QAIMNSR │ Staff Nurse │ First World War │ France & England

FAMILY BACKGROUND

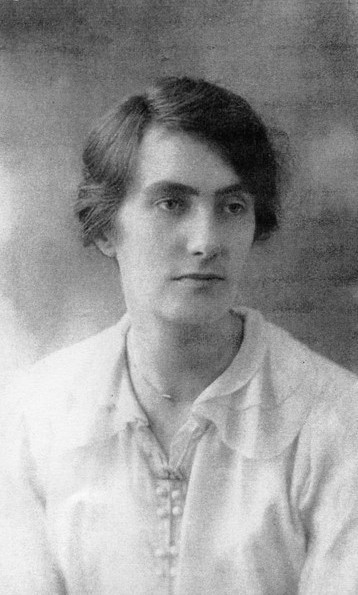

Nellie Mabel Saw was born on 4 March 1890 in Albany, Western Australia. She was the fourth of six children born to Eliza Cooper (1858–1945) and Thomas Henry Saw (1853–1945).

Eliza was the daughter of James Cooper of Leicestershire and Sarah Ann Waters of Norfolk and was born in Fremantle. Thomas was born in Perth and was the son of Thomas Henry Ebenezer Saw of Oxfordshire and Harriett Gibbs of London.

Eliza and Thomas were married on 17 January 1884 at St. John’s Church in Albany. Thomas’s first marriage, to Fanny Jane Snook, had ended with Fanny’s death on 22 April 1882, the day after the birth of their daughter, Fanny Helen (1882–1967). A child born in 1880, Thomas Henry William, had died in infancy.

After their marriage Eliza and Thomas lived in Albany with little Fanny Helen. They added to their family with the birth of Lily Hilda in 1884, followed by Herbert Thomas (known as Bert) in 1886, Cecil George in 1888, Nellie in 1890, Violet Ethelwynne (known as Ethelwynne) in 1892 and Clarence Henry in 1895.

As early as 1887 Thomas was a seller of seeds – vegetables, grasses, trees etc – as his uncle Ebenezer Saw had been. By 1900 Thomas was selling plants and fresh-cut flowers as well as seeds from premises on York Street in Albany.

CHILDHOOD

As a child Nellie went to Albany Grammar School. She also attended the Sunday School held at the Wesley Church on Duke Street in Albany.

Nellie was a talented painter. At the 1905 Albany Show, held in December, both of her entries in the under 16 oil painting competition, one a stag and the other a piece of fruit, were disqualified by the judge, who thought they were so good that they could not possibly have been executed by a child under 16. In protest, Nellie’s art teacher, Elsie James, wrote to the Albany Advertiser stating in unequivocal terms that the paintings were indeed Nellie’s own, unaided work and that she was entitled to first prize. Earlier that year Nellie had arrived at the Children’s Ball, an integral part of Albany Week, dressed as a ‘Painting.’ Nellie’s sister Ethelwynne was ‘Early Victoria’ while her brother Clarence was ‘British tar.’

Unsurprisingly, Nellie was also good at drawing. For two years running she was awarded the Class VI prize for drawing at Albany Grammar School.

NURSING, ENLISTMENT AND EMBARKATION

When Nellie grew up she decided to follow her elder sister Lily into nursing and commenced as a probationer at the Perth Public Hospital, where Lily had trained. After gaining her certificate she spent some time at the Victoria Hospital for Infectious Diseases in West Subiaco before returning to Perth Public Hospital.

She was working at Perth Public Hospital when the Great War erupted in Europe in August 1914. Its ripples were immediately felt in Australia. Thousands of Australian men applied to join the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) and hundreds of Australian women applied to join the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS).

By the end of 1915 Nellie was ready to play her part. On 13 December she applied in Perth for enlistment in the AIF, intending to join the AANS. However, a few days later Matron offered her a vacancy with the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC), the British equivalent of the Australian Army Medical Corps (AAMC). Happy at the prospect of following her sister Lily overseas, Nellie accepted, and on 17 December signed a contract with the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service Reserve (QAIMNSR), the British equivalent of the AANS.

Nellie embarked from Fremantle on 24 December 1915 and after several transhipments reached London on 10 February 1916. On the same day she was officially appointed to the QAIMNSR. She was subsequently posted to the Wharncliffe War Hospital in Sheffield.

FRANCE

On Sunday 2 April 1916 Nellie embarked for France with elements of the British Expeditionary Force. She was being posted to No. 26 General Hospital (GH) in Étaples, an old fishing town and port in the Pas de Calais and a hub for Allied military hospitals. No. 26 GH had arrived in Étaples in June 1915 and had a capacity of 1,040 beds spread across 35 wooden huts and a galvanised iron block of four wards.

In April Nellie wrote a letter to her family in which she describes her arrival in France and her subsequent experiences. It was partly printed in the Albany Advertiser on 15 July. She began her letter on 12 April.

No. 26 General Hospital, B.E.F. France, April 12, 1916. – We crossed on Sunday. It was a perfect day and the two hours we spent on the water were glorious. We were met and taken to the Hotel Louvre, where we were interviewed by the matron-in-chief for France [Maud McCarthy]. Next day we left Boulogne for our present abode [No. 26 GH] which is about 26 miles away. This hospital is going to take only our boys in from now on, so we will feel quite at home later on. I have only one Australian boy in my ward. One just gets to know their patients here, when they are passed on to various hospitals in England. My ward is very nice, zinc buildings and asbestos lined. I had expected tents, so was pleasantly surprised. The Canadian hospital next ours [No. 1 Canadian GH], consists of tents. My ward has 25 beds, not all full at present. A few days ago they were, as it was my turn to receive a convoy, but some have now gone on to ‘Blighty.’ We are quite close to a tidal river [Canche], just about three minutes walk from here. I have been for several tramps along the shore for miles. It is so fascinating. Of a morning, when the tide comes in, I can see from my windows the fishing boats sailing up the river. They look so pretty when the sun is shining. Up until the last few days we have had lovely weather, but it is so bleak and cold at present. I have walked miles every day, either along the road into the forests or on the river shore. I had a half-day off Monday and went with another nurse to Paris Plage. It is such a charming little seaport, with a lovely esplanade. In peace-time it was a great seaside resort. Now, most of the big hotels are either closed or turned into military hospitals. We are very comfortable here, two in a room, and we furnish it with our own camp kit and anything else we may like at our own expense. My pal and I are beginning to get ours quite snug.

Nellie continued her letter on 24 April, Easter Sunday.

Some of the girls got up at 4.30 a.m. to put flowers on all the soldiers’ graves up at the little cemetery. We had all contributed towards them. I went up in the afternoon. It looked very pathetic. Every grave was strewn with flowers over the mounds with their little wooden crosses at the heads. It’s only a small place, out among the sand dunes between the road and the river. There were lots of khaki-clad visitors and sisters. The scene made me feel rather morbid for a time, so I went for a long walk over the sand dunes, up a pretty little brook, through the woods, and along the beach to our quarters, and arrived back feeling quite fresh for the blow.

The concluding passage was written on 26 April.

Yesterday was Anzac Day. They had great celebrations here. I went to the open-air memorial service in the morning. All the Australian sisters had been particularly invited. The crowd looked very impressive; upwards of 5,000 were present. It was held in a large green sloping field, which is surrounded by fur covered hillocks, which were dotted with hundreds of blue-coated patients from the hospitals, khaki-clad and grey and red sisters. It looked grand in the bright sunlight. They have very nice Y.M.C.A. concert-halls about here. Each company generally gives two performances, one for the patients and one for sisters and officers. There is lots of news I would like to tell you, but we are not allowed. We have a very nice club for sisters close by – a very comfortable reading-room, small library attached and a tea-room. So think I will squander a few centimes this afternoon on something dainty, instead of partaking of our homely bread and jam. I had a very nice outing yesterday. We went by motor ambulances to ‘Villa Tino’ – a home for sick sisters – and saw some Australian friends there. It is a beautiful home, belonging to a Count, and they have every luxury. The woods surrounding are just perfect. We afterwards walked through them to Paris Plage. I never regret one moment for having come away. Life here is a throbbing vital thing to me, although some or most of the people around here get ‘fed up,’ as they term it. I have not reached that stage yet and hope I never shall, although the sadness of the whole business would threaten to get one down at times, if you stopped to think, which is a fatal error. All one has to do is to work hard and play hard off duty. It is the only way to keep fit.

Not long after this, Nellie became unwell. From 14 to 20 June she was admitted to hospital at Le Touquet – perhaps No. 1 British Red Cross Hospital. She was suffering from pleurisy, a condition of the chest that is sometimes suggestive of the presence of tuberculosis.

THE SOMME OFFENSIVE

When Nellie returned to No. 26 GH, the hospital was preparing for the Somme offensive. The hospital had been instructed to expand by 25 per cent, and in response large marquee tents were pitched. It was asked to expand further, and beds were added to the permanent wards. Finally it expanded a third time, to a total of 2,010 beds, and more tents were pitched.

The Battle of the Somme began on 1 July 1916. The human cost was staggering. The first day resulted in some 57,000 British casualties, of whom 20,000 were killed. During the first four days, ambulance trains carried more than 33,000 casualties from clearing stations to general hospitals.

Casualties began to arrive at No. 26 GH on 2 July. The greater proportion of these first arrivals were very slight cases, but for the next three days, 3–5 July, very seriously wounded men were brought in. From 2–5 July, a total of 940 battle casualties were brought in, 495 of whom arrived on 3 July alone. That same day 79 non-battle casualties were also received from the front, together with 21 local cases, bringing the total number of admissions on 3 July to 595.

During these first few days of the offensive, Nellie and the other nurses, together with the surgeons, the orderlies, the ambulance drivers – everyone – worked for hours and hours non-stop each day, doing all they could to keep their patients stable and comfortable.

As time passed, Nellie’s health deteriorated, and on 1 September she was admitted to hospital – whether at No. 26 GH or elsewhere is unknown – with broncho-pneumonia. Her condition became sufficiently serious to warrant her return to England.

ENGLAND

On 4 October 1916 Nellie was invalided to England, possibly to the Queen Alexandra Military Hospital at Vincent Square in London. At a meeting of a medical board at the hospital on 24 October she was granted sick leave to 23 November.

When Nellie was found fit enough to return to duty, she was posted to the Mont Dore Hospital in Bournemouth, arriving on 8 December. During the next three and a half months she was frequently unwell but carried on as best she could.

By the time Nellie’s service at Mont Dore concluded on 28 March 1917, it was clear to RAMC authorities that she was unwell, but exactly what to do with her remained unresolved. After much toing and froing she was posted to the Royal Herbert Hospital in Woolwich, London, and was marched in on 1 May. On 17 September it was recommended that Nellie be granted six months’ leave in Australia. She was informed that the AAMC would arrange passage for her, but this proved more difficult than it should perhaps have been.

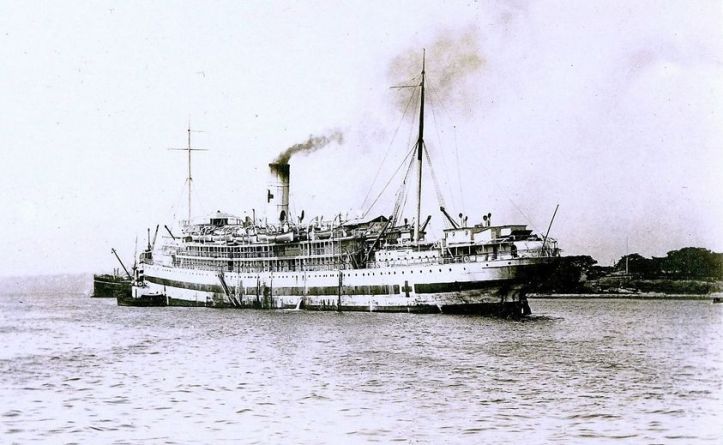

Finally, in December Nellie was offered transport to Australia on a hospital ship, provided that she was willing to undertake light duty during the voyage.

At 2.30pm on 16 December Nellie departed by ambulance train from Southall Station for Avonmouth. She embarked on HMAHS Kanowna and departed for Australia two days later. At least one other Australian nurse was on board, Pearl Goodman of the AANS, who had been working in British hospitals in France when she had fallen ill with tuberculosis. Pearl would later die of the disease.

The Kanowna sailed via the west coast of Africa and by early January 1918 had reached Durban. Here one of the ‘mental patients’ aboard disappeared while the ship was in port. The Kanowna continued on its way and arrived at Fremantle on 5 February 1918. After more than two years away, Nellie was home.

RETURN TO AUSTRALIA

Upon arrival, Nellie was sent to No. 22 Australian Auxiliary Hospital at the Wooroloo Sanatorium, in Wooroloo, around 50 kilometres east of Perth. She was suffering from pulmonary tuberculosis. On 17 March Nellie’s six-month period of sick leave concluded and she resigned from the QAIMNSR. She was now without an income.

Nellie showed no discernible improvement at Wooroloo and her family became dissatisfied with the treatment. She was discharged on 11 May and went home to Albany for three months.

Following the death of her paternal grandfather, Thomas Saw senior, on 31 March that year Nellie had come into a small legacy. In September she travelled to Melbourne with her sister Ethelwynne to seek treatment with Dr. (later Sir) Sidney Sewell at Glenelg Sanatorium in Balwyn. She began her treatment on 21 September.

Before long Nellie’s legacy ran short, and although she still needed months of treatment she could no longer afford it, and was discharged at the end of the year or in early 1919. By now her condition was very serious and she was seen as a “hopeless case.”

After her discharge from Glenelg, Nellie and Ethelwynne remained in Melbourne for a while, staying at Nurse Brazendale’s private nursing home at 100 Hotham Street in East St Kilda. On 9 January 1919, while still there, Nellie filed an application for assistance from the Commonwealth Department of Repatriation. The application was granted on 4 February, and sometime later Nellie and Ethelwynne returned to Western Australia on the Karoola and went home to Albany.

Nellie’s condition continued to deteriorate. She died at 3.30 pm on Monday 31 March 1919 at the Short Street residence of a certain Mrs. Bauditz.

FUNERAL

Nellie was buried with full military honours at the Methodist section of Albany Cemetery on the afternoon of 2 April. Shortly after 3.00 pm that day, the coffin, swathed in the Union Jack, was brought from the house of Thomas and Eliza Saw on Short Street. It was saluted by Chaplain-Captain S. B. Fellows, who escorted it to a hearse and placed on it Nellie’s nursing veil and hood, and her QAIMNSR badge.

The funeral cortege – the Albany Brass Band; the hearse, with the coffin bearers and pall bearers; the chief mourners; a detachment of returned soldiers; a squad of military cadets; naval guards; and a very large number of the general public, including the Mayor – proceeded down Short Street to the Town Hall, and then up York Street towards the cemetery. As the procession moved along, the band played the ‘Dead March’ from ‘Saul.’ Large numbers of people lined the route and many more were at the graveside to pay their last respects. Nellie was interred in the family plot, situated just within the main entrance. At the conclusion of the ceremony the hymn ‘Lead, Kindly Light’ was sung to the accompaniment of the band.

On 6 April a memorial service was held for Nellie in the Wesley Church on Duke Street. It attracted one of the largest congregations seen for some time.

IN MEMORIAM

When Albany’s Avenue of Honour was planted in 1921, the first tree was dedicated to Nellie.

On 17 December 1922, a granite memorial to Nellie was unveiled beside her grave in the cemetery. The following inscription is carved on a polished cross on the eastern face of the monument:

ERECTED

BY THE CITIZENS OF ALBANY

IN LASTING HONOR AND LOVING MEMORY

OF

CHARGE-NURSE NELLIE MABEL SAW

BORN IN ALBANY MARCH 4, 1890

DIED MARCH 31, 1919

HER SERVICE AND LIFE SHE FREELY GAVE

IN NURSING THE SOLDIERS AT THE GREAT WAR

DEATH IS SWALLOWED

UP IN VICTORY

In memory of Nellie.

SOURCES

- Ancestry.

- Ford, H. (2014), ‘A ship’s life – The Kanowna Story,’ 12 June 2014, Australian Stories, Great War Forum.

- The National Archives (UK), ‘Nellie Mabel Saw,’ WO 399/7371.

- The National Archives (UK), ‘Report On The Convalescent Homes For The Nursing Staff In France, 1914 – 1919,’ WO222/2134, via ScarletFinders (website).

- National Archives of Australia.

- Through These Lines (website), ‘Étaples.’

- Wellcome Collection, Royal Army Medical Corps Muniments Collection, ‘Summary of the situation of 26 General Hospital, July 1915-May 1916,’ RAMC/728/2/1.

- Wellcome Collection, Royal Army Medical Corps Muniments Collection, ‘Medical history, transactions, statistics and correspondence, 1916-1917,’ RAMC/728/2/3-7.

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS

- The Albany Advertiser (WA, 30 Oct 1900, p. 2), ‘Advertising.’

- The Albany Advertiser (WA, 28 Oct 1905, p. 2), ‘Advertising.’

- The Albany Advertiser (WA, 18 Feb 1905, p. 4), ‘Children’s Ball.’

- The Albany Advertiser (WA, 16 Dec 1905, p. 3), ‘Albany A. and H. Society.’

- The Albany Advertiser (WA, 23 Dec 1905, p. 4), ‘Albany Show Painting Competition.’

- The Albany Advertiser (WA, 22 Dec 1906, p. 4), ‘Albany Grammar School.’

- The Albany Advertiser (WA, 21 Dec 1907, p. 4), ‘Albany Grammar School.’

- The Albany Advertiser (WA, 18 Nov 1914, p. 3), ‘Under the Red Cross.’

- The Albany Advertiser (WA, 15 Jul 1916, p. 4), ‘“Somewhere in France”: A Nursing Sister’s Impressions.’

- The Albany Advertiser (WA, 5 Apr 1919, p. 3), ‘The Late Nurse Saw: Military Funeral.’

- The Albany Advertiser (WA, 9 Apr 1919, p. 3), ‘The Late Nurse Saw.’

- The Albany Advertiser (WA, 8 Nov 1919, p. 3), ‘Personal.’

- The Albany Advertiser (WA, 20 Dec 1922, p. 3), ‘Nurse Saw Memorial Unveiling Ceremony.’

- The Albany Despatch (WA, 3 Apr 1919, p. 3), ‘Death of Nurse Nellie Saw. Gave Her Life For Her Country.’

- The Albany Mail and King George’s Sound Advertiser (WA, 12 Oct 1887, p. 2), ‘Advertising.’

- Daily News (Perth, 26 Jan 1884, p. 3), ‘Family Notices.’

- Daily News (Perth, 6 Apr 1918, p. 5), ‘Obituary: The Late Mr. Thomas Saw.’

- West Australian (Perth, 3 Apr 1919, p. 4), ‘The Late Nellie Saw.’