AANS │ Sister Group 2 │ Second World War │ Malaya │ 2/13th Australian General Hospital

EARLY LIFE

Ada Joyce Bridge, known as Joyce, was born on 6 July 1907 in Scone, New South Wales. She was the daughter of Ada Matilda Thurlow (1878–1957), from Scone, and William Thomas Bridge (1869–1938), who was born at Blue Gum Flat (now Ourimbah), near Gosford in New South Wales.

Ada and William were married in 1903, and their son, Leslie Thurlow Bridge, was born two years later, in 1905. Joyce followed in 1907.

The Bridge family lived at Stoney Creek, a 2,698-acre sheep property at Belltrees, 30 kilometres to the east of Scone. William was a highly respected member of the community and became a Shire Councillor. Ada was a prominent member of the Belltrees Red Cross Society and participated in many social and charitable fundraising activities.

In One Life Is Ours – The Story of Ada Joyce Bridge, Joan Crouch wrote that as a young girl, “Joyce loved the country life at Stoney Creek. She and her brother rode their horses three miles to attend the Public School at Belltrees until they reached sixth class” (Crouch, p. 5).

“Joyce was socially very popular,” continued Joan. She was “an excellent dancer [and] enjoyed the local dances in Scone and surrounding district. She was a good horsewoman, and loved helping her father and brother with the sheep and cattle work on the property.” Joyce played tennis too and “spent time with her friends at weekend tennis parties” (Crouch, p. 5).

NURSING

Joyce became a caring and compassionate person with a desire to help others and a strong sense of responsibility, and in time decided to become a nurse. She applied to St. Luke’s Hospital in Darlinghurst, Sydney, was accepted, and began her training on 1 February 1930. First, however, she had to sit the Nurses’ Entrance Education Examination, as she had not attained her Intermediate Certificate at school.

Joyce went straight onto the wards, worked long days, and soon settled into a routine. She struck up lasting friendships, with one colleague recalling many years later that she was “a genuine friend, a typical country girl, who took pride in her work and was a very good nurse.”

Joyce successfully sat her final nurses’ examination on 6 May 1934 and gained her registration on 6 September. She stayed on at St. Luke’s as a staff sister and after a time left to join Toshack’s Nursing Club on King’s Cross Road, undertaking nursing at various private hospitals in the area. During this time, she shared a flat with her friend Joyce Boyd and later with her friend Millicent Martin.

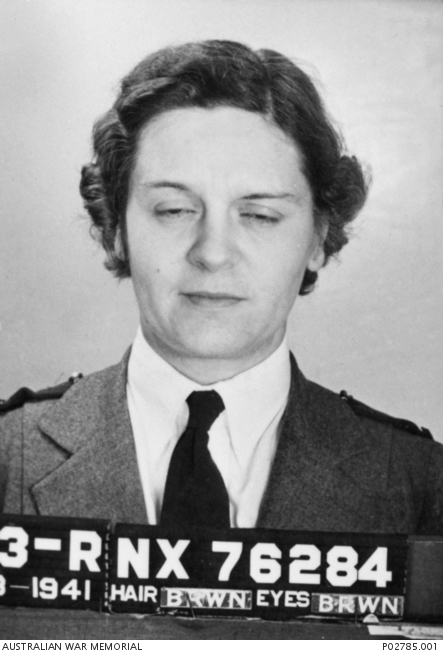

ENLISTMENT AND EMBARKATION

When war broke out in Europe, Joyce and Millicent volunteered together. Unfortunately, Millicent’s marriage in 1940 ended her eligibility. Joyce proceeded with her enlistment and in April 1941 was appointed to the Australian Military Forces for home service with the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS).

Four months later, on 18 August, Joyce was appointed to the Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF) for service abroad with the AANS. She was attached to a new Australian medical unit, the 2/13th Australian General Hospital (AGH).

The 2/13th AGH had been raised in Melbourne in early August on the recommendation of Col. Alfred Derham, officer in charge of Australia’s medical units in Malaya. The unit would join the 2/10th AGH and the 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station (CCS), both of which units had sailed to Malaya on the Queen Mary in February. Neither Joyce nor any other 2/13th AGH appointee would know their destination until shortly before arrival in Singapore.

Following her enlistment, Joyce was briefly detached to the camp dressing station at Tamworth before going on embarkation leave. On 30 August the day of departure arrived. Joyce, 18 other Queensland and New South Wales AANS nurses, and half-a-dozen other staff of the 2/13th AGH embarked on Australian Hospital Ship (AHS) Wanganella and set out for Melbourne.

On 1 September, AHS Wanganella arrived at Port Melbourne. Following the embarkation of 24 Victorian, South Australian and Tasmanian AANS nurses and around 180 other 2/13th AGH personnel, the ship set out again on 2 September. A final stop in Fremantle saw the embarkation of seven more AANS nurses and one disembarkation. There were now 49 AANS nurses aboard.

It was only after the Wanganella departed Fremantle on 9 September that the 2/13th AGH staff officially learned that their destination was Malaya. They arrived at Victoria Dock on Singapore Island on 15 September.

MALAYA

Joyce and nine of her new colleagues were detached immediately to the 2/10th AGH and entrained for Malacca on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula. The remaining 39 nurses were transported in sweltering heat to St. Patrick’s School at Katong on the island’s south coast, where the 2/13th AGH was to be based for the time being.

The 10 nurses arrived at the 2/10th AGH in Malacca the next morning, somewhat resentful at being so abruptly separated from their 2/13th AGH colleagues. However, rolling detachments to the 2/10th AGH and to the 2/4th CCS at Tampoi would be the pattern for the next two months. There was as yet no work for the 2/13th AGH nurses in Singapore, and through their detachments to the other two units they would learn tropical nursing from their more experienced colleagues.

After three weeks in Malacca, Joyce returned to the 2/13th AGH at Katong. She was posted to Malacca again on 19 November. It was while she was there that the Pacific War began.

JAPAN INVADES

Soon after midnight on 8 December, a force of some 5,000 troops of the Imperial Japanese Army launched an amphibious assault at Kota Bharu on the Malay Peninsula’s northern coast. Four hours later, 17 Japanese bombers attacked Singapore Island.

Not for a minute did the nurses think that the Japanese could possibly reach as far south as Malacca, due to the primitive roads and great tracts of jungle and rubber plantation, and due to perceived Japanese inadequacies. Many years later, Betty Pyman of the 2/10th AGH recalled that “everyone said, ‘The Japanese haven’t got this, and they haven’t got that, they haven’t got the other thing,’ so we were absolutely staggered when we had to get out.”

Jessie Blanch of the 2/10th AGH made the same observation. “We were told by our spies that [the Japanese] all wore glasses and couldn’t see at night,” she wrote. “They weren’t supposed to be able to do anything” (quoted in McCullagh, p. 111).

Hence, when Joyce returned to the 2/13th AGH on 13 December she was likely not especially perturbed. By this time the unit had moved into a psychiatric hospital in Tampoi, southern Johore, leased from the Sultan of Johore. The hospital had previously been occupied by the 2/4th CCS, which had relocated north to Kluang.

However, over the next nine weeks, Japanese infantry, backed by mechanized units and substantial sea and air power, surged down the Malay Peninsula in three lines of attack at a steady pace of 15 kilometres a day, forcing severely outgunned British and Indian troops to retreat southwards. Japanese inadequacy had proved an illusion.

The 8th Division’s entry into combat on 14 January did little to stop the Japanese advance, and soon the Australians were retreating too. The 2/13th AGH returned to St. Patrick’s School on 25 January 1942. The 2/10th AGH had relocated to the island 10 days earlier and the 2/4th CCS would follow three days later. By 31 January all Commonwealth troops had retreated to Singapore Island.

When Japanese forces crossed Johore Strait on the night of 8 February and established a beachhead on the island, the end was nigh. Pressure mounted on 8th Division headquarters to evacuate the nurses, and on 10 February the first six nurses embarked with 300 wounded on the makeshift hospital ship Wusueh. The following day a further 60 AANS nurses, drawn from both AGHs, boarded the Empire Star with more than 2,000 evacuees, mainly British army and naval personnel, and set out for Batavia. Finally, on Thursday 12 February, Joyce and her 64 remaining colleagues had to go too.

The VYNER BROOKE

The 65 nurses were driven to Keppel Harbour in ambulances and ferried out to the small coastal steamer Vyner Brooke, lying at anchor in the harbour. On board were as many as 200 people – women, children, old and infirm men. As darkness fell, the ship slipped away and began its journey south. After a night and a day of little progress, by Saturday afternoon the Vyner Brooke had barely reached the mouth of Bangka Strait, a strip of water that separates Sumatra and Bangka Island.

Suddenly, at around 11.00 am, a Japanese plane swooped over, then flew off again. At around 2.00 pm another plane approached before flying off. Captain Borton anticipated the arrival of Japanese dive-bombers and sounded the ship’s siren, then began a run through open water. When a squadron of dive-bombers appeared on the horizon, Borton commenced evasive manoeuvres.

The bombers approached, and the Vyner Brooke zigzagged wildly at full speed. The first wave of bombs missed their target. The planes banked, lined up again, and came in for a second run. One bomb struck the forward deck, another entered the ship’s funnel and exploded in the engine room, and a third tore a hole in the hull. The devastated ship began to sink, 15 kilometres from Bangka Island.

After helping passengers and their own injured colleagues into the three viable lifeboats, the nurses abandoned ship. Joyce found herself in the water amid the wreckage, dead bodies and fetid oil and managed to clamber aboard or trail behind one of the lifeboats. Or perhaps she clung to a raft or a piece of wreckage, or simply floated in her lifebelt.

BANGKA ISLAND

Regardless of how she got there, Joyce made it ashore in the vicinity of Radji Beach and joined a growing group of survivors around a bonfire. By Monday morning, 21 of her colleagues were with her. The group, which now numbered 80 or so, decided to surrender to Japanese authorities, and a deputation left for the nearest large town, Muntok, to negotiate this. A short while later all the civilian women and children of the group followed behind – save one, Mrs. Betteridge, a British woman whose husband lay among the injured on the beach.

Some hours later the deputation returned with a party of Japanese soldiers. The soldiers separated the survivors into three groups and proceeded to shoot or bayonet them in cold blood.

Joyce and 20 colleagues died on Bangka Island on Monday 16 February 1942. They were shot while standing in the sea. Only Vivian Bullwinkel survived.

Three-and-a-half years later, 24 nurses were rescued from the depths of the Sumatran jungle, where they had been interned by the Japanese, and on 16 September flown to Singapore. They were the only survivors of the party of 65 that had set out that fateful day in February 1942. Twelve were lost at sea when the Vyner Brooke was attacked. Eight died in captivity. And 21 died on Radji Beach. The nurses were interviewed upon arrival by Australian journalists, and the following day Vivian Bullwinkel was quoted at length in the Australian press. “We all knew we were going to die,” she said of that shocking day. “We stood waiting. There were no protests. The sisters died bravely, and their marvellous courage prevented me calling out when I was hit. I couldn’t let them down.”

In memory of Joyce.

SOURCES

- The Armidale Express and New England General Advertiser (17 Sep 1945, p. 1), ‘Australian Nurses’ Heroism.’

- Crouch, J. (1989), One Life Is Ours: The Story of Ada Joyce Bridge, Nightingale Committee, St. Luke’s Hospital. (NB. I have relied heavily on this text for the early part of Joyce’s life and have used sections verbatim and without quotation marks.)

- Jeffrey, B. (1954), White Coolies, Angus & Robertson Publishers.

- McCullagh, C. (ed., 2010), Willingly into the Fray: One Hundred Years of Australian Army Nursing, Big Sky Publishing.

- National Archives of Australia.

- Shaw, I. W. (2010), On Radji Beach, Pan Macmillan Australia.

- Simons, J. E. (1954), While History Passed, William Heinemann Ltd.

- University of NSW, Canberra, Australians at War Film Archive, ‘Elizabeth Bradwell (Betty Pyman) – Transcript of interview, 19 January 2004.’