, Mary, appears to have emigrated to Queensland on another ship, and two more sisters died in Ireland. Presumably accompanied by Nora, John moved immediately to Charters Towers and began to work at his father’s newspaper, becoming business manager. He then became editor of the Charters Towers Herald. In 1879, or shortly after, he met a young Irishwoman who shared his surname, Jeannie O’Kane.

Jeannie and John were married on 21 April 1881 in Charters Towers, and together they found happiness and prosperity in the pursuit of journalism. John was still editor of the Charters Towers Herald, and Jeannie assisted her husband in its production. The following year their first child was born, Francis Morris Lewis, followed in 1884 by John Gregory (known as Jack).

The birth of Rosa in April 1890 completed the family. Just one month later, however, the children’s grandfather, Thadeus O’Kane, died after an illness, and what should have been a happy time for the O’Kanes became gloomy. In time John took over the management of The Northern Miner for a new proprietor, but by December 1991 had acquired the Charters Towers Herald and now managed and edited it.

EARLY LIFE

As Rosa – or Rosie as she was often known as a child – grew up, she attended Queenton Kindergarten for some period of time – exactly when and for how long, we do not know. Kindergarten as a concept had only recently been adopted by the Queensland state school system. Records of her further education are elusive. Her brothers appear to have attended Queenton State School, and perhaps Rosie did too.

On Friday 13 September 1895, five-year-old Rosie and her brothers attended a party given by Mrs. Lemel and Mrs. Sullivan in the Australian Natives’ Association Hall. They enjoyed games and dancing until 12 midnight, when a rendition of ‘Auld Land Syne’ brought proceedings to an end. Then on 1 November that year the siblings were among 30 or 40 guests at a party organised by Mrs. Burgess for her nephew, Master Lewis Bromhall. Songs and acting performances kept the children entertained throughout the afternoon.

Tragedy struck again on 22 August 1898, when John O’Kane died of pneumonia in the Charters Towers Hospital after a three-month struggle. Jeannie took over the management of the Charters Towers Herald and for a few years guided it safely through the remaining years of its existence. Tiring of newspaper work, however, and faced with the necessity of providing for her family, around 1902 Jeannie was reappointed by the Education Department and returned to teaching.

GROWING UP

For the next nine years Jeannie moved the family from town to town across successive appointments. In August 1905 she was teaching at Degilbo Provisional School, near Maryborough in southern Queensland, where she stayed until July 1906. She was then transferred to Liontown, a gold and copper mining area around 45 kilometres southwest of Charters Towers. It would appear that here Rosie worked alongside her mother as a pupil-teacher. Rosie also became involved in the women’s section of the Liontown branch of the Political League, acting for a time as secretary.

In June 1907 Rosie and her mother spent a week in Charters Towers to attend the Show, after which Jeannie O’Kane returned to Liontown. Rosie, however, left for Milray Station, a cattle station owned by Arthur Shepherd situated 100 kilometres southwest of Charters Towers. We do not know what position Rosie was taking up at Milray; perhaps it was as governess to the many Shepherd children.

Rosie – or Rosa, since she was by now approaching adulthood – remained at Milray Station until at least September 1908, and every so often visited Charters Towers to stay with friends. Meanwhile, in January 1908 Jeannie had been posted to the Broughton Provisional School, immediately southeast of Charters Towers, and in June 1908 to Kilkivan in southern Queensland. In a touching ceremony she was farewelled on 30 May by the residents of Broughton and presented with a travelling bag and silver mounted purse.

After appointments at Upper Olam, in the Dawson Valley near Rockhampton, and Scotchie Pocket, near Gympie, Jeannie finally returned to Charters Towers in September 1910. She had been appointed as Assistant Teacher at the Girls’ Central School – where she had taught 30 years earlier. Rosie and Jack returned to Charters Towers with her, but Francis was elsewhere.

In January 1913 Rosa was living in Hughenden, 220 kilometres to the west of Charters Towers, and by December 1913 had returned to Charter’s Towers. That month she and her mother spent some time in Townsville staying at Lowth’s Hotel, and Rosa also paid a visit to Mrs and Mr Shepherd at Milray Station.

NURSING TRAINING

By 1914 Rosa had decided to become a nurse and on 24 June that year joined the nursing staff of Townsville General Hospital as a trainee. In January 1916 she gained credits in the practical and theoretical modules of her Invalid Cookery course, part of her nurses’ training but administered by the Townsville Technical College. In 1917 she sat her final examination and achieved the third-highest mark in the state (out of 300 candidates). She was appointed head nurse at Townsville but in October resigned to take up an appointment as matron of the hospital at Winton, a town in the Queensland outback lying 400 kilometres southwest of Charters Towers.

WAR SERVICE

Rosa had begun her nursing training in the year that the Great War had broken out. Now, in 1917, as a certificated nurse, and with the war dragging on, she wanted to serve her country. Despite the fact that she had just been appointed matron at Winton, Rosa applied to join the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS), and in early November was advised by army authorities to be ready to be called up at any time for home service. Sure enough, on 27 November she was appointed to the AANS, 1st Military District (Queensland) and posted to No. 6 Australian General Hospital, at Kangaroo Point in Brisbane. The hospital was housed in a magnificent Italianate building built between 1885 and 1887 and named Yungaba (‘land of the sun’).

In mid-June 1918 Rosa sent a telegram to her mother informing her that she was leaving on transport duty immediately and that she would be unable to get home leave. She followed this with up with another telegram stating that she would not be leaving until 8 July and that she expected to be away for six months.

As things turned out, it was not until some months later that Rosa had the opportunity to serve overseas. On 7 October she enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) and was attached to a unit of AANS reinforcement staff nurses earmarked for service in the military hospitals of Salonika, Greece. The Allies had defeated the Bulgarian forces in northern Greece at the end of September, but many thousands of Allied battle casualties remained in Salonika, and many thousands more required treatment for malaria and other diseases.

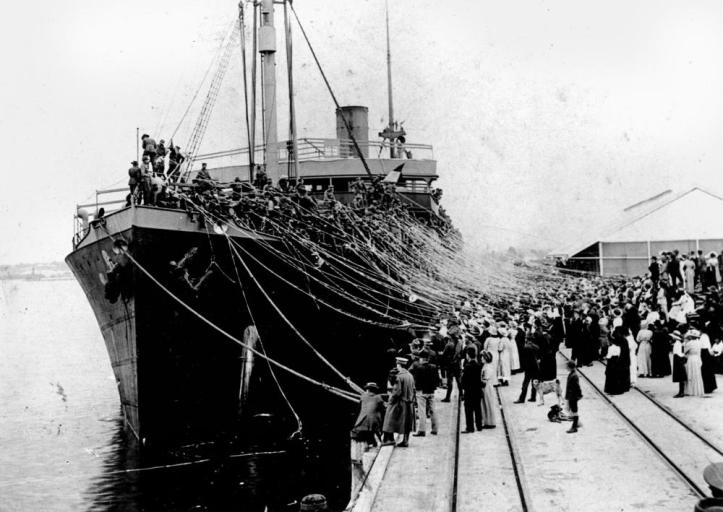

HMAT WYREEMA

Rosa travelled to Sydney and on 14 October she and 36 other AANS reinforcement staff nurses boarded HMAT Wyreema, a coastal steamer requisitioned from northern Queensland. The ship was carrying around 700 AIF reinforcements, who had come from Liverpool Camp, 30 kilometres to the west of central Sydney. After alighting at Central Railway Station, they had marched to Woolloomooloo Bay, from where they were ferried out to the Wyreema. Also on board were nine AANS nurses of No. 8 Sea Transport Section, including Temporary Matron Maude Russell RRC – who assumed charge of the 37 reinforcements – and Staff Nurses Muriel Barnard, Sarah Bell, Elsie Miller and Annie Purcell.

At 4.00 pm the Wyreema drew away from the wharf and anchored off Potts Point, then at midnight set off on its voyage. The ship reached Fremantle on 22 October and entered port at around 4.30 pm. The nurses were granted shore leave and a group of them caught a train to Perth and stayed the night at the Esplanade Hotel.

The Wyreema departed Fremantle on the following day at around 5.00 pm. As it steamed away, boats at anchor in the harbour blew their whistles as their passengers waved flags and cooeed. During the voyage the nurses read, sewed, played cards and games on deck, attended church services, boat and fire drills, dinners and concerts, and even staged a play called ‘Search Me,’ in which Rosa and another nurse acted the part of Bluebeard splendidly.

At around 9.00 am on 8 November the Wyreema arrived at the small bay off the town of Durban, South Africa. Shore leave was forbidden due to an outbreak in the town of pneumonic influenza – the so-called Spanish flu. While at anchor in the harbour the ship was coaled by riggers working alongside on coal lighters, a process that continued into the following day and which covered everything – and everyone – in coal dust. On the morning of 10 November, the ship pulled in alongside the wharf to take on water. Later, a few of the men jumped over the side of the ship and began swimming towards shore. They were brought back at around 5.00 pm, and at 5.30 pm the Wyreema, still covered in coal dust, drew anchor and sailed for Cape Town.

The following day was 11 November. Early that morning, in a clearing in the Forest of Compiègne in northern France, the Armistice that ended the fighting on the Western Front was signed in Marshall Foch’s railway carriage. At 11.00 am the guns fell silent and the Great War was over. News of the Armistice reached Australia later that day. Naturally, it was received with outpourings of joy, but also presented logistical challenges for military authorities: what should be done, for example, with the troopships already en route to Europe?

In the early afternoon of 13 November, two days after the signing, the Wyreema dropped anchor in Table Bay, Cape Town. Once again shore leave was forbidden, as Cape Town was also gripped by influenza, and for days everyone was stuck on board doing the same things they had done during the voyage. On 19 November Rosa’s colleague Susie Cone, from Victoria, who kept a diary, noted that “the government don’t seem to know what to do with us.”

On 20 November some of the nurses and officers from the troopship Borda came across to the Wyreema for lunch. After lunch the visit was reciprocated by some of those on the Wyreema. The Borda had arrived in Table Bay two days earlier from England and was en route to Australia with 1,000 Anzacs on board. Like those on the Wyreema, its passengers had not been allowed shore leave.

At long last those in authority on board received orders, and at 8.30 pm on 23 November the Wyreema steamed out of Table Bay bound for Australia. Staying behind due to personal reasons were four of Rosa’s AANS colleagues, Marguerita Mayor, Maude Rudall, Florence Holden and Cora MacNeil, along with some of the officers and men, and one of the ship’s padres.

As it sailed eastwards through the Indian Ocean, the Wyreema began to pick up radio messages from the troopship Boonah. Like the Wyreema, the Boonah had been on its way to the front and following the Armistice had spent more than a week in Durban before being recalled to Australia. Ominously, pneumonic influenza had broken out on board.

HMAT BOONAH

The Boonah was the last ship to leave Australia with troops for the front. It departed Port Adelaide on 22 October bound for England via Fremantle and South Africa. On board were around 1,000 AIF personnel, including some 30 members of the Australian Army Medical Corps. After leaving Fremantle on 30 October the ship steamed across the Indian Ocean and was three or four days out from Durban when the Armistice was signed.

The Boonah was ordered to continue to Durban. Upon arrival the soldiers discovered that due to the outbreak of influenza they were not permitted shore leave and were forced to remain on board. After spending eight days in Durban harbour awaiting orders, coaling and discharging cargo, the Boonah set out for Fremantle on 25 November. That same day one of the soldiers or crew showed symptoms of influenza. Somehow the virus had been brought on board.

Some reports state that a number of soldiers and crew had disobeyed orders and gone ashore, while other reports suggest that local stevedores had infected crewmembers during the offloading of cargo. Regardless, as the days went by, the virus spread unchecked. Before long most of those on board had either contracted pneumonic influenza or were contacts of someone who had, and all the while the Boonah’s radio operator transmitted details of the daily increasing tally.

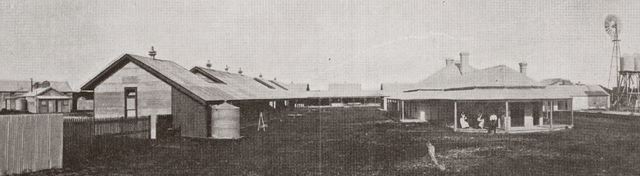

Meanwhile, the Wyreema, running a day ahead of the Boonah, arrived at Fremantle early on the morning of 10 December. While the ship was sitting in the harbour, Lieut. Colonel P. M. McFarlane, officer in charge of the AIF troops on board, received a request to land 20 of the AANS nurses at Woodman’s Point quarantine station, 10 kilometres south of Fremantle’s inner harbour, in anticipation of the arrival of the Boonah.

Woodman’s Point Quarantine Station

Susie Cone, among the 20 to disembark, described the events of that day in her diary (spelling and grammar preserved as written):

Tuesday 10th [December]. Got into the port at Freemantle at daylight. Got up early & when the pilot came off he told us that we could not have shore leave. At about 9.30 AM the shore authorities signalled for 20 sisters to nurse Spanish flue. Matron called for volunteered 26 of us spoke up & then we drew lot’s for places. Brady & I were amongst the 20. We left the old Wyreema at 4 pm on Tuesday & are all feeling very lonely. Sat on the jetty here at Woodmans point while the people at the station finished a row they were having. Arrived up here hungry & tired. Unpacked & had a look around. Brady & I went down onto the jetty & gazed longingly out at the old boat wishing to heaven we were back there again.

Rosa was also among the 20. The others, apart from Susie and ‘Brady’ (possibly Vera Bradshaw from Victoria), were Ethel Newby, Catherine Thomas, Ada Thompson and Mary Walker from New South Wales; Doris Bell, Margaret Bourke, Grace German, Naomi Higman, Jessie Hogg and Jane Robson from Queensland; Grace Collins, Maud Hamilton, Nellie Manning, Stella Morris, Lizzie Scott and Gertrude Wilkinson from Victoria; and Harriet Jackson from South Australia. They all knew perfectly well the risk they were taking but were eager to help.

When the Boonah arrived at Gage Roads, Fremantle’s outer harbour, early on 11 December, there were more than 300 cases of influenza on board. The worst began to be disembarked during the morning and soon arrived at Woodman’s Point. As described by Susie Cone, they were in a bad way.

Wednesday 11th. Got up & then started to get things ready for the boys coming off the Boonah. Wilkinson Hamilton Bradshaw & I were in W 3, a hut holding 8 beds & 10 tents. No conveniences of any kind. About 10 AM the boys began to come up from the jetty. Our tents & hut were soon full Poor lads were in a terrible plight. Filth & dirt all over them terribly sick, we had no drugs, no clean shirts or pyjamas to put on them, all we could do was to wash them & get them as comfortable as possible Three died the first day.

The quarantine centre was totally unprepared for the influx of patients, and conditions for nursing were dire, as Susie Cone makes clear: “Thursday 12th. Boys all very ill. Very little to feed them on. Drugs scarce. This place is Hell.”

By Friday night, more food and drugs were available, but the number of deaths had risen to 10. Rosa had managed to send a telegram to her mother informing her that she had reached Fremantle and was nursing the troops quarantined at Woodman’s Point.

FINAL DAYS

On Saturday Rosa herself came down with influenza. Other nurses were falling ill too, including Sister Leeds, a civilian nurse, one of a number who had volunteered to work alongside the AANS nurses at the quarantine centre.

Rosa’s condition worsened the following day, Sunday 15 December – a “blazing hot day,” wrote Susie Cone, and so different from the previous Sunday: “No church parade, no singsong nothing but dust sand & flies & sickness.”

By Thursday 19 December, the day the nurses moved down to a new hospital, Rosa had relapsed to a dangerously ill condition after appearing to improve earlier in the week. There were at least six other nurses ill by then: Maud Hamilton, Nellie Manning, Ethel Newby, Ada Thompson, Mary Walker and Gertrude Wilkinson.

Realising the gravity of her situation, Rosa prepared for and received the last sacraments from the Rev. Father Flynn of the Order of Mary Immaculate. Father Flynn had been resident at the quarantine station almost from the beginning of the outbreak and had helped a good many ill soldiers.

Rosa died at 1.45 am on Saturday 21 December 1918. In her final hours she had been comforted by Stella Morris, who had also contracted influenza, and nursed by Grace German, who had thus far remained well. Father Flynn was also with her for a time before she died. Susie Cone recorded the tragic event in her diary:

Sat 21st Poor old O’Kane died early this morning, one can hardly realize that she has gone everybody very depressed about it. We gave her a military funeral today at 4 p.m. It’s sad to see how we old Wyreemians have decreased only nine of us on duty now…

Funeral

Stella Morris later sent a poignant letter to her mother, Mary Morris of Ballarat, Victoria, in which she briefly describes Rosa’s funeral. An extract was printed in the Weekly Times on 18 January 1919, as follows:

Between 2 and 3 a.m. on a beautiful moonlight night, four sailors carried the body (wrapped in a winding-sheet of the Union Jack) to the mortuary out in the scrub. I followed, and saw the necessary details executed. Later in the day the burial took place at the Quarantine Station. The nurses made little wreaths from West Australian wild flowers, which were placed on the coffin with the Union Jack. I did not leave the graveside till ‘The Last Post’ was sounded.

Three more nurses died at Woodman’s Point during this dreadful time – Ada Thompson on 1 January 1919, Hilda Williams, one of the civilian nurses, on 4 January, and Staff Nurse Doris Ridgway of the AANS on 6 January. Doris was one of a contingent of 12 South Australian AANS nurses who had arrived on Christmas Eve from No. 7 AGH in Keswick, Adelaide.

As many as 28 soldiers lost their lives at Woodman’s Point.

IN MEMORIAM

In September 1919 the residents of Charters Towers were invited to subscribe to the purchase of a monument to be erected over Rosa’s grave at Woodman’s Point. By April 1920 the subscribers had raised £69 9s, and by February 1921 a granite obelisk had been installed over Rosa’s grave, and Jeannie O’Kane was on her way to Perth on the Orsova to see it for the first time.

Every year, at the time of her daughter’s death, Jeannie placed a notice in the Charters Towers and Townsville newspapers. This one was printed in the Northern Miner on 20 December 1924:

O’KANE. —In honored and revered memory of Sister Rosa O’Kane, Australian Army Nursing Service, only daughter of Mrs. J. E. O’Kane, and sister of Mr. Frank O’Kane and Mr. Jack O’Kane, who died on service at the Quarantine Station Fremantle, W.A., 21st December, 1918.

R.I.P.

Look down ye moon and set not soon,

Look down ye golden stars,

And shed your light, on souls tonight

Who have shed their prison bars

For her dear soul has reached the goal,

The heavenly haven nigh,

She will not weep – though o’er the deep,

Her flag rides half-mast high.

In memory of Rosa.

SOURCES

- Ancestry.

- Australian Dictionary of Biography, ‘Thadeus O’Kane (1820–1890),’ by H. J. Gibbney and June Stoodley (originally printed in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, Vol. 5, 1974).

- Australian War Memorial, Australian Imperial Force Nominal Roll – Nurses (Jul 1915–Nov 1918), AWM8 26/100/1.

- Families and Friends of the First AIF, Australian Nurses of the Great War Database.

- National Archives of Australia.

- Public Record Office Victoria, ‘Diary of Nurse Susie Cone, 1918–1919,’ VPRS 19295.

- Queensland State Archives.

- The Wyreemian: The Magazine of the Ship’s Company of H.M.A.T. Wyreema (7 Nov 1918), National Library of Australia.

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS

- The Brisbane Courier (18 Feb 1865, p. 5), ‘Supreme Court.’

- The Evening Telegraph (Charters Towers, 31 Aug 1910, p. 3), ‘Welcome Back!’

- The Evening Telegraph (Charters Towers, 4 Sept 1919, p. 2), ‘Late Sister O’Kane.’

- The Evening Telegraph (Charters Towers, 7 Feb 1921, p. 2), ‘Sister Rosa O’Kane’s Monument.’

- Gympie Times and Mary River Mining Gazette (13 Jun 1908, p. 3), ‘Personal.’

- Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (21 Aug 1905, p. 3), ‘Hospital Ball At Degilbo.’

- The North Australian (Brisbane, 6 Dec 1864, p. 2), ‘The Late Fire in Queen Street.’

- The Northern Miner (Charters Towers, 19 May 1890, p. 3), ‘The Northern Miner.’

- The Northern Miner (Charters Towers, 23 Aug 1898, p. 3), ‘Death of Mr. J. G. O’Kane.’

- The Northern Miner (Charters Towers, 9 Apr 1907, p. 3), ‘Liontown Notes.’

- The Northern Miner (Charters Towers, 21 Jan 1908, p. 6), ‘Social Items.’

- The Northern Miner (Charters Towers, 9 Jun 1908, p. 3), ‘Social Items.’

- The Northern Miner (Charters Towers, 18 Sept 1908, p. 3), ‘Social Items.’

- The Northern Miner (Charters Towers, 20 Jan 1913, p. 4), ‘Social Items.’

- The Northern Miner (Charters Towers, 26 Jun 1914, p. 7), ‘Social Items.’

- The Northern Miner (Charters Towers, 23 Oct 1917, p. 2), ‘Personal.’

- The Northern Miner (Charters Towers, 10 Nov 1917, p. 5), ‘Social Items.’

- The Northern Miner (Charters Towers, 19 Jun 1918, p. 3), ‘Personal.’

- The Northern Miner (Charters Towers, 27 Jun 1918, p. 2), ‘Personal.’

- The Northern Miner (Charters Towers, 23 Dec 1918, p. 2), ‘Personal.’

- The Northern Miner (Charters Towers, 11 Jan 1919, p. 5), ‘Personal.’

- The Northern Miner (Charters Towers, 20 Dec 1924, p. 4), ‘Roll Of Honor.’

- The Northern Miner (Charters Towers, 7 Jul 1936, p. 2), ‘Obituary Mrs. J. E. O’Kane.’

- The Northern Mining Register (Charters Towers, 24 Dec 1891, p. 51), ‘The Late Mr. Thadeus John O’Kane.’

- The North Queensland Register (Townsville, 18 Sept 1895, p. eight), ‘Children’s Party.’

- Observer (Adelaide, 28 Dec 1918, p. 33), ‘Wyreema Troops Landed.’

- The Queenslander (Brisbane, 16 Nov 1895, p. 918), ‘Northern Social Gossip.’

- The Queenslander (Brisbane, 21 Jul 1906, p. 14), ‘Our Neighbours.’

- Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser (20 May 1890, p. 2), ‘Thadeus O’Kane Dead.’

- The Register (Adelaide, 21 Dec 1918, p. 9), ‘Wyreema Troops Landed.’

- The Sydney Morning Herald (15 Oct 1918, p. 6), ‘For the Front.’

- Townsville Daily Bulletin (22 Jan 1916, p. 5), ‘Technical College Examinations.’

- Townsville Daily Bulletin (18 Dec 1918, p. 4), ‘The Late War.’

- Townsville Daily Bulletin (29 Apr 1920, p. 5), ‘Sister O’Kane’s Memorial Fund.’

- Townsville Daily Bulletin (9 Sept 1931, p. 12), ‘Queenton State School.’

- Townsville Daily Bulletin (22 May 1933, p. 3), ‘Vital Statistics.’

- Townsville Daily Bulletin (7 Jul 1936, p. 6), ‘Personal.’

- Weekly Times (Melbourne, 18 Jan 1919, p. 43), ‘Died at Their Posts.’

- The West Australian (Perth, 22 Jan 1919, p. 6), ‘To the Editor.’