Staff Nurse │ Second World War │ Egypt, Mandatory Palestine, Greece, Crete, Eritrea│ 2/5th Australian General Hospital

Family Background

Edith Mary Morton, known as Mary, was born on 21 February 1905 at Mount Benger, near Roxburgh, in Otago, New Zealand. She was the daughter of Harriet George (1878–1941), from Roxburgh, whose father was a tin miner from Cornwall, England, and James Michael Morton (1878–1926), from Queenstown, Otago.

Harriet and James were married in 1903 and their first child, Rebecca Edna, was born in the same year. Mary followed in 1905. Sometime between then and 1907 the family moved across the Tasman Sea to Bright in Victoria’s high country, where James worked as an engineer for Harriet’s brother William George, who had moved to Victoria around 1901 and was a manager at the Junction Dredging Co. Two more children were born in Bright, Margery Lilian Douglas in 1907 and Alice Harriet (known as Joan) in 1910.

When William George took over as manager of the Adelong Gold Estates Co. in New South Wales, he took James with him, and the Mortons relocated to Adelong. Here, three more children were born, Lawrence James in 1917, Dorothy in 1919 and Edward Richard in 1922.

NURSING TRAINING

When Mary grew up she decided to become a nurse and was accepted as a trainee at the Royal Alexandra Hospital for Children, in Camperdown, Sydney. In May 1928 she passed her Nurses’ Registration Board examination and on 9 April 1929 was awarded a prize in surgical nursing, specialising in ear, nose and throat surgery, at the hospital’s annual meeting. She gained her registration in general nursing on 12 September that year.

While Mary was training in Sydney, her father died. James Morton had been unwell for some time, and on 19 December 1926, while at the family home in Adelong, he complained of feeling “off colour” and passed away later that day.

ENLISTMENT

In September 1939 Australia entered the Second World War. The Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) reserve was immediately mobilised, and by January 1940 thousands more Australian nurses had applied to join. In the same month, the first AANS contingent under Matron Constance Amy Fall departed Melbourne for Egypt on the Empress of Japan. The nurses were attached to the 2/1st Australian General Hospital (AGH) and were tasked with looking after the troops of the 6th Division, Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF) in Mandatory Palestine.

Mary applied to join the AANS soon after this and was accepted on 27 February 1940. At the time, she was still at the Children’s Hospital in Camperdown, where she appears to have been since completing her training. On 5 June she was one of a contingent of New South Wales nurses whose appointment for overseas duty with the medical units of the 2nd AIF was announced in the newspapers – most of whom, like Mary, would soon join the 2/5th AGH.

The 2/5th AGH had been raised in April 1940 under Colonel William Elphinstone Kay as a 1,200-bed hospital, fully equipped with operating theatres, wards, staff quarters etc. In October 1940 the unit would depart for the Middle East with around 80 AANS nurses, 10 masseuses (physiotherapists), 30 doctors and 200 or so orderlies and other ranks.

In the meantime, on 17 July 1940 Mary went into Victoria Barracks in Paddington and filled out an attestation form for service with the 2nd AIF. She was appointed to the 2/5th AGH and attached to the camp dressing station at the Royal Agricultural Showground in Moore Park, Sydney, where a recruit and reinforcement reception depot was based. Here Mary joined other New South Wales nurses appointed to the 2/5th AGH, including Una Mills, Mollie Nalder and Ruth Tayler. The dressing station comprised a number of wards set up in various pavilions, and here Mary and her new colleagues treated soldiers being recruited to the 7th Division of the 2nd AIF. The nurses were billeted at the Olympia Hotel, opposite the Showground, for the duration of their posting.

EMBARKATION AND DEPARTURE

Soon the day came for Mary to embark for overseas. At around 10.30 am on Saturday 19 October 1940, she and her fellow 2/5th AGH nurses, having said their goodbyes to family and friends, were taken by bus from the Showground to Pyrmont on Sydney Harbour. They boarded a ferry that took them to the passenger liner turned troopship Queen Mary, which was sitting at anchor in Athol Bight near Bradley’s Head. They mounted the gangway and were taken to their cabins on the ‘Deluxe Sun Deck,’ just below the bridge. Later they met other nurses of their unit, and Kathleen Best, their matron.

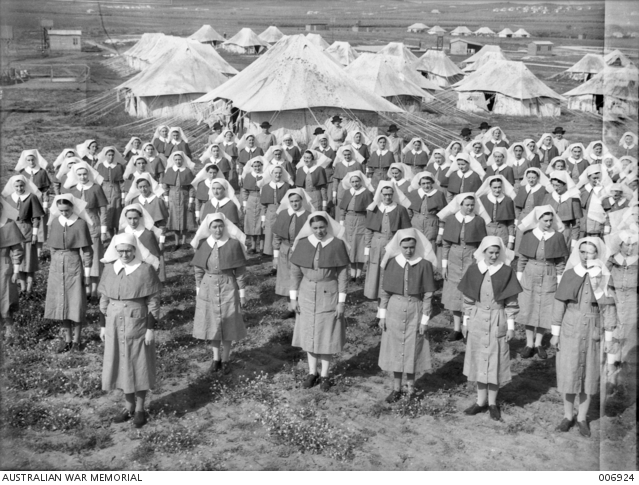

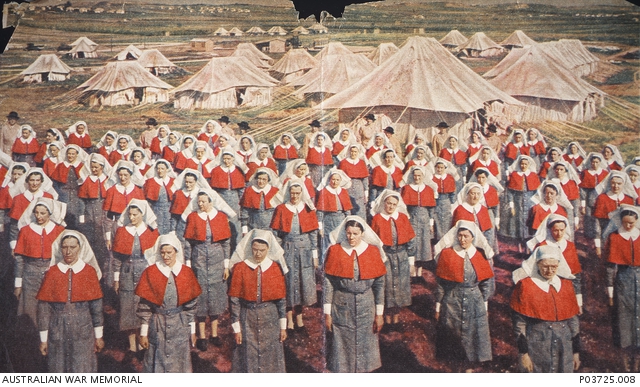

By the following morning, a beautiful, sunny Sunday, around 5,700 troops of the 7th Division had embarked, and the Queen Mary was ready to depart. Everyone assembled on deck – the troops in their khaki, the nurses in their grey uniforms, red capes and white veils – and the 2/13th Battalion band played ‘The Māori Farewell’ (‘Now is the Hour’). Thousands of spectators around the harbour and on scores of small craft cheered and clapped as the mighty ship sailed through the Heads.

The Queen Mary was not the only ship to depart Sydney Harbour that day. It was sailing in company with the Aquitania, which had on board around 2,800 7th Division troops, as well as members of the 2/5th AGH, among them several Queensland nurses. The Mauretania completed the convoy. It had departed Melbourne on 21 October and rendezvoused with the other ships one or two days later. The Mauretania was carrying around 2,300 7th Division troops and elements of various medical units, including eight Tasmanian and four New South Wales nurses of the 2/5th AGH.

INDIA AND EGYPT

After stopping in Fremantle, the convoy arrived in Bombay on 4 November, and here, in the foyer of the Hotel Majestic, Mary and the other nurses of the 2/5th AGH came together for the first time. They spent eight days in Bombay, during which time they went sightseeing and socialised with officers. Some of the nurses were escorted to lunch at a yacht club, while others went to the Taj Mahal Hotel.

On 12 November the journey to the Middle East continued, but now the troops and the staff of the 2/5th AGH and the other medical units were split up among a convoy of smaller ships. The nurses for their part had boarded the Slamat, the Takliwa and the Nevasa among others, and on 25 November, after a brief stop at Port Tewfik, the port of Suez, arrived at El Kantara on the Suez Canal in Egypt.

Sister Lillian Grace Schaefer, Staff Nurse Eileen Grace Beaven, Staff Nurse Enid Sylvia Himmelhoch, Staff Nurse Mina Margaret Back, Staff Nurse Edith Mary Morton

MANDATORY PALESTINE

In El Kantara the nurses ate an unappetising meal and then entrained for Mandatory Palestine. As they stepped up onto the train each was carrying a steel helmet, water bottle, haversack, respirator and kitbag. They disembarked at Gaza, the station for Gaza Ridge, where their sister hospital the 2/1st AGH was based. Initially the 2/5th AGH nurses did not work as a unit, but were instead detached to the 2/1st AGH. The doctors, orderlies and other medical staff of the unit were similarly detached elsewhere.

On 26 December 1940 the 2/5th AGH was established amid orange groves at Kafr Balu near Rehovot, 20 kilometres south of Jaffa, for purposes of administration only. The hospital was not able to start work, as the buildings and other facilities were not ready, and Mary and the other nurses remained detached to the 2/1st AGH. Tragically, one of Mary’s own colleagues, Staff Nurse Jean Gay, died of a ruptured brain aneurism at the 2/1st AGH on 13 February 1941. She had been seriously ill since mid-January.

We do not know how long Mary and the other nurses spent on detachment to the 2/1st AGH, but sometime during the first months of 1941 some of them began to work at their own hospital. They treated battle casualties, of course, but also treated cases of malaria, pneumonia, dengue fever, meningitis and diphtheria.

THE GREEK CAMPAIGN

In late March 1941 those nurses and other staff of the 2/5th AGH who remained on detachment were recalled to their unit at Kafr Balu. In February a decision had been taken to send 6th Division troops to Greece in anticipation of a German offensive. Two hospitals would support the Australians – the 2/6th AGH, to be based at Volos, midway between Athens and northern Greece, and Mary’s unit, to be based at Ekali, just north of Athens. Finally, a year after the 2/5th AGH’s formation, all of its nurses would be working together.

The Greek campaign began on 6 April, when a strong German force invaded northern Greece. It soon overwhelmed the hopelessly undermanned and outgunned 6th Division troops, who were fighting alongside New Zealand and British troops, and forced their evacuation southwards. The nurses of the 2/6th AGH, who had arrived on 3 April and had expected to join the rest of their unit at Volos, were ordered to remain in Athens.

Despite this turn of events, the redeployment of the 2/5th AGH to Greece proceeded, and at 9.00 am on 9 April, 75 AANS nurses and nine physiotherapists under Matron Best, along with the other members of the unit, left Kafr Balu and made their way to Rehovot station from where they entrained after a long wait for El Kantara. They arrived on the eastern side of El Kantara at around 10.30 pm that night. After a supper of sausages and mash they transferred to a train on the western side of the Suez Canal, which took hours, and it was not until 3.15 am on 10 April that the unit was on the move again. After another 10 hours their train terminated at Alexandria’s port.

The 2/5th AGH embarked without delay on the Pennland, and, to the strains of Gracie Fields’s ‘Wish Me Luck as You Wave Me Goodbye,’ Mary and her colleagues set out for Greece. Two days later, on 12 April, the Pennland arrived at Piraeus, the port of Athens. Piraeus had been bombed the previous night, and disembarkation was hazardous. However, at around 7.00 pm Matron Best calmly organised her nurses and their luggage and got them safely into a flotilla of small boats and onto the wharf. The rest of the unit began to follow before disembarkation was suspended due to failing light and the fear of renewed German bombing.

EKALI

The following day disembarkation was resumed and the unit was taken by truck from Piraeus to Ekali, an attractive town set in a wooded valley some 30 kilometres north of Athens, where the unit would be based. As the trucks drove through the Greek capital, people threw flowers at them.

At Ekali tented wards were improvised under the cover of pine trees, as were stores, a pathology laboratory and kitchens. An operating theatre and x-ray facilities were set up in an old adjacent hotel building, with an admission centre and medical records in another. The nurses were billeted in the Hotel Diana, a splendid Art Deco building, while the officers were in cottages vacated by locals and the other ranks were under canvas.

On the evening of 15 April 1941, as facilities were steadily being improved, the hospital received its first patients. More arrived over the following week, including 50 Australians on the night of 17 April, the first casualties of the fighting in the north. Mary’s colleague Mollie Nalder noted their sorry state in her diary. “Such a tired, haggard looking crew,” she wrote. “It made me feel like weeping. Most of them were able to walk and we gave them hot baths – where possible – a hot meal – and got them into bed” (quoted in Bassett, p. 122). A further 150 arrived on the evening of 20 April.

From Ekali the nurses could hear air raid sirens going off in Athens. They heard the sound of anti-aircraft fire and the noise of bombs. They could see German planes flying over, and on one occasion watched them strafe an aerodrome. In the absence of effective opposition they flew so low that the nurses could practically tell the colour of their eyes.

On 19 April the nurses were instructed not to wear their red capes or white veils, as they were considered conspicuous, and it was feared that German pilots would not respect the Red Cross – an order Matron Best thought ridiculous and soon took to ignoring. More sensibly, the nurses were instructed to wear their steel helmets on and off duty.

EVACUATION TO CRETE

On 20 April 1941 Colonel Kay informed Matron Best that her nursing staff and masseuses were to be ready to evacuate at a moment’s notice. Three days later, on 23 April, he came to see the matron again. He wanted her and 39 of her nurses to remain with the hospital, in the full understanding that they would likely be captured, while the other nurses and all of the physiotherapists would be evacuated. Matron Best called for volunteers. The nurses were to write their name and either ‘Stay’ or ‘Go’ on a slip of paper. She promised that only she would ever know what each had written. Every nurse wrote ‘Stay,’ so Matron Best was forced to choose. There is some suggestion that the youngest nurses were chosen to go – among them Jean Bowman, Una Mills, Mollie Nalder and Ruth Tayler, all of whom were in their mid-20s – so it seems likely that Mary, in her mid-30s, was among those to stay.

The departing nurses, in the charge of Sister Janet Cook, Matron Best’s deputy, left at around 5.00 pm on 23 April. Having anticipated entraining for the Greek port of Navplion in the Peloponnese, where they were to be picked up by a waiting ship, they discovered after some hours that the railway line had been bombed. They eventually piled into ten-ton trucks and, jammed in like sardines, joined a convoy to the south. They drove through the night, and on the morning of 24 April stopped for an air raid, taking shelter in a field. Later they sheltered from another air raid in a cemetery, where they remained for the rest of the day. At one point the nurses took the lining out of their helmets and used them to draw water from a well to have a wash. After dark they continued on their way in the trucks, and after alighting walked the last few kilometres to a beach in Navplion. Amid ships burning in the harbour they were ferried out in a fishing boat to HMAS Voyager, and in the early hours of 25 April sailed for Crete.

Late that afternoon the Voyager arrived at Suda Bay in Crete. The nurses disembarked and were taken to the 7th (British) General Hospital (GH) in Canea (Chania), which had been established only a week prior. They set up their mess in the open air and lived on tea, bully beef and biscuits. They washed in the sea and slept in one large tent.

Meanwhile, at Ekali, on 25 April, Matron Best and the nurses, Mary likely among them, were given orders to evacuate within two hours. They packed their haversacks with food for five days, filled their water bottles, and rolled and strapped their blankets. As darkness fell, they boarded trucks and, to the rousing farewells of the remaining men of the unit, were driven to a beach near Megara, 50 kilometres to the west of Ekali. In the early hours of 26 April they were taken out to a merchant ship and sailed for Crete. When German aircraft strafed the ship during the voyage, the nurses donned their steel helmets and found what cover they could, and in lulls helped injured soldiers. They arrived in Crete that afternoon and were reunited with their 2/5th AGH colleagues at the 7th GH.

Left behind in Greece were around 165 staff of the 2/5th AGH under Major Brooke Moore. They had remained to take care of the patients who could not be evacuated, and on 27 April became prisoners of war. Their German captors moved them to Athens, where they continued to run a hospital for some time, before taking them to Germany and Poland. Eventually they were released and returned to Australia, and some ended up serving in the southwest Pacific.

RETURN TO THE MIDDLE EAST

After taking Greece, German forces were in a position to threaten Crete, and late at night on 28 April 1941 the nurses were told to be ready to evacuate early the next morning. When the time came they piled into buses and were driven back to Suda Bay, where they embarked on HMT Ionia, HMT Corinthia and HMAS Voyager for Alexandria.

Mary and her comrades arrived at Alexandria on 1 May and entrained for Cairo. After a week in the Egyptian capital, on 9 May they entrained for Gaza Ridge, where they were split up once again among the 2/1st AGH, the 2/7th AGH – which had taken over the 2/5th AGH’s old site at Kafr Balu – and the 2/11th AGH. Many had lost clothes and other items in the flight from Greece and had to be reequipped.

After several months the 2/5th AGH was reconstituted under Temporary Colonel John Colquhoun Belisario and reinforced with new personnel and new equipment. It was about to be deployed to Eritrea, until recently part of Italy’s East African colonial empire. It was now considered a suitable place to site an AGH due to its remoteness from Egypt should Rommel succeed in capturing that country.

Meanwhile, back in Australia, on 1 August Harriet Morton died suddenly at home in Balgowlah. It must have been a terrible shock for Mary to receive a telegram from Army headquarters informing her of her mother’s death, as presumably she did.

On 24 August the nurses and other members of the unit were instructed to be packed and ready to move by midnight, 26 August. In the event, it was not until 28 August that they entrained for El Kantara and late at night on 29 August continued on to Suez. The nurses were then driven in trucks to the 13th GH, located not far from the Egyptian port town.

Mary and the others stayed at the 13th GH for a number of days and lived under quite difficult conditions. They ate their meals with their British counterparts but were billeted in a camp at some remove from the hospital, with no washing or toilet facilities, and some of the nurses ended up suffering from dysentery. Enclosed by a high barbed wire fence with only one gate, the camp became known as ‘Katie’s Birdcage’ – ‘Katie’ being short for Matron Best’s first name, Kathleen. The nurses’ situation improved when a truck was provided to take them into Suez, where they could swim and have baths at the French Club.

ERITREA

In the end only half of the nurses proceeded to Eritrea, among them Mary. The others returned to Mandatory Palestine. On 6 September 1941 Mary boarded the British troopship President Doumer at Port Tewfik and began a 1,500-kilometre journey south along the Red Sea. After a two-day stop at Port Sudan, the ship arrived on 12 September at Massawa in Eritrea, which had been captured from Italy in May. Massawa had been heavily bombed by the RAF, and the President Doumer had some difficulty avoiding the wrecks that littered the harbour.

The nurses and other staff stayed overnight in Massawa and the following day travelled by road to Gura, a strategically significant town situated 40 kilometres south of Asmara at an altitude of some 2,000 metres. Here the unit established a 600-bed hospital at an aerodrome occupied by the RAF.

It was not long before the 2/5th AGH was ready for the arrival of casualties. However, only one convoy arrived in the three-and-a-half months that the unit was in Eritrea, as it became apparent that the long journey there was exhausting to wounded men. In early November, 20 nurses were sent back to Mandatory Palestine, and soon Army headquarters decided that the entire unit should return.

CAR ACCIDENT

On the night of 15 December, Mary was involved in a terrible car crash. She was thrown from the car and suffered a fracture at the base of her skull and severe abdominal injuries. She died in the early hours of 16 December in the care of her fellow nurses. Decades later, Warrant Officer Lawrence Lane of the 2/5th AGH, spoke of Mary’s death in an interview:

We lost another sister in Eritrea. She went for a ride in an Italian Alfa Romeo that one of the British officers had hooked on and he lost control and hit a mile post – she got killed and he didn’t. The night before we were leaving Eritrea. And everybody knew her as ‘Sunshine.’ Her brother lived in Manly – Tiddy Morton. He used to call her Sunshine.

Mary was buried later that day in the Roman Catholic section of the cemetery at the 32nd BGH at Mai Habar, outside Asmara. Sometime later she was reinterred at the Asmara War Cemetery.

On 17 December a Court of Inquiry held at Gura found that Mary’s death was due to misadventure and that no blame was attributable to any person. Later that day the 2/5th AGH began its relocation, and Mary’s friends and colleagues had to leave behind one of their own.

In memory of Mary.

SOURCES

- 2/5 Australian General Hospital (website), various documents, including ‘Copy of a Report Written by NX23759 Lt. Sylvester Timbs,’ ‘Captain Rosemary (Mollie) Nalder (Edwards) NFX34831’ etc.

- Ancestry.

- Australian Government, Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Anzac Portal, ‘To Stay or Go: Matron Kathleen Best,’ from ‘Devotion: Stories of Australia’s Wartime Nurses.’

- Australian War Memorial, ‘Colonel Kathleen Annie Louise Best.’

- Bassett, J. (1992), Guns and Brooches: Australian Army Nursing from the Boer War to the Gulf War, Oxford University Press.

- Convoyweb (website), Arnold Hague Convoy Database, ‘Pennland.’

- Edwards (née Nalder), R., ‘Greece 1941,’ in Guthrie, S. and Clark, J., eds. (1985), Lighter Shades of Grey and Scarlet.

- Goodman, R. (1988), Our War Nurses: The History of the Royal Australian Army Nursing Corps 1902–1988, Boolarong Publications.

- Henning, P. (2013), Veils and Tin Hats: Tasmanian Nurses in the Second World War.

- National Archives of Australia.

- The National Archives, Registry of Shipping and Seamen: War of 1939–1945; Merchant Shipping Movement Cards, President Doumer, BT 389/24/101.

- University of NSW Canberra, Australians at War Film Archive – Lawrence Lane (Logger) (transcript of interview recorded 29 January 2004).

- University of NSW Canberra, Australians at War Film Archive – Ruth Daly (transcript of interview recorded 10 June 2003).

- University of NSW Canberra, Australians at War Film Archive – Una Keast (transcript of interview recorded 30 May 2003).

- Walker, A. S. (1961), Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 5 – Medical, Volume II – Middle East and Far East, Part I, Chap. 5 – Preparations in the Middle East, 1940 (pp. 86–115), Australian War Memorial.

- Walker, A. S. (1961), Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 5 – Medical, Vol. IV – Medical Services of the Royal Australian Navy and Royal Australian Air Force with a Section on Women in the Army Medical Services, Part III – Women in the Army Medical Services, Chap. 36 – The Australian Army Nursing Service (pp. 428–76), Australian War Memorial.

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic., 1 Nov 1913, p. 2), ‘Porepunkah.’

- Sydney Morning Herald (9 Jun 1928, p. 19), ‘Nurses.’

- Sydney Morning Herald (10 Apr 1929, p. 18), ‘Children’s Hospital.’

- Sydney Morning Herald (5 Jun 1940, p. 15), ‘Nurses for A.I.F.: N.S.W. Contingent.’

- Tumut and Adelong Times (NSW, 21 Dec 1926, p. 1), ‘Death of Mr. James Morton.’

- The Worker (Wagga, NSW, 29 Feb 1912, p. 11), ‘Mines and Miners.’