AANS │ Sister Group 1 │ Second World War │ Malaya │ 2/13th Australian General Hospital & 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station

Family Background

Kathleen Kinsella, known as Kath, was born on 18 March 1904 in South Yarra, an inner suburb of Melbourne. She was the daughter of Mary Susan Lockens (1857–1930) and Michael James Kinsella (1858–1919).

Michael was at different times a labourer, a driver, a van proprietor and later a farmer. In 1877 he married Eliza Jane Findley (1857–1890) at the United Methodist Free Church in Windsor, a suburb adjoining South Yarra. They lived at 25 Grey Street in South Yarra, and later on nearby Wilson Street, and had five children. James George was born in 1878, Eleanor Maud in 1881, and Bertram Michael in 1883. Little Bertram died in 1885 and was followed by another Bertram, born in the same year. Finally, Ethel Martha Eliza was born in 1888.

Eliza Kinsella died in 1890, and in 1892 Michael married Susan Lockens. Five more children were born, all in South Yarra: Daniel Lockens in 1894, Norman Francis in 1895, Arthur Ernest in 1898, Nancy May in 1900, and Kath in 1904.

School and Nursing

In 1905 the Kinsellas moved to ‘Tullamore,’ a property that Michael had bought in 1900 in the locality of Cora Lynn, around 70 kilometres southeast of Melbourne. Here the family ran dairy cattle and grew potatoes, peas and asparagus. Kath attended Five Mile State School in nearby Koo Wee Rup North before transferring in 1912 to Cora Lynn State School with her brother Norman and her sister Nancy. She remained a pupil at Cora Lynn State School until 1918. The following year Michael Kinsella died at the age of 60.

In time, Kath decided to become a nurse and gained a place as a trainee at the Melbourne Hospital. Among her fellow trainees were nurses by the names of Nesta James and Beryl Woodbridge, who would one day join Kath in the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) and serve with her in Malaya. Kath passed her final Nurses’ Board examination in November 1928 – as did Nesta and Beryl – and in February 1929 completed her training. On 28 March 1930 she became a registered nurse, just four weeks after the death of her mother.

Enlistment

Following the outbreak of the Second World War, many Australian nurses volunteered for service. Kath decided to play her part too. On 15 May 1940 she joined the AANS as a staff nurse and on 6 August, while residing – and possibly working – at Heidelberg House, the private wing of the Austin Hospital in Melbourne’s northeastern suburbs, enlisted in the 2nd Australian Imperial Force (AIF). She was now eligible for service abroad with the AANS.

However, Kath’s 2nd AIF enlistment proved ineffective, and on 6 January 1941 she enlisted in the Citizen Military Forces (CMF) for home service. On 30 January she was taken on strength of the 107th Australian General Hospital (AGH) at Puckapunyal army camp in central Victoria and within days was appointed to the rank of temporary sister. On 22 April she was transferred to the 115th AGH, also known as the Heidelberg Military Hospital, which had opened near the Austin Hospital the previous month.

On 5 August, while she was still at Heidelberg, Kath’s appointment to the CMF was terminated and the following day she reenlisted in the 2nd AIF. Her opportunity to serve abroad had now come, and before long she would depart for Malaya as sister in charge of a contingent of nurses attached to a new Australian Army Medical Corps (AAMC) unit. On 7 August Kath was appointed to the rank of temporary matron and on 10 August went on pre-embarkation leave. When she returned from leave on 15 August she was marched in to the new unit, the 2/13th AGH.

2/13th Australian General Hospital

By late 1940, Australian and British authorities had become concerned about Japan’s presence in French Indochina and its relationship with the Vichy government. Coupled with this was intelligence that cast doubt on the capacity of Commonwealth forces in Malaya to counter a major Japanese assault. In December 1940 Australia agreed to deploy troops to Malaya to work alongside their British and Indian counterparts and in February 1941 the 22nd Brigade, 8th Division – known as ‘Elbow Force’ – arrived in Singapore on the Queen Mary. Accompanying the 6,000-odd troops of Elbow Force were a number of AAMC units, principally the 2/10th AGH, the 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station (CCS) and the 2/9th Field Ambulance. Among the AANS nurses serving with the 2/10th AGH were Kath’s Melbourne Hospital colleagues Nesta James and Beryl Woodbridge.

As the year progressed, anxiety over Japan’s intentions in Southeast Asia continued to grow. Moreover, it became clear that Singapore Island, separated from the Malay Peninsula by a causeway over Johor Strait a mere kilometre long, was vulnerable to attack from that direction. It had hitherto been assumed than any aggressive action would come from the south. In response, a second 8th Division brigade, the 27th, comprising the 2/26th, 2/29th and 2/30th Battalions, was sent to Malaya in July to reinforce the 22nd Brigade. It was at this point that Colonel Alfred P. Derham, Assistant Director of Medical Services, 8th Division, Malaya, urged the deployment of additional medical personnel to bolster the AAMC units already there. Australian military authorities agreed, and beginning 11 August the 2/13th AGH was hastily formed at Caulfield Racecourse in Melbourne.

The strength of the 2/13th AGH was set at 225 personnel, including 51 AANS nurses. Kath would be in charge of the nurses for the duration of their voyage to Malaya and upon its conclusion revert to her previous rank. She would then join the 2/4th CCS as senior sister – while Matron Irene Drummond, then in charge of the 2/4th CCS nurses, would become matron of the 2/13th AGH.

However, Kath knew little of this. She knew of course that she had been chosen for service abroad in a leadership role but did not know where. And she cannot possibly have known how perilous the posting would turn out to be.

While Kath was preparing to embark for overseas, her sister Nancy, who had been nursing in England for some years, was serving with the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service Reserve (QAIMNSR) in the Middle East. When the war broke out Nancy joined the QAIMNSR and was sent to France with her unit. On 16 June 1940, following the German invasion of the Low Countries and France, she was evacuated through Saint-Nazaire and was then posted to the Middle East, later returning to France. She was made an Associate of the Royal Red Cross for her exemplary conduct at Nijmegen with the 10th (British) CCS during Operation Market Garden in September 1944.

On 1 September Kath travelled from the 115th AGH in Heidelberg to the Lady Dugan Nurses’ Hostel on Domain Road in South Yarra, where all the Victorian, Tasmanian and South Australian nurses of the 2/13th AGH were assembling. Among the Victorians were Staff Nurses Annie Muldoon, Wilma Oram and Joan Wight, and masseuse (physiotherapist) Cynthia Sutton; among the Tasmanians, Staff Nurses Harley Brewer, Mollie Gunton and Elizabeth Simons; and among the South Australians, Sister Jean Ashton and Staff Nurses Lorna Fairweather and Loris Seebohm. That day they and their new 2/13th AGH colleagues were formally taken on strength.

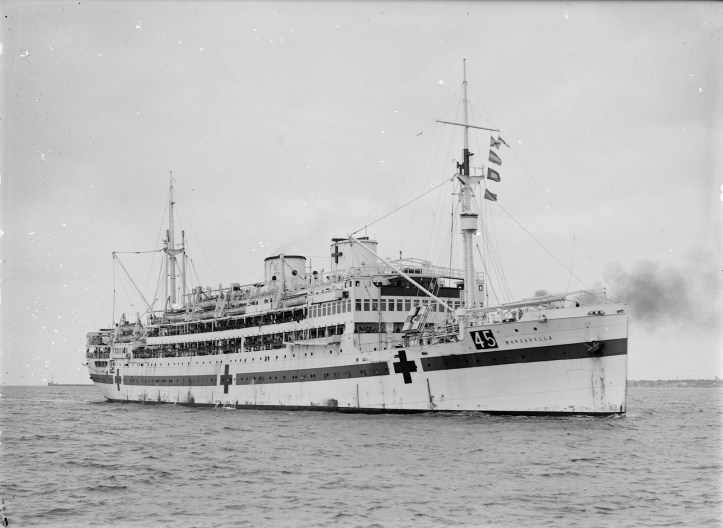

AHS Wanganella

At approximately 9.00 am on 2 September Kath and the other nurses were taken by bus to Port Melbourne. They boarded the Wanganella, which had departed Sydney on 29 August with contingents of 2/13th AGH nurses from Queensland and New South Wales, led respectively by Sisters Julia Powell and Marie Hurley. Formerly a passenger liner plying the route between Australia and New Zealand, the Wanganella had been refitted in May and recommissioned as 2/2nd Australian Hospital Ship Wanganella in July. This was the ship’s first voyage as a hospital ship.

On 8 September the Wanganella arrived in Fremantle after a rough passage across the Bight. Seven AANS nurses boarded – Sisters Eloise Bales and Vima Bates and Staff Nurses Sara Baldwin-Wiseman, Alma Beard, Iole Harper and Gertrude McManus – while one nurse, weak and dehydrated, was disembarked and transshipped back to the eastern states. The following afternoon the ship pulled out of Fremantle’s inner harbour, sailed past the Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth, which were carrying troops bound for the Middle East, and headed in a northerly direction over a very placid Indian Ocean. Shortly afterwards those on board were officially told that they were bound for Malaya.

During the voyage the nurses spent their time demonstrating bandaging and other basic nursing procedures to the unit’s orderlies. They attended lectures on tropical medicine and ran their own sick bay on a roster system. For half an hour each morning they practised using their gas masks and tin helmets. During leisure time they played quoits on deck and enjoyed the other entertainments on board.

Singapore

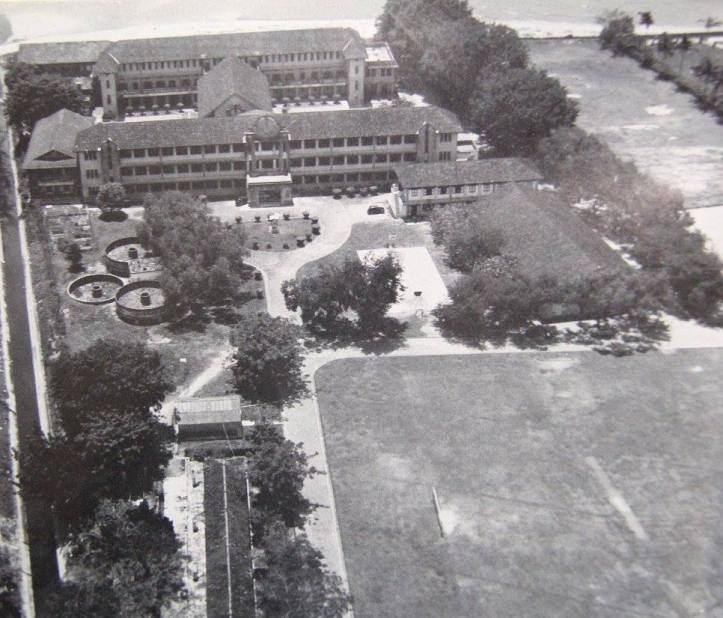

On 15 September the Wanganella arrived at Keppel Harbour on Singapore Island and berthed at Victoria Dock. Ten of the 2/13th AGH nurses were immediately detached to the 2/10th AGH and did not disembark with the others. They later entrained for Malacca, somewhat dismayed at being so abruptly separated from their new colleagues. Kath, who had now relinquished her appointment to temporary matron, and the remaining nurses, meanwhile, disembarked and in sweltering heat set off in buses for St. Patrick’s School, located in Katong on the south coast of the island to the east of Singapore city. Here the unit would be billetted until ordered to relocate to its permanent base, an unfinished psychiatric hospital at Tampoi in Johor Bahru, which lay on the other side of the Causeway from Singapore Island. The order would not come for 10 weeks.

St. Patrick’s School consisted of three large buildings, two of which were brick, and many smaller outbuildings. The beautiful grounds contained plantings of hibiscus, bouvardia, frangipani and gardenia. While picturesquely situated on Singapore Strait, the school was separated from the beach on its southern boundary by barbed wire, landmines and notices that read ‘Danger – Keep Away.’ The nurses were allocated pleasant quarters in the south wing of the school with wide balconies and views over the forbidden beach. They slept on rope mattresses under mosquito nets, and it took some time to grow accustomed to the heat and humidity.

2/4th Casualty Clearing Station

On 19 September Matron Drummond arrived at St. Patrick’s School to take charge of the 2/13th AGH nurses. Kath was marched out to the 2/4th CCS and the following day arrived at Kajang, today part of the Kuala Lumpur conurbation but then a town to the southeast of that city.

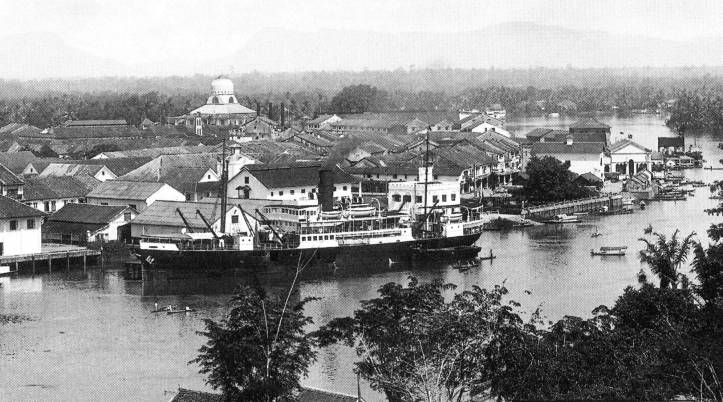

As we have seen, the 2/4th CCS arrived in Malaya in February under Lieutenant Colonel Tom Hamilton, a noted Newcastle surgeon originally from Scotland, and established its hospital in a high school in Kajang. However, the unit’s eight nurses – Sister (later Matron) Irene Drummond, Sister Mavis Hannah, and Staff Nurses Elaine Balfour Ogilvy, Millie Dorsch, Peggy Farmaner, Shirley Gardam, Mina Raymont and Bessie Wilmott – were detached upon arrival to the 2/9th Field Ambulance at Port Dickson, a coastal town 50 kilometres south of Kajang. Here they helped to establish a 50-bed dressing station for the 22nd Brigade troops, whose three battalions, the 2/18th, 2/19th and 2/20th, were based at different camps within the Port Dickson–Seremban area. The dressing station served as a first-aid post, where brigade personnel could receive attention in the event of minor injury or tropical ailment. In more serious cases, they would be transported to the 2/4th CCS at Kajang or the 2/10th AGH, which had been established in the Colonial Service Hospital in Malacca. Between May and August the nurses returned in twos and threes to the 2/4th CCS.

Soon after Kath’s arrival at Kajang the 2/4th CCS moved south to Tampoi and established a small general hospital of around 150 beds in the psychiatric hospital earmarked for the 2/13th AGH. The rambling, single-story complex had been leased from the Sultan of Johor and was ringed around by a high iron fence. In accordance with the terms of the lease, the psychiatric patients were able to remain on site in a separate building. On one side was jungle, and it was not unusual for scorpions, centipedes and other creatures to turn up occasionally in the wards. These were some distance apart and connected by long, covered concrete paths, and sometimes bicycles were ridden from one ward to another! The nurses’ quarters, surrounded by a high brick wall, were far enough from the hospital to necessitate the use of a small bus for transport.

On 14 October eight nurses arrived at Tampoi on detachment from the 2/13th AGH. There was an absence of work for them at St. Patrick’s School, and while the unit waited to move into the Tampoi site, many of its nurses and orderlies were detached on rotation to the 2/10th AGH in Malacca and to the 2/4th CCS.

Movement

In November the 2/4th CCS nurses were split up. On 12 November Mavis Hannah, Peggy Farmaner, Mina Raymont and Bessie Wilmott were detached to the camp rest station (CRS) at Segamat, 140 kilometres east of Port Dickson, where the 2/29th Battalion was based. On 14 November Kath, Elaine Balfour Ogilvie, Millie Dorsch and Shirley Gardam were sent to the CRS at Batu Pahat, 80 kilometres south of Segamat, to look after the 2/30th Battalion. By then, a further 15 nurses from the 2/13th AGH had arrived at Tampoi, for a total of 23. They took over the nursing duties of the departed 2/4th CCS nurses and, together with 2/13th AGH orderlies who had also been detached, began to prepare the way for their colleagues at St. Patrick’s School, who would soon join them.

On 20 November the 2/4th CCS began to move out of the hospital in Tampoi to a site in Kluang, 80 kilometres to the north. On that day, an advance party established the unit’s new base on the edge of Kluang’s aerodrome next to a civilian hospital, whose operating theatre the 2/4th CCS would soon made use of. The bulk of the unit arrived three days later. At the same time, the 2/13th AGH received its movement order, and over the weekend of 21–23 November the remaining staff of the unit, together with 100 tons of equipment, relocated from Katong to Tampoi in an impressive feat of logistics.

With Japanese troops now massing in French Indochina, all the signs pointed to war. On 1 December the codeword ‘Seaview’ was issued, advancing all Commonwealth forces in Malaya to the second degree of readiness. All leave was cancelled and units had to be ready to move at a few hours’ notice to their war stations. On 6 December Mavis, Peggy, Mina and Bessie arrived at Kluang from Segamat with Major Ted Fisher, a senior 2/4th CCS medical officer. Later that day the codeword ‘Raffles’ was given, indicating advancement to the first degree of readiness. At around the same time the Australian crew of No. 1 Squadron RAAF, flying out of the RAF base in Kota Bharu on the northeastern coast of Malaya, reported the presence of a Japanese fleet in the Gulf of Thailand. War was imminent.

War

It came within 36 hours. At around 12.30 am on 8 December troops from General Yamashita’s 25th Army made coordinated amphibious landings at Kota Bharu and at Pattani and Singora (Songkhla) in Thailand. At Kota Bharu the 8th Indian Infantry Brigade offered stiff ground resistance, while No. 1 Squadron RAAF bombed and strafed the landing force, but ultimately to no avail, and before long Japanese forces had established a beachhead. Meanwhile, the landings in Thailand were unopposed, and Japanese forces immediately proceeded inland. Then at around 4.30 am 17 Japanese bombers, flying from southern Indochina, attacked targets on Singapore Island, including air bases at Tengah and Seletar in the north of the island. Raffles Place in Singapore city was also hit, killing 61 people and injuring hundreds, mainly soldiers. Some of the 2/13th AGH nurses at Tampoi witnessed the attack. Elsewhere, Pearl Harbour, Guam, Midway, Wake Island and American installations in the Philippines were attacked and Hong Kong was invaded. Japan declared war on the United States, Great Britain, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa. The Pacific War had begun.

On the morning of the invasion Kath, Elaine, Millie and Shirley arrived at Kluang from Batu Pahat with Major Sydney Krantz, one of the 2/4th CCS’s three surgeons. They found the staff busy preparing to relocate to the unit’s war station at Mengkibol Estate, a rubber plantation five kilometres to the west of Kluang whose owners were away in India. In anticipation of Japanese hostilities, the site had been earmarked by Lieutenant Colonel Hamilton some days earlier.

That evening Kath and her nurses arrived at Mengkibol with their amahs (housemaids) and were assigned quarters in a comfortable, two-storey brick bungalow. Over the coming days, a casualty clearing station of more than 80 tents was erected under the lines of rubber trees, with a road dubbed ‘Kinsella Avenue’ in Kath’s honour dividing the surgical section from the medical and resuscitation tents.

The three-pronged Japanese invasion force soon began to move southwards. From Kota Bharu Japanese troops began to advance down the eastern side of the Malay Peninsula, while from Pattani and Singora the invading troops crossed into Malaya and began to advance down the peninsula’s western side. Backed by mechanized units and devastating air power, the three columns of well-trained, combat-ready Japanese troops forced severely outgunned British and Indian troops to retreat before them. Without air cover, they never had a chance.

Christmas Day arrived at Mengkibol and provided a welcome diversion from the worsening situation. Comfort Fund parcels and bottles of beer were distributed in the morning, and at 1.00 pm everyone free of routine duties sat down for an excellent dinner of pork and poultry at tables decorated with frangipani flowers and orchids gathered by the nurses from the bungalow garden. On New Year’s Eve the nurses gave an impromptu party in their bungalow and invited the officers. The younger officers stayed and enjoyed themselves, while Lieutenant Colonel Hamilton and Majors Fisher and Hobbs put in brief appearances.

The 2/10th AGH Evacuates to Singapore

By the end of 1941 it had become clear that the 2/10th AGH would have to be evacuated southwards. Kuala Lumpur had been bombed, and Malacca was now in the direct path of the Japanese advance on the western side of the peninsula. Colonel Derham decided to move the hospital to Singapore Island but would need time to find a suitable site. In the meantime, most of the staff, together with the patients, would be relocated to the 2/13th AGH at Tampoi, while the remaining staff would go to the 2/4th CCS at Mengkibol.

After Christmas Matron Dot Paschke began to send her nurses with their patients to Tampoi, a ward at a time. Soon the hospital was empty of patients, and on 8 January 1942, the final 20 nurses, including Matron Paschke herself, together with five officers arrived at Mengkibol in ambulances. Kath and her nurses greeted the new arrivals and showed them around.

Some days later, Kath took post-operative charge of an RAF flight-sergeant who had walked into a whirling propeller at Kluang aerodrome, nearly severing his arm at the shoulder. According to Lieutenant Colonel Hamilton, she “shooed the deeply interested spare orderlies from the theatre, and applied her splendid nursing technique to the task of nourishing the small spark of life left in the patient.” The patient made rapid progress and his arm was saved. Later Hamilton complimented Kath’s skill and joked that he would recommend her for a “nice comfortable job as Matron of a base hospital.” “Don’t you do any such thing, colonel,” Kath replied. “I’m quite happy where I am” (Hamilton, p. 44).

On 13 January Matron Paschke and Colonel Edward Rowden White, the commanding officer of the 2/10th AGH, drove to Singapore Island to inspect a possible site for the unit’s occupation – Oldham Hall, a Methodist boarding school on Barker Road. The school had evidently been evacuated in a hurry, and torn books, broken school furniture and rubbish filled the place. It looked at first like a lost cause, but within three days Oldham Hall was a spotlessly clean 200-bed hospital with room for many more, complete with wards, an operating theatre, a sterilizing room, a recovery room etc. Finally a nearby boarding house known as Manor House was acquired for use as the main surgical block.

Battle of Gemas

On 14 January 8th Division troops engaged Japanese forces for the first time. Shortly after 4.00 pm, B Company of the 2/30th Battalion ambushed bicycle-mounted Japanese troops at Gemencheh Bridge, around 120 kilometres north of Kluang. That night Australian casualties began to arrive at Mengkibol. Major Hobbs and his surgical team, which included Kath and Peggy Farmaner, worked throughout the night, but even so, there were fewer cases than expected. The following day was a different matter.

On 15 January the main force of the 2/30th Battalion, together with elements of the 2/4th Anti-Tank Regiment, made further contact with Japanese forces outside Gemas, 20 kilometres east of Gemencheh Bridge. That evening a convoy arrived at Mengkibol with 36 casualties, and by 6.00 am the next morning 165 cases had been admitted and 35 operations carried out, with some of the 2/10th AGH nurses sharing theatre duties with the 2/4th CCS nurses. Skirmishes continued for another day, and although the Australians scored a tactical victory, they did little to slow the Japanese advance.

The 2/10th AGH had completed its relocation to Singapore Island by the conclusion of the Battle of Gemas, and the unit’s nurses began to return from Tampoi and Mengkibol. Not only had Oldham Hall been taken over, but Manor House on nearby Chancery Lane had been requisitioned as a surgical wing.

The 2/4th CCS Withdraws Southwards

On 19 January, with no Commonwealth troops now remaining between Mengkibol and Japanese forward positions, Lieutenant Colonel Hamilton was ordered to send the nurses to the 2/13th AGH and to move the 2/4th CCS to its fallback position at Fraser Estate rubber plantation, near Kulai, around 60 kilometres south of Mengkibol, and only 20 or so kilometres north of Tampoi. In the event, the nurses ended up with the 2/10th AGH at Oldham Hall, arriving early on 20 January.

While Kath and her seven colleagues were at Oldham Hall, the 2/4th CCS continued to retreat southwards. After four days at Fraser Estate, on 25 January the unit relocated to the old psychiatric hospital at Johor Bahru (not the site at Tampoi, but another hospital on the waterfront). On 28 January the unit moved again, this time to the Bukit Panjang English School on Singapore Island. Despite these relocations, Lieutenant Colonel Hamilton’s team had treated 1,600 battle casualties since 14 January. Meanwhile, by the end of 25 January the 2/13th AGH had completed its own withdrawal, returning to St. Patrick’s School.

On 30 January Lieutenant Colonel Hamilton drove to Oldham Hall to tell Kath and her nurses that they were to rejoin the 2/4th CCS at Bukit Panjang. He found the 2/10th AGH “working at high pressure. Extra tents had been erected to take the overflow of sick from the old school buildings where it was scarcely possible to squeeze between the crowded beds” (Hamilton, p. 139). The nurses were thrilled at the prospect of returning to their unit and hastily packed their belongings. When they arrived at Bukit Panjang the orderlies greeted them with cheers, and their presence had a marked effect on the morale of the patients and the other staff.

In the early hours of 31 January the last Commonwealth troops crossed the Causeway linking the peninsula to Singapore Island. After the final man had crossed, British engineers blew the Causeway in two places in an attempt to slow the Japanese advance onto the island. The first explosion destroyed the lock’s lift-bridge, while the second caused a 21-metre gap in the structure. The breaches bought just eight days’ respite.

On that same day, 31 January, the 2/4th CCS nurses were separated again. At the request of Lieutenant Colonel J. G. Glyn White, Colonel Derham’s deputy, Mavis, Millie, Shirley and Mina had been detached to the 2/13th AGH at St. Patrick’s School. They said goodbye to Kath, Elaine, Peggy and Bessie.

The Fall of ‘Fortress Singapore’

The forces of the Japanese 25th Army were now in complete control of the peninsula and on 2 February began a ferocious artillery bombardment of the island. Despite this, while Japanese troops were held temporarily at bay by the waters of Johor Strait, Kath and her colleagues experienced a period of relative quiet at the Bukit Panjang English School. Apart from artillery casualties, admissions were confined mainly to cases of exhaustion and sickness. There were, however, plenty of other concerns for the unit. The school was located close to oil tanks and factories targeted by Japanese bombers, and some of the bombs fell close enough to the school to cause anxiety among the patients. In addition, flak from British ack-ack shells regularly fell on the school.

On 4 February a new and disturbing problem emerged for the 2/4th CCS. Japanese artillery had begun to range in on Australian artillery positions set close to the school, and stray shells caused a number of casualties. That afternoon Lieutenant Colonel Hamilton sent Kath, Elaine, Peggy and Bessie back to Oldham Hall. On 6 February the 2/4th CCS relocated to the Swiss Rifle Club, around five kilometres to the southeast. This time, though, the nurses did not return. It was around this time that one of the nearby bungalows into which the 2/10th AGH had expanded was hit by a Japanese bomb, killing a patient and an orderly.

In the daylight hours of 8 February, Japanese forces began an intensive artillery and aerial bombardment of the northwestern defence sector of Singapore Island, destroying military headquarters and communications infrastructure. That night, waves of Japanese soldiers landed in small boats around the mouth of the Kranji River on the northern coast of the island. They were initially repelled by elements of the 2/20th Battalion and 2/4th Machine Gun Battalion, but the Japanese were too numerous. They eventually overwhelmed the Australians, who could not communicate effectively with their command headquarters due to the damage caused that day, and by the morning of 9 February had established a beachhead. Further to the west there was another landing, and the end was nigh.

Tuesday 9 February was a black day indeed. Some 700 casualties poured into Oldham Hall and Manor House, where Kath, Elaine, Peggy, Bessie and their 2/10th AGH colleagues were working under increasingly difficult conditions. The hospital became so overcrowded that men were lying on mattresses on the floor while others waited outside. Many were sent on to the 2/13th AGH, where conditions were just as difficult, to the British Military Hospital (also known as the Alexandra Hospital), and to the Indian General Hospital. The theatre staff worked around the clock, treating severe head, thoracic and abdominal injuries. There was little respite for staff when they did go off duty, as the constant pounding of bombs and shells meant that sleep was hard to come by.

Evacuation of the Nurses

Reports of Japanese atrocities in Hong Kong had been circulating for some weeks, and in January Colonel Derham had asked Major General H. Gordon Bennett to evacuate the Australian nurses. Bennett had refused, citing the damaging effect on morale. Now, with Singapore’s fate all but certain, Bennett had consented, and Colonel Derham instructed Lieutenant Colonel Glyn White to send as many of the nurses as he could with Australian casualties leaving Singapore.

The nurses protested strongly; they felt duty-bound to remain with their patients, but leave they had to. On the morning of 10 February Matron Paschke picked six of her nurses to accompany perhaps 350 wounded men on the hospital ship Wusueh. Then at around 10.00 am she was informed that she must choose another 30 immediately. A ship was available but they must hurry. Matron Paschke assembled as many of her nurses as she could, divided them into two groups, and picked one of the groups. At the 2/13th AGH, meanwhile, Matron Drummond had also been asked to choose 30 of her nurses for evacuation. Later that day 60 AANS nurses boarded the Empire Star with more than 2,000 invalids and eventually set off for Batavia.

All the while, Australian, British and Indian troops were falling back towards Singapore city and the southeastern corner of the island. They were trapped like rats in a cage.

The last 65 nurses

There were now 65 AANS nurses remaining in Singapore, but they too had to leave. On the afternoon of Thursday 12 February, a convoy of ambulances carried Kath, Elaine, Peggy, Bessie and the remaining 2/10th AGH nurses from Oldham House to St. Andrew’s Cathedral in Singapore city, where a makeshift hospital had been established. There they rendezvoused with the remaining 2/13th AGH nurses and the other four 2/4th CCS nurses. During a heavy air raid, the 65 nurses’ names and numbers were recorded, then they continued towards Keppel Harbour in ambulances.

Around the port there was chaos, as people desperately tried to flee Singapore before the arrival of the Japanese. When the ambulances could drive no further, the nurses got out and walked the final few hundred metres. They passed through security checks and then waited on the wharf. Japanese planes were bombing the harbour and the city, and thick black smoke was pouring from burning oil installations on the small offshore islands.

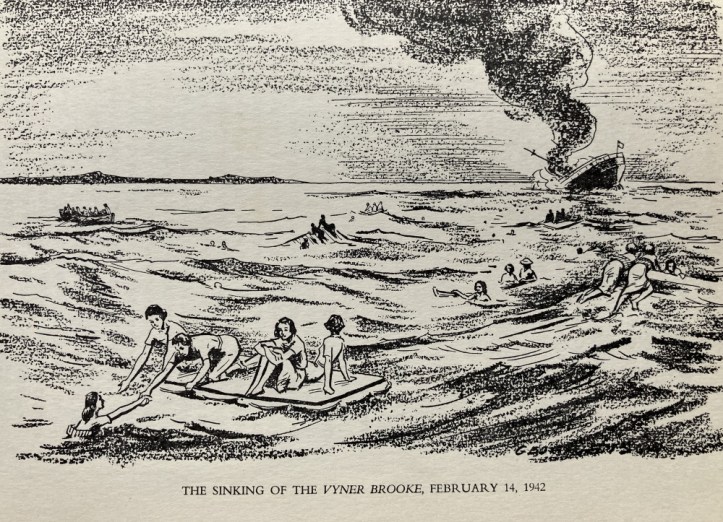

SS Vyner Brooke

Eventually a tug took the nurses out to a small coastal steamer, the Vyner Brooke, which had once been the Rajah of Sarawak’s private yacht. As darkness fell, the Vyner Brooke set off but stopped again in mid-harbour. Finally, under the cover of night, the captain, Richard Borton, negotiated the minefield protecting the harbour and steered the ship towards the Durian Strait, the first part of the journey to Batavia in Java.

There were perhaps 250 passengers on board the Vyner Brooke. Apart from the 65 nurses and a number of military personnel, they were civilians, mainly women and children, with a smaller number of older men. They were crammed into all available spaces, and each had been issued with a lifebelt.

During the night, Captain Borton guided the Vyner Brooke slowly and carefully through the many islands that lie between Singapore and Batavia, and at first light on Friday 13 February he sought to hide the vessel among them – the better to evade Japanese planes. That morning the nurses were addressed by Matron Paschke, who set out a plan to be followed should the ship be attacked. Essentially, the nurses were to attend to the passengers, help them into the lifeboats, search for stragglers, and only then leave the ship themselves. Since there were not enough places in the Vyner Brooke’s six lifeboats for everybody, if they could swim they were to take their chances in the water. They did at least have their lifebelts, and rafts would be deployed too.

In the afternoon a single Japanese aircraft flew over the ship and strafed it. Although no one was injured, the three lifeboats on the port side were holed. There would now be even fewer places available to passengers in the event of disaster.

Saturday 14 February dawned bright and clear. After another night of slow progress through the islands, the Vyner Brooke lay hidden at anchor once again. The ship was now nearing the entrance to Bangka Strait, with Sumatra to the starboard side and Bangka Island to port. Suddenly, at around 2.00 pm, the Vyner Brooke’s spotter picked out a plane. It circled the ship and flew off again. Captain Borton, guessing that Japanese dive-bombers would soon arrive, sounded the ship’s siren. The nurses, already wearing their lifebelts, put on their tin helmets and lay on the ship’s lower deck. The captain began to zig-zag through open water towards a large landmass on the horizon – Bangka Island. Soon, the bombers appeared, flying in formation and closing fast.

The planes, grouped in two formations of three, flew towards the Vyner Brooke. The ship weaved, and the bombs missed. The planes regrouped, flew in again, and this time the pilots scored three direct hits. When the first bomb exploded amidships, the Vyner Brooke lifted and rocked with a vast roar. The next went down the funnel and exploded in the engine room. As passengers swarmed up to the open air, a third bomb dealt the ship a last, fatal blow. With a dreadful noise of smashing glass and timber, it shuddered and came to a standstill, around 15 kilometres from Bangka Island.

The nurses carried out their action plan. They helped the women and children, the oldest people, the wounded, and their own injured colleagues into the three remaining lifeboats, the first two of which got away successfully. However, the Vyner Brooke was now listing alarmingly, and as the third lifeboat was being lowered it juddered and swayed and crashed awkwardly into the water. A number of its passengers jumped out and swam, for fear that the ship might fall onto them.

After a final search, it was the nurses’ turn to evacuate the doomed ship. They removed their shoes and their tin helmets and entered the water any way they could. Some jumped from the portside railing, now high up in the air, while others practically stepped into the water on the starboard side. Some slid down ropes or climbed down ladders.

Once in the water, some of the nurses managed to clamber onto rafts and some grabbed hold of passing flotsam. Others caught hold of the ropes trailing behind the first two lifeboats or simply floated in their lifebelts. Meanwhile, the Vyner Brooke settled lower and lower in the water and then slipped out of sight. It had taken less than half an hour to sink.

Lost at Sea

Twelve nurses died as a result of the attack. Among them was Kath. She was seen briefly in the water before disappearing beneath the waves.

Staff Nurse Mona Wilton of the 2/13th AGH made it into the water safely but was struck on the head by a falling raft and floated away.

Staff Nurse Mary Clarke and Sister Caroline Ennis of the 2/10th AGH, Staff Nurses Myrtle McDonald and Merle Trenerry of the 2/13th AGH, Kath’s 2/4th CCS colleague Sister Millie Dorsch, and Matron Paschke managed to reach a raft but were caught in a current and carried out to sea.

Sisters Nell Calnan and Jean Russell and Staff Nurse Marjorie Schuman, all of the 2/10th AGH, disappeared without a trace.

Finally, like Kath, Sister Vima Bates of the 2/13th AGH was seen briefly in the water before vanishing.

The remaining 53 nurses were washed ashore on Bangka Island. Twenty-one were killed in a horrific massacre on a beach, which only Staff Nurse Vivian Bullwinkel of the 2/13th AGH survived. Vivian joined the remaining 31 nurses in Japanese internment camps for the next three and a half years. Only 24 came home.

In memory of Kath.

SOURCES

- Ancestry.

- Anonymous, ‘Malaya,’ in Wellesley-Smith, A. and Shaw, E. L., eds. (1944), Lest We Forget, Australian Army Nursing Service.

- Australian War Memorial, Unit War Diaries (1939–45 War), 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station Malaya, Oct 1941–Feb 1942, AWM52 11/6/6/4.

- Hamilton, T. (1957), Soldier Surgeon in Malaya, Angus & Robertson.

- Jeffrey, B. (1954), White Coolies, Angus & Robertson Publishers.

- Narre Warren & District Family History Group Inc., ‘Sister Kath Kinsella.’

- The National Archives (UK), ‘Kinsella, Nancy May,’ WO 373/83/729.

- National Archives of Australia.

- Nelson, H. (2007), ‘Australian Prisoners of War 1941–1945,’ Anzac Portal, Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Australian Government.

- Simons, J. E. (1956), While History Passed, William Heinemann Ltd.

- Jeffrey, B., ‘A Tribute to Matron O. D. Paschke R.R.C.,’ Una Nursing Journal (Vol. XLVI, 2 Feb 1948, pp. 37–39), Australian Nursing Federation.

- Walker, A. B. (1962), Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 5 – Medical, Vol. II – Middle East and Far East, Part II, Chap. 23 – Malayan Campaign (pp. 492–522), Australian War Memorial.

- Wikipedia, ‘Bombing of Singapore (1941).’

SOURCES: Newspapers

- The Dandenong Journal (Vic., 26 Jul 1944, p. 10), ‘Sad News For Cr. D. L. Kinsella.’

- The Dandenong Journal (Vic., 24 Mar 1948, p 10), ‘Yannathan.’

- The Herald (Melbourne, 11 Dec 1928, p. 27), ‘New Nurses.’

- The Pastoral Times (South Deniliquin, NSW, 17 Mar 1942, p. 1), ‘Nurse’s Thrilling Story.’

- The Swan Express (Midland Junction, WA, 15 Feb 1945, p. 5), ‘We Sailed for Singapore.’