AANS │ Captain │ Second World War │ Malaya │ 2/10th Australian General Hospital

Family background

Kathleen Constance Blake was born on 16 July 1912 in Chatswood, Sydney. Her mother, Catherine Florence (Katie) Hancock (1876–1967), was born in Clunes, central Victoria, and her father, George Blake (1869–1950), was born on Nebea Station in Coonamble, New South Wales, and would later become an accountant.

Catherine and George were married on 14 May 1901, in Ipswich, Queensland. Their first child, Marjorie, was born in 1902, followed by George (known as Don) in 1903 and Arthur in 1905, the latter two in the Townsville area.

The family then moved to ‘Egromont’ in Chatswood, inner northern Sydney, where Winifred (Winnie) was born in 1908, Roland (known as Kevin) in 1910, Kathleen in 1912 and Jean in 1917.

Early Life

Kathleen – or Pat, as she was known – and her sisters attended Abbotsleigh Ladies’ College (also known as Abbotsleigh Church of England School for Girls) at Wahroonga. In 1928, while Pat was working towards her Intermediate Certificate, her sister Winnie married Arthur Kingsford Smith on 22 March at the Sydney Church of England Grammar School Chapel, in North Sydney. Pat was one of four bridesmaids, each of whom wore frocks of peach pink georgette, made with tight bodices and full-frilled skirts and worn with pink aviator caps – possibly in reference to the groom’s famous surname.

Pat was awarded her Intermediate Certificate in February 1929 and completed her schooling that year. She was evidently good at tennis, for at Abbotsleigh’s end-of-year speech and prize day she was awarded the senior doubles prize with her doubles partner, E. Dettman.

For several years Pat remained in contact with Abbotsleigh via the Old Girls’ Union. On 21 May 1930 she helped to organise the school’s annual reunion dance, held at Farmer’s Blaxland Galleries with 300 guests in attendance, while on 18 September 1937 she and her sister Jean took part in the Old Girls’ Union’s annual tennis tournament.

Queen of the Air

In April 1932 Pat was one of 60 women nominated to take part in a ‘Queen of the Air’ competition organised by the Aero Club of New South Wales. The club aimed to meet the growing interest of women in aviation while raising funds for the Benevolent Society of New South Wales. Each nominee was placed in one of 12 groups of five women each and, with the help of a committee, competed within her group to raise the most money for the Benevolent Society by holding fundraising activities. Each group winner would be awarded a place in one of 12 planes competing in the marquee event, the ‘Ladies’ Air Tourney Race’, due to be held at Hargrave Park, at Warwick Farm in southwestern Sydney, on 20 August. The entrant in the winning plane would receive honorary membership of the Aero Club and, more substantially, 12 months’ free flying or a car.

For three months, Pat and her committee held several fundraising events, including a ball at the Killara Soldiers’ Memorial Hall on 1 July, and at the end of July Pat was declared the winner of Group 2. She was duly awarded a seat in the Hermes Moth piloted by Mr. Marni Kerry.

On the day of the race a festive atmosphere pervaded Hargrave Park. Pat and her family had organised an afternoon picnic. Present were her father, her siblings Kevin, Don and Jean, and her friends K. Oakeshott, Peg Williams and Grantley Roberts. At 3.35 pm the race began, and although Marni Kerry flew admirably, his plane did not cross the winning line first. Nevertheless, of the 60 women competing, Pat and her committee had raised the second-highest amount of money for the Benevolent Society, and she was due to be awarded a diamond ring or free flying.

Nursing and Enlistment

In the mid-1930s Pat decided to become a nurse and began her training at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, in Camperdown, south Sydney. In November 1936 she passed her Nurses’ Registration Board examination and became registered on 15 April 1937.

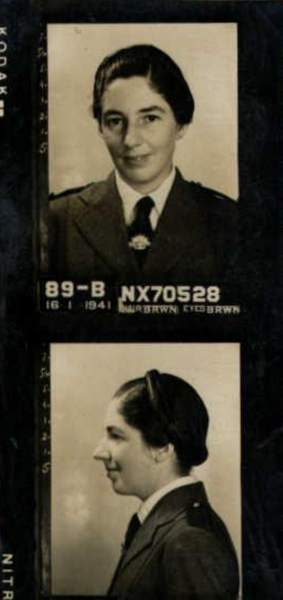

When war broke out in Europe, many Australian women and men volunteered for service – particularly after the German invasion of the Low Countries and France in June 1940. Pat was one of them. She had her medical that very month, June 1940, and on 20 December enlisted in the Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF). She was attached to the Emergency Unit of the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) and posted to the camp dressing station at Greta Camp, in the Hunter Valley, New South Wales.

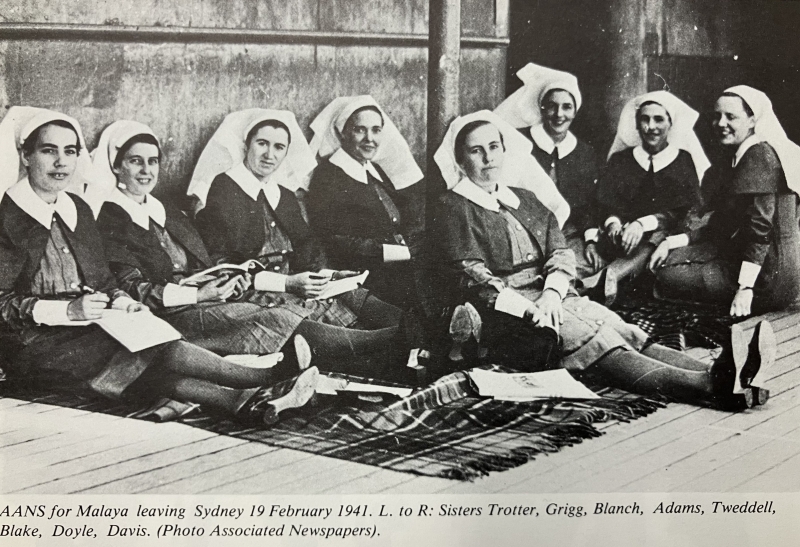

At Greta Camp Pat likely met fellow AANS recruits Winnie May Davis from Ulmarra and Jess Doyle from Potts Point. In January 1941 all three were advised by the Army that they would soon be joining a medical unit for overseas service, and after a period of pre-embarkation leave, on 31 January were attached to the 2/10th Australian General Hospital (AGH). Their destination remained classified.

Queen Mary

On 3 February Pat, Winnie and Jess proceeded to Darling Harbour, where they met fellow New South Wales 2/10th AGH recruits Pat Gunther, Marjorie Schuman, Kath Neuss and others. They were all taken by ferry to the Queen Mary, which was lying at anchor off Bradley’s Point. On board already was a contingent of Queensland nurses, including Joyce Tweddell, Florence Trotter, Jessie Blanch, Pearl Mittelheuser, Chris Oxley and Cecilia Delforce.

By 4 February a total of 43 AANS nurses of the 2/10th AGH had embarked, as well as six nurses attached to the 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station (CCS). The two units were tasked with looking after nearly 6,000 troops of the 8th Division, 2nd AIF, who were sailing to Malaya on the Queen Mary following a British request for Australian reinforcements to join British and Indian troops in garrison duties.

In the early afternoon the mighty ship left Sydney Harbour to the cheers of thousands of spectators. It steamed out through the Heads and joined a convoy of ships heading for Bombay. On 16 February, when the convoy was immediately south of Sunda Strait, the Queen Mary broke away from the convoy and steamed off towards Singapore.

Malaya

Two days later the nurses arrived. They disembarked and boarded a train for Malacca, on the west coast of the Peninsula, where the 2/10th AGH would be based. They arrived early the next morning, immediately went to bed and awoke to find themselves in the Colonial Service Hospital.

For the next 10 months Pat and her colleagues enjoyed life in British Malaya. Their work looking after the troops was routine and not onerous. They had plenty of free time for social and sporting activities and were granted generous periods of leave.

All that changed on 8 December, when Japan launched an invasion of Malaya. Amphibious troops landed at Kota Bharu in the north while Singapore was being bombed in the south. At the same time Pearl Harbour was being attacked and Hong Kong invaded. The Pacific War had begun.

Japanese infantry, backed by mechanized units and substantial sea and air power, surged down the Malay Peninsula and forced the severely outgunned Commonwealth troops to retreat southwards.

Evacuation

In mid-January 1942 the 2/10th AGH was forced to relocate to Singapore Island, and by the end of January all Commonwealth troops and medical units had followed suit. When Japanese forces crossed Johor Strait on the night of 8 February, the end was nigh.

A decision was made to evacuate the Australian nurses. On 10 February, despite their protests, six nurses departed aboard the hospital ship Wusueh. They successfully reached Batavia and eventually Australia. The following day a further 59 nurses sailed on the Empire Star with more than 2,000 evacuees. It too reached Batavia but had been attacked en route with loss of life. Finally, on Thursday 12 February, the 65 remaining nurses had to go too.

Late in the afternoon, Pat and the other 2/10th AGH nurses rendezvoused at St. Andrew’s Cathedral in Singapore city with their peers from the 2/4th CCS and the 2/13th AGH. This latter unit had arrived in Malaya in September and set up at St. Patrick’s School on Singapore Island before relocating to Tampoi on the Malay Peninsula at the end of November. By the end of January, the unit had been forced to return to St. Patrick’s School.

Vyner Brooke

From the cathedral the nurses proceeded to Keppel Harbour. At the chaotic wharves they were taken out by tug to a small coastal steamer, the Vyner Brooke, and with as many as 150 others slipped away as evening fell.

That night the Vyner Brooke made little progress and spent much of Friday hiding among small islands. By the morning of Saturday 14 February, Captain Borton was approaching the entrance to Bangka Strait. At about 2.00 pm, six bombers were seen approaching. Borton began evasive manoeuvres, but these ultimately proved futile. The Vyner Brooke eventually sustained three direct hits, came to a standstill and began to list. It was 15 kilometres from Bangka Island.

The nurses hurried about the deck, helping women and children, the elderly, the wounded, and their own injured colleagues into the three viable lifeboats, which were then lowered into the sea. After a final search of the ship, it was the nurses’ turn to evacuate. They removed their shoes and their tin helmets and entered the water any way they could. Some jumped from the railing on the portside, others practically stepped into the water on the listing starboard side, others slid down ropes or climbed down ladders.

Pat found herself in the water. Around her, her colleagues and other passengers floated by on rafts or pieces of wreckage, in lifeboats, or simply bobbing in their lifebelts. The water was covered in oil from the ship’s engine, and here and there dead bodies floated motionless.

Bangka Island

Drifting on the current, Pat eventually reached the shore of Bangka Island, not far from the town of Muntok, and was picked up by Japanese troops and interned in the town cinema.

In the cinema were hundreds of survivors of dozens of ships sunk by Japanese forces over the past few days, including other surviving nurses. Two days later the internees were taken to workers’ barracks on the edge of town, and after a week or so, one more nurse arrived – Vivian Bullwinkel of the 2/13th AGH. She had miraculously survived a massacre that had claimed perhaps as many as 80 lives, including 21 of the nurses. Twelve others had been lost when the Vyner Brooke was sunk. Only 32 were still alive.

Pat and her comrades, together with many hundreds of women, children and men, spent the next three-and-a-half-years as prisoners of the Japanese. They were held in six camps on Bangka Island and in southern Sumatra. They were subjected to systematic abuse and random acts of violence. They were slapped, yelled at and made to stand in the sun. They were threatened with starvation and, by the end, nearly did starve. They suffered debilitating diseases, particularly in the final two camps, Muntok on Bangka Island and Belalau on Sumatra, and had life-saving medicines withheld. They were permitted to write home only once, a lettercard in March 1943, and received only two lots of mail from home. They were denied their rights under the Geneva Convention to be treated as prisoners of war. Worst of all, eight of their comrades died, all in 1945.

Rescue

On 16 September 1945 the surviving 24 nurses were plucked from the Sumatran jungle by an Australian Dakota aircraft and flown to Singapore. They were driven to St. Patrick’s School and taken into the care of the 2/14th AGH. Soon after they arrived, the nurses enjoyed the luxury of the first beds they had slept in for three and a half years.

The next day the nurses were interviewed by Australian journalists. Pat spoke to the newspaper correspondent A. E. Dunstan, whose copy was picked up by several newspapers in Australia. Dunstan noted Pat’s vitality and mental alertness despite her ordeal and “pathetic thinness,” and observed that she was able to discuss her experiences in a detached way without self-pity. She told him that

things were often hard, but probably in reality were not as bad as our friends might have imagined from reports of Hong Kong and Shanghai. One of our greatest anxieties was that we were unable to let our families know we were all right. The experience at Bangka Island was horrible, but once we were in prison camps the [Japanese] made no attempt to molest us, though they were fiendishly ingenious in discovering ways to humiliate us. I don’t think that they were able to get rid of their feeling of inferiority. We always felt that we were in a battle of wills. We were in the stronger position. Once when an officers’ club opened near the camp we were invited in. It was suggested that we should play cards and help the officers with their English. We refused to go and were told that we would be starved into agreeing, but the threat was never carried out and the matter dropped. Once the capitulation was announced the [Japanese] fairly grovelled. We had unlimited food – butter, eggs and chicken. Our cooking was done by friends from the male internee camp. Everything came right at once.

Pat spoke about the nurses’ obsession with recipes. They wrote them down in notebooks where they could, but when there was no light to write by, they contented themselves with simply talking recipes. “We really believed that talking about food did something to appease our terrible hunger,” she said. “Certainly it made our mouths water.”

Pat also told Dunstan that the nurses made playing cards for bridge from old albums and pieces of cardboard. “We also were allowed to hold concerts,” she said, “and in these our choir took part. The choir hummed melodies from music written out for us from memory by a missionary [Margaret Dryburgh].”

Return to Australia

On 5 October, after a period of recuperation, Pat and the others boarded the hospital ship Manunda in Keppel Harbour and sailed for home. Thousands of people turned out to see the arrival of the ship at Fremantle on 18 October. They cheered when the Manunda reached the wharf, flowers were showered on the nurses, and the 12-kilometre drive from the wharf to Hollywood Military Hospital was through crowded, cheering streets. Thousands of people wept openly.

After a night spent at the flower-decked hospital, the nurses continued their way east – all except Iole Harper and Ada ‘Mickey’ Syer. Late in the afternoon of 24 October the Manunda arrived in Melbourne. Pat and her comrades walked down the gangplank and through a guard of honour formed by between 40 and 50 members of the AANS. They were then greeted by the matron-in-chief of the AANS, Col. Annie Sage, who had been on the Dakota that had carried them to freedom from Sumatra. They boarded a bus and set out for Heidelberg Military Hospital, where they were given a welcome-home party. Pat and the other New South Wales and Queensland nurses spent the night in the hospital and the next day returned to the Manunda at Port Melbourne.

They sailed on to Sydney, their final stop. The ship arrived at Woolloomooloo on 27 October, and the nurses were taken to the 3rd Australian Women’s Hospital at Concord for observation and tests. Pat was home.

Life after captivity

Just over a month later, on 1 December, Pat married Lieut. Keith Menzies Dixon, 2nd AIF at the Shore College Chapel in North Sydney, to whom she had become engaged at the beginning of the war. They lived at 15 Glen Road, Roseville, just north of Chatswood.

After her marriage Pat got on with the rest of her life. She was discharged from the army in mid-1946, and eighteen months later, on 8 February 1948, her first child, a son, was born at Crown Street Women’s Hospital in Sydney. On 15 April 1950 another son was born.

For the rest of her life Pat remained in contact with the other surviving nurses. Theirs was a bond that no one who had not been through a similar experience would ever understand.

Pat’s father, George Blake, died on 29 June 1950. Seventeen years later Pat’s mother, Katie Florence Blake, died on 10 April 1967 at 12 Havilah Road, Lindfield, where she had been living since before 1932.

Keith passed away on 27 March 1997, when he and Pat were living in Toukley on the New South Wales Central Coast. Just over a year later, on 7 April 1998, Pat died at Lakeside Nursing Home in Toukley. She was 85 and had lived a long and extraordinary life. She was buried at Palmdale Lawn Cemetery & Memorial Park.

In memory of Pat.

Sources

- Ancestry.

- Goodman, R. (1985), Queensland Nurses: Boer War To Vietnam, Boolarong Press.

- Jeffrey, B. (1954), White Coolies, Angus & Robertson Publishers.

- National Archives of Australia.

- Shaw, I. W. (2010), On Radji Beach, Pan Macmillan Australia.

- Simons, J. E. (1956), While History Passed, William Heinemann Ltd.

Sources: Newspapers

- Australian Women’s Weekly (6 Oct 1945, p. 17), ‘Nurses’ terrible years in Sumatra prison camps.’

- The Daily Mirror (Sydney, 19 Oct 1945, p. 9), ‘How Nurses Died at Banka.’

- The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, 18 Sept 1945, p. 3), ‘Nurses “Like Skeletons”: Rage as A.I.F. See Survivors of Massacre.’

- The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, 2 Dec 1945, p. 38), ‘Women’s News.’

- Labor Daily (Sydney, 1 Aug 1932, p. 7), ‘Group Winners: Ladies’ Air Tourney Big Race, August 20.’

- Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (19 Sept 1945, p. 4), ‘Nurses Mentally Alert Although Painfully Thin.’

- News (Adelaide, 18 Sept 1945, p. 1), ‘Ingenious Efforts to Humiliate Nurses.’

- The Sun (Sydney, 19 Sept 1937, p. 10), ‘Tennis Tournament.’

- The Sun (Sydney, 2 Dec 1945, p. 12), ‘Gay Christmas parties this year for children.’

- The Sydney Morning Herald (23 Mar 1928, p. 4), ‘Family Notices.’

- The Sydney Morning Herald (22 May 1930, p. 4), ‘Abbotsleigh Old Girls’ Dance.’

- The Sydney Morning Herald (7 Jun 1932, p. 3), ‘Near and Far.’

- The Sydney Morning Herald (18 Dec 1936, p. 3), ‘General Branch.’