AANS │ Lieutenant │ Second World War │ Malaya │ 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station

FAMILY BACKGROUND

Wilhelmina Rosalie Raymont, known as Willie and Mina and later Ray, was born on 7 December 1911 in Adelaide. She was the daughter of Laura Rosalie Newman (1878–1971) and William Ernest Raymont (1875–1916).

Laura Newman was born in Adelaide to Celia Maria Richards from Montacute in the Adelaide Hills and Albert Johann Gotthilf Neumann from Crossen an der Oder in Prussia (now part of Poland). Albert migrated to Australia in 1864 with his father and two siblings. By the time he married Celia Richards in 1872, he had Anglicised his surname to Newman. Celia and he had five children, all of whom, apart from Laura, died before the age of two. On 8 April 1889, while the Newmans were living on Edward Street in Norwood, Albert drowned at Port Adelaide, aged only 39 years.

William Raymont was born in Angle Vale, near Gawler in South Australia. He was one of seven children born to Mary Bridgeman and the Rev. John Raymont, who had arrived at Port Adelaide in late 1874 from Devon, England. John Raymont became a widely respected Methodist minister and preacher and was in great demand to officiate at weddings, while Mary taught Sunday school.

Laura and William were married on 4 October 1900 at the residence of Mrs. Richards of Kent Town in Adelaide, who was likely one of Laura’s aunts. They settled at ‘Restholme’ on Percy Street, Semaphore, a beachside suburb of Adelaide, and began their family the following year. Mary Elizabeth, known as Molly (1901–1990), was the first to be born. Then came John Albert (1903–1976), Laura Maude, known as Judy (1905–1935), William Devon (1907–1960) and Florence Mabel, known as Mab (1909–2002). Wilhelmina – or Mina – came next, followed by Nancy (1913–2000).

MINA’S FATHER SERVES AT GALLIPOLI

On 9 September 1914 William Raymont enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF). At the time he was living apart from Laura and working as a clerk at the Islington Railway Workshops in the northern suburbs of Adelaide. He was attached to the 10th Infantry Battalion, 1st Reinforcements as a private and embarked for Egypt on 21 December. Laura was left to look after seven children, with another one on the way. Little Peggy Alexandra Stewart was born on 10 April 1915.

Exactly one month later, after fighting at Anzac Cove, William was admitted to the 1st Casualty Clearing Station (CCS) with a poisoned hand and teeth. He was then transferred to Egypt to convalesce at Helouan and in June was assigned office duties at Zeitoun.

On 16 June William was admitted to the 1st Australian General Hospital (AGH) at Heliopolis with a recurrence of symptoms associated with a previously diagnosed duodenal ulcer. He was found unfit for service and on 29 July embarked for Australia from Suez, arriving in Melbourne on 25 August.

FAMILY TRAGEDY

After returning to Adelaide, clearly unwell, William was admitted to the 7th AGH at Keswick. The Army Medical Board found that he was suffering from “delusional insanity” exacerbated by active service, and he remained in hospital until January 1916. Little Peggy died while he was there, on 5 November. She was only seven months old.

William was discharged from the Army on 2 May 1916 and in mid-June resumed his work at the railway workshops in Islington. Less than two weeks later, on 29 June, he died at the family home on Percy Street, reportedly of heart failure. A military cortege accompanied his coffin from the house to Cheltenham Cemetery. At the time Mina was just four-and-a-half years old.

Laura Raymont had lost her father, four siblings, her youngest child and now her husband. By September 1918 she had moved her family to 11 Parr Street in Largs Bay, a suburb adjacent to Semaphore, and had taken up music teaching as a source of income. (As a teenager she had studied pianoforte and music theory under Mr. W. Lyons.) She also advertised in the ‘Wanted’ columns of the newspapers for a front room on the Esplanade in Semaphore, perhaps from which to teach music.

By now Mina was nearly seven years old and most likely going to school. However, details of her childhood and early adulthood are scarce.

On April 1926 Mina’s maternal grandmother, Celia Newman, died while living with the Raymonts on Parr Street. She was 75 years old. More sadness followed in April 1935 with the death of Laura (otherwise known as Judy), Mina’s second eldest sister, who died of septicaemia under tragic circumstances. She was 29.

NURSING AND ENLISTMENT

In the 1930s Mina decided to become a nurse. She trained at the Waikerie Hospital, situated on the Murray River in South Australia’s Riverland region, and at the Adelaide Hospital. In October 1936 she passed her final examination.

After completing her training, Mina moved to Tasmania, where for a time she nursed businessman turned politician Charles William Grant at High Peak, his sprawling residence in Fern Tree on the outskirts of Hobart.

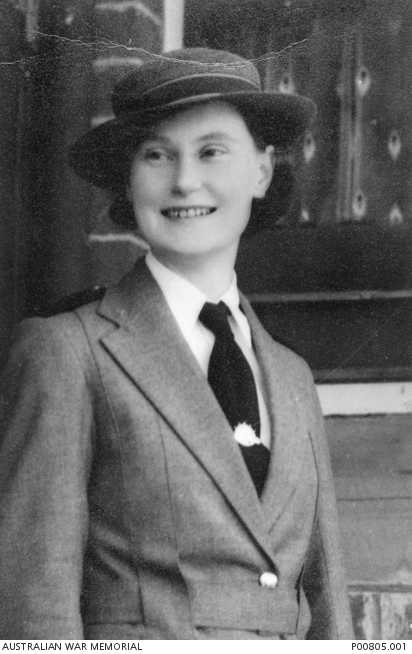

Australia was now at war, and Mina wanted to serve. She joined the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) and on 4 September 1940 completed her attestation form for service abroad with the 2nd Australian Imperial Force (AIF). At the time she was living at 266 Davey Street in Hobart. Two of her brothers had already joined Australia’s fighting forces. John had been accepted into the RAAF in July 1940, while William had joined the RAN in 1937.

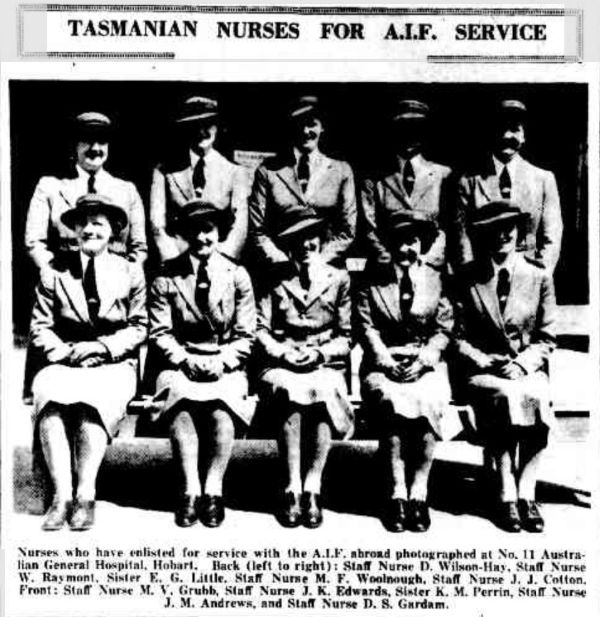

While Mina awaited to be called up for service with the 2nd AIF, she was posted to the 111th Australian General Hospital (AGH), based at the Royal Hobart Hospital. In November she was photographed with other Tasmanian AANS nurses at the 111th AGH. Most would end up serving with the 2/7th AGH in the Middle East, but one, Staff Nurse Shirley Gardam, would serve with Mina in Malaya.

On 16 December Mina was taken on strength of the AANS, 6th Military District (Tasmania) at the rank of staff nurse and on 10 January 1941 was detached to a new 2nd AIF medical unit, the 2/4th CCS. She was marched in the same day.

The 2/4th CCS, based at Brighton Army Camp, 25 kilometres north of Hobart, was being raised for service in Malaya under the command of Lt. Colonel Tom Hamilton, a Newcastle surgeon. As casualty clearing stations are the closest medical units with surgical facilities to the front line, Lt. Colonel Hamilton was looking for nurses with plenty of theatre experience. He had already recruited Shirley Gardam and over the coming weeks would recruit six more, for a total strength of eight.

On 25 January 1941 Mina and Shirley sailed to Melbourne with other members of the 2/4th CCS. On 31 January they were joined there by four South Australian AANS recruits, Sisters Irene Drummond and Mavis Hannah, and Staff Nurses Elaine Balfour Ogilvy and Millie Dorsch, who had all entrained from Adelaide the previous day. Irene Drummond had been appointed sister in charge of the unit.

‘ELBOW FORCE’

On 1 February the six nurses entrained for Sydney, presumably with the rest of the unit. Two days later they travelled to Darling Harbour and were taken by ferry to Bradley’s Point, where the famous passenger liner turned troopship Queen Mary was in the process of embarking approximately 5,850 personnel of the 22nd Brigade, 8th Division, 2nd AIF, known as ‘Elbow Force.’

Elbow Force was bound for Malaya, where it would join British and Indian formations in garrisoning the British colonial possession against Japanese expansionism. However, as planning for the expedition had been wrapped in secrecy, the troops had virtually no notion of their destination until shortly before their departure, when they were instructed to hand in all heavyweight uniform and were issued instead with light tropical kit, including drill pants that buttoned up to become shorts.

Travelling with Elbow Force were several medical units, among them the 2/10th AGH, whose staff included 43 AANS nurses, the 2/9th Field Ambulance, elements of the 2/2nd Motor Ambulance Convoy, the 17th Dental Unit – and the 2/4th CCS. Staff of these units, including the nurses, had no greater idea of their destination than the troops had had.

QUEEN MARY

On 3 February at Bradley’s Point, Mina and her 2/4th CCS colleagues boarded the Queen Mary. After finding their cabins, meeting their 2/10th AGH peers, and otherwise getting organised, they proceeded to establish a dressing station on the sixteenth deck, where they would treat the troops’ minor injuries and ailments. More serious cases would be sent to the 2/10th AGH, which had set up an operating theatre and a ward elsewhere on the ship.

The Queen Mary was scheduled to depart the following day with two other troopships, the Aquitania and the Niew Amsterdam. The Aquitania was carrying around 3,300 troops to Bombay, from where they would transship to the Middle East. Travelling on the Aquitania were elements of the 2/7th AGH, including several of the nurses photographed with Mina and Shirley in Hobart. The Niew Amsterdam, which was due to arrive from Wellington, would sail with around 3,800 New Zealand troops. A fourth troopship, the Mauretania, carrying a further 3,900 troops, would join the other three in the Great Australian Bight. Together with their escort craft, the four ships would sail as convoy US 9.

On 4 February, a lovely clear day, all was ready. The troops had completed their embarkation, and countless crates of equipment and supplies had been loaded. In the early afternoon the Queen Mary, the Aquitania and the Niew Amsterdam set off under the escort of HMAS Hobart. Every harbourside vantage point was crowded with cheering people, and small craft crowded round the convoy as the ships pulled away.

Having rendezvoused with the Mauretania, on 10 February the convoy arrived in Fremantle. When it sailed again two days later, Mina and her colleagues had been joined by Staff Nurses Peggy Farmaner from Claremont and Bessie Wilmott from Como. The 2/4th CCS’s nursing complement was now complete. The following day those on board the Queen Mary were officially told that they were bound for Malaya. Some expressed disappointment at the thought of missing all the ‘fun’ of the Middle East. How wrong they would prove to be.

On 16 February, in the vicinity of Sunda Strait, the Queen Mary left the convoy. Those on board the other ships cheered as the mighty ship steamed towards the entrance to the Java Sea under the escort of the British cruiser Durban. Two days later the Queen Mary arrived at Sembawang Naval Base, on the north coast of Singapore Island, just across the Strait of Johor from the Malay Peninsula.

PORT DICKSON

Mina disembarked with her 2/4th CCS colleagues and 2/10th AGH peers. They made their way to adjacent railway sidings, where they gave their names and addresses to Red Cross personnel, were issued with rations, and then entrained for the Malay Peninsula. The 2/10th AGH nurses alighted at Tampin, from where they were driven to the Colonial Service Hospital in Malacca. The 2/4th CCS nurses, apart from Mina, were not yet required by their unit and had been detached to the 2/9th Field Ambulance. They alighted at Seremban, further up the line from Tampin, and were driven to Port Dickson, a town on the west coast of the peninsula, where the 2/9th Field Ambulance would be based. Meanwhile Mina and the other staff of the 2/4th CCS continued to Kuala Lumpur and subsequently moved south to Kajang, where they established a hospital at Kajang High School. After a week at Kajang, Mina joined her AANS colleagues at Port Dickson.

At Port Dickson the 2/4th CCS nurses helped to establish a 50-bed dressing station for the 22nd Brigade troops, whose three battalions, the 2/18th, 2/19th and 2/20th, were based at different camps within the Port Dickson–Seremban area. The dressing station served as a first-aid post, where brigade personnel could receive attention in the event of minor injury or tropical ailment. In more serious cases, they would be transported to the 2/4th CCS at Kajang or the 2/10th AGH at Malacca.

In early July, Elaine Balfour Ogilvy was granted a period leave and travelled to Fraser’s Hill in the highlands north of Kuala Lumpur. As the AANS nurses always travelled in small groups when on leave, it seems likely that Mina and Irene Drummond accompanied her. While there, Elaine played golf with a soldier from the 2/20th Battalion by the name of Bill Gaden, who found the nurses great fun. “We have some super girls at Fraser’s Hill,” he wrote to his mother. “They are Australian nurses and really great sports. They play excellent tennis and golf so we hit things pretty well.”

On 19 July, after five months at Port Dickson, Mina, Elaine and Irene rejoined the 2/4th CCS at Kajang. Millie Dorsch and Shirley Gardam had already rejoined on 7 May and Mavis Hannah on 4 June. Peggy Farmaner and Bessie Wilmott remained at Port Dickson until 20 August, shortly before the redeployment of the 22nd Brigade to the east coast of the peninsula.

SINGAPORE

Mina, Elaine, Mavis and Bessie were granted leave from 11–16 September and travelled to Singapore Island. The famous city on the island was a favoured destination of the AANS nurses. They visited Raffles, sometimes accompanied by officers and sometimes as guests of well-connected locals. They were given privileged access to the exclusive Singapore Swimming Club, with its many facilities. They visited the Singapore Botanic Gardens, with their resident monkeys, and the beautiful Chinese Garden. They were taken out to dinner by officers, followed by dancing or a cabaret, and went on drives. Sometimes they simply went to the cinema. And, of course, the shopping was marvellous.

On 15 September, while Mina and the others were still on leave, another Australian general hospital arrived at Keppel Harbour on Singapore Island aboard the hospital ship Wanganella. The 2/13th AGH had been raised in Melbourne in August at the request of Colonel Alfred P. Derham, Assistant Director of Medical Services, 8th Division, following intelligence reports suggesting the possibility of a Japanese invasion of the island from the north. The unit’s arrival came exactly a month after the arrival of the 27th Brigade, which had been sent to reinforce the 22nd Brigade.

The 2/13th AGH had a staff of some 50 AANS nurses and around 175 officers and other ranks. The unit was billeted at St. Patrick’s School in Katong, on the south coast of Singapore Island, where it would remain while awaiting an order to move into its permanent base, a psychiatric hospital in Tampoi, situated around 8 kilometres from Johor Bahru in the south of the Malay Peninsula. In the meantime, the unit’s nursing staff and orderlies spent time on detachment to the 2/10th AGH and to the 2/4th CCS.

On 19 September Irene Drummond, who had been promoted to the rank of matron on 5 August, was reassigned to the newly arrived 2/13th AGH to take charge of the nursing staff. The following day Matron Drummond was replaced as sister in charge of the 2/4th CCS nurses by Sister Kath Kinsella, from Melbourne, who had arrived on the Wanganella with the 2/13th AGH and had held the rank of temporary matron for the duration of the voyage.

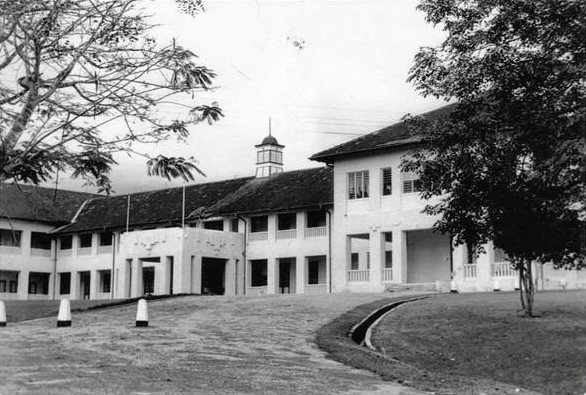

ON THE MOVE

By late September the 2/4th CCS had moved into the same psychiatric hospital in Tampoi earmarked for the 2/13th AGH and had established a small general hospital of 145 beds. The rambling, single-story complex had been leased from the Sultan of Johor and was ringed around by a high iron fence. It also abutted jungle, and as a consequence it was not unusual for scorpions, centipedes and other creatures to invade the wards. In accordance with the terms of the lease agreement, the psychiatric patients were able to remain on site in a separate building.

On 14 October eight nurses arrived at the 2/4th CCS on detachment from the 2/13th AGH. Sister Blanche Hempsted and Staff Nurses Vi McElnea, Eileen Short and Val Smith were from Queensland, Staff Nurses Wilma Oram and Mona Wilton were from Victoria (and best buddies), and Staff Nurses Alma Beard and Iole Harper were from Western Australia.

November was a month of transition for the staff of the 2/4th CCS. By 11 November, 11 more 2/13th AGH nurses had been detached to the unit, making a total of 19. The following day Mina, Peggy, Mavis and Bessie were posted to the camp rest station (CRS) at Segamat, where the 2/29th Battalion of the 27th Brigade was based. Two days later Elaine, Millie, Shirley and Kath Kinsella were posted to the CRS at Batu Pahat to look after the 2/30th Battalion.

Finally the 2/13th AGH received its movement order, and between 21 and 23 November shifted 100 tons of equipment from St. Patrick’s School to Tampoi. At the same time, the 2/4th CCS moved north to Kluang and established a new base next to a civilian hospital on the edge of the aerodrome. The 19 nurses of the 2/13th AGH stayed at Tampoi and were reunited with their unit.

WAR

With Japanese troops now massing in French Indochina, all the signs in the international arena pointed to war. On 1 December the codeword ‘Seaview’ was issued, advancing all Commonwealth forces in Malaya to the second degree of readiness. All leave was cancelled and units had to be ready to move at a few hours’ notice to their war stations. This was followed on the evening of 6 December by the codeword ‘Raffles.’ War with Japan was imminent. All personnel had now to move to their stations, and for Mina, Peggy, Mavis and Bessie in Segamat, that meant proceeding to Kluang at the double. Unfortunately they had to skip a party in the officers’ mess that they were due to attend that night and arrived at mid-morning the next day.

War came a little over 12 hours later. In the very small hours of 8 December, a force of some 5,000 troops of the Imperial Japanese Army launched an amphibious assault at Kota Bharu on the Malay Peninsula’s northern coast. At around the same time, Japanese troops landed at Pattani and Singora (Songkhla) in Thailand. Then at 4.00 am, 17 Japanese bombers attacked Singapore Island. Elsewhere, Pearl Harbour, Guam, Midway, Wake Island and American installations in the Philippines were attacked and Hong Kong was invaded. Japan declared war on the United States, Great Britain, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa. The Pacific War had begun.

On the morning of the invasion, Elaine, Millie, Shirley and Kath arrived at Kluang from Batu Pahat. They found the staff busy making preparations to relocate to the unit’s war station at Mengkibol Estate, a rubber plantation five kilometres to the west of Kluang whose owners were away in India. In anticipation of Japanese hostilities, the site had been earmarked by Colonel Hamilton some days earlier.

That evening Mina and her seven colleagues were transported to Mengkibol with their local amahs (housemaids) and were assigned quarters in a comfortable, two-storey brick bungalow. In the days that followed, they helped to set up a casualty clearing station of more than 80 tents under the cover of long avenues of rubber trees. A central road dubbed ‘Kinsella Avenue’ in honour of Kath divided the surgical section from the medical and resuscitation tents.

Meanwhile, from their beachhead at Kota Bharu, and from two points in Thailand, columns of well-trained, combat-ready Japanese troops, backed by mechanized units and substantial sea and air power, pressed southwards, forcing severely outgunned British and Indian troops to retreat before them. The illusion that had held for so long – that Malaya was well defended – was shattered.

EVACUATION SOUTH

By 29 December it had become clear that the 2/10th AGH at Malacca would have to be evacuated southwards. Colonel Derham decided to move the hospital to Singapore Island but needed time to organise a suitable site. In the interim, on 6 January 1942, 20 of the unit’s nurses were detached to the 2/4th CCS.

The nurses arrived at Mengkibol the following day under the charge of Matron Dot Paschke. On 13 January Matron Paschke left Mengkibol with the commanding officer of the 2/10th AGH, Colonel Edward White, to inspect the site chosen on Singapore Island for the unit’s occupation – Oldham Hall, a Methodist boarding school on Barker Road. In double time Matron Paschke and Colonel White converted the school into a clean and functional 200-bed hospital, and by 15 January the unit had completed its relocation.

Meanwhile, the 2/4th CCS had received its first Australian battle casualties on the night of 14 January. That day, shortly after 4.00 pm, B Company of the 2/30th Battalion ambushed Japanese troops at Gemencheh Bridge, located 50 kilometres to the west of Segamat. This was the first time that Australian troops had engaged Japanese soldiers, and it resulted in five Australian casualties.

The following day the main force of the 2/30th Battalion, together with elements of the 2/4th Anti-Tank Regiment, made further contact with Japanese forces outside Gemas in a battle that lasted two days. Although the Australians scored a tactical victory, they did little to slow the Japanese advance and sustained many casualties. At about 6.00 pm on 15 January a convoy arrived at the 2/4th CCS with 36 casualties. By 6.00 am the following morning, 165 cases had been admitted and 35 operations carried out. And the casualties kept coming in.

BACK IN SINGAPORE

On 19 January, with no Commonwealth troops now remaining between the 2/4th CCS and Japanese positions, Colonel Hamilton was ordered to send the unit’s nurses to the 2/10th AGH on Singapore Island and to move the unit to its fallback position at Fraser Estate rubber plantation, near Kulai in southern Johor. That night Mina, who had now been promoted to the rank of sister, and her seven colleagues set out for Oldham Hall and arrived early the next day.

While the nurses were at Oldham Hall, the 2/4th CCS continued to retreat southwards. After four days at Fraser Estate, on 25 January the unit relocated to the old mental hospital at Johor Bahru (not the site at Tampoi, but another hospital on the waterfront). On 28 January the unit moved again, this time to the Bukit Panjang English School on Singapore Island. Despite its frequent relocation, the 2/4th CCS had treated 1,600 battle casualties since 14 January. Meanwhile, on 25 January the 2/13th AGH had completed its own evacuation, returning to St. Patrick’s School in another stupendous feat of logistics.

Mina and the other nurses rejoined the 2/4th CCS at Bukit Panjang on 30 January. Colonel Hamilton had driven over personally to Oldham Hall to tell them. They were thrilled at the idea of returning to their unit and hastily packed their belongings. When they arrived at Bukit Panjang the orderlies greeted them with cheers, and their presence had a marked effect on the morale of the patients and the other staff.

On the morning of 31 January, after the last Commonwealth troops had crossed onto Singapore Island from the Malay Peninsula, the Causeway linking the two was blown in two places. The breaches brought just eight days’ respite from the unstoppable Japanese, who now controlled the entire peninsula. It had taken just seven weeks.

That same day the nurses were separated again. At the request of Colonel J. G. (Glyn) White, second in command to Colonel Derham, Mina, Millie, Shirley and Mavis were detached to the 2/13th AGH at St. Patrick’s School. That night, their new hospital was bombed. Fortunately there were no fatalities but many of the patients received cuts and bruises. Four days later, on 4 February, Colonel Hamilton sent Bessie, Peggy, Kath and Elaine to Oldham Hall.

THE FINAL DAYS

In the daylight hours of 8 February, Japanese forces began an intensive artillery and aerial bombardment of the western defence sector of Singapore Island. They destroyed military headquarters and communications infrastructure. That night waves of Japanese soldiers landed on the northwestern coast of the island in small boats. They were initially repelled by the Australian 2/20th Battalion and 2/4th Machine Gun Battalion, but the Japanese were too numerous and eventually overwhelmed the Australians, who could not communicate effectively with their command headquarters due to the damage caused that day.

Convoys of Australian casualties, mainly with gunshot and shrapnel wounds, began to pour into the 2/13th AGH, and surgical teams operated around the clock. Soon the hospital became so overcrowded with wounded combatants that outbuildings and even tents were used as wards. Casualties lay closely packed on mattresses on floors or even outside on the lawns, their wounds needing constant attention. Clean linen, drugs and antiseptics were running short, and, worst of all, the municipal water supply had been cut off. Nevertheless, everyone was surprised at how calmly the hospital staff – Mina, Millie, Shirley and Mavis, their 2/13th AGH nursing colleagues, the surgeons, the orderlies – were able to work under such conditions.

At Oldham Hall, meanwhile, Elaine, Peggy, Kath and Bessie and the 2/10th AGH staff were working like Trojans under equally dire conditions.

EVACUATION FROM SINGAPORE

Reports of Japanese atrocities in Hong Kong and elsewhere had been circulating for some time, and already in January, Colonel Derham had asked General H. Gordon Bennett to evacuate the AANS nurses from Singapore. Bennett had refused, citing the damaging effect on morale. Derham then instructed Colonel Glyn White to send as many nurses as he could with Australian casualties leaving Singapore.

Naturally the nurses did not want to leave their patients; it was a betrayal of their nursing ethos, and they protested strongly. Ultimately, they had no choice, and on 10 February six nurses from the 2/10th AGH embarked with several hundred 8th Division casualties on a makeshift hospital ship, the Wusueh, bound for Batavia. Neither Australia nor Britain had sent any commissioned hospital ships. The following day a further 60 AANS nurses, 30 from each of the AGHs, boarded the Empire Star with more than 2,000 evacuees, mainly British army and naval personnel, and set out for Batavia.

On 12 February at 5.00 pm, Mina, Millie, Shirley and Mavis, together with the 27 remaining 2/13th AGH nurses, reluctantly and sadly bid farewell to their patients and were taken in ambulances to St. Andrew’s Cathedral in the city centre. Here they rendezvoused with Elaine, Peggy, Kath and Bessie and the 30 remaining 2/10th AGH nurses. Once assembled, the nurses continued through the devastated city to Keppel Harbour. When the ambulances could go no further, they got out and walked the last few hundred metres. At the wharves there was chaos, as hundreds of people attempted to board any vessel that would take them.

VYNER BROOKE

Eventually a tug took Mina and the other nurses out to a small coastal steamer, the Vyner Brooke. As darkness fell, the ship slid out of Keppel Harbour and after some delay began its journey to Batavia. There were as many as 200 people aboard, mainly women and children, but also a number of men. Behind them, Singapore’s waterfront burned, and thick black smoke billowing high into the night sky.

During the night, the Vyner Brooke’s captain, Richard Borton, guided the vessel slowly and carefully through the many islands that line the passage between Singapore and Batavia. The next day was Friday 13 February. With the ship at anchor in the lee of an island – the better not to be spotted by Japanese planes – Matrons Paschke and Drummond proposed a plan to be put into effect in the event of an attack. The nurses would be placed into teams, each with an area of responsibility on the ship. Each team would maintain discipline and morale within its area, assist the wounded, see to the evacuation of passengers, and then search the ship for stragglers. Only then would the nurses be permitted to leave the ship themselves.

Saturday 14 February dawned bright and clear. After another night of slow progress through the islands, the Vyner Brooke lay hidden at anchor once again. The ship was now nearing the entrance to Bangka Strait, with Sumatra to the starboard side and Bangka Island to port. Suddenly, at around 2.00 pm, the Vyner Brooke’s spotter picked out a plane. It circled the ship and flew off again. Captain Borton, guessing that bombers would soon arrive, sounded the ship’s siren. The nurses donned the lifebelts they had been issued with, and their tin helmets, and took up positions lying on the ship’s deck. The captain then began to zig-zag through open water towards a large landmass on the horizon – Bangka Island. Soon, Japanese dive-bombers appeared, flying in formation and closing fast.

The planes, grouped in two formations of three, flew towards the Vyner Brooke. The ship zig-zagged, and the bombs missed. The planes regrouped, flew in again, and this time scored three direct hits. When the first bomb exploded amidships, the Vyner Brooke lifted and rocked with a vast roar. The next went down the funnel and exploded in the engine room. Then, as the passengers swarmed up to the open air, a third dealt the ship a last, fatal blow. With a dreadful noise of smashing glass and timber, it shuddered and came to a standstill, perhaps 15 kilometres from Bangka Island.

The nurses carried out their action plan. They helped the women and children, the oldest people, the wounded, and their own injured colleagues into the three remaining lifeboats, which were then lowered into the water. One capsized upon entry. Greatcoats and rugs were thrown down to the remaining two, which got away as the ship began to list alarmingly to starboard. After a final search of the ship it was the nurses’ turn to evacuate. They removed their shoes and their tin helmets and entered the water any way they could. Some jumped from the railing on the portside, others practically stepped into the water on the listing starboard side, others slid down ropes or climbed down ladders.

Once in the water, some of the nurses managed to clamber onto the Vyner Brooke’s rafts, which had been thrown overboard by the crew or had slid off the deck as the ship listed. Some grabbed hold of passing flotsam. Others caught hold of the ropes trailing behind the lifeboats. Yet others simply floated in their lifebelts.

BANGKA ISLAND

Mina found herself clinging to the lifeboat that had capsized. It was partially submerged but for now still floating. With her were 2/4th CCS colleague Shirley Gardam, Pearl Mittelheuser of the 2/10th AGH, Jean Ashton, Veronica Clancy, Gladys Hughes and Sylvia Muir of the 2/13th AGH, and a number of civilians. After struggling with the boat for a long time, they abandoned it and joined other passengers around a pair of lashed-together rafts. All night long they swam and pushed. Finally, early on Sunday morning they were picked up by two RAAF men in a motorboat, who deposited them at the end of a long jetty. They had reached the town of Muntok on Bangka Island.

The RAAF men zoomed off again when Japanese soldiers approached. During the night, the Imperial Japanese Army had launched an invasion of Sumatra, and Bangka Island was now under their control. Mina and the others were taken by the soldiers to a large cinema building in the centre of town. Here they were interned with hundreds of surviving passengers of ships sunk by Japanese air and naval forces in Bangka Strait in recent days.

At the cinema Mina, Shirley and the other nurses from their party were reunited with nearly two dozen of their surviving colleagues. Soon, they and the hundreds of other internees were taken to barracks on the edge of town known as the ‘coolie lines’ after the local labourers that lived there in the pay of the Dutch. After they had been there for some 10 days, Vivian Bullwinkel of the 2/13th AGH came into the camp. Through some miracle she had survived a massacre that had claimed the lives of 21 of the nurses and dozens of civilians, merchant seamen and soldiers.

Of the 65 Australian nurses who had set out from Singapore on that fateful day, 12 had perished at sea, including Mina’s 2/4th CCS colleagues Millie Dorsch and Kath Kinsella. Twenty-one had died on a beach near Muntok, Elaine Balfour Ogilvie, Peggy Farmaner and Bessie Wilmott among them. Now Mina, Shirley, Mavis Hannah and the other 29 survivors began a period of three and a half years as prisoners of war.

‘LAVENDER STREET’

On 2 March the internees – nurses, civilians and service personnel – were marched from the barracks down to the jetty at which Mina and Shirley had arrived just two weeks earlier. They waited there overnight and in the morning were taken by barge across Bangka Strait to Sumatra then up the Musi River to Palembang, the women and children in one boat, the men in a larger one that followed. Upon disembarking, the women and children were driven to a MULO (School for More Advanced Primary Education) school on the outskirts of town and found that the men had already arrived.

The next day, some of the interned military men argued with Japanese officials that the AANS nurses should be treated as military prisoners of war, not as civilian internees, but to no avail. That afternoon, the nurses and civilian internees were marched away to the Bukit Besar (‘Big Hill’) district of Palembang, where a number of houses had been sequestered as a makeshift internment camp.

At Bukit Besar Mina and the other nurses were accommodated in two houses abandoned by their Dutch owners. Soon these houses were wanted by the camp’s six Japanese officers for use as a ‘club,’ and the nurses were forced to move to adjacent houses. However, it was soon made clear to the nurses that their presence was required at the ‘opening night’ of the club, the evening of Wednesday 18 March. Wednesday arrived, and some of the nurses were ordered to clean out three houses in a nearby street. Once the purpose of these houses became known, they took to calling them ‘Lavender Street’ after a red-light district in Singapore. Later in the day, five of the nurses were ordered to go into the club in turn, where their willingness to oblige the officers later that evening in ‘Lavender Street’ was gauged. All responded with an unequivocal ‘no.’

At 8.00 pm Wednesday night, 27 of the nurses piled into the club en masse, greatly surprising the Japanese officers. The women had attempted to make themselves appear as ugly as possible – like “gaunt harpies,” according to Elizabeth Simons of the 2/13th AGH – in order to discourage the officers from pursuing their objective, and through determination and resourcefulness they thwarted the officers’ designs. In the days that followed, the officers continued to apply pressure, even threatening to withhold the internees’ food rations, but the nurses were steadfast. Eventually the matter was reported to a local Red Cross official, the club was closed, and the officers from then on ignored the nurses. Nevertheless, the enormous anxiety caused by these events stayed with Mina and the others for a long time.

‘IRENELAAN’

On 1 April the nurses and civilian women and children – including interned Dutch now – were separated from the men and marched off to a new camp in the Talang Semut district of Palembang, a few kilometres east of Bukit Besar. This camp was dubbed ‘Irenelaan’ (Dutch for ‘Irene Avenue’) after the street on which it was partly located. Meanwhile, the men had been taken to their own camp.

Some four hundred women and children were held at Irenelaan. They were crammed into houses on Irenelaan itself and on Bernhardlaan formerly occupied by Dutch residents. The 2/10th AGH nurses were housed at No. 9 Irenelaan and the 2/13th AGH and 2/4th CCS nurses were next door at No. 7. In each of the houses lived a number of civilians as well.

Irenelaan was the least awful camp of the nurses’ long imprisonment. As time passed, they settled into a daily routine, dividing the cooking and housekeeping, and taking turns to be the ‘district nurse.’ Their nurses’ training and army discipline served them well, enabling them to work together to take care of problems. Each house appointed a captain, who spoke on behalf of the others to guards or officials and represented the house at community meetings. Jean Ashton was appointed captain of 2/13th AGH and 2/4th CCS nurses and Pearl Mittelheuser captain of the 2/10th AGH nurse.

To mark Jean Ashton’s birthday, Mina and her pal Val Smith of the 2/13th AGH, a Queenslander, composed an amusing ditty about the awful camp food. It was to be sung to the tune of the well-known war song ‘The Quartermaster’s Store.’ It was debuted on the night of 1 June at a little party held for Jean and continued to be sung at concerts put on by the nurses.

At the start of 1943, Mina was attacked by one of her civilian housemates, Mrs. Close, who occupied an entire room with her four children. Following a protracted dispute over this privileged arrangement, on 14 January she came to blows with Mina, egged on by a certain Miss McMurray. On 7 February Mina and Mrs. Close fought again, in the bathroom. This precipitated the abandonment of No. 7 by the nurses, who moved next door to No. 9.

In March Japanese authorities acknowledged for the first time that they were holding the 32 Australian nurses when their names were broadcast over Tokyo radio. Australian Army authorities conveyed this news to the parents of the nurses but warned them to remain skeptical until the information was confirmed through official channels. Confirmation came later in the year, and in October Laura Raymont received a telegram from Army authorities informing her that her daughter was a prisoner of war.

In the same month that their names were broadcast, the nurses were permitted to send a lettercard to Australia for the first (and only) time. Many of the cards arrived six months later, but is not known whether Laura Raymont ever received Mina’s.

‘ATAP CAMP’

In September 1943 the women and children were moved to a new camp that became known as the ‘Atap Camp’ or the ‘Men’s Camp’ (as it had most recently been occupied by the male internees who were formerly held with the women and children) at Puncak Sekuning, around two kilometres away from Irenelaan.

At the new camp three of the nurses, Betty Jeffrey, Ada Syer (known as Mickey) and Florence Trotter, all of the 2/10th AGH, joined a choir established by a British missionary, Margaret Dryburgh, and a classically trained musician, Norah Chambers. It became known as the Vocal Orchestra. They performed their first concert on the evening of 27 December 1943.

The women of the camp dressed for the occasion, putting on their best clothes. They curled their children’s hair and dressed them as best they could. The concert did wonders for the camp. It helped to renew the women’s sense of human dignity and induced a feeling of being stronger than the enemy. That night, according to Florence Trotter, “everyone forgot about the rats and the filth of the camp.”

In April 1944 the camp came under military administration, where previously it had been under civilian administration. Conditions worsened considerably. Bowing was mandated, and face-slapping and punching occurred regularly. Sadistic punishments such as being made to stand in the sun for hours were meted out. The internees were threatened with starvation unless they dug and tended their own gardens, and even so rations were dangerously inadequate.

By August 1944 the nurses were earning money in various ways to pay for food. Some made hats out of rush bags. Others performed chores, washed clothes or looked after children for the Dutch internees. Val Smith mended shoes. Florence Trotter and Betty Jeffrey cut hair. Mavis Hannah made new garments from old.

Mina, however, could not engage in much physical activity. If she tried to carry water, for instance, she would faint and not recover for days. Consequently the other nurses did not allow her to do much at all, so she sat and sewed to make money. She was able to make pretty little handkerchiefs out of bits and pieces, which were quickly snapped up by those internees with money.

In early September Mina became desperately ill and had to be hospitalised after being punished for allegedly removing a knot of wood from the wall of her hut. She had been sitting on her bedspace quietly sewing, when one of the guards walked in and screamed at her. He accused her of damaging Japanese military property and dragged her outside and made her stand in the sun. Some accounts suggest that her friend Val Smith was made to stand outside too. While the other nurses could tolerate such punishment, Mina certainly could not, and one of the nurses walked over to her and gave her a hat to wear. The same guard rushed over and threw the hat away, before smacking Mina on the face so hard that she was knocked over into the sweet potato patch. She picked herself up and continued to stand for well over an hour. Eventually, however, she began to sway and then passed out, completely unconscious. Her comrades carried her into the hospital, taking not the slightest notice of the guard.

MUNTOK CAMP

A month later the internees were moved in stages back up the Musi River and across Bangka Strait to a camp established at Muntok on Bangka Island. The camp was new and spotless, with big airy buildings that caught the sea breeze. By 10 November Mina’s condition had improved and she was discharged from hospital. Nevertheless, as before, she could do nothing strenuous.

It did not take the nurses long to discover that Muntok camp was, in the words of Elizabeth Simons, in fact “as near hell as we were likely to get” (Simons, p. 84). Malaria and beri-beri became so widespread that little notice was taken of them, and so-called Bangka fever, whose symptoms were fever, high temperatures, rashes and even unconsciousness, began to take hold.

Already weakened by chronic undernourishment, and without the medicines that might have saved their lives, the internees, particularly the eldest and youngest, began to die. They were buried in a small cemetery situated on a hillside in the jungle, not far from the camp. A corner had been set aside for them. The women made coffins and dug the graves with chungkals (a kind of hoe). The Japanese guards provided wooden crosses to mark the graves and inscriptions were burnt into them.

Christmas 1944 was barely celebrated. The nurses made a tired effort to arrange a Christmas concert as in previous years, but simply did not have the energy. There were no presents exchanged among them. They simply had not got a thing.

By late January 1945 all of the nurses except one had contracted malaria. Six were in the camp hospital, four of whom – Shirley Gardam, Blanche Hempstead from Queensland, Rene Singleton from Victoria, and Mina – were gravely ill. The others, despite having malaria themselves, did everything they could for their colleagues. Mina was eventually discharged but on 7 February collapsed and was carried back to hospital. It was thought that she was suffering from cerebral malaria. She was refused medication by Japanese authorities – despite Mavis Hannah’s desperate pleas – and during the night her condition deteriorated.

“NEVER AGAIN WILL THEY HUNGER”

Mina died on 8 February. “Our own Ray, Sister Raymont,” wrote Betty Jeffrey in her book White Coolies (pp. 149–50),

died today after 36 hours of being desperately ill. Ray had an attack of malaria, suddenly became unconscious, and didn’t recover. We are all absolutely rocked. Ray has never really recovered properly since that damned [Japanese guard] made her stand in the sun for so long a few months ago … Val Smith has lost her best friend.

Mina was given a military funeral. The nurses wore their tattered and stained uniforms, and as they carried Mina’s coffin past the guardhouse at the entrance to the camp, the guards stood to attention and removed their caps – something they had never done before. Once outside the camp, the nurses marched down the path to the cemetery and lowered Mina’s coffin into a freshly dug grave.

During the service Val Smith read two passages from the Book of Revelation – chapter 7, verses 9 to 17, and chapter 5, verses 8 to 10, among which were the following lines:

Never again will they hunger; never again will they thirst.

The sun will not beat down on them, nor any scorching heat.

For the Lamb at the centre of the throne will be their shepherd;

He will lead them to springs of living water.

And God will wipe away every tear from their eyes.

The nurses then recited the second and third verses of the hymn ‘Jerusalem the Golden.’

AFTERMATH

Mina was the first of the AANS nurses to die, but she would not be the last. On 20 February Rene Singleton succumbed to malnutrition and disease, followed by Blanche Hempsted on 19 March. Shirley Gardam died on 4 April. Of the eight 2/4th CCS nurses, only Mavis Hannah now remained alive.

In April the internees were taken back across Bangka Strait and up the Musi River to Palembang. They then spent 36 hours on a train to Lubuklinggau in southern Sumatra, from where they were driven in trucks to the Belalau rubber plantation. Around a dozen internees died during the hellish journey.

At the new camp the nurses continued to die of disease and malnutrition. Gladys Hughes succumbed on 31 May, Winnie May Davis on 19 July and Dot Freeman on 8 August.

Three days after the Japanese Emperor formally announced Japan’s surrender on 15 August, Pearl Mittelheuser died.

The surviving 24 nurses flew out of Sumatra on 16 September to Singapore. On 5 October, after a period of recuperation, they boarded the hospital ship Manunda and sailed home. They arrived in Fremantle on 18 October.

IN MEMORIAM

Mina is memorialised across Australia, in the United Kingdom, and in Indonesia.

She will not be forgotten.

SOURCES

- Angell, B. (2003), A Woman’s War: The Exceptional Life of Wilma Oram Young AM, New Holland Publishers.

- Arthurson, L., ‘The Story of the 13th Australian General Hospital, 8th Division AIF, Malaya,’ as reproduced by Peter Winstanley on the website Prisoners of War of the Japanese 1942–1945.

- Ashton, J. and Craig (née Ashton), J. (ed.) (2003), Jean’s Diary, Adelaide.

- Australian War Memorial, AWM52 11/6/6/4 – [Unit War Diaries, 1939-45 War] 2/4 Casualty Clearing Station Malaya, October 1941–February 1942.

- Bassett, J. (1992), Guns and brooches: Australian Army Nursing from the Boer War to the Gulf War, Oxford University Press.

- Colijn, H. (1996), Song of Survival, Millennium Books.

- Gaden, C. (2012), Pounding along to Singapore: a story of the 2/20 Battalion AIF with the letters and diary of Capt. E. W. (Bill) Gaden of ‘D’ Force, POW 1940–1945, CopyRight Publishing.

- Gill, G. H. (1957), Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 2 – Navy, Vol. I – Royal Australian Navy, 1939–1942, Chap. 12 – Australia Station 1941 (pp. 410–463), Australian War Memorial.

- Hamilton, T. (1957), Soldier Surgeon in Malaya, Angus & Robertson.

- Hobbs, Maj. A. F., 2/4th CCS, Diary, presented by Peter Winstanley on the website Prisoners of War of the Japanese 1942–1945.

- Jeffrey, B. (1954), White Coolies, Angus & Robertson Publishers.

- Wigmore, L. (1957), Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 1 – Army, Vol. IV – The Japanese Thrust, Pt. I – The Road to War, Ch. 4 – To Malaya (pp. 46–61), Australian War Memorial.

- National Library of Australia, Oral History Program, ‘Mavis Hannah interviewed by Amy McGrath,’ interview conducted at Grove Hill House, Dedham, Colchester on 13 July 1981, transcript and audio.

- Shaw, I. W. (2010), On Radji Beach, Pan Macmillan Australia.

- Simons, J. E. (1956), While History Passed, William Heinemann Ltd.

- Syer (née Trotter), F. (1995), ‘More Than Conquerors’, from Fisher, F. G. (ed.), ‘We Too Were There: Stories Recalled by the Nursing Sisters of World War II 1939-45’, Returned Sisters sub-branch, R&SLA (Queensland).

- Walker, A. B. (1962), Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 5 – Medical, Vol. II – Middle East and Far East, Part II, Chap. 23 – Malayan Campaign (pp. 492–522), Australian War Memorial.

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS

- The Advertiser (Adelaide, 30 Jun 1916, p. 2), ‘Family Notices.’

- The Advertiser (Adelaide, 16 Sept 1918, p. 11), ‘Advertising.’

- The Advertiser (Adelaide, 8 Apr 1924, p. 9), ‘Trinity College, London.’

- The Advertiser (Adelaide, 13 Apr 1926, p. 12), ‘Family Notices.’

- The Advertiser (Adelaide, 10 Aug 1932, p. 8) ‘Family Notices.’

- The Advertiser (Adelaide, 28 Oct 1943, p. 5), ‘Private Casualty Advices.’

- The Advertiser (Adelaide, 12 Oct 1945, p. 4), ‘Private Casualty Advices.’

- The Areas’ Express (Booyoolee, SA, 30 Jun 1916, p. 2), ‘No title.’

- Australian Christian Commonwealth (SA, 8 Mar 1940, p. 16), ‘The Late Mrs. M. E. Raymont.’

- Chronicle (Adelaide, 23 Aug 1924, p. 53), ‘A Golden Wedding.’

- Examiner (Launceston, 20 Nov 1945, p. 1), ‘Last Photographs Ever Taken.’

- Examiner (Launceston, 21 Nov 1945, p. 5), ‘Fate of Nurses after Fall of Singapore.’

- The Express and Telegraph (Adelaide, 15 Apr 1889, p. 2), ‘Family Notices.’

- The Express and Telegraph (Adelaide, 8 Nov 1915, p. 1), ‘Family Notices.’

- The Mercury (Hobart, 4 Dec 1940, p. 6), ‘Tasmanian Nurses for A.I.F. Service.’

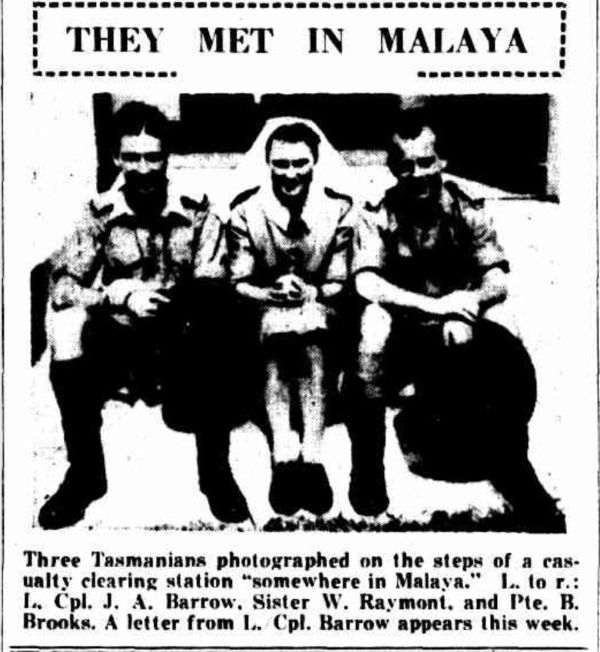

- The Mercury (Hobart, 2 Mar 1942, p. 3), ‘They Met in Malaya.’

- News (Adelaide, 13 Nov 1936, p. 5), ‘Final Exam for Nurses.’

- News (Adelaide, 15 May 1947, p. 7), ‘Memorial Plaque to Slain Nurses.’

- The Register (Adelaide, 30 Jun 1916, p. 4), ‘Family Notices.’

- The Register (Adelaide, 28 Nov 1925, p. 14), ‘Anglican.’

- The West Australian (Perth, 20 Feb 1941, p. 7), ‘The Embarkation.’