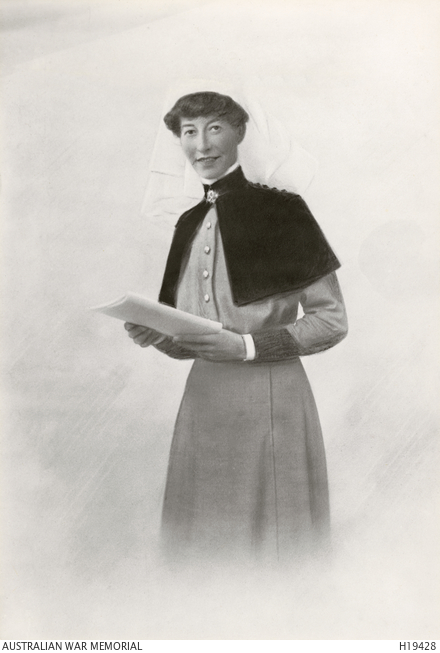

AANS │ Matron │ First World War │ Egypt, England, France & HMHS Gascon

FAMILY BACKGROUND

Jean Nellie Walker was born on 16 November 1878 at Forth, near Port Sorell in Tasmania. She was one of 10 children born to Louisa Mary Glover Wilkinson (1841–1926) and Alfred Miles Walker (1829–1881).

Louisa Wilkinson was born in Forth, Tasmania. Her father, Dr. Frederick Belmore St. George Wilkinson of Torquay (which, together with Formby, became the town of Devonport), had been an army surgeon in the Crimean War.

Alfred Walker, whose parents had migrated from Wales, was born at the family estate of ‘Vron’ on the Liffey River near what is today Bishopsbourne, Tasmania.

Louisa and Alfred were married on 23 May 1866 at Louisa’s family home at Torquay by the Rev. Charles Martin. They lived in the district of Forth, where Alfred was a farmer. In 1867 Louisa gave birth to the couple’s first child, Louis Augustine William Walker, and over the next 13 years gave birth to nine more. Jean was the second youngest.

In August 1877 Alfred was declared insolvent and became a storekeeper. The following month, the family underwent a terrible tragedy, when four of their children – Rhoda, George, Nellie and Alfred (these last two twins) – died within a week of each other, the result of diphtheria, which was rampant in the area at the time. When Alfred died four years later, Louisa was left to carry on with six children.

NURSING

Time went by, and Jean became old enough to begin her learning. She was privately educated until 1893 and then enrolled at the Collegiate School in Hobart, which had been established in 1892 by an Anglican order of nuns. After finishing school, Jean decided to go into nursing (as would all her sisters), and in 1903 began training at the Hobart General Hospital under Matron Turnbull. She completed her training in 1906 and in that same year joined the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS), 6th Military District (Tasmania).

The AANS was established in each state in 1902 following the Second Boer War, during which around 60 Australian nurses served in colonial units. Nurses selected to join the AANS were issued with certificates of efficiency and were expected to attend parades held four times a year, at which lectures on military nursing were given and practical first aid demonstrated. If a nurse did not attend the required number of parades her certificate would not be signed as efficient.

After the completion of her training at Hobart General, Jean stayed on as a staff nurse and later senior sister. In November 1908 she tendered her resignation to take up private nursing in Hobart. Meanwhile, she maintained her efficiency status with the AANS, and on 5 April 1909 was appointed Matron, AANS, 6th Military District.

In time, Jean moved to Melbourne either to take up an appointment at the Women’s Hospital or to train there in midwifery, or both – sources differ. In any case she finished at the Women’s in 1913 and by September of that year was working as matron at Nalinga Private Hospital, on Wagra Street in Tallangatta, northeastern Victoria. In 1914 Jean moved to Sydney and worked at Molong Private Hospital on Forbes Street in Darlinghurst.

MOBILISATION

On 5 August 1914 Australia went to war. Prime Minister Joseph Cook had already promised to send an expeditionary force of 20,000 men to wherever they were needed, and now plans were drawn up to transport them. With the troops would travel numerous medical units and a contingent of nurses.

After applications were sought from among the nurses of the AANS reserve, Jean applied on 10 September under the name Jean Miles Walker, adopting her father’s middle name as her own middle name. Soon it would form part of her surname, which was sometimes hyphenated.

Jean’s application was accepted and on 21 September she joined the AANS, Australian Imperial Force at the rank of Sister. She was one of 25 AANS nurses to be chosen on the basis of ‘efficiency’ and seniority, five of whom were Second Boer War veterans, including Ellen Julia (Nellie) Gould, who would lead the contingent as Principal Matron.

As part of Jean’s application, she had provided a reference attesting to her competency and health from Dr. Stratford Sheldon of Molong Private Hospital, which stated simply that Jean was “quite competent in all branches of nursing (being in charge of above hospital).”

Mobilisation began in September. The 25 nurses would sail from their respective states with elements of the 20,000-strong, all-volunteer expeditionary force. The seven troopships in which the nurses would travel would converge in Albany, Western Australia and await a further 21 troopships carrying the balance of the expeditionary force. Joining the Australian ships would be 10 New Zealand troopships carrying 10,000 men.

HMAT EURIPIDES

Along with Principal Matron Gould and Sisters Julia Bligh Johnston, (Adelaide) Maud Kellett, Alice Joan Twynam and Penelope Frater, Jean was detailed for duty on board His Majesty’s Australian Troopship Euripides. She and the others were told to be ready to sail on 29 September for an unknown destination. On the day of departure Principal Matron Gould was informed that embarkation was indefinitely postponed – due, as it turned out, to the presence of the German raider Emden somewhere in the Indian Ocean.

Jean and her colleagues remained on call until 19 October, on which day they were instructed to come to Circular Quay. They were taken across the harbour in a motor launch, arriving at the Euripides in time for lunch. They were met by the captain and shown to their accommodation, two comfortable and airy cabins, each with three berths, plus a private sitting room. They were also assigned a stewardess to look after their needs.

At 6.00 pm the siren sounded and the Euripides weighed anchor and set off amid much cheering and much noise from the sirens of the boats in the harbour. However, the ship only got as far as Watson’s Bay (or Bradley’s Head – sources differ), still within the Harbour, before casting anchor for the night. Finally, at 6.30 am the following morning, 20 October, the Euripides was off in real earnest. It passed through the Heads to the accompaniment of shrieking siren calls from the early ferry steamers and sailed south into rough seas.

On board the six nurses prepared three wards plus an overflow ward on the poop deck. While the orderlies made the beds, the nurses got ready for an influx of patients, as a severe form of influenza had been brought on board, with some cases developing pneumonia. During the course of the voyage, they also treated boils, eye infections, ear troubles, septic fingers, and colds. Two soldiers with appendicitis were operated on, one more serious than the other.

The Euripides sailed south along the coast of New South Wales, through Bass Straight between Victoria and Tasmania, past South Australia, and at noon on 26 October steamed slowly to an anchorage in King George’s Sound, the harbour of Albany, and waited. Much to the nurses’ disappointment, they were not permitted shore leave.

On 1 November – All Saints’ Day – the great fleet of 38 Australian and New Zealand transport ships, escorted by seven warships, sailed out of King George Sound. On 9 November one of the escort ships, HMAS Sydney, engaged the Emden and put it out of action once and for all, killing a third of its crew and capturing the rest. On 13 November the convoy crossed the Equator and two days later arrived in Colombo, Ceylon. Unfortunately, once again the nurses were not permitted to go ashore. They did take a great interest, however, in the many small boats that swarmed the convoy, from which local vendors were selling all manner of things.

ARRIVAL IN EGYPT

The convoy departed Colombo on 17 November 1914 and reached Aden on 25 November. It was only now that Jean and her companions learned that they were bound for Egypt; they had expected to sail to England. They left Aden the following day and arrived at Suez on 1 December, then Port Said on 2 December and finally Alexandria at 11.00 am on 3 December. Disembarkation of the troops from the Euripides commenced at 9.00 pm that night and continued into the following day. During the crossing a severe outbreak of poisoning had laid low many of the men. Those who had not yet recovered stayed on board while their comrades entrained for Cairo and encamped at Mena, in the shadow of the Pyramids, 10 kilometres to the west of the great city. The troops from the other ships joined them, and Mena Camp became a sea of tents and soldiers.

Back on the Euripides, Matron Gould received a request on 4 December for one of her nurses to accompany the sickest of those soldiers who had remained on board to No. 19 (British) General Hospital (GH) in Alexandria, housed in the Deaconesses’ Hospital. Jean was assigned the task and that evening left the ship. The others were saddened to see her go, as they had hoped to keep together.

On the morning of 5 December Jean’s five colleagues disembarked and with the remaining 60 patients from the Euripides joined an ambulance train for Cairo. Upon arrival at around 3:30 pm they were met by British officers and told their destination would be Mena House, a luxury hotel and former royal hunting lodge located close to the Australian encampment. They arrived towards evening to find a temporary British hospital established in the hotel with Miss Greigson installed as matron. The Australian nurses made sure their own 60 patients were comfortable and went on duty the next morning.

Over the coming days, Nellie Gould, Julia Johnston, Maud Kellett, Alice Twynam and Penelope Frater were joined at Mena House by most of the other 25 AANS nurses, while the remainder were detailed for duty at the Egyptian Army Hospital at Abbassia, in eastern Cairo, where New Zealand soldiers were treated.

After some weeks at No. 19 GH in Alexandria, Jean returned to Cairo and rejoined her colleagues at Mena House.

No. 2 AUSTRALIAN GENERAL HOSPITAL

On 14 January 1915, HMAT Kyarra arrived at Alexandria. The ship had departed Fremantle on 14 December 1914 and was carrying staff and equipment of No. 1 Australian General Hospital (AGH) and No. 2 AGH, including around 180 AANS nurses. On 20 January, 96 sisters and staff nurses of No. 2 AGH arrived at Mena House. Lt. Colonel Martin, the commanding officer, soon had the hospital running like clockwork, and by the end of the month Nellie Gould had taken over as matron of No. 2 AGH.

Meanwhile, No. 1 AGH, whose matron was Jane Bell, established its hospital at the Heliopolis Palace Hotel on the eastern outskirts of Cairo, 23 kilometres away from Mena House. The Queensland, Victorian and Western Australian nurses of the original contingent of 25 were attached to No. 1 AGH and transferred from Mena House to Heliopolis.

For more than four months things were quiet at Mena House and at Heliopolis. Then, following the Gallipoli landings of 25 April, Matron Gould was given 24 hours’ notice to get ready for the arrival of over 1,500 wounded. She was also tasked with preparing a second hospital for the unit, at the Ghezireh Palace Hotel in central Cairo.

According to Maud Kellett, there was great excitement at Mena House when the first wounded arrived. These were the less severe cases, but soon the hospital received more serious cases, and before long 600 had arrived. Meanwhile, Ghezireh had received 850 casualties. Matron Gould shuttled between the two hospitals. When she was at Ghezireh, Jean was in charge at Mena House. And when she was at Mena House, Julia Johnston was in charge at Ghezireh. “Never Matron had better assistance,” Nellie Gould later wrote of Jean and Julia in her unit diary.

Across May the staff at Mena House were gradually transferred to Ghezireh, which became No. 2 AGH’s main hospital. While still not ideal, the building’s spaces were better than those of Mena House, which remained an overflow hospital for a while before being shuttered, to reopen in August.

HMHS GASCON

On 2 September 1915 Jean, Penelope Frater, Maud Kellett and Alice Twynam, greatly excited, left Cairo for Alexandria aboard the midday train. They were being posted to a British hospital ship. They were met at the station in Alexandria by an ambulance and taken to His Majesty’s Hospital Ship Gascon, where Colonel Edward V. Hugo, the commanding officer, made them welcome.

The Gascon was one of many Allied hospital ships transporting casualties from the Gallipoli Peninsula to hospitals in Egypt, Malta and England via the island of Lemnos, which lay only 100 kilometres from the Gallipoli Peninsula. After wounded soldiers received first aid on the beaches of the peninsula they were carried to barges, then transported to hospital ships lying at anchor off the coast, clear of Turkish artillery, and finally carried to Lemnos for disembarkation or onward passage.

The four AANS nurses were replacing four others whose stints had ended, Sophie Hill Durham, Clementina Hay Marshall (one of the original 25), Katherine Minnie Porter and Muriel Leontine Wakeford. These four were very sad at leaving, as they had been on the Gascon since the Gallipoli landings. Five other AANS nurses, Elsie Maud Gibson, Alice Elizabeth Barrett Kitchin, Ethel Alice Peters, Hilda Samsing (another of the original 25) and Ella Jane Tucker, had not yet finished their postings and remained with the ship.

On the morning of 5 September the Gascon departed Alexandria for Lemnos. On board were the nine AANS nurses, a British matron, four medical officers, Colonel Hugo, and various assistants and orderlies. The matron showed Jean and the three other newcomers around the hospital and detailed each to her respective ward.

The Gascon arrived at Mudros Harbour on Lemnos at 7.30 pm on 7 September and proceeded to Anzac Cove the following day. It dropped anchor at around 10.30 pm after a voyage of some six hours. For three days wounded and sick patients were embarked via barges from the beaches, and after the ship reached capacity on the night of 12 September, it left Anzac Cove to return to Mudros Harbour.

Jean and her colleagues arrived back at Mudros at 6.30 am the next morning. After a number of infectious cases were taken ashore in the afternoon, they set out for Malta that same evening, reaching Quarantine Harbour, Valetta, on the morning of 16 September. While the nurses were granted shore leave, 465 patients were disembarked.

After leaving Malta the next morning, the Gascon reached Mudros Harbour early on 20 September before departing the following day for Cape Helles on the southern tip of the Gallipoli Peninsula. It arrived at 7.00 pm and anchored close to the torpedoed ship Majestic, which was lying keel upwards and resembled, according to Maud Kellett, a huge whale.

On 22 and 23 September the Gascon took on wounded and sick, including many dysentery cases, all more or less jaundiced. The ship sailed again at 9.30 am on 24 September and reached Mudros at 2.00 pm. The following morning 309 patients were transferred to the Ausonia, which was leaving for England, and a further 208 patients were transferred to a hospital on Lemnos.

Jean and the others set out once again for Anzac Cove on the morning of 26 September. The ship arrived in the afternoon and over the next two days embarked 476 patients, mostly dysentery, some very serious, before returning to Mudros Harbour on the night of 28 September.

The following morning the Gascon received orders to proceed to Malta, and after disembarking 31 patients, got underway at 1.00 pm. The sea was so rough that the nurses had to stuff into the cupboards of mixtures and surgical things and tie the dressing tables to supports in the ward with bandages. To make things worse, most of the patients and many of the orderlies were seasick.

After the ship arrived at Quarantine Harbour on the morning of 2 October, the staff learned that the hospitals in Malta were full and they would have to proceed to Gibraltar. Forty patients were disembarked, and the following day the Gascon departed with the remaining 400.

After experiencing more rough weather, the ship entered Gibraltar’s inner harbour at 7.00 am on 8 October and immediately began to disembark its 397 patients. The following day, while the Gascon was being coaled, Jean and the others enjoyed some well-earned shore leave. They crossed the bay to the Spanish city of Algeciras and spent an enjoyable day shopping and sightseeing.

The Gascon departed Gibraltar at 7.00 am on 10 October for the return trip to Lemnos. However, a wireless message was received three days later instructing the ship to head to Malta instead, and it put in at the Grand Harbour in Valetta on the morning of 14 October. An order then came through to embark patients for England, and at around 3.00 pm on 15 October, the ship set out for Southampton with 393 patients on board, mostly convalescents and walking cases.

Throughout the voyage there was constant grumbling from the patients about the poor quality and quantity of food. Jean’s colleague Alice Kitchin, concurring, wrote in her diary about the monotony of the diet, noting bad butter and sloppy rice.

The ship arrived in Southampton on 24 October, and after disembarking its patients sailed on to London, arriving at East India Dock at 4.30 pm on 26 October. The Gascon remained in dock undergoing repairs and a refit until 10 November, and in the meantime Jean and the others enjoyed two weeks’ leave.

The Gascon left London on 11 November. It was transporting the equipment and personnel of No. 29 GH, consisting of 34 officers and 201 other ranks, to Salonika in neutral Greece, where Allied forces had begun to arrive in October in aid of Serbia. Unfortunately, the Allied troops had not been equipped for a winter campaign in difficult mountain terrain, and by the end of November, more than 1,600 men had been evacuated, many suffering from frostbite.

The ship arrived outside Salonika Harbour on the night of 25 November and entered the following day, joining a queue of hospital ships awaiting the embarkation of their assigned wounded. Snow lays on the hills beyond the city, the weather was freezing and fog shrouded the harbour. Finally 75 patients were embarked on 4 December and another 291 the following day, many suffering from trench fever, frostbite and gangrene. On the same day the 29th BGH began its disembarkation and did not conclude until late morning on 7 December. That afternoon the Gascon sailed for Alexandria, arriving early on the morning of 10 December.

When the Gascon set out again on the afternoon of 12 December, Jean, Alice Kitchin and Hilda Samsing were not aboard. Their postings had finished and they had returned to their respective hospitals in Egypt – Jean to No. 2 AGH at Ghezireh and Alice and Hilda to No. 1 AGH at Heliopolis.

No. 1 AUSTRALIAN STATIONARY HOSPITAL, ISMAILIA

On 22 January 1916 Jean was attached to No. 1 Australian Stationary Hospital (ASH) and appointed temporary matron. The unit, under the command of Colonel Henry Arthur Powell, was housed in a former French convent in the city of Ismailia on the Suez Canal. Jean was well liked and respected by her staff and helped them to cope with the isolation and extreme climate, due to which many of the nurses suffered from general debility.

The Battle of Romani, which took place in early August, saw many casualties brought to No. 1 ASH, and later General Archibald J. Murray of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) mentioned Jean in his despatch dated 1 October for her distinguished service during this time. Her Mention in Despatches was promulgated in the London Gazette on 1 December and in the Commonwealth of Australia Gazette on 19 April 1917.

The success of EEF operations against Ottoman forces in the Suez Canal area reduced the need for No. 1 ASH to remain at Ismailia, and plans were drawn up to move the unit to England. On 4 September Jean was attached to No. 15 GH in Alexandria on a temporary basis and on 25 September sailed with other members of No. 1 ASH from Alexandria to England on the Karoola.

England

After arriving, Jean spent three days with No. 2 Australian Auxiliary Hospital (AAH) at Southall, Middlesex before being attached on 8 October to No. 3 AAH – the relocated and renamed No. 1 ASH – at Dartford in Kent and appointed matron.

On 1 January 1917 a further honour was bestowed upon Jean, when she was awarded the Royal Red Cross (RRC), First Class for her exemplary services to military nursing. Extraordinarily, of the original 25 nurses, 16 were awarded either the RRC, First Class or the RRC, Second Class. There were also three CBEs and an MBE. Jean was presented with her award on 4 February by the King himself and, by request of Queen Alexandra, afterwards attended at Marlborough House.

Time passed, and on 1 July the matron-in-chief of the British Expeditionary Force in France and Flanders, Maud McCarthy (who had trained at the Coast Hospital in Sydney), sent a request to the Director General of Medical Services asking that Jean and other senior nurses be sent to France as soon as possible to take over British medical units currently nursed by the AANS. On 10 July Jean received an order to take up duty with No. 5 Stationary Hospital (SH) in Dieppe.

France

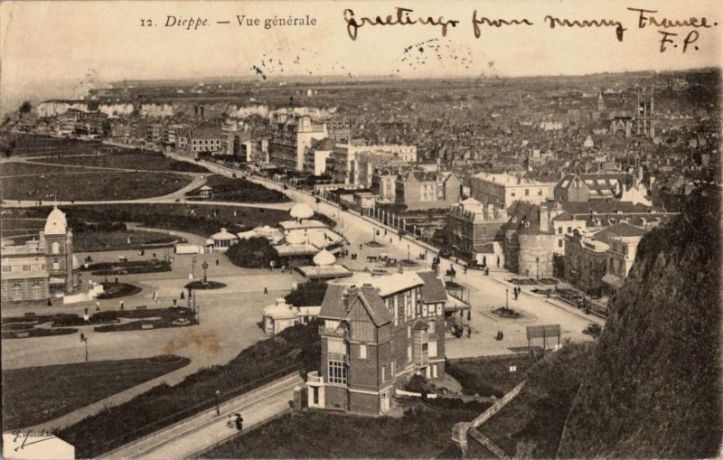

Jean crossed the Channel and on 13 July 1917 reported for duty at A Section, No. 5 SH in Dieppe to take up her appointment as matron. (B Section, No. 5 SH was located in Abbeville, 60 kilometres northeast of Dieppe.)

Dieppe was an attractive, hilly town on the Normandy coast. Its casino and several seafront hotels had been taken over by British military authorities to be used as hospitals or convalescent homes. Despite the war, life carried on; shops were open, and the shingle beach was a hive of activity.

No. 5 SH comprised four long huts, each divided into two wards. Hut one housed the acute cases, surgical one end, medical the other. Huts two and three were medical. Hut four was used to billet some of the nurses. In addition there was an officers’ ward, divided into four, a skin ward, and various huts for convalescents. The hospital was beautifully kept, with spotless huts, polished floors and white covers for the beds and lockers. Although the nursing staff at Dieppe was Australian, the medical officers and orderlies were English.

One of Jean’s nurses was a Victorian by the name of Elsie Tranter, who joined No. 5 SH on 16 July and kept a diary. In her entry of 28 July, she noted that there were more orderlies than patients in the hospital, and of the patients, none was seriously wounded. Consequently she found the nurses’ work “most uninteresting, merely probationer’s work.” Another of Jean’s nurses, Blodwyn Williams, noted similarly in her nurse’s narrative of 1919 that the work was very light at Dieppe as the hospital received mainly local cases.

On the other hand, a lighter workload meant more time for recreation. The nurses availed themselves of nearby golf links and tennis courts and spent time walking and taking local tours. In August Jean and her staff moved into new billets, Villa Marguerite, a beautiful old house set in a lovely garden and situated not far from the hospital. Jean even managed to acquire a terrier named Jack.

Staff Nurse Leila Brown, who was posted to the hospital from March to June 1918, painted an attractive picture of No. 5 SH in her 1919 nurse’s narrative:

Here we were billeted in a charming house and had everything one could wish for to make life happy. We had a ‘Tommy’ as cook and you could not have recognised Army Rations in the excellent dinners he served up every night. Here for the first time I worked the hours generally set in Aust. Hospitals that is: – one whole day per week off duty, and alternate long & short days. There was a golf course nearby & I was able to play quite often, there was also a tennis court built us by a French Baron who owned a house close to ours, and if we brought visitors to the house the late Miss Miles-Walker who was Matron welcomed them and made the atmosphere quite that of a home.

On 7 September 1917 Jean was appointed matron of No. 3 AGH at Abbeville, replacing Grace Wilson, who proceeded to AIF headquarters in London the following day to take up duty as acting matron-in-chief of the AANS.

No. 3 AGH had four principal wards in huts for serious cases, either surgical or gassed patients, as well some minor wards under canvas for less serious cases. As it was closer to the front line, the hospital was much busier than the 5th SH. When Jean was visited by Matron McCarthy on 16 October, there were 98 nurses on staff looking after 1,040 sick and wounded patients. November was a very heavy month, with 2,058 admissions in total, while December eased off a little. In January 1918 nursing was difficult due to the weather conditions, and no doubt Jean was happy to take leave from 14 January to 6 February in the south of France.

As of the end of February, there were 94 nursing staff at No. 3 AGH, comprising Jean as matron, three head-sisters, 30 sisters and 60 staff nurses, and admissions were 950. Much to Jean’s credit, it was noted in a report sent to Matron McCarthy that conduct and discipline at the hospital were excellent. During recreation time hockey matches were organised against other units, and bridge, chess, euchre and ping-pong were played.

In April Grace Wilson finished her stint as acting matron-in-chief in London and returned to Abbeville, and on 24 April Jean returned to No. 5 SH at Dieppe to resume her role as matron. However, for a short while the hospital was not the quiet place it had been. Following the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on 3 March with Russia, Germany had been able to transfer hundreds of thousands of men to the Western Front, pouring them into renewed offensives. The thousands of Allied casualties that resulted flowed from dressing stations on the battlefield to casualty clearing stations and on to general and stationary hospitals. At one point Jean and her two-dozen nurses were caring for some 1,800 patients, many of whom were badly wounded.

Return TO ENGLAND

Jean’s second stint at No. 5 SH lasted six months. On 3 October 1918 she reported to the principal matron in Boulogne and soon found herself sailing back over the Channel to England. She had been assigned once again to No. 2 AAH in Southall, Middlesex, and after passing through London arrived for duty on 5 October.

Jean did not stay long at Southall. On 18 October she left for No. 1 Group Clearing Hospital at Sutton Veny in Wiltshire to assist with a virulent outbreak of influenza. Before long, Jean contracted influenza herself and on 30 October died of bronchial pneumonia.

Jean was buried on 3 November with full military honours in the St. John the Evangelist Churchyard at Sutton Veny, her coffin draped with an Australian flag and carried on a gun carriage to the cemetery, accompanied by a firing party and a band from the 1st Australian Training Battalion. Six captains of the AIF acted as pall bearers. Her funeral was attended by 40 nursing staff, 30 officers and over 300 NCOs.

A description of the funeral was sent by Lieutenant A. Carver, stationed at Heytesbury, Wiltshire, to his parents in Goulburn, New South Wales, and published in the Sydney Morning Herald on 30 December 1918, as follows:

Last week the matron of the hospital at Sutton Veney [sic] – a camp a couple of miles from here – died of this influenza that’s getting about. We arranged to supply the gun carriage and horses to bear the coffin from the R.B.A.A. [Reserve Brigade Australian Artillery]. The funeral took place this afternoon. We had three officers driving and two cadets as brakesmen on the limber. I happened to be one of them. We moved off from Sutton Veney at the slow march – a terrible thing for horses to keep up – and we did the mile to the church in just under an hour. The two brakesmen walked behind the gun carriage, and walking alongside me was Captain Jacka, the Australian V.C. and M.C. and bar. The road was lined with thousands of Australians, and it made the funeral ceremony even more impressive to see the way every man came up to the salute as the coffin passed – even little kiddies about 6 years old, seeing all the soldiers doing it, solemnly did the same. About 100 officers and 200 men attended, besides many others who came along, apart from the actual column at the slow march. I’m glad I had the privilege of going – it was most impressive.

In memory of Jean.

SOURCES

- Ancestry.

- Australian War Memorial, AWM41 946 – [Nurses’ Narratives] Staff Nurse Leila Brown Accession Number AWM2021.219.9.

- Australian War Memorial, AWM41 975 – [Nurses’ Narratives] Principal Matron Ellen Julia Gould. Accession no. AWM2021.219.35.

- Australian War Memorial, AWM41 988 – [Nurses’ Narratives] Matron A. Kellett. Accession Number AWM2021.219.47.

- Australian War Memorial, AWM41 1053 – [Nurses’ Narratives] Sister E. J. Tucker. Accession Number AWM2020.8.1291.

- Australian War Memorial, AWM41 1057 – [Nurses’ Narratives] Sister B. E. Williams. Accession Number AWM2021.219.116.

- Australian War Memorial, AWM41 1074 – [Official History, 1914–18 War: Records of Arthur G. Butler:] AANS [Australian Army Nursing Service] General – Brief history of the AANS from 1903. Accession Number AWM2021.219.133.

- Australian War Memorial, Unit Diaries, AWM4 Subclass 26/67 – No. 3 Australian General Hospital, AWM4 26/67/7 – September 1917.

- Australian War Memorial, Unit Diaries, AWM4 Subclass 26/73 – No 2 Australian Auxiliary Hospital, Southall, AWM4 26/73/15 – October 1918.

- Australian War Memorial, Unit Diaries, AWM4 Subclass 26/97 – Australian Army Nursing Service in Egypt, AWM4 26/97/1 PART 1 – June 1916 – April 1918.

- Badcock, I. (25 September 2021), ‘William Gwillim WALKER Family & Vron Property,’ History over Dinner (website).

- Barrett, J. W. and Percival E. Deane, P. E. (1918), The Australian Army Medical Corps In Egypt, Project Gutenberg.

- Bassett, J. (1990), ‘Jean Nellie Miles Walker (1878–1918)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 12.

- Great War Forum, ‘HMHS Gascon during the Gallipoli Campaign, 1915 [plus some early history]’ (Heather Ford (‘Frev’), 8 May 2020).

- Harris, K, ‘New horizons: Australian nurses at work in World War I,’ Endeavour (2014, Vol. XXX No. X, 2014, pp. 1–11).

- Libraries Tasmania.

- The National Archives (UK), ‘Hospital Ships, Line of Communication Units, HMHS Gascon, 1915 Jan–1919 Dec’.

- National Archives of Australia.

- National Army Museum, ‘Salonika Campaign.’

- Rae, R. (2020), ‘Nursing in the 1918 Pandemic, Nellie Miles Walker Part 1,’ Australian College of Nursing (website).

- Scarlet Finders (website), ‘War Diary: Matron-In-Chief, British Expeditionary Force, France And Flanders.’

- Through These Lines (website), ‘Dieppe,’ ‘No. 5 Stationary Hospital,’ ‘Dieppe in Sister Elsie Tranter’s diary’ and ‘Villa Marguerite.’

- Tregarthen, G., Sea Transport of the A.I.F., Naval Transport Board (available through Australian National Maritime Museum website).

- Wren, E. (1935), Randwick to Hargicourt: History of the 3rd Battalion, A.I.F., Ronald G. McDonald.

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS AND GAZETTES

- Commonwealth of Australia Gazette (24 Apr 1909 [Issue No.24], p. 964), ‘Military Forces of the Commonwealth’.

- The Cornwall Chronicle (Launceston, 21 Jul 1875, p. 3), ‘Police Court’.

- The Critic (Hobart, 12 Jan 1917, p. 3), ‘Social News’.

- The Daily Post (Hobart, 12 Dec 1908, p. 5), ‘Hospital Board of Management’.

- The Daily Telegraph (Launceston, 18 Dec 1917, p. 4), ‘Personal’.

- The Examiner (Launceston, 26 Apr 1909, p. 6), ‘Military Appointments’.

- The Mercury (Hobart, 29 May 1866, p. 1), ‘Family Notices’.

- The Sydney Morning Herald (3 Jan 1917, p. 7), ‘Awarded Royal Red Cross’.

- The Sydney Morning Herald (25 Dec 1918, p. 6), ‘Death of Distinguished Nurse’.

- The Sydney Morning Herald (30 Dec 1918, p. eight), ‘Distinguished Nurse’s Funeral’.

- The Sydney Morning Herald (11 Jan 1919, p. 7), ‘The Late Matron Walker’.

- Upper Murray and Mitta Herald (Victoria, 11 Sep 1913, p. 2), ‘Advertising’.