AANS │ Sister Group 2 │ Second World War │ Malaya │ 2/10th Australian General Hospital

Family Background

Mary Dorothea Clarke was born on 20 July 1911 near Rylstone, New South Wales. She was the eldest of six children of Flora Brown (1882–1963) and Percival Henry Clarke (1881–1958).

Flora, a talented artist, grew up on the family property at Mount Brace, seven kilometres east of Rylstone. Percival, a grazier, was born at ‘Fair View’, the family property at Lue, 15 kilometres northwest of Rylstone.

Flora and Percival were married on 1 June 1910 at St. John’s Anglican Church (possibly in Mudgee). After the ceremony, the happy couple left the church to the accompaniment of Mendelssohn’s ‘Wedding March’ and held a reception at the Globe Hotel in Rylstone with 50 guests. That night Flora and Percival took their departure by the mail train for Sydney, where they spent their honeymoon. A large crowd of well-wishers farewelled them at the station.

After their marriage, Flora and Percival lived at ‘Fair View’, which Percival now owned, and here Mary was born in 1911. Her sisters Nellie Blanche Clarke (1913–2013), Rita Ethel Clarke (1914–1999) and Ula Janet Clarke (1917–2005) followed.

In September 1918 Percival sold off portions of ‘Fair View’, including the homestead, and purchased his father-in-law’s Mount Brace property, as Mr. W. L. Brown was moving to Sydney. In November the Clarkes moved in.

More children were born at Mount Brace – Alice Clarke in 1920, and Lee Clarke in 1922.

It is not clear where Mary and her sisters went to school, but they may have attended Rylstone Public School, where their brother, Lee, went in the 1930s.

Nursing and enlistment

In time Mary decided to become a nurse. It was not a surprising decision, given that three of her aunts, Rachel Agnes Clarke, Lilian May Clarke and Lucy Charlotte Clarke, were nurses. In fact, Lilian was matron of Mudgee Hospital. Later Mary’s sister Rita became a nurse too.

Mary began her training at the Coast Hospital (renamed Prince Henry Hospital in 1934) in Little Bay, New South Wales. She passed her final examination in May 1936 and became registered on 13 August. She then trained in midwifery at the Crown Street Women’s Hospital, passing her examination in June 1937 and gaining her registration on 5 August.

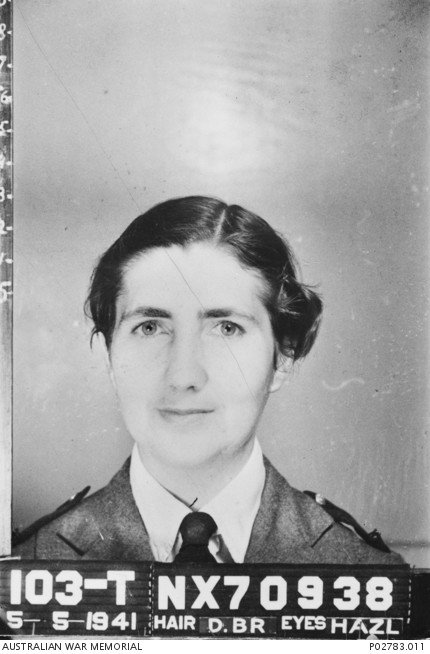

When war broke out, Mary, like so many of her peers, decided to volunteer for service with the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS). She put her name down, had her medical on 18 July 1940, and waited. After finally receiving her call up, she enlisted in 2nd Australian Imperial Force (AIF) on 7 January 1941 and was attached to the Emergency Unit of the AANS at the rank of staff nurse. Mary was then posted to the camp dressing station at Rutherford Camp, near Maitland in the Hunter Valley.

Although she had anticipated serving abroad, Mary was not chosen and her appointment to the 2nd AIF was terminated on 20 February. She immediately transferred to the Australian Military Forces for home service and was posted to the camp dressing station at Tamworth Camp. Two months later Mary had a second opportunity for overseas service. On 25 April she enlisted once again in the 2nd AIF. She did not yet know it, but she had been recruited as a reinforcement for the 2/10th Australian General Hospital (AGH).

HMAT Zealandia

The 2/10th AGH had arrived in Malaya in February on the Queen Mary with nearly 6,000 troops of the 22nd Brigade, 8th Division – the so-called ‘Elbow Force,’ which had been sent to Malaya at Britain’s request to bolster British and Indian troops in garrison duty. The 2/10th AGH had established its hospital in several wings of the Colonial Service Hospital in Malacca. Travelling on the Queen Mary with the 2/10th AGH was the 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station (CCS), with eight AANS nurses attached, and several other medical units.

After her enlistment, Mary returned to Rylstone for a few days’ pre-embarkation leave. While there, she was the guest of honour at a dinner held by the Rylstone sub-branch of the RSL. Her concluding words in response to a toast of the AANS were “I will do my best to keep up the traditions of the profession to which I am honoured to belong.” Just before leaving Rylstone to join her unit, Mary was presented with a leather writing case by the Rylstone Shire Welfare Unit and had already been given a pair of stockings by the local Younger Set.

After bidding her family and friends farewell Mary travelled to Sydney. On 30 April she was posted to the Moore Park Recruiting Depot, where she stayed until 17 May. Two days later she departed Sydney on HMAT Zealandia.

The Zealandia was carrying around 1,200 reinforcements for 8th Division, among whom were fellow 2/10th AGH recruits Sister Jean Stewart from Queensland, Staff Nurse Jenny Greer from New South Wales and masseuse (physiotherapist) Merrilie Higgs from New South Wales. When the ship stopped in Melbourne on 22 May, more 2/10th AGH nurses boarded, including Staff Nurses Nell Keats and Betty Pyman from South Australia and Mary Holden, Betty Jeffrey and Beryl Woodbridge from Victoria. The following day they sailed again, still uncertain of their destination. Several nurses thought they were going to the Middle East.

MALAYA

The Zealandia arrived in Singapore on 9 June towards evening. Mary and the other nurses disembarked and were taken to the railway station dressed entirely inappropriately in their safari jackets, woollen jackets and woollen skirts, shoes, kid gloves, felt hats, shirts, collar and tie. Before the train departed, they were given fruit and a little square of paper on which to write a short note to their families at home advising that they had arrived. After arriving at the railhead town of Tampin at around 3.00 am, the nurses transferred to trucks and were driven to Malacca.

That day, 10 June, the new arrivals were officially attached to the 2/10th AGH, but it was not until the following day that they went on duty. They discarded their collars and ties, wore their linen uniforms, and got to work.

Over the next six months Mary was busy treating the tropical complaints and accidental injuries of the Australian soldiers. She was not overworked, however; there was plenty of time for such off-duty activities as shopping, picnics, dinners and dancing, golf and tennis. As honorary officers, the Australian nurses were permitted to join the exclusive Malacca Swimming Club. They visited tin and gold mines and rubber estates and were taken on long drives through the verdant countryside. They were granted generous periods of leave and visited Singapore, Kuala Lumpur and Fraser’s Hill, a hill station in the highlands north of Kuala Lumpur.

The clouds of war gather

More AANS reinforcements arrived at Malacca early on 18 August. Staff Nurses Jean Russell and Florence Salmon from New South Wales and Beth Cuthbertson, Clarice Halligan and Ada ‘Mickey’ Syer from Victoria had sailed to Singapore on the troopships Johan Van Oldenbarnevelt and Marnix Van St. Aldegonde with 2,000-odd men of the 27th Brigade, deployed to Malaya to bolster 8th Division numbers in the face of mounting international concern over Japanese intentions.

At the urging of Col. Alfred P. Derham, the commanding officer of 8th Division medical services in Malaya, a second AGH was deployed to Malaya and arrived on Singapore Island on 15 September aboard the AHS Wanganella. The 2/13th AGH, staffed by 50 or so AANS nurses and around 175 officers and men, took up billets at St. Patrick’s School in Katong, on the island’s south coast, while it awaited orders to move to its hospital.

Fears of Japanese aggression grew steadily as the year progressed, and by November all the signs in the international arena pointed to war. By the end of November Commonwealth forces in Malaya were advanced to the second degree of readiness, which meant that leave was cancelled, and units had to be ready to move at a few hours’ notice to their areas of deployment. Then, on 4 December, the codeword ‘Raffles’ was given, indicating advancement to the first degree of readiness. War was imminent.

Invasion

Four days later it came. Soon after midnight on 8 December, a force of some 5,000 troops of the Imperial Japanese Army launched an amphibious assault at Kota Bharu on the Malay Peninsula’s northern coast. Four hours later, 17 Japanese bombers attacked Singapore Island.

Not for a minute did the nurses think that the Japanese could possibly reach as far south as Malacca. They were believed to be under-resourced and incapable. In fact, over the next nine weeks Japanese infantry, backed by mechanized units and substantial sea and air power, surged down the Malay Peninsula in three lines of attack at a steady pace of 15 kilometres a day, forcing severely outgunned British and Indian troops to retreat southwards.

By 29 December it had become clear that the 2/10th AGH would have to evacuate from the Colonial Service Hospital. Kuala Lumpur had been bombed, and Malacca was now in the direct path of the Japanese advance. Col. Derham decided to move the hospital to Singapore Island but would need time to organise a suitable site. In the interim, on 29 December Mary and 19 other 2/10th AGH nurses were detached to the 2/13th AGH, which was by now based in a psychiatric hospital in Tampoi, in the southern Malay Peninsula. They arrived the following day.

On 5 January 1942, 16 more nurses and around 40 other staff were detached to the 2/13th AGH. Scores of patients had also been moved south from Malacca to Tampoi. The following day, 6 January, 20 more 2/10th AGH nurses, including Matron Dot Paschke, were detached to the 2/4th CCS, which was at that time based at the Mengkibol Estate, a rubber plantation five kilometres to the west of Kluang.

Oldham Hall

On 13 January, Matron Paschke left Mengkibol with the CO of the 2/10th AGH, Col. Edward Rowden White, to inspect the site chosen on Singapore Island for the unit’s occupation – Oldham Hall, a Methodist boarding school on Barker Road. By 15 January the unit had completed its relocation.

In the meantime, on 14 January Australian 8th Division troops entered combat for the first time. They scored a tactical victory against a Japanese force near the town of Gemas, in northern Johor, but the following day a much bloodier battle was fought. That night convoys of Australian casualties flowed to the 2/4th CCS at Mengkibol and thence to Mary and the other nurses at Tampoi.

Eight days later the 2/13th AGH followed the 2/10th AGH back to Singapore Island. Over the weekend of 24–25 January, the unit returned to St. Patrick’s School, and by the Sunday night Mary had returned to the 2/10th AGH at Oldham Hall.

Since its relocation to Oldham Hall on 15 January, the 2/10th AGH had expanded to occupy Manor House on Chancery Lane, as well as several other buildings in the vicinity. The nurses lived in nearby bungalows that had been abandoned by their British owners.

On 28 January, the 2/4th CCS followed the other two medical units to Singapore Island, relocating to Bukit Panjang English School. Then, on the night of 30 January, the final Commonwealth troops crossed the Causeway from the peninsula to the island. The next morning it was blown up. Soon after, the Imperial Japanese Army reached the northern shore of Johor Strait and on 2 February began a ferocious artillery bombardment of the island. The final battle was about to begin.

The last days of Singapore

On 4 February several shells fell a short distance from Oldham Hall. Three days later, three staff members were killed and several injured. To make matters worse, the large British guns to the south of the hospital were returning fire, so artillery was travelling over the hospital in both directions.

On the night of 8 February Japanese troops began to cross Johor Strait. By the morning, they had established a beachhead on the northwestern corner of Singapore island, despite strong opposition from Australian troops. The heavy fighting produced many casualties, and at Oldham Hall the wards became so overcrowded that men were lying on mattresses on the floor while others waited outside. Operating theatre staff worked around the clock, treating severe head, thoracic and abdominal injuries. There was little respite for staff when off duty either, as the constant pounding of bombs and shells meant that sleep was hard to come by.

With Singapore’s fate all but certain, a decision was made to evacuate the nurses. Already in January, following reports of Japanese atrocities in Hong Kong, Col. Derham had asked General H. Gordon Bennett, commanding officer of the 8th Division in Malaya, to evacuate the AANS nurses. Bennett had refused, citing the damaging effect on morale. Col. Derham then instructed his deputy Lieut. Col. Glyn White to send as many nurses as he could with Australian casualties leaving Singapore.

The nurses’ pleas to be allowed to stay with their patients were ignored, and on 10 February, six of Mary’s 2/10th AGH colleagues embarked with 300 wounded Australian soldiers on the makeshift hospital ship Wusueh. The following day, 11 February, a further 60 AANS nurses, 30 from each AGH, left on the Empire Star. At Oldham Hall, Mary and the remaining nurses said a sad farewell to their departing colleagues, and after seeing them off went back to work. All day long shells whizzed overhead, and bombs dropped around them.

Vyner Brooke

Sixty-five AANS nurses remained in Singapore, but on 12 February they too were ordered to leave. They protested in no uncertain terms. There were so many wounded who needed their help – and besides, they were not at all sure an evacuation ship would even make it out. There was not a plane in the sky and not a ship at sea to protect them.

Nevertheless, they had to go, and late in the afternoon a convoy of ambulances arrived at Oldham Hall. Mary and the others were driven along side streets through Singapore city to St. Andrew’s Cathedral, where they were joined by the remaining nurses of the 2/13th AGH and the 2/4th CCS.

From the cathedral the ambulances proceeded towards Keppel Harbour until they could go no further. The nurses got out and walked the remaining few hundred metres through the devastated city. Fires burned around them, and at the harbour chaotic scenes greeted them, as women and children ran everywhere trying to get on boats. While the nurses waited for their launch, two bombs exploded nearby.

Soon Mary and her 64 comrades were ferried out to a small coastal steamer, the Vyner Brooke, lying at anchor in the harbour. On board already there were as many as 150 people – women, children, and old and infirm men. As darkness fell, the Vyner Brooke slipped out of Keppel Harbour and eventually began its journey south. Behind it, the Singapore waterfront burned, and thick black smoke rose into the sky.

That night the Vyner Brooke made little progress and spent much of Friday hiding among the hundreds of small islands that line the passage between Singapore and Batavia. By the morning of Saturday 14 February, Captain Borton was approaching the entrance to Bangka Strait. To the right lay Sumatra; to the left, Bangka Island.

Suddenly, at around 11.00 am, a Japanese plane swooped over, then flew off again. At around 2.00 pm another plane approached before flying off. The captain, anticipating the imminent arrival of Japanese dive-bombers, sounded the ship’s siren and began a run through open water. When a squadron of dive-bombers appeared on the horizon, Borton commenced evasive manoeuvres.

As the bombers approached, the Vyner Brooke zigzagged wildly at full speed. The first wave of bombs missed. The nine planes banked, lined up again, and came in for a second run. A bomb struck the forward deck, killing a gun crew. Another entered the funnel and exploded in the engine room, causing the ship to lift and rock with a vast roar. A third tore a hole in the side. The Vyner Brooke listed to starboard and began to sink. It was 15 kilometres from Bangka Island.

The nurses carried out the plan that Matron Paschke and Matron Irene Drummond of the 2/13th AGH had devised the previous day. They dispersed to their assigned posts and directed passengers to the Vyner Brooke’s three viable lifeboats. They attended to the wounded, including their own, and helped them to reach the boats. They searched the lower decks for stragglers and then, once Matron Paschke had given the order, abandoned the doomed ship.

Lost at sea

Twelve AANS nurses were lost at sea that day, Mary among them. The other 53 washed ashore on Bangka Island – in lifeboats, rafts, clinging to wreckage or simply drifting in their lifebelts. Twenty-one were killed in a horrific massacre on a beach near the town of Muntok, which only Staff Nurse Vivian Bullwinkel of the 2/13th AGH survived. Vivian joined the remaining 31 in Japanese internment camps on Bangka Island and Sumatra for the next three-and-a-half years. They were finally rescued on 16 September 1945 and a month and two days later came home.

On the morning of 15 June 1944 Mary’s parents received the sad news from Army headquarters that Mary had likely been killed following the sinking of the Vyner Brooke. They had hitherto hoped that she was among those nurses held prisoner on Sumatra, as had initially been reported.

Even with the return of the 24 rescued nurses to Australia, Mary’s parents still did not know what had happened to her.

Letter from Betty Jeffrey

Then, in January 1947, Flora Clarke received a typed, two-page letter from Mary’s 2/10th AGH colleague Betty Jeffrey, and finally learned what had happened to her daughter. The letter read as follows:

Dear Mrs Clarke,

At last I have been able to get hold of your address as I would like to tell you that I was a friend of your daughter Mary – travelled to 10th A.G.H. Malacca with her, and was with her when she was last seen. I would like to tell you what happened.

Sixty-five nursing sisters from Singapore 13th A.G.H., 2/4 C.C.S. and us (10th A.G.H.) left Singapore in the “Vyner Brooke”, a tiny ship not much bigger than a Manly ferry, on Thursday 12th February, 1942. We slept on the floor of the deck and lived there too until Saturday 14th February, when we were found by Japanese bombers, who did their best to sink our ship, and, after a while, succeeded. Some Sisters and many wounded civilians and sisters were able to get away and ashore in two life boats – there were the girls in Sister Bullwinkel’s party – thirty-one sisters swam, and after many hours landed on Banka Island, while some of the girls were drowned owing to rough seas, strong currents and the blackest night on record. Our ship sank at 2.30 pm and just before darkness came, I swam to a raft where I could see grey uniforms. Mary was there – cheery as ever and greeted me as if we had met in the street. You could imagine that. There were many civilian women, two Eurasian children, two wounded (not badly) Malay sailors, Matron Paschke and six of our sisters – far far too many for such a tiny raft.

Before long we soon had it organised as we were quite ten miles from land and had a long way to go. Sister Ennis sat on the raft and held the two children – two slightly wounded but very dazed sisters were also on the raft. Matron, Sister Harper and I took it in turns all that terrible night with the two tiny paddles – just pieces of packing case and very rough. The remaining sisters, women and two sailors were in the water and hung on to the rope at the sides and kicked their feet to help us propel the awkward raft and all its weight through the very strong currents. All through the night we kept changing positions with those in the water to rest them. On many occasions we nearly got to the edge of the breakers but each time we were carried swiftly out to sea again, and it was hopeless. We nearly reached a wharf and later, a lighthouse, but currents would drive us away again. We even ran into part of the Japanese fleet who refused to pick us up as they were about to attack Muntok. At 4 a.m. we saw them take Muntok.

When daylight came, we were many miles out to sea once more and much further down the coast and could not see a sign of anybody or anything but the [Japanese] ships away in the distance. Shore was just visible, not beaches, but trees. Something had to be done. We had wasted all our energy and were further away than at 6 p.m. the night before. As I had burnt my hands very badly getting off the “Vyner Brooke ‘, rowing for twelve hours with a piece of packing case had worn my fingers and palms until the bones were exposed and they were so painful I couldn’t row any more. So I got off the raft. I couldn’t even hold the rope so I just floated alongside the raft. Sister Harper was so tired after her long effort at the other paddle, so she got off too. We also made the heavy Malay sailors leave the raft as they wouldn’t help at all and they also swam with we two sisters. This was much better for those on the raft. It then was able to float on the surface instead of just below the surface. Mary and Sister Ennis took over the paddles and Matron took the children in her arms. Everybody changed over and we set out once more. The sailors, Sister Harper and I slowly swimming a few yards ahead to lead the way while the raft followed. We were very happy about this and our chat was very bright although we were all desperately tired and longing to sleep. We made good progress for a long time, then suddenly the raft was caught in a current that missed us, as they were carried out to sea again and as we had lifebelts on, we could not catch them – only try and keep waving, but they went further away from us each minute. The currents separated we four swimmers; after a few hours we didn’t see the Malays again and, after a long long gruelling swim in the sea and mangrove swamps, Sister Harper and I finally reached shore two days later. We were rescued by native fishermen on the following Tuesday morning. That is the last any one of us saw of Matron Paschke, Mary and the other four sisters and all through those long years as a prisoner I felt sure they would turn up again, perhaps in Singapore, as the raft seemed to be going towards a Japanese destroyer, and the Japanese navy did rescue people who were shipwrecked in Banka Straits as they brought some English Sisters and civilian women into our camp a day or so after we arrived.

Mary, Jean Greer, Beryl Woodbridge, two Sydney Physiotherapists, Merrille and Nan, and I had a grand trip over to Malaya in June, 1941, and we had a wonderful sojourn in Malacca when we were off duty. What a happy family we were! Later on, in Singapore we were all so busy we didn’t seem to see each other until we were taken in ambulances to the wharf to join the “Vyner Brooke”.

Mary was a sweet girl, always so happy and bright and she was still chatting away gaily when I saw her last. I am terribly sorry we could not bring her home to you. Please remember always we did try to get all those girls ashore.

I was discharged from hospital only two months ago, but I have to go back for a few months treatment after I have had a small holiday. I’m so tired of being a patient.

Mrs Clarke, I hope this dreadful story has told you what you must want to know. I have wanted so often to write to Mary’s Mother and tell her, but I only received your address last night from Jean Greer, who is in Melbourne now on her way back to Singapore. Perhaps one day I may see you. My sister-in-law comes from Rylstone and she is anxious for me to stay with her family – Mr and Mrs Thompson at “Wingarra” – when I get away from hospitals finally. How I look forward to that day.

I have very few snaps of our Malacca days. Mine all went down with the ship, but I have two here with Mary in a group – one taken at the Swimming Club showing Sisters Pump, Mary, me, Jennie Greer, ”Woodie” – and the other taken in Singapore standing by a taxi – Merrille, Mary, Nan and “Woodie”. If you haven’t a copy of these, I will get some copies taken off and will send them to you.

I apologise for the length of this letter, but there was so much to tell you. I hope it hasn’t upset you too much.

With kindest regards,

Yours very sincerely

BETTY JEFFREY

Sources

- Cudgegong Valley History Project (website).

- McCullagh, C. (ed.; 2010), ‘Willingly into the Fray: One Hundred Years of Australian Army Nursing’, Big Sky Publishing.

- O’Sullivan, C. (1 Jun 2024), ‘A Mother’s Solace’, Kandos History (website).

- University of NSW, Canberra, Australians at War Film Archive, ‘Elizabeth Bradwell (Betty Pyman) – Transcript of interview, 19 January 2004’.

Sources: Newspapers

- Mudgee Guardian and North-Western Representative (9 June 1910, p. 23), ‘Weddings. Clarke – Brown’.

- Mudgee Guardian and North-Western Representative (19 Sep 1918, p. 24), ‘Local Brevities’.

- Mudgee Guardian and North-Western Representative (10 Aug 1925, p. 1), ‘Local news’.

- Mudgee Guardian and North-Western Representative (24 Apr 1941, p. 6), ‘Personal’.

- Mudgee Guardian and North-Western Representative (23 Apr 1942, p. 17), ‘Prisoner of War’.

- Mudgee Guardian and North-Western Representative (22 Jun 1944, p. 10), ‘Rylstone and Kandos News: Brave Nurse Passes on Sister Mary Clarke Drowned’.

- Mudgee Guardian and North-Western Representative (15 Feb 1945, p. 5), ‘In Memoriam’.

- Mudgee Guardian and North-Western Representative (8 Jan 1948, p. 12), ‘Church Crowded for Memorial Service’.