AANS │ Lieutenant │ Second World War │ 1st Netherlands Military Hospital Ship Oranje & 2/3rd Australian Hospital Ship Centaur

FAMILY BACKGROUND

Ellen Savage, known as Nell or Nellie, was born on 17 October 1912 in Quirindi, a small town in northeastern New South Wales not far from Tamworth. She was the youngest of three daughters born to Sarah Ann Mulheron (1881–1944) and Henry Savage (1869–1943).

Sarah and Henry were married in 1907 and lived at ‘Glen Rose’ on Nowland Street in Quirindi. Prior to her marriage Sarah had worked as a nurse at Quirindi Cottage Hospital, while Henry was a tailor and kept a shop on George Street in Quirindi. He also dabbled in betting and in 1910 was granted a bookmaker’s licence.

In 1908 Sarah gave birth to the couple’s first child, Winifred Mary, known as Win or Winnie. As an adult Win became a teacher and taught at Quirindi District Rural School.

In 1909 a second daughter, Kathleen, was born. Also known as Kit or Kitty, Kathleen worked in a solicitor’s office before taking up nursing. She, like Nell, would become an army nurse. In 1912 Nell was born.

SCHOOL AND NURSING

Winnie, Kathleen and Nell attended St. Joseph’s Convent School in Quirindi. Nell gained her Qualifying Certificate at the end of 1924 and her Intermediate Certificate at the end of 1927. By then, however, she had transferred to St. Joseph’s Convent School in Werris Creek, 20 kilometres north of Quirindi.

After finishing her schooling, Nell decided to become a nurse and in 1931 was accepted as a trainee at Newcastle Hospital. She passed her final examination in November 1934 and became registered in general nursing on 14 March 1935.

Nell then decided to train in midwifery and gained a place at Crown Street Women’s Hospital in Sydney. At Crown Street Nell met a nurse by the name of Eva King. The two became friends.

Nell gained her midwifery registration on 13 August 1936 but was not going to rest on her laurels. Instead, she undertook infant-welfare training at the Tresillian Mothercraft Training School in Petersham, in Sydney’s inner west, at the completion of which she had become a highly sought-after, triple-certificated nurse. She was subsequently appointed to a position at the Baby Health Centre in Tamworth.

ENLISTMENT

Nell was working at the Baby Health Centre in Tamworth when war broke out in Europe. Like so many of her nursing peers, she wanted to help and in 1941 joined the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS). She was called up for duty and on 24 May enlisted in the Citizen Military Forces (CMF) for home service with the AANS. She was appointed to the rank of staff nurse and posted to Yaralla Military Hospital, also known as the 113th Australian General Hospital (AGH), at Concord in Sydney.

At the 113th AGH Nell saw Eva King again. Eva had also enlisted in the CMF and had been posted to the 113th AGH as a staff nurse. A little later Nell and Eva met Staff Nurse Myrle Moston, who was posted to the 113th AGH on 12 July. Nell, Eva and Myrle would later serve together aboard the Australian hospital ship Centaur.

On 17 November Nell’s and Eva’s appointments to the CMF were terminated upon their secondment the following day to the Second Imperial Australian Force (2nd AIF). They were now eligible for service abroad, but in the meantime they remained at the 113th AGH. On 21 November Staff Nurse Joyce Wyllie from Queensland joined Nell, Eva and Myrle at the 113th AGH. She too would later serve on the Centaur.

1st Netherlands Military Hospital Ship Oranje

On or shortly before 26 January 1942 Nell said goodbye to Eva, who had been attached to the medical staff of the 1st Netherlands Military Hospital Ship Oranje. The Oranje had been loaned to the Australian and New Zealand governments for use as a hospital ship and had already completed two voyages to Egypt to repatriate Australian and New Zealand casualties of the fighting in North Africa. It was due to embark on its third voyage to Suez the following day.

Unfortunately for Nell, Myrle and Joyce, they had not been among those chosen to go. However, Nell at least would join Eva on the Oranje for its fourth and subsequent voyages. On 10 March she was attached to the staff of the ship and departed for Suez two weeks later. Among the other Australian nurses on board, apart from Eva, were Margaret Adams, Cynthia Haultain, Mary McFarlane, Eileen Rutherford, Jenny Walker and Matron Annie Jewell. These eight nurses would later serve together on the Centaur.

Over the next 12 months Nell completed four voyages on the Oranje. The last three were in fact one long voyage, since the nurses were away from Australia for four months, from 6 November 1942 to 1 March 1943. During this time, they sailed to Suez, then to Durban in South Africa, then back to Suez, back to Durban, back to Suez, then to New Zealand and finally home to Australia.

The Centaur

The Oranje’s return to Sydney on 1 March 1943 marked the end of Australian involvement with the ship. Australian medical staff were urgently needed in Australia and New Guinea due to the growing Japanese threat and were withdrawn. However, our eight nurses and many of the male staff of the Oranje were transferred to the Centaur, which had only recently been converted to a hospital ship. It was officially designated 2/3rd AHS Centaur and joined 2/1st AHS Manunda and 2/2nd AHS Wanganella in the service of 2nd AIF troops.

On 17 March Nell and her seven Oranje comrades boarded the Centaur in Sydney Harbour and met the four nurses who would make up the ship’s complement of 12 AANS nurses. As we have seen, Nell and Eva already knew Myrle Moston and Joyce Wyllie, and now they would get to know Alice O’Donnell and Edna Shaw. Four days later the Centaur continued a trial voyage that had begun on 12 March in Melbourne and would conclude on 18 April with the safe return to Brisbane of Australian casualties embarked in Port Moresby.

THE FINAL VOYAGE OF THE CENTAUR

With its capability demonstrated and technical and infrastructural faults corrected, the Centaur was ready to proceed on its first voyage proper.

At 10.45 am on 12 May the Centaur departed Sydney bound once again for New Guinea. The ship’s crew had been tasked with transporting 193 members of the 2/12th Field Ambulance to Port Moresby and then returning with Australian casualties.

Nell was sharing a cabin with Myrle Moston, and Eva was next door. Eva had wanted to be close to her friend, as Nell was a strong swimmer, having learned to swim in the creek behind the hospital in Quirindi, and Eva was not, and they had decided to stick together in the event of trouble.

On the evening of 13 May Matron Annie Jewell celebrated her birthday. The nurses had decorated the dining table with flowers and everything looked very jolly. They had bought a cake in Sydney and now the ship’s cook had iced it in white and written ‘Happy Birthday from the Centaur’ in pink across the top. He served it as part of a special birthday dinner. The evening concluded at around 10.00 pm and Nell and Myrle retired to their cabin.

That night the weather was clear and visibility excellent. The Centaur, travelling unescorted and fully illuminated and marked with the Red Cross, had reached the southern Queensland coast and was in the vicinity of North Stradbroke Island. At 4.10 am, while most of those on board were asleep, a Japanese torpedo slammed into the ship’s hull. The Centaur exploded in a huge ball of fire and sank within three minutes.

There had been no time to launch the lifeboats. Of those who managed to get off the burning ship, some were killed in the water by flying metal, some pulled down by suction, and others burnt by the flaming oil that poured out of the ruptured fuel tanks. In almost the blink of an eye 268 lost their lives. Eleven of Nell’s nursing comrades were killed. Nell survived, along with 63 others.

The 64 survivors clambered onto rafts and bits of wreckage, which they tied together. Nell was seriously injured but concealed this from her fellow survivors. She administered what first aid she could, rationed out food and water, and through her own courage helped to keep morale high. After 34 hours, during which time sharks swam round the rafts, the survivors were rescued by an American destroyer.

Nell’s Story

While recovering in hospital, Nell recounted her experiences, as later quoted by Allan S. Walker, the official Second World War medical historian:

On 13th May I was allotted to Regimental Aid Post duties with Dr Thelander. That afternoon proved to be very busy with many men from the 2/12th Field Ambulance reporting their minor complaints. We were interrupted in our duties by the ship’s siren alerting us to lifeboat drill. That was the fourth for that one day. After being dismissed I dashed to my cabin, and still having many duties to attend to, left my lifebelt on the floor at the side of my bed instead of storing it on top of a wardrobe as usual. The reason I mention this is that it was fateful that the lifejacket should be beside me next morning.

The evening on board ship was as usual and we retired about 10 p.m. Early next morning my cabin mate, Myrle Moston, and myself were awakened by two terrific explosions and practically thrown out of bed. In that instant the ship was in flames. Sister Moston and I were so shocked we did not even speak, but I registered mentally that it was a torpedo explosion. The next thing Sister King, a very great friend, who was in the next cabin screamed near my door “Savage, out on deck.” As we ran together, we tied our lifejackets in place. We were so disciplined that we were making for our lifeboat stations when out on deck we ran into Colonel Manson, our commanding officer, in full dress even to his cap and ‘Mae West’ lifejacket, who kindly said, “That’s right, girlies, jump for it now.” The first words I spoke was to say, “Will I have time to go back for my greatcoat?” as we were only in our pyjamas. He said “No,” and with that climbed the deck and jumped and I followed, hoping that Sister King was doing likewise. There were other people on the deck by then and the ship was commencing to go down. It all happened in three minutes.

I endeavoured to jump as we had been instructed, but the suction was so great I was pulled into the terrific whirlpool with the sinking ship. It would be impossible to describe adequately that ordeal under water as the suction was like a vice, and that is where I sustained my injuries – ribs fractured, fracture of nose and palate by falling debris, eardrums perforated, and multiple bruising. When I was caught in ropes I did not expect to be released. Then all of a sudden, I came up to an oily surface with no sign of a ship, and very breathless from this ordeal.

My first contact was with an orderly, Private Tom Malcolm. We exchanged a few gasped sentences and swam to a piece of flotsam which proved to be the roof of one of the deck houses. We balanced our positions and floated on this till about 8 a.m. There were other people swimming around and scrambling on to whatever was available to hang on to; a few rafts had floated off but not one lifeboat was launched. … I am the only one who survived from the deck where the doctors and sisters were quartered and I never saw Colonel Manson, Sister King or any of the others again. I feel that some would have been concussed in their beds and some would have been endeavouring to dress, but there was no time.

About 8 a.m. we were floating not so far from a raft which was already crowded, but those on board unselfishly decided to make room for us, and a brave lad from Western Australia swam with a piece of rope in his mouth and pulled the raft to us; we stepped across and that is when we saw the first shark, as we had floated away from the oily sea surface. During the day we tied up with other rafts and I suppose about 32 of us floated together surrounded by layers of tiger and grey nurse sharks which frequently shook our rafts. We had two badly burnt men with us, one of whom died that night.

During the 34 hours we were adrift we sighted four ships and several aeroplanes. We would get wildly excited, and, as they passed on their way, an air of despondency would descend on the men. It was a long 34 hours, especially the night time, but morale was very high, and I shall never forget the qualities that were displayed by our Australian seamen and soldiers. The submarine surfaced during the night and that was a terrifying experience. An R.A.A.F. aeroplane eventually sighted us and signalled the U.S. destroyer Mugford, which picked us up (Walker, pp. 462–63).

Nell’s words do not convey the extraordinary bravery and dedication she had shown in the water following the sinking. Despite her own severe injuries, she assisted others, many of whom were severely burned. She swam from raft to raft treating survivors with whatever first-aid items were available. As sharks circled and ships and planes passed by, she raised morale by offering encouragement, leading group prayer and at one point organising a sing-a-long. She also supervised the rationing of food and water.

AFTERMATH

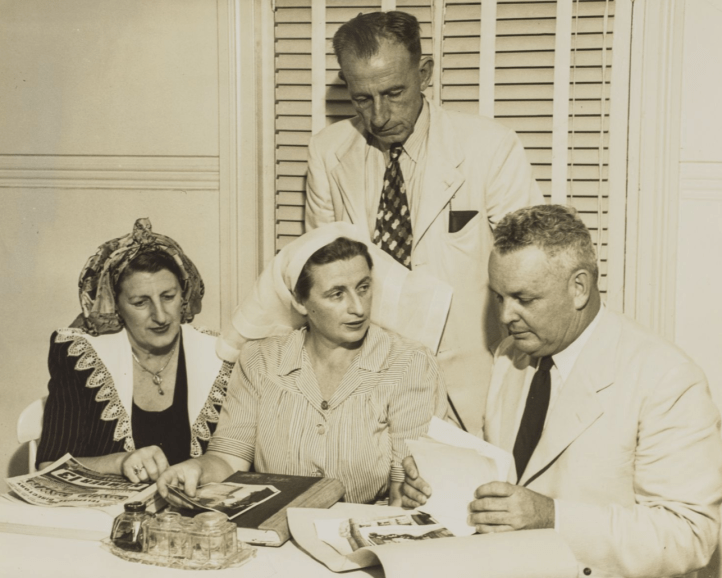

Nell was taken to Brisbane and was visited in hospital by her mother and her sister Kathleen. Nell’s father, who did not visit, later told reporters about how the family was informed of the tragedy. “When the local priest telephoned last Sunday [16 May] that Nellie was in hospital, we thought it was simply seasickness,” he said. “We did not know she was injured as a result of enemy action until yesterday. This was only her second trip on the Centaur, and not being as big a ship as the Oranje, on which she spent two years, she got seasick on her first trip and applied to be moved, but Matron [Jewell] told her that as she was doing a good job she would have to remain.”

On 14 August, having spent three months recovering from her ordeal, Nell resumed her nursing career at the 113th AGH. In December that year Henry Savage died suddenly at a private hospital in Waverley, in Sydney’s eastern suburbs. At the time, he and Sarah were living in Gordon, just north of Sydney. Sarah died in June 1944. Nell, Winnie and Kathleen had lost both parents in less than a year.

Two months after the death of her mother, Nell’s bravery following the sinking of the Centaur was publicly recognised – when, on 18 August, she was awarded the George Medal. She became only the second Australian woman to receive this civilian equivalent of the Victoria Cross. She had been recommended for the award three months earlier by Maj. Gen. S. Roy Burston, whose citation read as follows:

Sister Savage was a member of the nursing staff of 2/3 Aust Hospital ‘Centaur’ when it was sunk on 14 May 1943 as a result of an explosion whilst en route to New Guinea to embark invalids for evacuation to the mainland of Australia. She was the sole survivor of the twelve officers of the AANS on board.

Although suffering from severe injuries received as a result of the explosion, and subsequent immersion in the sea, she displayed great heroism during the period whilst she and some male members of the ship’s staff were floating on a raft, to which they clung for some thirty-four hours before being rescued by an American destroyer.

She rendered conspicuous service whilst on the raft in attending to wounds and burns sustained by other survivors.

Her example of high courage and fortitude did much to maintain the morale of her companions during their ordeal.

NELL’S POST-WAR CAREER

Nell was demobilised in March 1946 and took up an appointment as senior sister at Newcastle Hospital, where she was greatly respected and somewhat feared for her insistence on high standards of discipline and knowledge.

In April 1947, the Florence Nightingale Memorial Committee of Australia (NSW Branch) awarded Nell a Florence Nightingale Scholarship to travel to England to undertake a postgraduate course in hospital administration at the Royal College of Nursing in London. She embarked from Sydney on the Asturias on 28 June, and during her 18-months stay visited several large English hospitals and training schools. In May 1948 she was among Australian guests invited to a presentation party at Buckingham Palace. She also visited Florence and Rome, where she had a private audience with the Pope.

After completing her course in London, Nell travelled to Scandinavia to inspect hospitals and then to Canada to study nursing training. She arrived home from Vancouver on the Aorangi in December 1948. Later she praised the Canadian university schools of nursing, particularly that of Toronto, and stated that much could be done in Australia to improve training methods.

In February 1949 Nell returned to Newcastle Hospital and joined the hospital’s administrative staff.

On 15 May 1949 – six years and a day after the Centaur tragedy – Nell was the first to sign the visitor’s book of the newly opened Centaur House in Brisbane. An appeal launched in 1948 to acquire a building to be used as a residential, recreational, educational and social centre for nurses had raised £53,000, and Exton House had been purchased in central Brisbane and renamed in honour of Nell and her 11 fallen colleagues.

Later in 1949, Nell accepted a Fellowship from the newly formed College of Nursing in New South Wales and would later serve on the college’s council and as president.

In 1950 Nell became matron of Newcastle Hospital’s chest unit at Rankin Park and remained there until 1967, when ill health forced her resignation. She retired to Gordon, where she lived with Win in their late parents’ home at 736 Pacific Highway, before moving to Lane Cove on Sydney’s North Shore.

After attending an Anzac Day reunion on 25 April 1985, Nell collapsed outside Sydney Hospital and later died. She is buried at Northern Suburbs Memorial Gardens.

In memory of Nell.

Sources

- Ancestry.

- Durrant, D. (1998), Quirindi 1939–1950: Courage and Commitment, self-published.

- Milligan, C. and Foley, J. (1993), Australian hospital ship Centaur : the myth of immunity, Nairana Publications.

- National Archives of Australia.

- Pengilley, E. (1983), ‘Community Health Care in the Quirindi District,’ Quirindi and District Historical Society.

- Walker, A. B. (1961), Second World War Official Histories, Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 5 – Medical, Vol. IV – Medical Services of the Royal Australian Navy and Royal Australian Air Force with a section on women in the Army Medical Services (1st edition, 1961), Part III – Women in the Army Medical Services, Chap. 36 – The Australian Army Nursing Service (pp. 428–476), Australian War Memorial.

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS

- The Australasian (Melbourne, 29 May 1943, p. 18), ‘Spotlight on Society: Nurse’s Bravery in Hospital Ship.’

- The Catholic Press (Sydney, 5 Jul 1923, p. 37), ‘Quirindi.’

- The Catholic Press (Sydney, 13 Nov 1924, p. 23), ‘Successful Bazaar and Queen Coronation at Quirindi.’

- Freeman’s Journal (Sydney, 16 Mar 1922, p. 34), ‘Quirindi.’

- The Herald (Melbourne, 19 May 1943, p. 3), ‘12 Centaur Survivors in Melbourne.’

- The Newcastle Sun (NSW, 19 May 1943, p. 2), ‘‘Hall Loose,’ Says Survivor of Centaur.’

- The Sun (Sydney, 23 Jan 1928, p. 2), ‘Intermediate Examination.’

- The Sun (Sydney, 3 Jan 1945, p. 8), ‘A Woman’s Notebook.’