AANS │ Sister │ First World War │ Egypt │ No. 1 Australian General Hospital

Family Background

Norma Violet Mowbray was born on 20 October 1883 at St. George, Queensland. She was the daughter of Elizabeth Barclay Macalister (1850–1923) and Thomas Mowbray (1848–1914).

Elizabeth was born in Ipswich, Queensland and was the second daughter of the Hon. Arthur Macalister, MLA, a premier of Queensland. Thomas was born in Brisbane and was the son of the Rev. Thomas Mowbray.

Elizabeth and Thomas were married on 8 March 1873 in Townsville by the Rev. James Adams. At the time, Thomas was the manager of the Australian Joint Stock Bank, Charters Towers. Curiously, nine years earlier, Elizabeth’s elder sister had herself married a bank manager in a ceremony officiated by Thomas’s father.

After their wedding the couple lived in Charters Towers, and in January 1874 Elizabeth gave birth to their first child, Thomas Aubery Montaque. Later that year Thomas senior was appointed by the colonial government as the magistrate of Millchester, a town just south of Charters Towers. Then in October 1875 he was appointed police magistrate of St. George, a town 500 kilometres west of Brisbane. Tragically, soon after the Mowbrays’ arrival in early November, Thomas Aubery died, aged not yet two years.

The Mowbrays spent nine years at St. George, and during this time three children were born, Ida Tassie in 1879, Rupert Wallace in 1881, and Norma in 1883. In June 1884 Thomas was appointed police magistrate of Mackay, on the north Queensland coast. On 14 June, at a farewell held at the Australian Hotel in St. George, he was thanked for his service over such a long time and presented with a silver tea and coffee service.

During their stay in Mackay, three more children were born to the Mowbrays, Mabel Evelyn in 1885, Eileen Grahame in 1888 and finally Mina Elsie in 1890. Their family was complete. In November 1892, with Norma now nine years old, Thomas was transferred again, this time 700 kilometres south to Bundaberg, in the heart of Queensland’s sugarcane country. On 29 November he was very warmly feted by the officials of Mackay, and his health was drunk, together with that of Elizabeth and the children.

In Bundaberg Norma attended Mrs Boyle’s High School for Girls. In July 1899 she sat and passed the Junior Public Examination administered by Sydney University, gaining a second in English history and thirds in English, arithmetic and geology. In the same year Rupert Mowbray was attending Brisbane Boys’ Grammar School, presumably as a boarder.

With her schooling now completed, on 1 December 1903 Norma was the only candidate sitting an examination held at the Bundaberg Courthouse for admission to the State Civil Service. That same month, Thomas Mowbray was transferred once again, to Warwick, on the Darling Downs in southeastern Queensland. His police magistracy at Bundaberg had been his longest yet.

NURSING

We do not know how Norma fared in her State Civil Service examination, but regardless of the outcome, in 1905 she began to train as a nurse at Brisbane General Hospital. Among her cohort was a trainee by the name of Grace Wilson, who would in time become one of Australia’s best-known nurses. She served with distinction during the Great War and again during the Second World War.

While Norma was in Brisbane training to be a nurse, in December 1906 Thomas Mowbray was appointed police magistrate of Toowoomba, a large Darling Downs town. It would be his second-last transfer. In Toowoomba the Mowbrays lived at ‘Metoura’ on Clifford Street.

In November 1907 Norma passed her final nursing examination. That year she had finished first in medical nursing, fourth in surgical nursing, second in hygiene and diet, and scored well in her surgical instruments and practical examination. Only Grace Wilson achieved a higher average, and together they were the only two candidates to gain honours (for achieving an average of 90 per cent or more). Grace Wilson was awarded the hospital’s gold medal, and she and Norma were both warmly congratulated by Dr. McLean.

Having gained her certificate, Norma was appointed to the position of charge nurse at Warwick Hospital, around 80 kilometres from Toowoomba. She remained in the role for nearly two years before resigning towards the end of 1909 to take up an appointment as matron of Charleville Hospital, around 700 kilometres to the west of Brisbane.

Norma spent two years at Charleville. She resigned in 1912 and in mid-July that year departed for Melbourne to join the nursing staff of the Women’s Hospital. Meanwhile, at the beginning of July, Thomas Mowbray had commenced his duties as third police magistrate of Brisbane, having been transferred for the final time. The Mowbrays had moved into a house on Weinholt Street in Auchenflower, an inner suburb.

By May 1913 Norma had returned to Brisbane. She was living at her parents’ home in Auchenflower and had either begun to practise private nursing or was soon to begin. A year later, on 30 May 1914, Thomas Mowbray died suddenly at home. He had had a long-standing heart condition.

ENLISTMENT

In August 1914 Australia went to war. Norma’s brother, Rupert, almost immediately joined the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force and served in the southwest Pacific.

Norma also wanted to serve her country and applied to join the Australian Army Nursing Service. In October she was among a contingent of Queensland AANS nurses appointed to No. 1 Australian General Hospital (AGH) of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF). Their names were released on 28 October 1914 by the acting principal medical officer, Major David Gifford Croll (the husband of Sister Winifred Croll, one of the appointees) and supplied to the press by the chief matron of the 1st Military District (Queensland) – none other than Grace Wilson.

Norma had been assigned the rank of sister, and as such she would receive a salary of £100 4s per annum plus 3s 6d per diem field allowance. Staff nurses, on the other hand, would be paid £60 per annum, with a per diem field allowance of 2s 6d.

On 11 November Norma and other Queensland No. 1 AGH appointees enlisted in Brisbane. Over the next ten days they received their uniforms, attended parades and lectures, had a group photo taken, received their kit allowance, and packed. On 20 November they were ordered to be on board HMAT Kyarra at 3.00 pm the following day. They were bound for Egypt.

THE VOYAGE OF THE KYARRA

On 21 November, having boarded by the appointed hour, around 193 staff of No. 1 AGH – 23 AANS nurses and 170 officers, NCOs and other ranks – departed Brisbane on HMAT Kyarra. They were given a memorable send off by the people of Brisbane. Before departure, each nurse had been presented to Helen Munro Ferguson, founder of the Australian Branch of the British Red Cross Society (and wife of Sir Ronald Munro Ferguson, Governor-General of Australia).

Late on 23 November the Kyarra arrived at Sydney Harbour and berthed at the Orient Wharf, Circular Quay. Most of the nurses disembarked to sleep onshore, with only seven remaining on board. By the time the Kyarra departed again at around 4.00 pm on 25 November, the staff of No. 2 AGH, also bound for Egypt, had joined their No. 1 AGH peers on board. Among them were 42 sisters and staff nurses.

On 28 November the Kyarra arrived in Melbourne, and here Norma and the others spent a week. When the ship departed again on 5 December the Queensland nurses of No. 1 AGH had been joined by 43 Victorian nurses, among them Principal Matron Jane Bell. Forty nurses of No. 2 AGH boarded as well, as did staff of No. 1 Australian Stationary Hospital and No. 1 Australian Clearing Hospital (later known as No. 1 Casualty Clearing Station). Neither unit had AANS nurses on staff.

The Kyarra’s next port of call was Fremantle. The ship arrived on 11 December and, after embarking No. 2 Australian Stationary Hospital, departed at around 6.00 pm on 14 December.

On Christmas Eve the Kyarra crossed the Equator, with the usual mock humiliations, and then Christmas Day arrived. Church services were held, and No. 1 AGH nurses enjoyed Christmas dinner. The nurses were shouted champagne by Captain Alcorn and they drank the King’s health. Another dinner was held at 8.00 pm and lasted nearly two hours.

The Kyarra arrived at Colombo on Boxing Day and the nurses went ashore the following morning. For the next two days they saw many of the sights of the colourful colonial town. They took carriages to Victoria Park (now called Viharamahadevi Park), located in the area known as Cinnamon Gardens. They visited local neighbourhoods, saw a Buddhist temple, and had lunch at the Grand Oriental Hotel. They visited shops, took rickshaws, and had afternoon tea at the Galle Face Hotel. They witnessed a funeral procession and passed through the Hindu quarter, noting temples with numerous tiny lights. They visited the Gordon Gardens, near the Fort, with its Portuguese-inscribed rock.

At around 8.00 pm on 29 December the Kyarra sailed again. New Year’s Eve arrived, and the nurses attended a fancy-dress masque ball followed by supper at 11.30 pm provided by the officers. They welcomed in 1915 with singing and cheering and once again toasted the King’s health.

Norma and her colleagues were now only two weeks from their destination. On 4 January the Kyarra passed Socotra at the entrance to the Gulf of Aden and two days later arrived at Aden. The nurses were not permitted to go ashore but locals in small boats came out to the Kyarra selling such things as ostrich-feather fans.

On the morning of 7 January the Kyarra passed through the Bab al-Mandab and entered the Red Sea. By 11 January it had reached the Gulf of Suez, with Mt. Sinai on the right, and at around 8.00 pm that night had arrived at Suez. After an overnight stop, the Kyarra raised anchor in the early afternoon of 12 January and entered the Suez Canal. Port Said was reached on 13 January and the nurses went ashore. They had morning tea at the Eastern Exchange Hotel and lunch at the Casino Palace Hotel and then went for a gharry ride. The Kyarra departed at around 6.00 pm and the next day, 14 January, Norma arrived in Alexandria, Egypt’s Mediterranean metropolis.

HELIOPOLIS, EGYPT

The nurses of both units remained on board the Kyarra while awaiting disembarkation orders. However, as they were freely given shore leave, the time was spent pleasantly enough coming and going between the ship and Alexandria. Parties of nurses even day tripped to Cairo.

Finally movement orders came for the staff of No. 2 AGH. On 20 January they left the Kyarra and entrained for Cairo, then proceeded to Mena House, a luxury hotel and former royal hunting lodge located close to the Pyramids of Giza. Here the No. 2 AGH nurses joined their compatriots Matron Nellie Gould, Matron Julia Johnston, Sister Adelaide Kellett and others, who had arrived in Egypt on 3 December 1914 with 20,000 men of the First Expeditionary Force and had taken over a British hospital at Mena House.

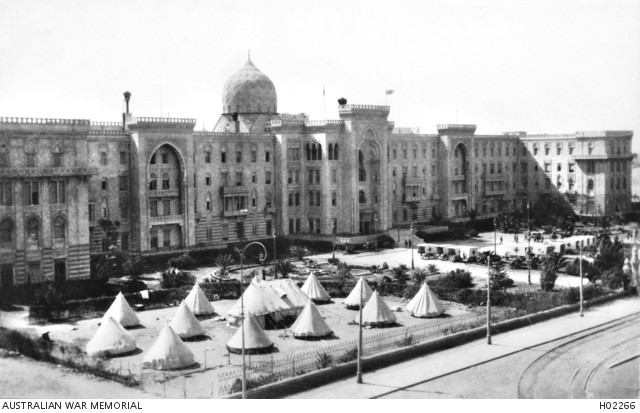

Soon it was the turn of Norma and the other staff of No. 1 AGH to move. At around 9.00 am on 24 January they entrained for Cairo and made their way to the Heliopolis Palace Hotel, located in Heliopolis, a new suburb lying 10 kilometres northeast of central Cairo and named after an ancient Egyptian city. When they arrived at around 1.00 pm nothing was ready and there were of course no patients. Now, in the words of Norma’s No. 1 AGH colleague Sister Emma Cuthbert, “the pioneering work was to commence.” The following day the hospital’s equipment began to turn up and the orderlies soon got busy opening packing cases.

To begin with, there were relatively few patients for No. 1 AGH to treat. The majority of the troops of the First Expeditionary Force were camped close to Mena House, and so it was there that they were treated. However, with the arrival of troops of the 2nd Division in early February, the number of patients, mainly medical cases, treated at the Heliopolis Palace Hotel increased steadily, especially as Mena House was soon filled. By 15 February there were a good many patients, many with pneumonia and empyema. In response, the unit began to rationalise the spaces within the hotel. Valuable furniture, carpets and curtains were stored away in various rooms, and the only hotel furniture used from then on was beds and bedding for the officers and nurses.

Meanwhile, on 7 February No. 1 AGH had been directed to staff and equip a tented venereal diseases hospital at the Australian camp at Heliopolis Aerodrome, quickly followed by a tented infectious diseases hospital alongside. Soon a small, tented camp for infectious diseases was set up in the grounds of the Heliopolis Palace Hotel itself, which was staffed by one of the nurses, and to which all serious cases were sent.

The first hot winds of spring in March, however, warned everyone concerned that patients could not be treated satisfactorily in tents in midsummer. Therefore, two rooms in one wing of the hotel were given over to bad infectious cases, and the camp in the grounds was abolished. The arrangement proved unsatisfactory, and finally a portion of the Abbassia Military Barracks, located around four kilometres closer to central Cairo, was obtained, and converted into a venereal diseases hospital to which the venereal cases were then transferred.

THE GALLIPOLI CAMPAIGN

In early April the Australian troops moved out of their camps at Mena, Heliopolis and elsewhere and proceeded to Alexandria, from where they sailed to the Greek island of Lemnos. Lemnos lay around 100 kilometres to the west of the Gallipoli Peninsula and it was here, in Mudros Harbour, that the Allied forces based themselves prior to the Gallipoli landings.

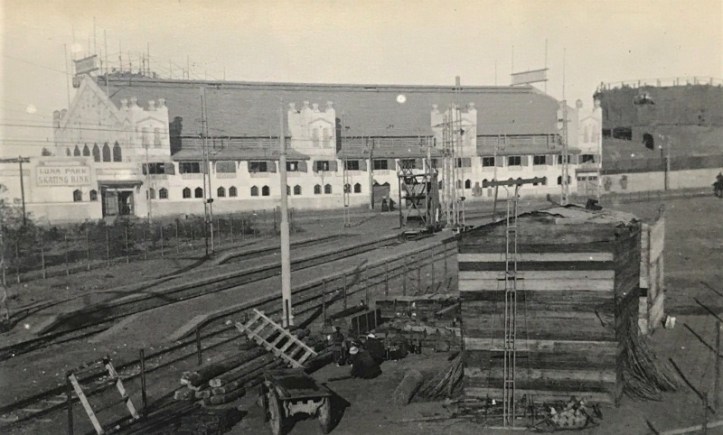

With the Gallipoli campaign imminent, No. 1 AGH began to prepare for the reception of casualties, and nearby buildings were progressively taken over. The wooden skating-rink of a pleasure resort, Luna Park, was obtained, and the infectious cases from the tented camp at the hotel were transferred across to it. Once a camp kitchen was built, it made a fine open-air infectious diseases hospital accommodating around 750 patients. However, it became clear that the skating rink might better serve as an overflow hospital should mass casualties ensue from the Gallipoli campaign, and accordingly efforts were made to obtain another infectious diseases hospital in the vicinity. A building known as the Racecourse Casino, a few hundred metres from the Heliopolis Palace Hotel, was obtained and converted into an infectious diseases hospital providing for the accommodation of about 200 patients. The patients were transferred to here from the skating rink, which now was empty and ready for the reception of overflow cases from the hotel.

On 25 April, 16,000 Australian and New Zealand troops set out from Mudros Harbour on Lemnos bound for Ari Burnu on the Gallipoli Peninsula. Ari Burnu would very soon be known as Anzac Cove. By 7.00 am the landings were well underway. Just after 9.00 am the first casualties were brought to the waiting hospital ship Gascon, anchored at some distance from the coast so as to avoid Turkish artillery. The wounded men were ferried from the beaches of Gallipoli on transports, lighters, launches and torpedo boats.

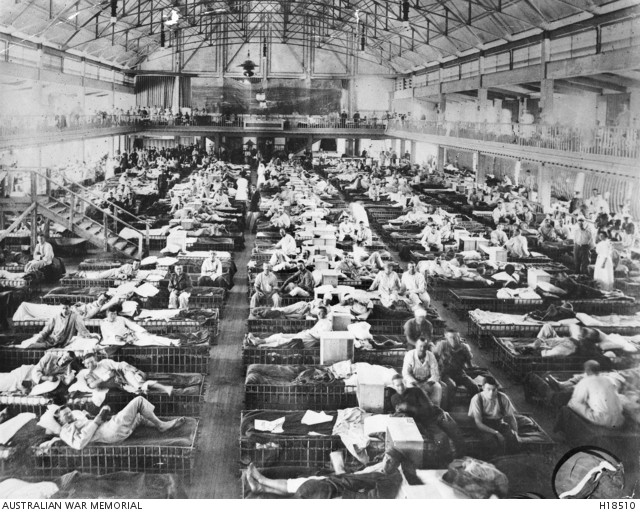

By the evening of 25 April, with no more room available, the Gascon left for Mudros Harbour with around 550 casualties – almost half of the approximately 1,300 Anzac soldiers wounded on that first day. The ship was left waiting in the harbour until the evening of 26 April, and then ordered to sail to Alexandria, arriving there in the small hours of 29 April. Fourteen of the wounded had died during the voyage. Throughout the day, 535 wounded were unloaded and put on trains bound for Cairo, from where many were then transferred to No. 1 AGH.

In the nick of time, it had been found possible to run trains on the tramlines that ran between central Cairo and the Heliopolis Palace Hotel. A trial run was made late on 27 April, and the following evening the first train arrived from Cairo carrying around 150 sick patients from Lemnos. The next night, Thursday 29 April, battle casualties from the beaches of Gallipoli began to pour into Heliopolis. In a letter home dated 7 May, Norma’s No. 1 AGH colleague and fellow Queenslander Sister Constance Keys described their arrival:

The hospital train came right behind the Palace, nine long white carriages with the Egyptian star and crescent on the side. Then the unloading commenced. Those who could walk were shown the way in & those on stretchers were carried over in the motor ambulances. I’ll never forget the sight of those hundreds of men walking & being carried in, one after the other in endless procession. There wasn’t a sound except footfalls then the wards commenced to fill up. The work of getting those weary men washed, wounds dressed & fed was a big undertaking, but it was done.

Another fellow Queenslander, Senior Sister Agnes Isambert, recorded in her diary that around 500 casualties arrived that night. The following night, Friday 30 April, was worse:

Tram loads of wounded arrived again today, some very bad indeed & lots transferred to our overflow hospital Luna Park & others to Mena hospital. Infectious diseases measles all moved from Luna Park to Racecourse [Casino] a little further on.

Two train loads of wounded came in on Saturday, noted Agnes Isambert. While the first load was not too badly injured,

a tram load arrived at 12 midnight about 140 very badly wounded, a great lot of whom are going to die. Oh the horror of this war, the boys are so proud of themselves. Are so good about their wounds & dressings – so many are going to be cripples & loose [sic] their limbs. Doctors operating all night – not going to bed until 5 am. Theatre nurses also & most of the day staff staying up until midnight.

Sunday was even worse. Four different operating tables were going all day until midnight. The numbers eased off marginally the next day, 3 May. Most of the wounded were transferred to Luna Park, with only the very serious cases staying at the Heliopolis Palace Hotel.

Norma and the other nurses had never before been exposed to such a stream of horrific injuries. Emma Cuthbert wrote that “the whole situation was so new to us, that many a sister when the badly wounded first arrived, had to at times suddenly disappear into the pantry to control her feelings for these poor suffering boys.” However, through sheer necessity they soon learned to steel themselves against emotional responses and got on with the dispassionate business of dealing with awful, shocking wounds.

THE EXPANSION OF No. 1 AGH

During the first ten days of the campaign approximately 16,000 wounded men entered Egypt, of whom the greater number was sent to Cairo – and of these, most went to No. 1 AGH. Fortunately, Australian Army Medical Corps (AAMC) personnel had been proactive and the supply of beds was just managing to keep up with demand. As soon as the nature of the engagement at Gallipoli became known, No. 1 AGH was ordered to take over and equip the upper pavilion section of Luna Park. It was made ready for the reception of the wounded within a few hours, and within a few days Luna Park as a whole could accommodate 1,650 patients. Meanwhile, the Heliopolis Palace Hotel continued to rationalise its space. All of the furniture was now moved into corridors of the building and subsequently removed altogether and stored elsewhere.

As the campaign continued, many more buildings were acquired and converted into general hospitals, infectious and venereal diseases hospitals, and convalescent hospitals. To the credit of the AAMC and of the staff of No. 1 AGH, this dramatic expansion was achieved by the end of July, and the 520-bed hospital which had landed in Egypt on 25 January had expanded into a 10,000-bed, multicampus hospital.

THE AUGUST OFFENSIVE

In August a new offensive was opened by the Allies that was aimed at capturing the heights of Sari Bair above Anzac Cove. As part of the offensive, between 6 and 10 August Australian troops fought the diversionary Battle of Lone Pine. They captured the position but at the cost of some 2,277 casualties with no strategic gain. On 7 August, in another feint, Australian troops fought the Battle of the Nek, suffering 372 casualties for no gain whatsoever.

The first battle casualties from the renewed fighting reached Heliopolis soon after the offensive began, and by the middle of the month many men were arriving with terrible wounds. “The wounds are just as awful now as when we had the bad cases before,” Agnes Isambert wrote in her diary entry of 18 August, “so awfully smelly, some nearly make you sick doing their dressings but a good many seem to be getting on alight, some have had to have their arms amputated.” Many medical cases were arriving as well, due to conditions in the trenches.

By 26 August it had become apparent to the nurses, based on what their patients were telling them, that the August offensive had failed. It was incomprehensible that so many lives had been expended for nothing. Among those killed was Norma’s brother-in-law, Captain John Fitzmaurice Guy Luther – Ida Mowbray’s husband – who died on 25 August. Guy, as he was known, had enlisted on 6 October 1914 and had landed at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915 as a medical officer attached to the 15th Battalion, 3rd Infantry Brigade. Norma was extremely upset at the news and volunteered with others for duty on a ship transporting wounded and ill patients to Australia.

RETURN TO AUSTRALIA

On 9.30 am on 3 September, Norma and her colleagues Staff Nurses Florence Graham, Bertha McKinnell, Elizabeth Palmer and Mary Weston departed Heliopolis for Suez, and on 4 September they departed for Australia on HMAT Ulysses. Among the other AANS nurses assigned to the ship were Staff Nurses Amy Walker McNulty and Ruby Nicholls of No. 2 AGH.

The Ulysses arrived in Sydney on 2 October. Two days later Norma and Ruby Nicholls, who was from Toowoomba, entrained for Brisbane accompanying wounded and invalided soldiers on their return home. After visiting her mother in Brisbane, Norma spent some weeks with her bereaved sister at Southport. She was able to convey to Ida some details of Guy’s death.

Before Norma returned to Egypt in mid-November, she penned a letter to a certain Miss Thorburn (possibly Nessie Thorburn, president of the Girls’ Patriotic Committee in Bundaberg), part of which was reprinted in the Bundaberg Mail and Burnett Advertiser on 20 November 1915.

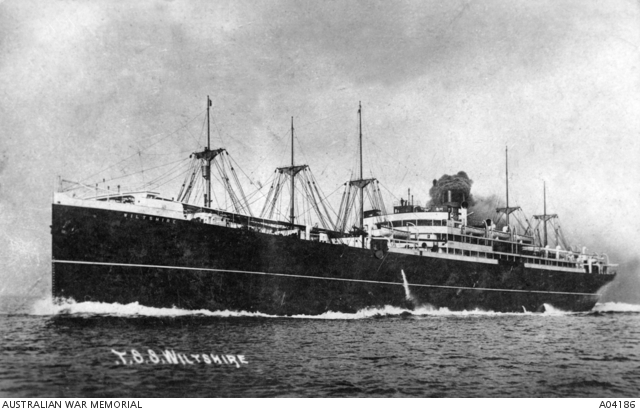

If eggs will carry well over to Egypt they would be most acceptable, for we use any amount of them in the hospitals. In one place alone they use hundreds a day. As for the sandbags, I know that in Gallipoli they want all they can get, so your small boys will be doing a great deal if they go on making sandbags. We are staying in Melbourne until Thursday [18 November], and then going by the Wiltshire. We are taking mostly artillery men with us in our boat.

RETURN TO EGYPT

On 13 November Norma left Brisbane for Sydney en route for Egypt once again. The previous day she had attended a presentation of band instruments and afternoon tea organised for the officers of the 15th Battalion. From Sydney Norma entrained for Melbourne and on 18 November duly departed on HMAT Wiltshire. The Wiltshire was carrying around 1,000 AIF personnel and 200 horses to Egypt.

On 15 December the Wiltshire arrived at Suez. Norma disembarked, entrained for Cairo, and arrived at the Heliopolis Palace Hotel on the same day. She had only been back for a few weeks when she contracted bronchitis.

ILLNESS

Norma was admitted to No. 1 AGH as a patient on 10 January 1916. In her diary entry of that day, Agnes Isambert noted that “Mowbray was warded today with a very bad cold & some temperature.” Norma was diagnosed with mild bronchitis and was discharged to duty on 14 January.

On 16 January Agnes Isambert found that Norma was “very ill running a temperature of 104 degrees & [looking] very ill.” For some reason, however, Elizabeth Mowbray was sent an official cable stating that her daughter was suffering from an attack of mild bronchitis. By the tone of the cable she would not have been particularly alarmed.

Norma was diagnosed with pneumonia on 17 January and continued to deteriorate. “We are all very anxious about Mowbray, who has been moved into a room to herself & has Special Nurses,” Agnes Isambert wrote on 18 January.

She looks as if she is not going to get better – she has been put on the dangerously ill list & her great pal Sister Baker is doing day special. Major Summers did not put her on D. I. list until after I had seen Major McLean who spoke to the O.C. He had a radiator put in her room & a mat on the corridor & in front of her room. It has made everyone feel terribly gloomy.

On 20 January Agnes wrote the following:

Poor Mowbray very ill almost unmanageable at times. Baker came to see me to see if I could do anything with her – I calmed her down & she allowed me to give her the hypodermic injection. She asked me to stay with her for a while which I did, she then told me she was going to die & that I thought so too & so did Colonel McLean.

Norma died at 10.40 am on 21 January 1916.

FUNERAL

Norma was buried the day after her death at the English Cemetery (also known as the Cairo War Cemetery and today as the Cairo War Memorial Cemetery). A poignant account of her funeral comes from Lance Corporal H. A. Larsen, who referred to it in a letter to his mother in Fairymead, Bundaberg. The account was printed in the Bundaberg Mail and Burnett Advertiser on 13 March 1916:

You will be sorry to hear that Nurse Mowbray, sister of Mrs. Dr. Luther, has died from pneumonia. She was buried with full military honors. It was a sad sight; accompanied by the Matron of the hospital and a mate I attended the funeral. The coffin was conveyed to the cemetery gates in an ambulance motor car; six nurses acted as pall-bearers; being unable to carry the coffin, six A.M.C. sergeants fulfilled that duty; then followed two chaplains, about a dozen officers, 40 nurses, 40 A.M.C. men, and a firing party of 32, in the order given. A band followed in the rear of the firing party, and played the ‘Dead March in Saul.’ After the burial service had been conducted at the graveside, the firing party fired three volleys and a bugler blew the ‘Last Post.’

Remembrance

Norma’s sacrifice was immediately recognised and continues to be acknowledged throughout Australia, in England, and in Egypt, where her grave at the Cairo War Memorial Cemetery can easily be visited.

We will not forget her.

SOURCEs

- Ancestry.

- Australian War Memorial, ‘Captain John Fitzmaurice Guy Luther, Medical Officer to the 15th Battalion, AIF.’

- Australian War Memorial, Unit Embarkation Nominal Rolls, 1914–18 War, ‘AWM8 26/65/1 – 1 Australian General Hospital (November 1914).’

- Australian War Memorial, Unit Embarkation Nominal Rolls, 1914–18 War, ‘AWM8 26/65/3 – 1 Australian General Hospital – 1 to 6 and Special Reinforcements (February 1915 – April 1916).’

- Australian War Memorial, Unit embarkation nominal rolls, 1914–18 War, ‘AWM8 26/66/1 – 2 Australian General Hospital (November 1914).’

- Australian War Memorial, Nurses’ Narratives, AWM41 958 – Sister E. H. [sic] Cuthbert.

- Barrett, J. W. and Percival E. Deane, P. E. (1918), The Australian Army Medical Corps In Egypt, Project Gutenberg.

- National Archives of Australia.

- State Library of Queensland, ‘Agnes Katharine Isambert Diary (item no. 30894/1).’

- State Library of Queensland, Constance Mabel Keys collection, Series 5: Correspondence (1914–1961), ‘Letterbook (24 September 1914–22 June 1916) (item no. 30674/36).’

- Through These Lines (website), ‘No. 1 Australian General Hospital.’

- Tregarthen, G., Sea Transport of the A.I.F., Naval Transport Board (available through Australian National Maritime Museum website).

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS

- The Argus (Melbourne, 19 Jul 1915, p. 8), ‘Back from the War.’

- The Brisbane Courier (11 Jul 1864, p. 2), ‘Family Notices.’

- The Brisbane Courier (15 Mar 1873, p. 4), ‘Family Notices.’

- The Brisbane Courier (17 Jun 1884, p. 5), ‘Queensland News.’

- The Brisbane Courier (19 Jun 1884, p. 5), ‘No title.’

- The Brisbane Courier (14 Jun 1907, p. 4), ‘Invalid Cookery Examination.’

- The Brisbane Courier (3 Feb 1916, p. 9), ‘Death of Miss Norma Mowbray.’

- The Bundaberg Mail and Burnett Advertiser (Qld., 2 Dec 1903, p. 3), ‘Local and General News.’

- The Bundaberg Mail and Burnett Advertiser (Qld., 12 Nov 1907, p. 3), ‘Personal.’

- The Bundaberg Mail and Burnett Advertiser (Qld., 11 Oct 1909, p. 2), ‘Mainly about People.’

- The Bundaberg Mail and Burnett Advertiser (Qld., 20 Nov 1915, p. 2), ‘Eggs and Sandbags.’

- The Bundaberg Mail and Burnett Advertiser (Qld., 13 Mar 1916, p. 3), ‘Death of Sister Mowbray.’

- Dalby Herald and Western Queensland Advertiser (Qld., 30 Oct 1875, p. 2), ‘Notes and News.’

- Darling Downs Gazette (Toowoomba, Qld., 5 Jan 1907, p. 4), ‘Personal.’

- Darling Downs Gazette (Toowoomba, Qld., 5 Oct 1910, p. 5), ‘Wedding.’

- Darling Downs Gazette (Toowoomba, Qld., 1 Nov 1910, p. 8), ‘Le Beau Monde.’

- Darling Downs Gazette (Toowoomba, Qld., 22 Jul 1912, p. 5), ‘Le Beau Monde.’

- Mackay Mercury (Qld., 27 Oct 1892, p. 2), ‘No title.’

- Mackay Mercury (Qld., 1 Dec 1892, p. 2), ‘Presentation to T. Mowbray, Esq.’

- Mackay Mercury (Qld., 3 Dec 1903, p. 2), ‘Telegrams.’

- The Northern Miner (Charters Towers, Qld., 18 Aug 1875, p. 2), ‘Notes and Events.’

- The Queenslander (Brisbane, 29 Jul 1899, p. 228), ‘Educational.’

- Queensland Figaro (Brisbane, 29 May 1913, p. 9), ‘Gossip from Women’s Clubland.’

- Queensland Times (Ipswich, Qld., 29 Oct 1914, p. 2), ‘Nurses for the War.’

- Rockhampton Bulletin (Qld., 9 Jan 1875, p. 3), ‘List of Magistrates.’

- The Telegraph (Brisbane, 30 Oct 1875, p. 2), ‘Official Notifications.’

- The Telegraph (Brisbane, 14 Jun 1907, p. 3), ‘Advertising.’

- The Telegraph (Brisbane, 21 Nov 1907, p. 3), ‘Brisbane Hospital.’

- The Telegraph (Brisbane, 23 Sept 1909, p. 2), ‘Wedding.’

- The Telegraph (Brisbane, 13 Nov 1914, p. 5), ‘Social and Personal.’

- The Telegraph (Brisbane, 24 Nov 1923, p. 12), ‘Death of Mrs. Mowbray.’

- The Telegraph (Brisbane, 5 Oct 1915, p. 2), ‘Military Nurse.’

- The Telegraph (Brisbane, 12 Nov 1915, p. eight), ‘Social and Personal.’

- The Telegraph (Brisbane, 19 Apr 1916, p. 2), ‘Brisbane Hospital.’

- Warwick Examiner and Times (Qld., 30 Dec 1903, p. 3), ‘Local Items.’

- Warwick Examiner and Times (Qld., 1 Dec 1906, p. 8), ‘Transfers and Promotions.’

- Warwick Examiner and Times (Qld., 30 Sept 1908, p. 5), ‘Warwick Hospital.’

- Warwick Examiner and Times (Qld., 30 Sept 1908, p. 8), ‘Personal.’

- Warwick Examiner and Times (Qld., 1 Jun 1914, p. 4), ‘Obituary.’

- Warwick Examiner and Times (Qld., 6 Oct 1915, p. 1), ‘Social Gossip.’