AANS │ Sister Group 2 │ Second World War │ Malaya │ 2/13th Australian General Hospital

Family Background

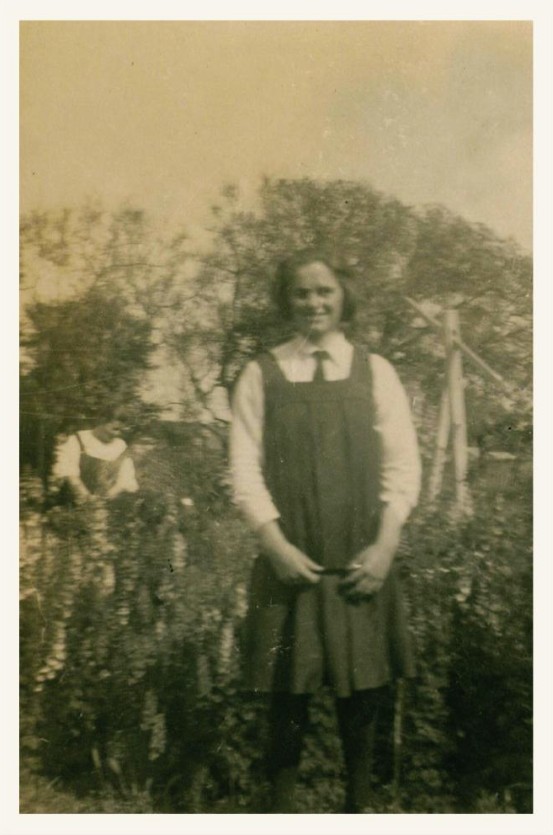

Minnie Ivy Hodgson was born in Leederville, an inner suburb of Perth, on 16 August 1908. She was the fourth of nine children born to Contrary (Connie) Savage (1881–1965) and John William Hodgson (1874–1960).

Connie Savage was born in Vasse, now a suburb of Busselton, in Western Australia. She came from a large family of at least 10 children.

John Hodgson was born in Brighton, England, and migrated to Western Australia in 1899. He departed London aboard the RMS Oruba and on 19 October arrived in Albany. He made his way to Fremantle and on 20 November began working as a turner for the Western Australian Government Railways. His first recorded address was Florence Avenue in Subiaco.

Soon John met Connie and sometime in 1900 they were married in Perth. The following year they moved to Oxford Street in Leederville and Connie gave birth to their first child, Henry John (Harry) Hodgson (1901–1983). In 1902 they moved to West Kimberley Avenue in Leederville.

On 3 April of that same year John’s parents, Rosa Elizabeth Hodgson and William Henry Hodgson; his brother, Henry James Hodgson; and his younger sister, Fanny Emma Hodgson, arrived in Fremantle from London aboard the Oroya. By 1904 they were living on Tate Street in Leederville. (When house numbers were introduced in 1910, theirs was no. 26.)

Connie and John had also moved to Tate Street by 1904, to the future no. 30, next door to John’s parents. In that same year their second child, William James (Bill) Hodgson, was born. In 1905 John finished working for the railways and in 1906 Connie gave birth to another son, Albert Edward Hodgson. Tragically, baby Albert died the next year.

In 1908 the Western Australian government opened up lightly forested land for selection in the area around Lake Yealering, in the south-central Wheatbelt, around 200 kilometres east of Perth. John secured a block and spent the next nine or so years clearing it and building a homestead, travelling to and from Perth. In time he would develop a successful sheep and wheat farm.

In the meantime, in that same year of 1908 Minnie was born, Connie’s and John’s first daughter. The following year, however, saw a loss in the family once again, as John’s mother died.

More children came after Minnie. James Alfred George (Jim) Hodgson was born in 1911, Oliver Shearman Hodgson in 1913 and Fanny Emily Hodgson in 1914. At last Minnie had a sister. Victor Norman Hodgson was born next, in December 1916, but he too died an infant eight months later.

School

All the while, Minnie and her older siblings were attending West Leederville Primary School on Woolwich Street, a 10-minute walk from 30 Tate Street.

By 1917 John had finished clearing his land at Yealering and had built a homestead. He named the property ‘Windstorm’, and the family began to spend time there. In July he advertised in the West Australian for a “smart lad to learn mixed farming good comfortable home.”

On 6 May 1919 another death occurred in the family, when John’s father, William Henry Hodgson, died at home. He was 71 years old. Now Henry Hodgson, John’s brother, took over the running of 26 Tate Street in Leederville.

We do not know exactly when the family moved to ‘Windstorm’ for good. Minnie appears to have spent at least some time at Yealering State School. On the other hand, in 1921 one last child was born to Connie and John in Leederville, Richard Herbert (Dick) Hodgson. Regardless, by 1923 John had either sold or leased the house at 30 Tate Street and the family had moved to Yealering.

In 1923 and 1924, the forthright, strong-willed Minnie boarded at Presbyterian Ladies’ College, in Peppermint Grove, Perth. In 1924 she took exception to one of her reports and complained to the headmistress, Miss Elsie Finlayson. Clearly unsatisfied with Miss Finlayson’s response, Minnie decided to leave school and go home to Yealering. She did not return. Instead, she completed her schooling in 1925 at Methodist Ladies’ College in Claremont. The Hodgson boys meanwhile boarded at nearby Scotch College.

As the 1920s progressed, Minnie involved herself in the Girl Guides movement, and in early 1927 was made a patrol leader. By now John Hodgson was a successful sheep and wheat farmer, and in conjunction with his older sons had expanded his acreage beyond Yealering by taking over leases in the wider district. At the end of the decade, they had 3,300 acres under crop.

Nursing

In July 1928 Minnie, now aged nearly 20, left the area to take up nursing at the Children’s Hospital in Subiaco (which later became the Princess Margaret Hospital for Children). Later that year tragedy struck the family once again when Minnie’s younger brother Oliver drowned on 6 October at the age of 15. He had been rowing with a friend in Freshwater Bay, Swan River, when he lost an oar and dived into the water to retrieve it. He did not make it back to shore.

Minnie returned home to Yealering many times over the next few years. On one memorable occasion she celebrated her 21st birthday. On the evening of 3 August 1929, a ‘Coming of Age’ party was held for her and Miss Elfie Doncon in the 10 Mile Hall, East Wickepin. Around 70 guests enjoyed a dainty supper served on tables beautifully decorated with flowers, after which the young people among them were kept dancing till well after midnight by the Narrogin Jazz Orchestra.

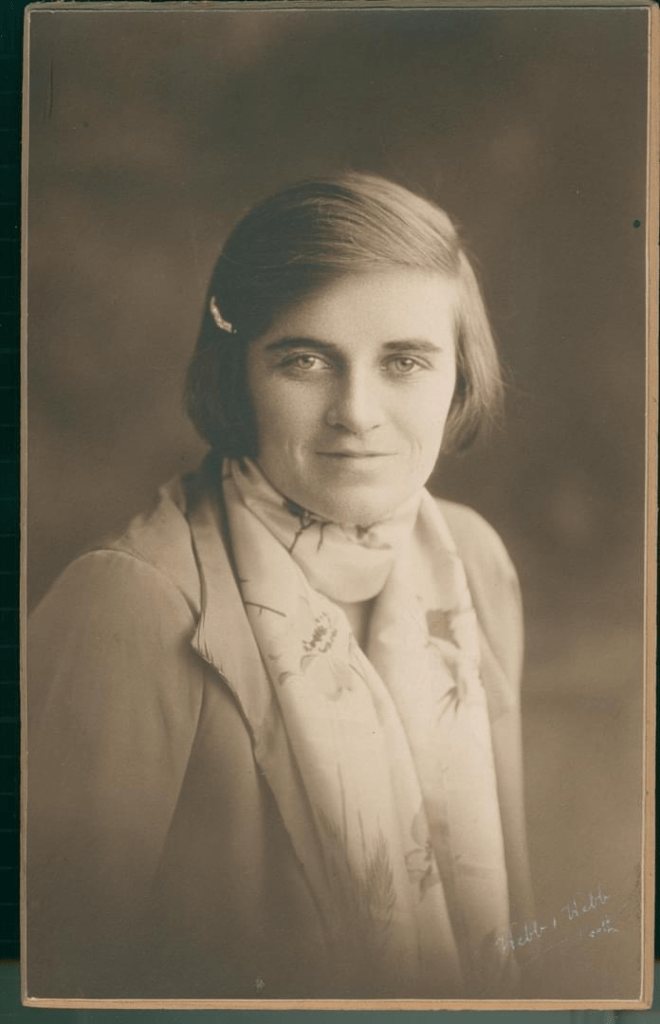

In 1931 Minnie completed her training at the Children’s Hospital and gained her registration in general nursing on 27 November 1931. She then undertook midwifery training at King Edward Memorial Hospital for Women, in Subiaco, and was registered on 24 November 1932.

With her double certification, Minnie had no trouble finding nursing work. In January 1933 she relieved at the Lake Grace Hospital in the eastern Wheatbelt and later in the year took up a position at Greenbushes District Hospital in the South West. In October she acted as sister in charge before resigning in December and returning to Yealering.

In July 1934 Minnie sailed on the MV Kybra from Perth to Carnarvon, 900 kilometres to the north, to take up a nursing position at Carnarvon Hospital, replacing Miss E. Pollard. In 1935 she travelled south again, arriving in June at the Boulder Infant Health Centre in the Goldfields region to relieve Sister Parker for two months. Finally in October 1936 Minnie took up a nursing position at the York Hospital, 100 kilometres northwest of Yealering.

Minnie’s stay in York did not last very long. Two months later, on 10 December, she arrived at the Kondinin District Hospital, located 60 kilometres to the east of Yealering, where she had been appointed matron following the departure of Matron Coffey. Here Minnie would stay for the next two-and-a-half years.

Midway through 1937 Minnie went on sick leave for three weeks, returning in July. Then in September she was granted three months’ leave of absence, which was later described as sick leave. Matron Simpson of Geraldton was temporarily engaged to fill in for her. Minnie returned in December.

Minnie resigned from Kondinin midway through 1939, and on the afternoon of 9 June a large number of her friends and colleagues gathered at the home of Mrs. Deans to bid farewell to her. During the speeches Mrs. S. Gordon on behalf of the Hospital Board and Mrs. MacDonald on behalf of the Hospital Social Committee spoke in glowing terms of the excellent manner in which Minnie had carried out her duties, following which a presentation was made to her.

Enlistment

By now the black clouds of war were rolling over Europe. On 3 September 1939 Prime Minister Robert Menzies announced the beginning of Australia’s involvement on every national and commercial radio station in the country. Thousands of Australians were called up for home service with the Citizen Military Forces (CMF), while others volunteered for overseas service with an expeditionary force, the Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF). Among them was Minnie.

In March 1940 Minnie submitted her application form for service with the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) and then waited. In the meantime, in May she embarked on the MV Koolama for Carnarvon to spend two weeks at the Range Station as the guest of Mrs and Mr Geoffrey Greenway, whom she had perhaps met while working at Carnarvon Hospital in 1934. Then in October she relieved as matron at Wickepin Memorial Hospital when Matron Ingram took her annual leave.

Minnie eventually received word from the Army that she had been accepted. She went to Swan Barracks in Perth on 12 December, had her medical examination, and filled out her Mobilization Attestation Form for home service with the CMF and her Attestation Form for overseas service with the 2nd AIF.

Minnie was not the only one in her family to enlist; her brothers Harry, Bill and Dick all ended up serving during the war – Harry with the CMF in Australia, Bill with the 2nd AIF in the Middle East and New Guinea, and Dick with the 2nd AIF in Australia.

After seven months Minnie received her call up for full-time duty with the CMF and on 14 July 1941 was posted to Northam camp hospital at the rank of Staff Nurse. On 1 August she moved to Narembeen camp hospital and then on 14 August was sent to the 110th Australian General Hospital (AGH), also known as Perth Military Hospital, in Claremont.

The following day Minnie was seconded to the 2nd AIF and appointed to the 2/13th AGH. The 2/13th AGH had been raised in Melbourne in early August for service in Malaya following a request from Colonel Alfred P. Derham, who was both Assistant Director of Medical Services (ADMS) 8th Division, and ADMS 2nd AIF Malaya. In view of intelligence reports suggesting the possibility of a Japanese invasion, Col. Derham had felt that a second military hospital was urgently needed to supplement the 2/10th AGH. This unit, along with the 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station (CCS), the 2/9th Field Ambulance, and other, smaller medical units, had travelled to Malaya in February on the Queen Mary with the 8th Division.

Joining Minnie as 2/13th AGH appointees that day were Sisters Eloise Bales and Vima Bates and Staff Nurses Sara Baldwin-Wiseman, Alma Beard, Iole Harper and Gertrude McManus. They had all been posted to the 110th AGH and most had also been at Northam.

Minnie and her new colleagues remained at the 110th AGH for the next 10 days and were then granted pre-embarkation leave. During her leave, Minnie returned home to Yealering. It would be the last time.

Two days before their embarkation and three days before their departure, the seven nurses were guests of honour at a farewell morning tea arranged by the Sportsmen’s Organising Council for Patriotic Funds and held at the Hotel Adelphi in Perth. Each of the seven was presented with an initialled rug by Lieutenant-Governor Sir James Mitchell. Premier Willcock, who was also at the function, said that the nurses “go expecting the best but prepared to take the worst.” Five other AANS nurses, Frances Aldom, Betty Brooking, Mary Hardwick, Beanie Keamy and Gwen Martin, were also guests at the tea, along with Matron M. D. Edis, Principal Matron (Western Command), who thanked the Sportsmen’s Council for arranging the function.

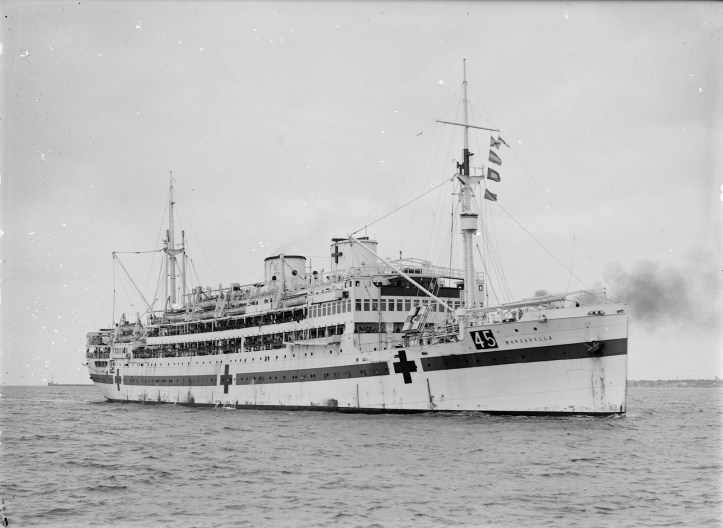

2/2nd AHS Wanganella

On Monday 8 September Minnie, Vima, Sara, Eloise, Alma, Iole and Gertrude travelled to Fremantle and prepared to board the 2/2nd Australian Hospital Ship Wanganella, which had arrived that day. The ship, formerly a passenger liner, had been converted into a hospital ship in May and commissioned in July. It had left Sydney on 29 August with a contingent of 2/13th AGH personnel from New South Wales and Queensland that included 19 AANS nurses. Then in Melbourne the main body of the 2/13th AGH had boarded – 24 Victorian, South Australian and Tasmanian AANS nurses and around 180 other personnel.

As Monday became Tuesday the Wanganella was still tied up at harbour. Minnie was becoming restless. She penned a letter to her friend Norma. “We’ve been sitting here for two days,” she wrote, “waiting to be taken off onto the boats & it’s becoming somewhat tedious, we’ve been packed and locked for two days. Yesterday it was too rough & today I think we really will go, they say to Singapore, Malaya, Darwin, Bombay & other places so heaven knows where we’ll go. I don’t care much as long as we get it over.”

Finally, later that day, the Wanganella pulled out of Fremantle’s inner harbour, sailed past the Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth, which were carrying troops bound for the Middle East, and headed in a northerly direction over a very placid Indian Ocean. Shortly afterwards those on board were officially told that they were bound for Malaya.

On board, the nurses spent their time demonstrating bandaging and other basic nursing procedures to the unit’s orderlies. They attended lectures on tropical medicine and ran their own sick bay on a roster system. Unlike their peers on the Queen Mary, they did not have to staff an onboard hospital or dressing station: the other members of the 2/13th AGH took care of that. For half an hour each morning they practised using their gas masks and tin helmets. During leisure time they played quoits on deck and enjoyed the other entertainments on board. Minnie’s Western Australian colleague Iole Harper was horribly seasick and spent most of her time on her bunk.

Singapore

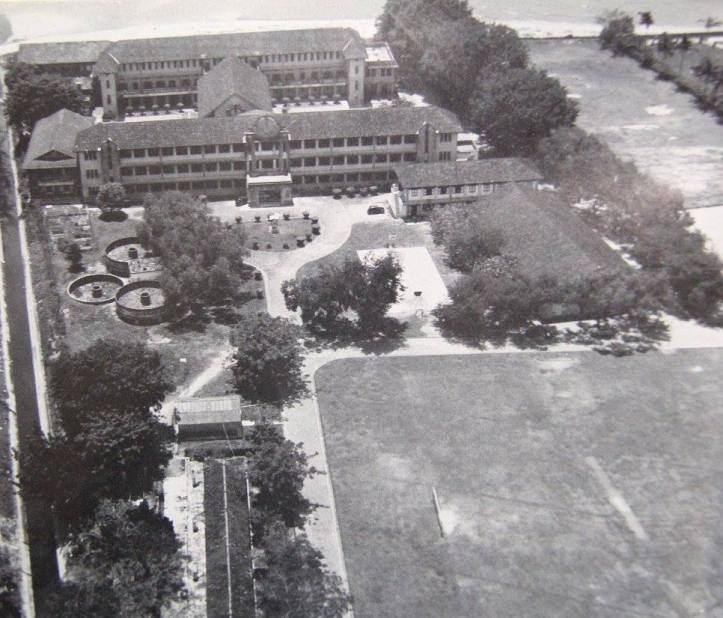

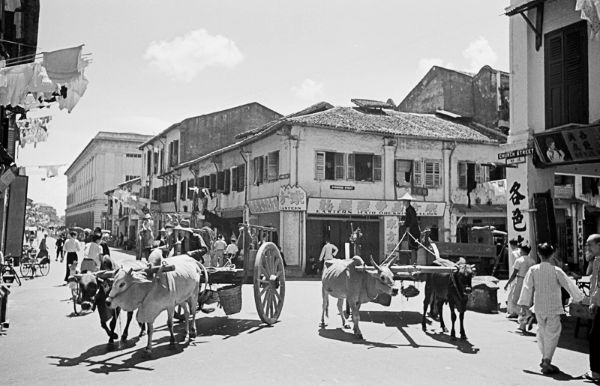

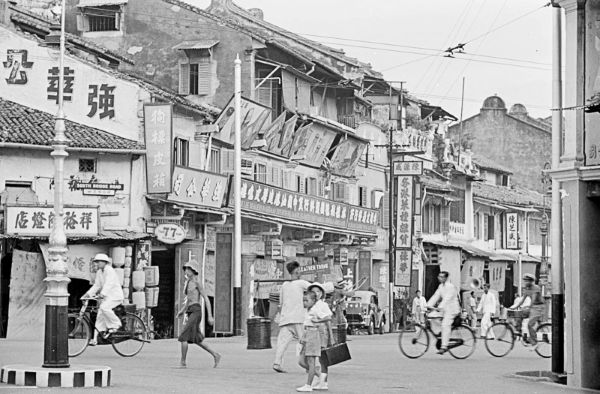

On 15 September the Wanganella arrived at Keppel Harbour on Singapore Island and berthed at Victoria Dock. Ten of the 2/13th AGH nurses were immediately detached to the 2/10th AGH and did not disembark with their colleagues. They later entrained for Malacca, somewhat dismayed at being so suddenly separated from their new friends. Minnie and the others, meanwhile, disembarked and in sweltering heat set off in buses for St. Patrick’s School, located in Katong on the south coast of the island just to the east of Singapore city. Here the unit would be based until such time as its permanent home, an unfinished psychiatric hospital in Tampoi, in the south of the Malay Peninsula, was ready for their occupation.

St. Patrick’s was a requisitioned Roman Catholic boys’ school comprising several large, brick buildings set in extensive grounds. On its southern boundary the school was separated from Singapore Strait by barbed wire, landmines and notices that read ‘Danger – Keep Away’. The nurses were allocated pleasant quarters in the south wing of the school with wide balconies and views over the beach. They slept on rope mattresses under mosquito nets, and it took some time to grow accustomed to the heat and humidity.

For some of the newly arrived nurses, Singapore was something of a shock to the system. The sights, sounds, smells and customs were all unfamiliar. Some of the nurses for instance thought that those locals who chewed and spat out betel nut had tuberculosis and therefore were to be avoided. Other nurses were challenged by the practice of bartering. They soon learned how to bargain, however, and shopping became a most enjoyable exercise. Those nurses who began by exploring on foot soon learned that they were expected instead to catch taxis, since “European ladies never walk anywhere.” There was then the challenge of how to pay for taxis when the nurses earned only eight shillings a day, the same as a Private.

On 6 October the 10 nurses detached to the 2/10th AGH returned to St. Patrick’s. They had gained valuable experience in tropical nursing with their peers in Malacca and were now able to pass it on to the orderlies and stretcher bearers of the 2/13th AGH. That same day the next contingent of 2/13th AGH nurses, 21 in all, was detached to the 2/10th AGH – among them Minnie, Gertrude McManus and Sara Baldwin-Wiseman. They arrived at Malacca the following day.

The 2/10th AGH had established its hospital in several wings of Malacca’s Colonial Service Hospital and, together with the 2/4th CCS, the 2/9th Field Ambulance and the other Australian medical units, was responsible for looking after nearly 6,000 8th Division troops. The nurses treated tropical infections, such as tinea and ‘Singapore’ ear; tropical diseases, such as malaria; and injuries resulting from training and other accidents. They also assisted with routine operations. They were busy but not overworked, and, as in Singapore, there was plenty of time for such off-duty activities as shopping, tennis, swimming and golf, dinners and dancing, picnics, drives etc.

After just over three weeks at Malacca, Minnie, Sara, Gertrude and the others rejoined the 2/13th AGH on 29 October, and the next contingent entrained northwards. Other 2/13th AGH nurses had by now been detached to the 2/4th CCS, which at the end of September had moved south and established a small hospital of 150–200 beds in the same psychiatric hospital at Tampoi earmarked for the 2/13th AGH. At the same time, several of the unit’s (male) nursing orderlies and theatre assistants had also gone to train at the 2/4th CCS.

On 20 November Minnie was again detached to the 2/10th AGH. When she returned to her unit on 13 December, the 2/13th AGH had finally moved into the psychiatric hospital at Tampoi, and Japan had invaded Malaya. The Pacific War had begun.

Japanese Invasion

Soon after midnight on 8 December, a force of some 5,000 troops of the Imperial Japanese Army had launched an amphibious assault at Kota Bharu on the Malay Peninsula’s northern coast. Four hours later, 17 Japanese bombers attacked Singapore Island. From Tampoi, some of Minnie’s colleagues heard the bombing in the distance and saw searchlights and the silver trails of tracer bullets firing vainly at Japanese aircraft overhead.

From their beachhead at Kota Bharu, the well-trained, combat-ready Japanese forces, backed by mechanized units and substantial sea and air power, began to press southwards, forcing severely outgunned British and Indian troops to retreat before them. Within six days, two more Japanese forces had crossed into northern Malaya from Thailand.

The day before Minnie’s return, the unit received a memo from Lieutenant Colonel J. G. Glyn White, Deputy Assistant Director of Medical Services (ADMS), 8th Division, ordering the hospital to expand from 600 to 1,200 beds, and by 15 December two new wards had been set up. Staff were also required from then on to wear Red Cross armbands, and the nurses were no longer allowed outside the hospital compound after dark, nor were they allowed visitors.

The war became hotter and closer, Minnie and her colleagues quickly became used to interrupted sleep, blackouts and air-raid warnings. Some of the nurses were formed into a signals squad, whose job it was to ring a large brass bell upon receiving the message ‘Air Raid Red’ from the Army Signals Corps, whereupon the nurses and their amahs (housemaids) would head for the cover of the jungle. Others formed a decontamination squad.

Christmas came as a welcome distraction. The wards at Tampoi were decorated, and the patients’ rations were boosted for the festive event. The officers helped to carve the poultry and ham and helped the nurses to serve the bed patients. They also made the nurses sit down with the up patients and waited on them. In return the nurses arranged a party in their mess for the officers and on Boxing Day a larger party for the troops. Minnie received a Christmas parcel from the Yealering RSL and wrote a letter of acknowledgement and thanks, which arrived in late January 1942.

Events sped up after Christmas. In the face of Japan’s unstoppable push southwards, it became clear that the 2/10th AGH at Malacca would have to evacuate to Singapore Island, and staff and patients were moved south in stages. Between 29 December and 5 January 1942, 36 nurses and around 40 other staff joined Minnie at the 2/13th AGH, bringing scores of patients with them. Twenty more were detached to the 2/4th CCS, which had moved from Tampoi to Mengkibol Estate, near Kluang. By 15 January the 2/10th AGH had completed its move to Oldham Hall and Manor House at Bukit Timah on the island, and by 17 January most detached nurses had rejoined the unit.

On the evening of 16 January, the war hit the 2/13th AGH hard. Two days previously, Australian troops had entered combat for the first time, and after achieving a tactical victory against a Japanese force at Gemas, fought much bloodier battles over the following two days. Soon, convoys of casualties on stretchers with tickets pinned to them showing the most urgent injuries began to flow to Tampoi via the 2/4th CCS. The admission room quickly established identity, rank and injury, then stretcher bearers ran the wounded to either a ward or an operating theatre. The unit had worked hard to prepare operating theatres to receive them and had by now very nearly fulfilled the 1,200-bed stipulation.

Retreat to Singapore

On 21 January, Lieutenant Colonel Glyn White, in consultation with Colonels Edward Rowden White and Douglas Clelland Pigdon, commanding officers of the 2/10th and 2/13th AGHs respectively, instructed the 2/13th AGH to evacuate to Singapore Island. After some discussion it was decided to return to St. Patrick’s School, and a handful of Minnie’s colleagues were sent there to clean and prepare it for the unit’s arrival. Abandoned bungalows adjoining the school were cleaned in preparation for their use as staff quarters.

The relocation took place over the weekend of 24–25 January. The final convoy, carrying medical patients, arrived late on Sunday night. Matron Irene Drummond had ensured that beds had been made, pyjamas and towels placed at the ready, cold drinks and sandwiches prepared, and teapots warmed up. By midnight all patients were safely bedded down. The move had been a startling success.

On 28 January the 2/4th CCS followed the other two medical units to Singapore Island, relocating to Bukit Panjang English School. Two days later the final Commonwealth troops crossed the Causeway from the Malay Peninsula to Singapore Island, and the next morning it was blown up. Within a little more than a fortnight, Singapore would fall.

Japanese troops reached the northern shore of Johor Strait soon after the demolition of the Causeway and began a ferocious artillery bombardment of the island. They crossed the strait on the night of 8 February and by the morning had established a beachhead on the northwestern corner of Singapore island, despite strong opposition from Australian troops.

Minnie and her colleagues were now working under extreme pressure. With convoys of ambulances arriving at St. Patrick’s with hundreds of wounded soldiers, the hospital became so overcrowded that outbuildings and even tents were used as wards. Casualties lay closely packed on mattresses on floors and even outside on the lawns, the majority with gunshot and shrapnel wounds. The nurses worked 12-hour shifts, and the theatre, blood bank and x-ray nurses worked even longer. When they did eventually finish their shifts, the constant air-raids, bombings and artillery barrages made sleep hard to come by.

Evacuation of the Nurses

With Singapore’s fate all but certain, a decision was made to evacuate the nurses. Already in January, following reports of Japanese atrocities in Hong Kong, Col. Derham had asked Major General H. Gordon Bennett, commanding officer of the 8th Division in Malaya, to evacuate the AANS nurses. Bennett had refused, citing the damaging effect on morale. Colonel Derham then instructed Lieutenant Colonel Glyn White to send as many nurses as he could with Australian casualties leaving Singapore.

On 10 February, six 2/10th AGH nurses embarked with 300 wounded on the hospital ship Wusueh. The following day, Minnie and the other 2/13th AGH nurses were summoned into their mess and told that they were all to be evacuated when ships were available. That afternoon, the entire staff was assembled when ambulances arrived to transport the departing nurses to Keppel Harbour. However, it turned out that now only 30 were to leave, and Matron Drummond read out their names. They were requested to go quietly with no good-byes. They were to pack just one small suitcase and take respirators and ‘iron rations’ with them. And they had no option of either staying with the patients or waiting until all of the staff could leave together. They had to go. They eventually departed on the Empire Star very early the next morning alongside a similar number of their 2/10th AGH peers.

Now 65 AANS nurses remained in Singapore, of whom 26 belonged to the 2/13th AGH, among them Minnie, Vima Bates, Alma Beard and Iole Harper. The other three Western Australian nurses, Sara Baldwin-Wiseman, Eloise Bales and Gertrude McManus, had left aboard the Empire Star. They were the lucky ones.

Late in the afternoon of 12 February, the 27 remaining 2/13th AGH nurses and four nurses of the 2/4th CCS were taken by ambulance from St. Patrick’s to St. Andrew’s Cathedral in Singapore city, which by then had been converted into a makeshift hospital. Here the nurses met up with the remaining 2/10th AGH and 2/4th CCS nurses. The ambulances then continued to Keppel Harbour until they could drive no further, at which point the nurses got out and walked the remaining few hundred metres. The harbour was shambolic. Fires burned as women and children ran everywhere trying to get on boats. Dozens of cars had been dumped in the harbour, and from the water protruded the masts of sunken ships. While the nurses were waiting, two bombs fell not far away.

Vyner Brooke

Eventually Minnie and her 64 comrades were ferried out to the Vyner Brooke, a small coastal steamer and one-time pleasure craft of colonial nabob Sir Charles Vyner Brooke. On board there were as many as 150 people – women, children, old and infirm men. In the gathering darkness the ship slipped out of Keppel Harbour and, after lengthy delays, began its journey south. Behind the Vyner Brooke, the city was burning, and a pall of thick, black smoke hung in the sky.

That night the Vyner Brooke made little progress and spent much of Friday hiding among the hundreds of small islands that line the passage between Singapore and Batavia. Matrons Paschke and Drummond took the opportunity to work out a plan of action in the event of a Japanese attack. The nurses were assigned to particular areas of the ship and would offer first aid and assist passengers into the lifeboats.

By the morning of Saturday 14 February, Captain Richard Borton was approaching the entrance to Bangka Strait. To the right lay Sumatra; to the left, Bangka Island. Suddenly, at around 11.00 am, a Japanese plane swooped over, then flew off again. At around 2.00 pm another plane approached before flying off. The captain, anticipating the imminent arrival of Japanese dive-bombers, sounded the ship’s siren and began a run through open water. When a squadron of dive-bombers appeared on the horizon, Borton commenced evasive manoeuvres.

As the bombers approached, the Vyner Brooke zigzagged wildly at full speed. The first wave of bombs missed the ship. The planes banked, lined up again, and came in for a second run. This time there was no escape. A bomb struck the forward deck, killing a gun crew. Another entered the ship’s funnel and exploded in the engine room. The Vyner Brooke lifted and rocked with a vast roar. A third bomb tore a hole in the side of the ship. The Vyner Brooke listed to starboard and began to sink, 15 kilometres from Bangka Island.

After the first explosion, the nurses hurried about the deck carrying out the tasks assigned to them. They were carrying morphia and dressings in their pockets and administered first aid to wounded passengers, including their own colleagues, and helped them to the three remaining lifeboats. Once every passenger was off the ship Matron Paschke permitted the nurses to leave. Those who had been injured, and some of those who could not swim, had left in the lifeboats. The others removed their shoes and tin helmets and entered the water any way they could. Some jumped from the railing on the portside, others practically stepped into the water on the listing starboard side, and still others slid down ropes or climbed down ladders. All were wearing lifebelts made of cork and canvas so were at least able to float.

Bangka Island

Minnie may have clambered into a lifeboat or perhaps trailed behind one, holding on to a grabrope, as a number of nurses did. Or perhaps she clung to a raft or a piece of wreckage, or simply floated in her lifebelt. Regardless, she made it ashore in the vicinity of Radji Beach and joined a growing group of survivors, including 21 of her colleagues, around a bonfire.

Saturday night passed, and on Sunday the survivors learned that Bangka Island had come under Japanese occupation. The idea of surrender to Japanese authorities was floated as a viable option but it was agreed to wait until the following morning before deciding.

Early in the morning of Monday 16 February, another lifeboat and several life rafts came ashore carrying British soldiers and sailors. There were now more than 100 people on the beach. Now it was decided to surrender to Japanese authorities, and a deputation left for the nearest large town, Muntok, to negotiate this. A short while later most of the group’s civilian women and children followed behind.

Around mid-morning the deputation returned with Japanese officers and soldiers. The soldiers separated the survivors into three groups: the officers and NCOs, the servicemen and male civilians, and the AANS nurses and at least one civilian woman. They took the first two groups in turn around a nearby headland and murdered them, bayoneting the first and machine-gunning the second.

The Japanese soldiers returned to the women and ordered them to line up on the beach with their faces to the sea, even those who were injured.

The women began to walk into the water, and the soldiers opened fire. Minnie died alongside 20 of her comrades. Miraculously, Staff Nurse Vivian Bullwinkel of the 2/13th AGH survived.

Aftermath

For the next two-and-a-half years, Minnie’s family had no idea of what had happened to her, other than that she had been reported missing by the Army. Then in mid-1944 Minnie and the other 20 nurses killed on Bangka Island, as well as those 12 nurses who were lost at sea following the bombing of the Vyner Brooke, were reported as missing believed killed. On 1 July 1944 the matron-in-chief of the 2nd AIF, Annie M. Sage, wrote a letter to Minnie’s parents.

Dear Mr. Hodgson,

I was very grieved to learn the latest information conveyed to you regarding your daughter, Minnie.

I realise the strain of the past two and a half years and the shock of the news that we can no longer hope for her return.

Every member of the A.A.N.S. pays tribute to her outstanding bravery and devotion to duty.

May I, on behalf of the Sisters in the Army, offer their deepest sympathy and assure you of their desire to make the Service worthy of such gallant members.

Yours sincerely,

Annie M. Sage.

However, it was not until the rescue in September 1945 of the surviving 24 nurses – of the 32 who had survived both the sinking of the Vyner Brooke and the massacre on Radji Beach, eight had died in prison camps on Sumatra and Bangka Island – that Minnie’s family finally learned definitively of her terrible fate.

In memoriam

Minnie’s name is recorded on the Singapore Memorial and at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. In 1954 her name was recorded on the Yealering Memorial Gates. In 2022 a mural of Minnie was unveiled at the Kondinin Memorial Garden. In 2023 a community park in West Leederville, close to Minnie’s childhood home, was renamed Minnie Hodgson Park in her honour. And in the very near future she and Alma Beard may have an electorate in Western Australia named in their honour.

We will not forget her.

Sources

- Ancestry.

- Arthurson, L., ‘The Story of the 13th Australian General Hospital, 8th Division AIF, Malaya,’ presented by Peter Winstanley (2009).

- Australian War Memorial, ‘Iole Burkitt (Harper) as a staff nurse 2/13th Australian General Hospital and a prisoner of the Japanese, 1942–1945, interviewed by Jane Fleming (1983–84).’

- Crouch, J. (1989), One Life Is Ours: The Story of Ada Joyce Bridge, Nightingale Committee, St. Luke’s Hospital.

- Dietsch, J. (10 Nov 2022), ‘Never-before-seen photos of heroic nurse Minnie Hodgson revealed.’ PerthNow.

- Find My Past.

- Goossens, R., SS Maritime (website), ‘Wanganella: The History and Story of a Very Special Ship.’

- Jeffrey, B. (1954), White Coolies, Angus & Robertson.

- Long, G. (1962), Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 5 – Medical, Vol. II – Middle East and Far East, Part II, Chap. 23 – Malayan Campaign (pp. 492–522), Australian War Memorial.

- The Long and Winding Road (website), ‘Singapore in 1941 from the Harrison Forman Collection’ (17 Apr 2020).

- National Archives of Australia.

- Peirce, A. F. (7 May 2023), The Curb, ‘The War Nurses author Anthea Hodgson talks about bringing lost stories of Perth’s nurses to life in this interview.’

- Presbyterian Ladies’ College Perth, Blackwatch (Winter 2017), ‘From the Archives.’

- Shire of Wickepin (20 April 2020), ‘Stories Commemorating Our Local War Heroes Taken from Fallen but Not Forgotten by Stefanie Green 2018.’

- State Library of Western Australia, ‘55/15/21: WA Post Office Directory Map of Perth, Fremantle & suburbs, 1900.’

- State Library of Western Australia, Western Australia Directory, 1893–1949.

- Town of Cambridge (19 April 2023), ‘Tribute to World War II Nurse Unveiled in West Leederville.’

- University of NSW, Canberra, Australians at War Film Archive, ‘Loris Church (Kitch).’

- WA Military Digital Library.

Sources: Newspapers

- The Albany Advertiser (21 Oct 1899, p. 3), ‘Shipping Intelligence. Arrivals.’

- Corrigin Chronicle and Kunjin-Bullaring Representative (5 Jul 1928, p. 3), ‘Yealering.’

- Corrigin Chronicle and Kunjin-Bullaring Representative (20 Aug 1936, p. 2), ‘Yealering.’

- Corrigin Chronicle and Kunjin-Bullaring Representative (24 Jan 1942, p. 4), ‘R.S.L. Notes.’

- The Daily News (Perth, 26 Apr 1927, p. eight), ‘The Broadcast Listener.’

- Great Southern Leader (Pingelly, 28 May 1926, p. 4), ‘Advertising.’

- Kondinin-Kulin Kourier and Karlgarin Advocate (10 Dec 1936, p. 2), ‘Personal and Social.’

- Kondinin-Kulin Kourier and Karlgarin Advocate (9 Sep 1937, p. 3), ‘Personal and Social.’

- Kondinin-Kulin Kourier and Karlgarin Advocate (15 Jun 1939, p. 2), ‘Local and General.’

- Kulin Advocate and Dudinin-Jitarning Harrismith Recorder (20 Jun 1935, p. 3), ‘Yealering.’

- Kulin Advocate and Dudinin-Jitarning Harrismith Recorder (Thu 6 Oct 1938, p. 3), ‘1938 Show.’

- Manjimup Mail and Jardee-Pemberton-Northcliffe Press (21 Nov 1930, p. 1), ‘Personal.’

- The Narrogin Observer (10 Nov 1928), p. 6), ‘Yealering.’

- The Narrogin Observer (14 Dec 1929, p. 3), ‘Yealering.’

- The Narrogin Observer (4 Apr 1931, p. 4), ‘Yealering.’

- The Narrogin Observer (14 Nov 1931, p. 4), ‘Yealering.’

- The Narrogin Observer (3 Oct 1936, p. eight), ‘Yealering.’

- The Narrogin Observer (12 Oct 1940, p. 6), ‘Wickepin.’

- The Narrogin Observer (13 Sep 1941, p. 6), ‘Yealering.’

- Northern Times (Carnarvon, 1 Aug 1934, p. 2), ‘Personal & Social’.

- Northern Times (Carnarvon, 24 May 1940, p. 3), ‘Personal’.

- Northern Times (Carnarvon, 15 May 1941, p. 3), ‘Social and General.’

- Northern Times (Carnarvon, 22 May 1941, p. 3), ‘Port Hedland.’

- The West Australian (Perth, 4 Jul 1917, p. 10), ‘Advertising.’

- The West Australian (Perth, 17 Oct 1928, p. 1), ‘Family Notices.’

- The West Australian (Perth, 31 Oct 1928, p. 18), ‘College Boy Drowned.’

- The West Australian (Perth, 26 Dec 1933, p. 12), ‘Country News.’

- The West Australian (Perth, 17 Feb 1938, p. 4), ‘Engagements.’

- Western Mail (Perth, 16 May 1919, p. 27), ‘Family Notices.’

- Wickepin Argus (15 Aug 1929, p. 2), ‘Yealering.’

- Wickepin Argus (12 Jan 1933, p. 2), ‘Yealering.’

- Wickepin Argus (4 Jan 1934, p. 2), ‘Yealering.’

- Wickepin Argus (5 Jul 1934, p. 2), ‘Yealering.’

- Wickepin Argus (19 Jul 1934, p. 2), ‘Yealering.’