AANS │ Captain │ Second World War │ 1st Netherlands Military Hospital Ship Oranje & 2/3rd Australian Hospital Ship Centaur

Family Background

Mary Hamilton McFarlane was born on 10 April 1915 in Adelaide, South Australia. She was the daughter of Mabel Mary Hyde (1878–1981) and John Clyde McFarlane (1883–1943), known as Clyde.

Mabel was born in Kilkerran on the Yorke Peninsula, South Australia. She and was the daughter of John and Rachel Hyde of Duck Ponds, Port Lincoln. Clyde was born in Strathalbyn, 50 kilometres southeast of Adelaide. He was the son of John and Sarah McFarlane. As a young man he attended Prince Alfred College in Adelaide then worked briefly at the Coliseum on Rundle Street before going to Port Lincoln in the south of the Eyre Peninsula to work for his uncles, David and Robert McFarlane, who, as McFarlane Bros., ran a general store. In 1907 Clyde took over the management of the McFarlane Bros. branch in Cowell, 160 kilometres northeast of Port Lincoln, and there he met Mabel.

Mabel and Clyde were married on 28 December 1909 at St. Thomas’s Church in Port Lincoln and afterwards lived in Cowell. They had two children, both born in Adelaide – Mary in 1915, and John in 1918.

Early Life

Mary and John grew up in Cowell. When Mary was old enough, she went to Cowell Public School and gained her Qualifying Certificate in November 1926. She then attended Miss Thomas’s Myola School, a private boarding school in Port Lincoln, where she excelled academically and musically. She finished her schooling at Walford House School (now Walford Anglican School for Girls) in Unley, Adelaide, where she was a boarder.

Mary loved music and showed considerable talent. As an 11-year-old, while still in Cowell, she was a noted piano player. At a concert on 25 November 1926, her rendition of Godard’s ‘Fifth Valse’ was generally considered to be the gem of the evening. In 1928, while at Myola School, she finished with the highest aggregate marks in theory and practice of music and gained honours in her Music Board Grade IV examination in Theory of Music.

NURSING

After completing her schooling at Walford in 1934, Mary decided to become a nurse. She began as a probationer at the Cowell District Hospital before completing her training at the Adelaide Hospital, graduating in 1938 equal first in her cohort. Later that year she spent several months in Perth with her uncle, Brig. Percy Muir McFarlane, who had served with distinction in the Second Boer War and First World War and had later become military commandant of South Australia. He had just retired from the same role in Western Australia.

On 29 May 1939 Brig. McFarlane and Mary embarked on the Ormonde for a six-month holiday in England. At one point, her uncle arranged to have Mary presented to King George VI and Queen Elizabeth.

In September the Second World War broke out. Mary had applied to become registered to nurse in the United Kingdom and now offered her services but was unable to obtain an appointment, as hospitals were then fully staffed. Her uncle, meanwhile, offered his services to the British War Office but was informed that he was too old. He did, however, become involved with mobilisation activities and performed voluntary duty as an air raid warden until late October. While her uncle was thus engaged, Mary went to stay with a maternal uncle, Hamley Hyde, in Sussex.

At the end of October Mary and Uncle Percy departed England on their return voyage via the Panama Canal. When their ship was approximately 900 kilometres southeast of Bermuda in the Atlantic Ocean, it began to be followed by a German U-boat. Everyone prepared for the worst. The passengers donned their life jackets, and the lifeboats were swung out, ready to be lowered. After 45 minutes, however, the U-boat gave up the chase, and Mary and her uncle arrived safely in Adelaide on 21 December.

When she arrived home, Mary decided to undertake midwifery training at the Royal Hospital for Women in Paddington, Sydney. On 30 January 1940 she became registered in general nursing in New South Wales and on the evening of 21 February departed Cowell for Sydney. At the end of her training in October she secured the second-highest marks in her cohort and gained her midwifery certificate. She was now double certificated.

ENLISTMENT

Australia was now well and truly in the grip of the Second World War. Mary’s brother, John, had already joined the RAAF, and Mary wanted to play her part. She joined the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) and on 21 January 1941 filled out her attestation form for overseas service with the Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF). On 29 January Mary flew to the Eyre Peninsula to spend a few days with her parents at Cowell before reporting for duty on 4 February at Keswick Military Hospital in Adelaide.

At Keswick Mary signed her oath of enlistment and was posted to the camp hospital at Woodside, 30 kilometres east of Adelaide, as a staff nurse. She commenced duty the same day. On 2 April Mary was transferred to the camp hospital at Wayville in central Adelaide.

Mary was the first nurse from Cowell to volunteer for overseas service, and as a mark of the regard in which she was held, on 24 April, while she was home on leave, she was honoured at a function held at the Franklin Harbour Institute in Cowell. Many of the townsfolk were in attendance, and many kind things were said about her. One of the speakers, Mr W. J. Franklin, mentioned that Mary would probably have occasion to nurse some of the boys with whom she had quarrelled at school. Towards the end of the evening Mary was presented with a petrol iron.

On 29 May, Mary went on leave. She returned to Wayville six days later, now appointed to the rank of sister, and would soon be proceeding overseas. She had been chosen – or would very soon be chosen – for service on a new hospital ship, the Oranje.

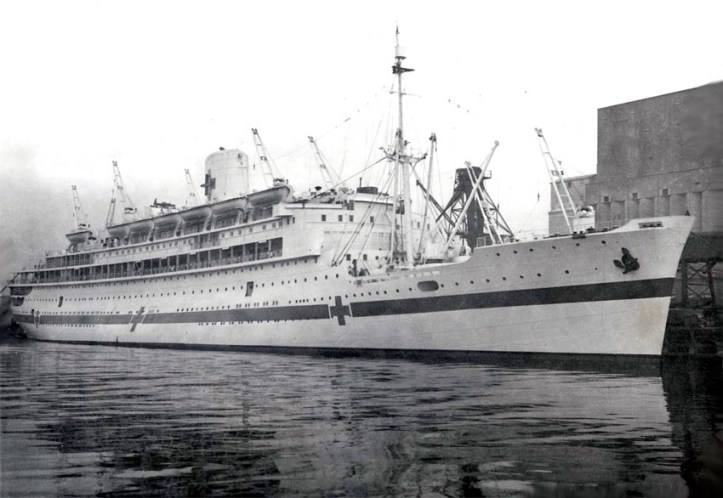

The Oranje

MV Oranje was a newly built Dutch passenger liner designed to sail swiftly between the Netherlands and the Netherlands East Indies (NEI). In December 1939, during its second voyage to the NEI, it was laid up at Surabaya in Java due to the rapidly deteriorating situation in Europe. In February 1941 the NEI government offered the vessel to the Australian and New Zealand governments for use as a hospital ship. On 1 April the Oranje arrived in Sydney and was moored at Cockatoo Island dockyard for conversion. Over the coming weeks, wards, beds, an operating theatre, an x-ray room, a plaster room, a massage room etc. were fitted, and the massive hull was painted white with a green band and red crosses. When complete, the Oranje would be the fastest hospital ship in the world.

On 22 June Mary entrained for Sydney. She arrived two days later and on 25 June was attached to the staff of the Oranje. On 28 June, at an event attended by Prime Minister Menzies, the Oranje was ceremoniously handed over to the Australian and New Zealand governments. It was now officially known as the 1st Netherlands Military Hospital Ship Oranje.

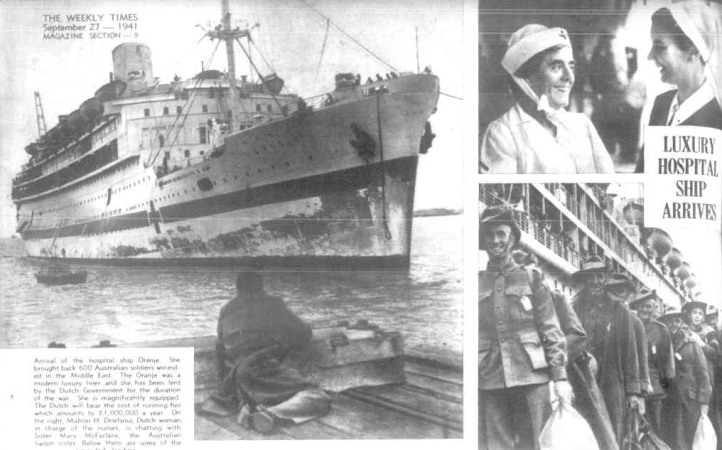

The Oranje would sail under Australian command but fly the Dutch flag. The bulk of its personnel, which included medical officers, 30 nurses under Matron H. Drielsma and 30 Red Cross Voluntary Aid Detachments, were Dutch, although a small number of Australian and New Zealand medical personnel were on board to liaise between the casualties and the Dutch staff.

The First voyages of the Oranje

Mary had been appointed the Australian liaison officer and dietician. On 30 June 1941 she boarded the Oranje and on 3 July the ship departed Sydney for Batavia, where the Dutch medical contingent embarked. After calling into Singapore, the Oranje headed west across the Indian Ocean to Aden, where some delay ensued while the crew awaited German acknowledgement of the vessel’s status as a hospital ship. In the end this did not come, and the captain set off regardless. After narrowly escaping a German bomber in the Red Sea, the Oranje arrived at Port Tewfik, the port of Suez in Egypt, and by 6 August the first of more than 640 Australian and New Zealand troops wounded in the Western Desert campaign were being embarked.

On the return journey the Oranje sailed directly from Suez and arrived in Fremantle on 20 August, having crossed the Indian Ocean in 11 days and 18 hours – record time. After stops in Adelaide and Melbourne, the Oranje arrived in Sydney. Here Mary and other Australian staff members left the ship, and the Australian invalids were disembarked. The Oranje then proceeded across the Tasman Sea to Wellington, where the New Zealanders were disembarked, before returning to Sydney on 4 September.

Mary now enjoyed a period of leave and travelled to Cowell to visit her parents. On 29 September she was attached to the 103rd Australian Convalescent Depot at Ingleburn in southwestern Sydney and remained there until 21 October, just before the second voyage of the Oranje.

On 24 October Mary embarked on her second voyage aboard the Oranje. Sailing once again via South East Asia, the ship arrived in good time at Port Tewfik, embarked nearly 550 sick and wounded troops, and arrived back in Sydney on 11 December.

By then Japan had invaded Malaya and Hong Kong, attacked Singapore, Pearl Harbour, Guam, Midway, Wake Island and the Philippines, and declared war on the United States, Great Britain, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa. The Pacific War had begun.

japan enters the war

On 8 December 1941 the Netherlands declared war on Japan. As a consequence, many of the Oranje’s Dutch medical personnel were ordered to return to the NEI, and Australians and New Zealanders were recruited to take their places. When the Oranje set off on its third voyage on 27 January 1942, Mary had been joined by other AANS nurses – Matron Anne Jewell and Staff Nurses Betty Glasson, Cynthia Haultain, Eva King and Ruth Lindsay. Matron Jewell was in charge of the Australian nurses, and Mary, who had been appointed to the rank of senior sister in December, was her second in charge.

It was now too hazardous to sail via South East Asia, so the Oranje travelled to Aden via Melbourne and Fremantle. In Melbourne three more AANS nurses embarked – Staff Nurses Margaret Adams, Eileen Rutherford and Jenny Walker. From Aden the Oranje continued as usual to Port Tewfik, and 603 Australian and New Zealand patients were embarked. On 9 March the Oranje arrived back in Sydney.

The Oranje departed on its fourth voyage on 24 March. Joining Mary once again were Margaret Adams, Betty Glasson, Cynthia Haultain, Eva King, Ruth Lindsay, Eileen Rutherford, Jenny Walker and Matron Anne Jewell. As the situation in the NEI had worsened, more Dutch staff had been obliged to leave the ship to be replaced by Australians and New Zealanders, and at least two more AANS nurses had joined the staff, Sister Estelle Davis and Staff Nurse Nell Savage.

This time the Oranje sailed across the southern Indian Ocean to Durban, South Africa, and thereafter to Simonstown to go into drydock for a period. During this time Mary and her colleagues were able to take time off for sightseeing. In due course they embarked again and sailed up the East African coast to Port Tewfik, where they took on more than 680 patients. The return journey was uneventful until the very end: soon after the Oranje passed through Sydney Heads on its way to Wellington, it had a close shave with Japanese submarines. The voyage concluded on 3 June with the ship’s return to Sydney.

Mary now had a long break between voyages. On 20 August she was marched out to the hospital at Ingleburn army camp and did not rejoin the Oranje until 27 October.

Between Port Tewfik and Durban

The Oranje’s fifth voyage began on 6 November 1942, as usual from Sydney. Sister Phyllis Vickers and Staff Nurse Elizabeth Smith had now joined Mary, Matron Jewell and the others on the Australian nursing staff, while Staff Nurse Ruth Lindsay had been posted elsewhere.

When the Oranje arrived at Aden on 20 November, having sailed directly from Fremantle once again, the staff were informed that their task this time would be different. Allied troops had recently defeated Rommel’s Afrika Korps in the Second Battle of El Alamein and were now pursuing Rommel westwards, and British, South African, East African and other Commonwealth casualties of the fighting were to be transported from Port Tewfik to Durban, where some would be hospitalised and others transshipped to a British hospital ship.

Embarkation of the patients at Port Tewfik took place on 27 November. Many appeared to have come straight from the battlefield and were in a pitiful state. The 644 casualties were quiet and subdued, quite unlike the rowdy Australian patients of previous voyages. The Oranje reached Durban after a short voyage down the East African coast and the patients were disembarked.

The sixth voyage of the Oranje officially began upon its departure from Durban on 11 December. The ship was returning to Port Tewfik via Aden and arrived on 22 December. To their great delight, staff were given leave in the port, and some of the nurses almost managed to reach Cairo. The following day a further 632 British and Commonwealth casualties were embarked, and at 3.00 pm the Oranje set out once again for Durban.

During the voyage to Durban, Christmas was celebrated, and following a very quiet New Year’s Eve, the Oranje arrived in port on 1 January 1943. Following disembarkation, the nurses were taken to hotels in the city, as the ship was going into dry dock to have its hull scraped. During this period several of the nurses nurses travelled to Oribi Military Hospital in Pietermaritzburg, where many of the British patients from the previous voyage had been taken.

The seventh official voyage began on 6 January, when the Oranje sailed from Durban directly to Port Tewfik, arriving on 16 January. The following day 644 Australian and New Zealand patients were embarked, and that afternoon the Oranje departed for Australia. After two-and-a-half-months, Mary and her colleagues were on their way home. As the Oranje sailed down the Red Sea, it passed that mighty pair, the Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth, on their way to Port Tewfik.

Homeward Bound

As it happened, the Oranje had been instructed to sail to New Zealand first, bypassing Australia. The ship arrived outside Wellington Harbour on 5 February 1943 but was delayed by a thick fog and did not berth until the afternoon. After the New Zealand patients were disembarked, Mary and her colleagues were permitted day leave. They took their walking patients to picnics, dances, lunches and dinners. Some of the nurses, among them Margaret Adams, enjoyed a trip to the snow. After 16 days it was time to leave. As the Oranje slipped out of Wellington Harbour, a band on the wharf played ‘The Māori Farewell’. After stops at Adelaide and Melbourne, the ship arrived in Sydney at 8.00 am on 1 March, and finally on 4 March Mary disembarked.

The Oranje’s return to Sydney marked the end of Australia’s involvement with the ship, as the Australian medical staff were urgently needed at home and in the southwest Pacific to face the Japanese threat. The nurses and other staff were given a fortnight’s leave and told that their unit was to be disbanded. In a letter written to a friend in Hay and printed in the Riverine Grazier on 28 May 1943, Cynthia Haultain expressed her disappointment and that of her colleagues. “We were all very much upset,” she wrote, “as we had been very happy in our job and hated the thought of settling down to life ashore again.” However, they were soon offered another opportunity to serve on a hospital ship. “After ten days at home,” continued Cynthia, “I was recalled to barracks and told that I along with most of the Australian staff of the ‘O’ had been appointed to the Centaur.”

Eight of the Oranje nurses had been attached to the staff of the Centaur: Cynthia, Margaret Adams, Eva King, Eileen Rutherford, Nell Savage, Jenny Walker (all now appointed to the rank of sister), Matron Anne Jewell – and Mary.

The Centaur

The Centaur had been built in Scotland in 1924 and arrived in Australia later that year to ply a route between Fremantle and Singapore. In 1940 the ship was placed under the control of the British Admiralty and at the beginning of 1943 loaned to the Australian government for use as a hospital ship. It was refitted in Melbourne and on 1 March recommissioned as 2/3rd Australian Hospital Ship Centaur.

On 17 March Mary and her seven nursing colleagues boarded the Centaur in Sydney. The ship had arrived from Melbourne on the first leg of a trial run. It had carried only a small number of medical staff, and certain faults and problems that had become apparent during the voyage were now being worked on. The eight Oranje veterans had been joined on board by four more AANS nurses, Sisters Myrle Moston, Alice O’Donnell, Edna Shaw and Joyce Wyllie. Myrle Moston and Joyce Wyllie had previously worked with Nell Savage at the 113th Australian General Hospital in Concord, Sydney.

The second leg of the Centaur‘s trial run began on the morning of 21 March, when the ship sailed out of Sydney Harbour for Brisbane, arriving two days later. More medical staff had joined the ship for this run. On 1 April, after further adjustments had been made, the Centaur departed Brisbane for Townsville, where patients – sick and wounded Australian troops invalided from New Guinea – were embarked for the first time. The ship arrived back in Brisbane on 7 April.

The final leg of the shakedown voyage began on 8 April. That day the Centaur departed Brisbane for Port Moresby and returned on 18 April with Australian and American patients, along with several wounded Japanese prisoners of war. According to Cynthia Haultain, the nurses had missed the “excitement” of the Japanese attack on Port Moresby on 12 April by less than 24 hours.

The nurses were much impressed with the Centaur. Cynthia Haultain noted in her letter that although it was “a tiny little ship, about one-sixth the size of our luxury liner,” it had been “marvellously converted and very well equipped [and carried] nearly half as many patients as the ‘O.’” Mary for her part was somewhat disappointed to find that her cabin did not have an ensuite bathroom but was impressed by the addition of a washbasin with running water and by the fact that a steward made her bed and brought her morning tea. She was surprised at the quality of food on board too. There were salads, fruits, grills, and even lobster mayonnaise.

THE FINAL VOYAGE OF THE CENTAUR

With its capability demonstrated and technical and infrastructural faults corrected, the Centaur was ready to undertake its first voyage proper.

At 10.45 am on 12 May the Centaur departed Sydney bound once again for New Guinea. The ship’s crew had been tasked with transporting 193 members of the 2/12th Field Ambulance to Port Moresby and returning with Australian casualties.

On the evening of the 13 May, while the Centaur was off the northern New South Wales coast, a party was held for Matron Jewell, whose birthday it had been two days earlier. Arthur Waddington, the nurses’ steward, described the party in a story printed in The Australian Women’s Weekly on 29 May 1943. “The matron in charge of the nurses, Matron Ann Jewell … was celebrating her birthday with a party. The nurses had decorated the dining-table with flowers and everything looked very jolly. The party started at dinnertime and there was a lovely birthday cake for her. The nurses bought it in Sydney, and the ship’s cook iced it. It was white icing and had ‘Happy Birthday from the Centaur’ written in pink across it. I noticed that it wasn’t finished at dinner, and they took it to the main saloon to finish it off during the evening. Matron cut a slice for them all. A special menu was served that night, too. I meant to ask her the next day, just for a joke, just how old she really was. I was going to remark that there weren’t any candles on the cake, so was it meant to be a secret. I know she’d have enjoyed the joke.”

At the end of the evening the nurses retired to their cabins.

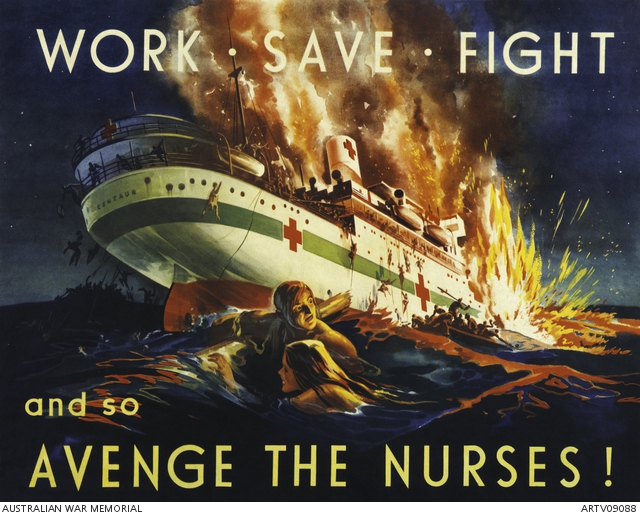

At 4.10 am the next morning, while most of the 332 people on board were asleep, a Japanese torpedo slammed into the Centaur amidships on the port side, just below the nurses’ quarters. The impact caused a fuel tank to explode, and flames tore through the ship. At the same time, it lurched to port, as a massive hole had been torn in the hull.

The bridge collapsed, and the funnel crashed onto the deck. Many of those not killed in the explosion or fire were trapped as the Centaur started to capsize. It was gone in three minutes. There had been no time to launch the lifeboats.

One of the Centaur‘s crew, engineer steward Alex Cochrane of Subiaco, Perth, witnessed Mary’s final moments. On 19 May he told the Melbourne Herald that he “saw Frank Davidson, of Sydney, the ship’s butcher, tie a lifebelt on Sister McFarlane, the night nurse, and help her overboard. But both she and Sister King must have been dragged down by the suction as the ship plunged.”

Mary and 10 of her AANS colleagues died that day. Of the nurses, only Nell Savage survived. Altogether 268 people lost their lives, including 178 members of the 2/12th Field Ambulance. The survivors clambered onto rafts and bits of wreckage and floated on the sea for 34 hours.

IN MEMORIAM

The tragedy of the Centaur was deeply felt by the family and friends of Mary McFarlane. At only 28, her career in nursing was just beginning. According to her school friend Mary Gibson, Mary’s gentle manner and sense of fun made her a favourite among colleagues and patients, and her death came as a great shock to all who knew her.

Mary is remembered at Walford Anglican School, where a bookcase and a chair donated in her honour remain today. An enlarged photograph of Mary in nursing uniform donated by her mother once hung over the bookcase, and the chair was originally used by the Headmistress at assembly. Mary is remembered at Cowell District Hospital, where a plaque and portrait can still be seen.

In memory of Mary.

Sources

- Ancestry.

- COFEPOW (Children and Families of Far East Prisoners of War) (website), ‘The Oranje.’

- Goodman, R. (1992), Hospitals Ships, Boolarong Publications.

- Goossens, R., SS Maritime (website), MS Oranje.

- Howlett, L. (1991), The Oranje Story, Oranje Hospital Ship Association.

- Milligan, C. and Foley, J. (1993), Australian Hospital Ship Centaur: The Myth of Immunity, Nairana Publications.

- National Archives of Australia.

- Sebire, I., ‘Oranje,’ Shipping Today and Yesterday (14 Sept 2021).

- WikiTree, ‘Mary Hamilton McFarlane (1915–1943).’

- Young, N. (2020), ‘Sister Mary Hamilton McFarlane and the Tragedy of the AHS Centaur,’ Virtual War Memorial Australia.

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS

- The Advertiser (Adelaide, 22 Dec 1939, p. 12), ‘Brigadier P. M. McFarlane Returns from London.’

- The Australian Women’s Weekly (29 May 1943, p. 9), ‘Doctor’s Tribute.’

- The Australian Women’s Weekly (29 May 1943, p. 9), ‘Men of Centaur Mourn Loss of Gallant Nurses.’

- Eyre’s Peninsula Tribune (Cowell, SA, 16 Nov 1917, p. 2), ‘Children’s Plain and Fancy Dress Ball’.

- Eyre’s Peninsula Tribune (Cowell, SA, 3 Dec 1926, p. 2), ‘Miss Ivy Willshire’s Students, Concert’.

- Eyre’s Peninsula Tribune (Cowell, SA, 24 Dec 1926, p. 3), ‘Educational Notes.’

- Eyre’s Peninsula Tribune (Cowell, SA, 7 Sept 1939, p. 2), ‘Personal.’

- Eyre’s Peninsula Tribune (Cowell, SA, 22 Feb 1940, p. 2), ‘Personal.’

- Eyre’s Peninsula Tribune (Cowell, SA, 10 Oct 1940, p. 2), ‘Personal.’

- Eyre’s Peninsula Tribune (Cowell, SA, 1 May 1941, p. 2), ‘Social.’

- Eyre’s Peninsula Tribune (Cowell, SA, 4 Sept 1941, p. 2), ‘Personal.’

- Eyre’s Peninsula Tribune (Cowell, SA, 11 Sept 1941, p. 2), ‘Dutch Hospital Ship’s Visit.’

- Eyre’s Peninsula Tribune (Cowell, SA, 20 May 1943, p. 2), ‘Hospital Ship Torpedoed.’

- Eyre’s Peninsula Tribune (Cowell, SA, 22 Jul 1943, p. 2), ‘Death of Mr J. C. McFarlane.’

- Eyre’s Peninsula Tribune (Cowell, SA, 15 Feb 1945, p. 4), ‘J. C. McFarlane Memorial Tablet.’

- The Herald (Melbourne, 19 May 1943, p. 3), ’12 Centaur Survivors in Melbourne.’

- The Mail (Adelaide, 6 Jan 1940, p. 9), ‘In and out of the City.’

- The Mercury (Hobart, 10 Sept 1941, p. 3), ‘Maiden Trip by Oranje as Hospital Ship.’

- News (Adelaide, 11 Jul 1941, p. 3), ‘Trees of Tribute to 11 Old Scholars Of Walford House.’

- News (Adelaide, 10 Sept 1941, p. 8), ‘Dutch Hospital Ship Is Floating Palace.’

- Observer (Adelaide, 21 Dec 1929, p. 30), ‘Walford House School.’

- Port Lincoln Times (SA, 2 Nov 1928, p. 1), ‘Music Examinations.’

- Port Lincoln Times (SA, 21 Dec 1928, p. 3), ‘Religion and Education’.

- Port Lincoln Times (SA, 22 Jul 1943, p. 1), ‘Death of John Clyde McFarlane.’

- The Riverine Grazier (Hay, 28 May 1943, p. 2), ‘Christmas on a Hospital Ship’.

- The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW, 13 Dec 1939, p. 9), ‘New British Army.’

- The West Australian (Perth, 26 May 1939, p. 6), ‘Cocktail Party.’

- West Coast Recorder (Port Lincoln, SA, 20 Dec 1928, p. 14), ‘Prize List Myola 1928.’

- West Coast Recorder (Port Lincoln, SA, 28 Apr 1941, p. 2), ‘35 Years Ago.’

- The West Australian (Perth, 10 Sept 1941, p. 6), ‘Hospital Ship.’