AANS │ Staff Nurse │ First World War │ Egypt, France & England

FAMILY BACKGROUND

Mary Florence Stafford was born on 3 April 1891 in Nyngan, central New South Wales. She was the daughter of Lucy Mackereth and Charles James Stafford.

Lucy Mackereth was born in December 1854 on Scott’s Creek in the Adelaide Hills. Her father, George Mackereth, a 28-year-old farmer from Devon, England, arrived in Adelaide aboard the Royal Admiral in January 1838 – only 13 months after the city was founded. Lucy’s mother, Sarah O’Brien, also migrated on the Royal Admiral. Soon after their arrival, Sarah and George were married in the Anglican Trinity Church on North Terrace while it was still being built.

In 1839 George and Sarah acquired land on the banks of Scott’s Creek in the hills to the east of Adelaide and joined a handful of Europeans living in the district. George built a small stone house and planted vegetables and fruit trees. The walls of the cottage still stand today, and some of the trees survived until the early 2000s.

Between 1840 and 1858 Sarah and George had nine children, of whom Lucy was the second youngest. By April 1874 Lucy had moved out of home and become a servant.

Charles Stafford’s background is wrapped in mystery. He appears not to have been born in the colonies. Perhaps he was the Charles James Stafford who was born in Romford, Greater London in March 1843, or the Charles James Stafford born in the Isle of Thanet, Kent in June 1843, or even the one born in Poplar, London in June 1854.

Was he the Charles J. Stafford who in Melbourne in November 1868 pled not guilty to receiving money under false pretences? Or the Charles Stafford who arrived in South Australia in 1876 on the Hesperus, a carriagemaker aged 19?

Mary’s father may have been the Charles Stafford who lived in Boucaut in the northern Clare Valley in South Australia and who was droving on the Broughton River in March 1879. He may have been the Charles Stafford of Orroroo, miner, who in April 1881 travelled to Gawler and stayed at the Commercial Hotel, where he was robbed of a pocketbook containing close to £30. He was quite possibly the Charles James Stafford who travelled to Adelaide from Strathalbyn in May 1884 with a certain Mr. William Jackson and stayed at the Thistle Hotel on Waymouth Street.

Whoever he was, Charles James Stafford married Lucy Mackereth at the Adelaide Registry Office on 2 January 1885. Eight months earlier Lucy had been admitted to Adelaide Hospital with broncho-pneumonia. By then she was a housekeeper living on King William Street in Adelaide.

By 1888 Lucy and Charles had moved to Wilcannia, a boomtown on the Darling River in western New South Wales. At that time Wilcannia was experiencing a period of prosperity based on the transportation of wheat and wool up and down the Darling by paddle-steamer. It was here that Lucy gave birth to her first child, Gertrude.

Within three years the Stafford family had moved 350 kilometres due east to Nyngan in central New South Wales, where, in April 1891, Mary was born. The family appears not to have stayed long in Nyngan, however, for in February 1894 a certain Charles James Stafford was a wine-shop keeper in Narrabri, 300 kilometres northeast of Nyngan – surely our Charles?

Furthermore, on 7 October that same year, Lucy Stafford died in Narrabri West at the age of only 39. Mary and Gertrude had lost their mother, and Charles had lost his wife.

BURRA

We do not know what happened in the aftermath of Lucy Stafford’s tragic death, but by 1898 Mary (and presumably Gertrude) had gone to live with Lucy’s elder sister Mary Mackereth in Burra, a former mining town located around 150 kilometres north of Adelaide.

Mary Mackereth was born in 1842 and was 12 years older than Lucy. She worked at the Redruth Girls’ Reformatory in Burra and before that had been a wardswoman at the Edwardstown Girls’ Reformatory on the southern fringes of Adelaide. In former years she had worked as a charge nurse at Adelaide Hospital and was quite possibly instrumental in helping Mary later to embark upon her own nursing career.

Meanwhile, Charles Stafford disappears from view. (In April 1903, a certain Charles James Stafford was charged with offending against public decency on Oxley Street in Bourke, a Darling River town located halfway between Narrabri and Wilcannia.)

SCHOOL

Mary Stafford (and presumably Gertrude) spent a considerable length of time living in Burra. Mary attended Burra High School, where she was known as Molly. Burra High School was actually a private school opened by Mrs. Frances McLagan in 1891 in ‘Bleak House,’ a former hospital, and continued after her death by her sister, Miss Annie Millar.

Mary was an excellent student. In 1898 she finished top in history and scripture among the junior cohort and was awarded Rev. A. G. King’s scripture prize. Her good work in the junior cohort continued in 1900. In 1903 Mary came first in mapping and tied in reading, writing, drawing and sewing, finishing the year overall third.

On 17 October 1904 Aunt Mary enrolled Mary at Burra State School, where she was exceedingly popular with her fellow students. At the end of the year she was awarded best work among Fourth Class students and the following year finished equal top of Fifth Class with Emily Jones.

On 24 May 1906 the children of Burra State School celebrated Empire Day with appropriate enthusiasm. The day began with Burra’s mayoress, Mrs. Drew, unfurling the Union Jack in front of the school while the children sang ‘The Red, White and Blue’ and saluted the flag. Then the children were addressed on the topics of ‘The significance of the flag,’ ‘Loyalty,’ ‘How Australia is connected with the Empire’ and ‘Heroic deeds in war and explorations.’ After the children sang ‘God Save the King,’ they were taken to Victoria Park for an afternoon of sports, and Mary and her partner came second in the Threading Needle race.

NURSING

In 1911, at the age of 20, Mary was taken on as a probationer nurse at Adelaide Hospital. It seems likely that Aunt Mary helped her to secure this position and may have travelled to Adelaide with her niece. Aunt Mary’s elder sister, Jane Campbell, the eldest of the Mackereth children, lived with her husband at 17 Florence Street in Goodwood, just south of the city centre. Since this was the address that Mary gave when she enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) in 1915, it seems likely that she stayed here when she first arrived in Adelaide. Aunt Mary appears to have stayed here too for a time; in Mary’s military records the address is given alternately as Jane Campbell’s address and Mary Mackereth’s address.

Mary began her nurses’ training in June 1911 and graduated in June 1914 with first-class certificates of efficiency in medical and surgical nursing. For a while during her training she had been in charge of the surgical, gynaecological and infectious ward. After graduating Mary engaged in private nursing and in September 1914 was accepted for registration as a member of the Royal British Nurses’ Association.

ENLISTMENT

By now, the Great War had broken out in Europe, and already many Australian nurses had applied to join the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS). Motivated by a desire to help the Empire and at the same time see something of the world, they were hoping to serve abroad with the AIF.

On 22 January 1915 Mary applied too. Her application was accepted three days later but Acting Principal Matron (South Australia) Alma Hancock noted that Mary was “eligible for AANS only, not active service at present.” Nevertheless, active service was soon to come. On 23 April Mary passed her medical examination and on 26 April signed her agreement to serve abroad with the AIF. Finally on 5 May Mary enlisted in the AIF and was allotted to No. 1 Australian General Hospital (AGH) as a reinforcement staff nurse. As a staff nurse she would be paid at the rate of £60 per annum and 2/6 per diem field allowance, plus free passage from and to Australia and a £15 kit allowance to cover uniform and bedding expenses. Soon Mary and other 1st AGH reinforcements would sail to Egypt on the Royal Mail Ship Mooltan to join their unit in Cairo.

RMS MOOLTAN

On 20 May Mary proceeded to Port Adelaide and boarded the RMS Mooltan with seven other No. 1 AGH reinforcements, five staff nurses and two medical officers. On board they joined the 209 reinforcements – 26 staff nurses, 16 medical officers and 167 privates – who had embarked in Sydney and Melbourne.

The Mooltan was also carrying around 240 personnel of No. 3 AGH, including 74 nurses, with several more due to join in Fremantle. The staff of No. 3 AGH believed that they were bound for France via England, but were in fact destined to end up on the Greek island of Lemnos, where they would work under rudimentary conditions to save the lives of many thousands of Gallipoli casualties.

There was a third contingent of Australian nurses aboard the Mooltan – those who had been appointed to the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service Reserve (QAIMNSR), the British equivalent of the AANS. They were bound for British military hospitals in Alexandria and Cairo.

On the afternoon of 20 May the Mooltan departed Port Adelaide and three days later arrived in Fremantle. Nine more No. 1 AGH personnel embarked, six staff nurses, two medical officers and a private. Of the 38 staff nurses now on board, Mary, at 24 years of age, was the youngest.

The Mooltan left Fremantle on 24 May. The voyage would prove to be interesting but largely uneventful, though the thought of what lay before the nurses charged the whole atmosphere with excitement. After spending a few days in Colombo, the ship made further stops at Bombay and Aden before arriving at Port Tewfik, the port of Suez, on the morning of 15 June. Here Mary and the other 1st AGH reinforcements disembarked. So did the QAIMNSR nurses. The Mooltan continued on its way and arrived at Plymouth, England on 27 June, and soon the staff of the No. 3 AGH were deployed to Lemnos.

HELIOPOLIS, EGYPT

After disembarking, Mary and her colleagues entrained for Cairo and arrived some 12 hours later. They were met by motor ambulances and driven to Heliopolis, on the northeastern outskirts of the city, where No. 1 AGH was based.

The initial contingent of 1st AGH staff had arrived in Egypt aboard HMAT Kyarra on 14 January having departing Fremantle on 14 December 1914. After spending 10 days in Alexandria, the unit moved to Cairo on 24 January and proceeded to set up its hospital in the Heliopolis Palace Hotel – billed, when it opened in 1910, as the most luxurious hotel in Africa. The hospital opened the following day with beds for 200 patients. Meanwhile, the 1st AGH’s sister unit, the 2nd AGH, which had accompanied No. 1 AGH on the Kyarra, established its own hospital at Mena House, which was originally built as a hunting lodge for the Egyptian Khedive Isma’il Pasha and was situated beside the Pyramids of Giza on the southwestern fringe of Cairo.

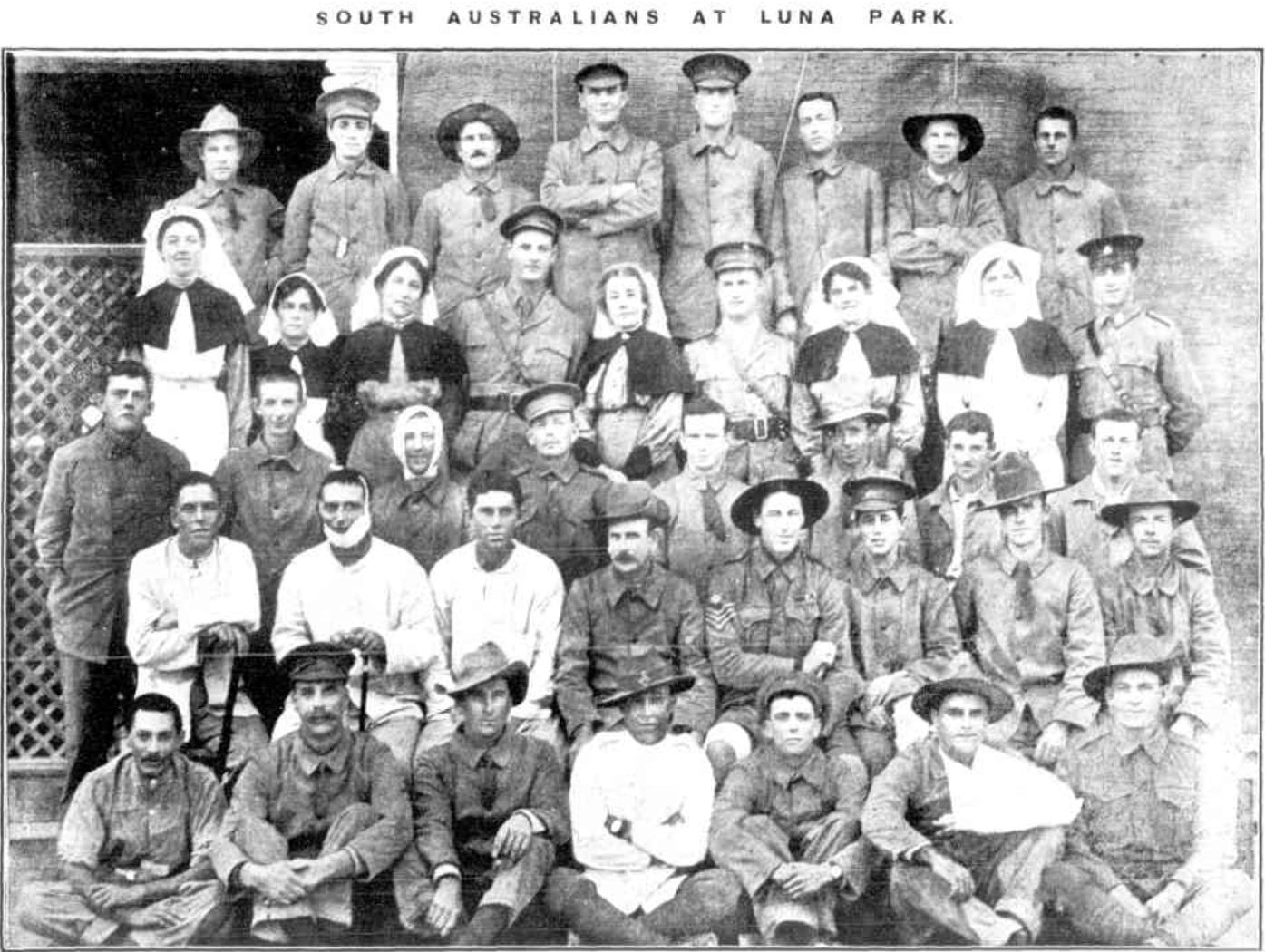

In February No. 1 AGH, already under bed pressure, expanded beyond the Heliopolis Palace Hotel, with the erection of tented wards at the Heliopolis Aerodrome and in front of the hotel. In March the expansion continued, with the acquisition of nearby buildings, including the skating rink of a large pleasure resort known as Luna Park.

When the Gallipoli campaign got underway on 25 April, it quickly became obvious that many more beds would be needed. Additional buildings were taken over, including the upper section of Luna Park, the pavilion, with its amusements such as the Scenic Railway and the Laughter House.

When their ambulances arrived in Heliopolis, Mary and the other nurses were taken to their quarters. They were billetted either at Gordon House, opposite Luna Park, or at the Palace of Prince Ibrahim Khalim, on the outskirts of Heliopolis. Both buildings had recently been acquired to accommodate the influx of reinforcement nurses – not just those from the Mooltan, but also those who had arrived a little earlier on HMAT Kyarra.

The following day Mary and many of her new colleagues were detailed for duty at Luna Park, which by now functioned less like an overflow annex of the Heliopolis Palace Hotel and more like a hospital in its own right. It soon became known as the 1st Auxiliary Hospital. It was reasonably well equipped and could accommodate up to 1,650 patients in beds made of cane, which were cheap and quick to produce but by all accounts very uncomfortable. They were also placed so close together as to make it difficult for the nurses to do their work.

Much of Mary’s work at No. 1 Auxiliary Hospital consisted of dressing bullet and shrapnel wounds. The lower section of Luna Park, the rink, was in effect one large ward, and the patients accommodated here had their dressings applied by nurses who would come to them, even if they could walk. On the other hand, the walking patients of the upper section, the pavilion, would walk from the Skeleton House, Joy Wheel, Laughter House, Scenic Railway, Bandstand etc., each of which had been converted into a small ward, to the Mysterious Cavern, where a dressing room had been set up. This process saved much time.

As the Gallipoli campaign continued, yet more buildings were acquired and converted into general, infectious and convalescent hospitals. By the end of July, the original 520-bed unit that had arrived in Cairo on 24 January had expanded into a 10,000-bed, multicampus hospital.

THE AUGUST OFFENSIVE

In August a new offensive was opened by the Allies that was aimed at capturing the heights of Sari Bair above Anzac Cove. As part of the offensive, between 6 and 10 August Australian troops fought the diversionary Battle of Lone Pine. They captured the position but at the cost of some 2,277 casualties with no strategic gain. On 7 August, in another feint, Australian troops fought the Battle of the Nek, suffering 372 casualties for no gain whatsoever.

The first battle casualties from the renewed fighting reached Heliopolis soon after the offensive began. Their wounds were as shocking as those of the soldiers who had fought at the beginning of the campaign. Many medical cases were arriving as well due to the awful conditions in the trenches.

By 26 August it had become clear that the August offensive had failed. It had cost so many lives and had achieved nothing.

Mary remained attached to No. 1 AGH for the rest of the year and into 1916; whether she stayed at Luna Park or was transferred to another of the auxiliary hospitals, we do not know.

On 1 February 1916 Mary came down with influenza and was admitted to hospital. She was discharged on 4 February and sent on the same day to convalesce at one of the two Red Cross Nurses’ Rest Homes in Alexandria, a journey by train of around four hours. One of the rest homes was a large house situated fairly close to the beach in Ramleh, and the other was a large seaside bungalow about 12 kilometres from Alexandria at Aboukir Bay, the site of Nelson’s victory. Mary stayed in Alexandria until 10 February and then returned to Cairo. She was placed on light duties at the AIF Intermediate Base in Ghezireh, central Cairo, until 16 February, and then returned to Heliopolis.

FRANCE

Following the end of the Gallipoli campaign in early January 1916, the services of the 1st AGH were no longer required in Egypt, and a decision was made to send the unit to northern France. On 29 March Mary and her colleagues entrained for Alexandria and at 5.00 pm the following day departed the Land of the Pharaohs on HMAT Salta, bound for Marseilles. The ship arrived in Marseilles Harbour on the morning of 5 April but the nurses stayed on board. On the evening of 7 April they were informed that their cohort was to be split up among British hospitals in Rouen, Boulogne, Étaples, Le Havre and Le Tréport. They were told that this was a temporary measure and that they would rejoin the 1st AGH at Rouen as soon as accommodation was ready for them.

With some measure of disappointment at this news, Mary and the others finally disembarked on the morning of 8 April, a dismal, wet day, and were granted leave until the evening of the following day. They were taken to the Hotel Regina and then set out to explore the city. They visited several places of interest, including Notre-Dame de la Garde, a Catholic basilica set on a prominence overlooking the old port. They went for gharry drives along the Corniche, enjoying the lovely trees, fountains and sea views, and visited the fish market and flower markets.

At around 2.30 pm on 10 April the nurses, medical staff and orderlies of the 1st AGH, along with the unit’s equipment, entrained for Rouen. Travelling from Provence to Normandy, they passed through Avignon, Macon, Dijon, La Rocher and Nantes, and arrived in Rouen around midday on 12 April. At 2.00 pm the nurses were drafted off in batches and bussed to British hospitals around the town, and after a day or two entrained north for Boulogne, Étaples and Le Tréport or west for Le Havre, where they were posted to their respective hospitals. Fifty of the nurses remained in the Rouen area and rejoined No. 1 AGH on 20 April, which had by then set up a tented hospital on a site at the racecourse vacated by No.12 Stationary Hospital (which had moved north to Saint-Pol-sur-Ternoise). The 1st AGH was ready to receive patients by 29 April, a little over two months before the beginning of the Somme offensive.

Mary was among those (or perhaps the only one) detailed for duty at the Étaples Isolation Hospital and arrived on 14 April. Étaples, situated 150 kilometres north of Rouen, was an important medical evacuation centre, with at least nine British and Canadian general, stationary and convalescent hospitals in operation at the time. Mary remained at the hospital in Étaples for only a short time. However, instead of returning to her unit at Rouen, on 9 May she reported to the Nurses’ Home (in Étaples) for duty aboard No. 24 Ambulance Train.

NO. 24 AMBULANCE TRAIN

Ambulance trains carried casualties from clearing stations close to the front line to base hospitals and onto the Channel ports, from where they would be evacuated to England. Each train could accommodate 400–500 casualties in separate carriages for officers and other ranks. The casualties were classified as ‘lying cases’ and ‘sitting cases,’ depending on the severity of their condition.

The casualties (perhaps only the other ranks) were crammed into narrow, claustrophobic bunks three tiers high with only a few inches of room to spare. Nursing in these conditions was challenging; merely to undress a heavy, badly wounded soldier might require his uniform to be cut away. The train journey was a nightmare for some casualties. With the bunk (or roof) above them so close, they could not, for example, raise their knees to relieve cramp or otherwise shift in their bunks. And for those with broken bones, every jolt of the train hurt.

Mary was accompanied on board by two or three other nurses, three or four medical officers and perhaps two dozen orderlies. One of the nurses would supervise the whole train and be responsible for the officers’ coach, while the other two or three would split the ‘lying’ and ‘sitting’ cases of the other ranks between them.

On Mary’s first day, 9 May, No. 24 Ambulance Train departed Étaples at 8.00 am with four lying and five sitting officers and 80 lying and 64 sitting other ranks on board. It arrived at Calais at 11.15 am and the casualties were offloaded for embarkation for England. On 11 May the train left Calais at 3.35 am and arrived at Lapugnoy at 7.30 am. It was then garaged.

At 5.45 am on 13 May the train departed Lapugnoy and steamed to nearby Chocques, where No. 1 Casualty Clearing Station (CCS) was based. Three lying and seven sitting officers and 78 lying and 71 sitting other ranks were loaded, and the train left at 8.40 am. At 11.30 am it arrived at Bruay-la-Buissière, where two more officers and 77 other ranks were entrained, and left again at 1.45 pm. The following morning at 5.40 am No. 24 Ambulance Train pulled into Rouen and the patients were offloaded.

THE SOMME OFFENSIVE

Such was Mary’s routine for just over three months. Although her work on the train was doubtless difficult at times, it must also have been satisfying, as other nurses have noted, to be doing “real work.”

Nearly two months into Mary’s stint, the Somme offensive began. The human cost of the offensive was staggering. The first day, 1 July, resulted in some 57,000 British casualties, of whom 20,000 were killed. During the first four days, ambulance trains carried more than 33,000 casualties from clearing stations to base hospitals.

On 29 June, two days before the opening of the offensive, No. 24 Ambulance Train left Abbeville at 7.30 am and at 11.15 am arrived at Doullens, 30 kilometres from the front line. Here it was garaged for the rest of the day and for the whole of the next day. Mary and the other staff knew what was coming and must have felt a strange mixture of excitement and dread.

At 4.30 pm on 1 July Mary’s train departed Doullens and at 5.40 pm arrived at Warlincourt-lès-Pas, 20 kilometres away. Here 599 patients from No. 20 CCS were loaded – 14 lying and 21 sitting officers, and 151 lying and 413 sitting other ranks. The train departed at 7.30 pm. After detraining five other ranks casualties at Abbeville, No. 24 Ambulance Train reached Le Tréport at 2.30 am on 2 July and offloaded the casualties for embarkation for England. During these 10 hours Mary and the other staff would likely have worked without a break trying to keep their patients as comfortable as possible. Any reflection upon the human cost of the offensive would have to wait for a quiet moment.

No. 24 Ambulance Train was one of four trains to collect casualties from No. 20 CCS between 3.40 pm on 1 July and 4.00 am the following morning. No. 20 CCS’s war diary shows how an ordinary day became a human tragedy. In the morning, the “weather [was] clear and fine. The camp has dried up thoroughly [following the rain of the previous day]. Very few patients in hospital. About 12 noon a fairly large convoy of wounded was brought in & from this hour the 3 M.A.C. [Motor Ambulance Convoy] brought in wounded in rapid succession. The first ambulance train was filled and left here at 15.40 with 449 patients, the 2nd at 19.30 with 599 [Mary’s train], 3rd at 23.45 with 690 and a 4th at 4 AM with 431.” A total of 2,169 casualties had been cleared by a single CCS in just over 12 hours.

LE TRÉPORT AND ROUEN

On 16 August, having completed her three-month posting on No. 24 Ambulance Train, Mary commenced duty at No. 3 General Hospital (GH) in Le Tréport, a port town lying 80 kilometres south of Étaples. No. 3 GH had partially taken over the Hotel Trianon, a 300-room deluxe hotel completed in 1913 and spectacularly situated atop Les Terrasses, a cliff overlooking the town beach. Like Étaples, Le Tréport was an important hospital centre; another British hospital and two Canadian hospitals were sited on the cliff, and behind Hotel Trianon were row upon row of tents. Large numbers of Somme casualties were still flowing through to these hospitals, six weeks into the offensive.

By December Mary had finally rejoined No. 1 AGH at Rouen. It was now winter, and by all accounts the winter of 1916–17 was one of the harshest on record. The hospital remained predominantly tented, and heating became a problem due to a coal shortage. At one point newly laid water pipes burst, and water became unavailable for a time. Hot water bottles froze, eggs froze, and nurses took their boots to bed to prevent their boots freezing. Frostbite afflicted not only the soldiers in their trenches but the hospital staff too.

Respiratory illnesses broke out among the patients and staff. From 9–15 December Mary suffered an attack of influenza and was sent to a convalescent home in London following a medical board’s recommendation. By 18 January 1917 she was found to be well enough to rejoin her unit and on 16 February returned to Rouen.

ENGLAND

Mary remained with No. 1 AGH at Rouen until 16 July 1917, at which point she was transferred to AIF Headquarters in London. Having made her way to London she was attached to No. 2 Australian Auxiliary Hospital (AAH) in Southall, arriving for duty on 18 July. No. 2 AAH had been established by the AIF in August 1916 in the buildings of the St. Marylebone Schools on South Road in Southall, west London. It had originally functioned as a clearing station for No. 1 AAH, located 15 kilometres away at Harefield Park in northwest London (and not to be confused with No. 1 Auxiliary Hospital, that is, Luna Park), but in November 1916 had begun to specialise in amputations and prosthetics.

On 26 July Mary transferred to the 1st AAH but returned to No. 2 AAH on 9 August pending her embarkation for Australia. She was going home.

RETURN TO AUSTRALIA

Mary had been detailed for duty aboard HMAT Benalla, which was repatriating wounded and medically unfit men to Australia. She embarked on 25 August and the ship departed Plymouth on 30 August. Instead of sailing via the Mediterranean and Red Seas to the Indian Ocean, it sailed via the coasts of West and South Africa.

When the Benalla reached Sierra Leone, one of the soldiers on board, Private Edward Marlay, was taken ashore at Freetown suffering acute appendicitis. He had surgery at Tower Hill Military Hospital but died on 20 September from severe gangrene after a second operation. He was later buried at the Kissy Road Cemetery (today the Freetown King Tom Cemetery).

The Benalla continued on its voyage and reached Cape Town by 27 September and Durban by 3 October. It crossed the Indian Ocean and arrived at Fremantle on the morning of 17 October. After nearly two and a half years away, Mary had returned to Australia. The Benalla anchored overnight and the following day set out for the east coast. Mary disembarked in Melbourne on 24 October and entrained for Adelaide the same day. She was home.

While Mary was away, Gertrude Stafford had married John Ivey (1881–1919) in Claremont in 1916 and had moved to Western Australia. John was originally from Bendigo in Victoria and was a well-regarded miner. Aunt Mary Mackereth had also moved to Western Australia from her sister Jane’s house in Adelaide and was living in Moojebing, near Katanning, 270 kilometres southeast of Perth.

KESWICK AND TORRENS PARK

Mary’s service with the AIF ended on 8 November and the following day she enlisted in the Australian Military Forces (AMF). She was detailed for duty at No. 7 AGH, located at Keswick Army Barracks, immediately southwest of central Adelaide. On 15 January 1918, while still at Keswick, Mary reenlisted in the AIF, but never again had an opportunity to serve abroad.

By mid-1918 Mary had been transferred to No. 15 AGH, based in a mansion on the Torrens Park estate on Adelaide’s southern fringe (and now part of Scotch College). Here she was a great favourite with both patients and staff.

In mid-July it was noted in Mary’s military records that she was “at present on leave from No. 15 AGH awaiting re-embarkation.” Then on 21 October it was noted that she had been “rejected for India … 10 wks ago” (that is, in the first half of August) and that her “pulse [was] rapid & [she was] very easily fatigued.” From this we may conclude that Mary had applied for service in India and had been expecting to go, but had then been told that she could not, due to her health.

Mary’s health continued to deteriorate as the year progressed, and eventually she was diagnosed with lymphatic leukaemia. She died on 19 March 1919 while a patient at No. 15 AGH.

BURIAL

Mary was given a full military funeral, the first time in South Australian history that a nurse had been thus honoured. At 2.30 pm on 21 March the funeral cortege left the hospital and proceeded the short distance to Mitcham Cemetery. The gun carriage was preceded by the firing party and the 4th Military District Band. The mourners included patients from No. 15 AGH and No. 7 AGH at Keswick. Practically every available AANS nurse in the district was in attendance, as well as wardsmaids from the various hospitals. At the conclusion of the service the firing party fired volleys and the bugler played ‘The Last Post.’ Finally the band played ‘Go Bury Thy Sorrow.’ It was a sad and impressive ceremony.

The following day a notice appeared in the Adelaide Advertiser. It read as follows:

“STAFFORD. – In fond and loving remembrance of Sister M. Stafford, who died at Torrens Park on March 20. ‘One of God’s purest.’ Ever remembered by A. M. Tucker.”

In 1923 Mary’s remains were the first to be reinterred in the newly created Garden of Memory at West Terrace Cemetery in central Adelaide. On her headstone are engraved the following words:

In Memory Of

Sister Mary Florence

Stafford

A.N.A.

Died At Torrens Park

19th March 1919

Aged 27 Years

Dearly Beloved Sister of

Gertrude Ivey And Loving

Niece Of Mary Mackereth

“Gone But Not Forgotten”

Erected By Her Sister And Aunt

POSTSCRIPT

Her sister’s death was only the first tragedy to befall Gertrude Ivey in 1919. On 7 November her husband, John Ivey, was killed with two other miners when a section of the Edna May Consolidated Mine, in Westonia, Western Australia, collapsed. He was only 38. At the time of the accident Gertrude was staying with Aunt Mary in Moojebing, having been hospitalised with influenza. She arrived back at Westonia with her aunt by motorcar on 8 November. They were the chief mourners at John’s funeral.

After her husband’s death Gertrude moved to Perth and in the following years undertook a number of enterprises. She kept a lodging house, kept a greengrocer’s and tobacconist’s, and let a holiday property at Trigg Beach. In 1941 she married Graham Vivian of Kenwick and later became a poultry farmer. Gertrude died in Perth in 1971.

In memory of Mary and Gertrude.

SOURCES

- Australian War Memorial, Troopship Movement Cards, 1914–18 War: HMAT Benalla (A24), AWM2018.8.641.

- Australian War Memorial, Australian Imperial Force Unit War Diaries, 1914–18 War, No. 2 Australian Auxiliary Hospital, Southall, August 1916–August 1917, AWM4 26/73/1.

- Australian War Memorial, History of Harefield Park, Harefield (No 1 Australian Auxiliary Hospital) 1914–1919, AWM 449/9/302.

- Australian War Memorial, Nurses’ Narratives, Sister E. A. Cuthbert, AWM41 958.

- Australian War Memorial, Nurses’ Narratives, Sister E. M. Doepke, AWM41 965.

- Australian War Memorial, Nurses’ Narratives, Sister Gertrude M. Doherty, AWM41 966.

- Barrett, J. W. and Percival E. Deane, P. E. (1918), The Australian Army Medical Corps In Egypt, Project Gutenberg.

- Bassett, J. (1992), Guns and Brooches: Australian Army Nursing from the Boer War to the Gulf War, Oxford University Press Australia.

- BirtwhistleWiki (website), ‘2nd Australian Auxiliary Hospital.’

- Burra (website), ‘Burra School Registration – Girls’ and ‘A History of Burra Schools.’

- Butler, J., ‘Very Busy in Bosches Alley’: One Day of the Somme in Sister Kit McNaughton’s Diary,’ Health and History, 2004, Vol. 6, No. 2, Military Medicine (2004), pp. 18–32.

- Goodman, R. (1988), Our War Nurses: The History of the Royal Australian Army Nursing Corps 1902–1988, Boolarong Publications.

- The Long, Long Trail (website), ‘British Base Hospitals in France.’

- The Long, Long Trail (website), ‘Locations of British Casualty Clearing Stations.’

- Lost Hospitals of London (website), ‘No. 2 Australian Auxiliary Hospital, St. Marylebone School, South Road, Southall, Midd’x.’

- National Archives of Australia, Mary Florence Stafford, NAA11615790.

- The National Archives (UK), Army Troops, 20 Casualty Clearing Station (Fourth Army), Jul 1915–Aug 1919, WO 95/499/1-02.

- The National Archives (UK), Army Troops, 43 Casualty Clearing Station (Third Army), Feb 1916–Aug 1919, WO 95/416/3.

- The National Archives (UK), Line of Communication Troops, 24 Ambulance Train, Sept 1915–Apr 1919, WO 95/4137/5.

- The National Archives (UK), Lines of Communication Troops, 24 General Hospital, 1 Jun 1915–31 Dec 1916, WO 95/4085/1.

- The National Archives (UK), ‘Report on the Work of the Australian Army Nursing Service in France,’ from ‘Reports on various Army nursing services in France 1914-1918,’ WO 222/2134, via ScarletFinders (website).

- National Railway Museum, ‘Somme 2016: Ambulance trains of World War 1’ (Alison Kay, archivist).

- State Library of South Australia, ‘Diary of Irene Bonnin, Volumes 1 and 2, 1915–1918,’ PRG 621/21/1-2.

- Toowoomba Grammar School, ‘In Memory of Private Edward William Beverley Marlay.’

- Weekend Notes Adelaide (website), ‘Mackereth Cottage,’ posted 14 May 2012 by Dave Walsh.

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS, MAGAZINES, GAZETTES

- The Advertiser (Adelaide, 19 Sept 1914, p. 13), ‘Royal British Nurses’ Association.’

- The Advertiser (Adelaide, 22 Mar 1919, p. eight), ‘Family Notices.’

- Burra Record (SA, 11 Jan 1899, p. 3), ‘Burra High School.’

- Burra Record (SA, 23 Dec 1903, p. 3), ‘Betsy and Peggy Gossiping.’

- Burra Record (SA, 14 Dec 1904, p. 6), ‘The Burra School.’

- Burra Record (SA, 30 May 1906, p. 4), ‘Empire Day.’

- Burra Record (SA, 26 Mar 1919, p. 3), ‘The Burra Record.’

- The Express and Telegraph (Adelaide, 24 May 1895, p. 2), ‘The Plimpton Reformatory.’

- Kapunda Herald (SA, 5 Jan 1906, p. 6), ‘The Burra School Break-Up.’

- Mail (Adelaide, 22 Mar 1919, p. 3), ‘Personal.’

- Mirror (Perth, 19 Jan 1946, p. 15), ‘Fowl Language to Egg-Man.’

- The Mount Barker Courier and Onkaparinga and Gumeracha Advertiser (SA, Sept 1949, p. 6), ‘Extracts From “History Of Scott’s Creek,” By C. J. Hill Esq.’

- New South Wales Police Gazette and Weekly Record of Crime (Sydney, Feb 1894 [Issue No.9], p. 77), Apprehensions, &c.

- The N.S.W. Red Cross Record (Vol. 1, no. 9, Sept 1915), ‘Red Cross Work In Egypt.’

- Observer (Adelaide, 2 Jun 1923, p. 32), ‘Our Garden of Memory.’

- Observer (Adelaide, 29 Mar 1919, p. 26), ‘Nurse’s Military Funeral.’

- South Australian Register (Adelaide, 21 Jan 1895, p. 5), ‘Old-Time Memories.’

- The Westonian (WA, 7 Nov 1919, p. 2), ‘Serious Mining Disaster.’

- The Westonian (WA, 14 Nov 1919, p. 2), ‘John Ivey and Harry Stockdale.’

- The Westonian (WA, 14 Nov 1919, p. 3), ‘Mine Disaster.’