AANS │ Matron │ Second World War │ Malaya │ 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station & 2/13th Australian General Hospital

FAMILY BACKGROUND

Irene Melville Drummond was born on 26 July 1905 in Ashfield, a suburb of Sydney. She was the oldest child of Katherine Melville (1879–1964), born in Toowong, Brisbane, and Cedric Drummond (1881–1956).

Cedric was born in Springsure in Queensland. As an infant he travelled to England with his family then returned to Australia in 1892, settling in Moonta, South Australia. In 1902 he moved to Port Adelaide and began working for the Adelaide Steamship Company. In 1903 he was fourth officer on the SS Allinga.

Cedric met Katherine Melville, and they were married on 10 August 1904 at St. Patrick’s Church in Sydney. The following year Irene was born.

In June 1906, Cedric lost his hand in a machinery accident while working as an engineer on the Bullara, trading on the Western Australian coast. Perhaps as a consequence of this dreadful blow, the family moved to Exeter, a suburb next to Semaphore in Adelaide, where Cedric’s parents lived. Here Irene’s sister Phyllis Drummond was born on 18 May 1907. Another sister, Ruth Alice Drummond, was born three years later, on 2 November 1910, followed by a brother, Nelson Noel Drummond, on 1 June 1911. Nelson was born at Mrs Stewart’s Nursing Home in Semaphore.

In 1913 Cedric left the Adelaide Steamship Company and became a partner in Clark & Drummond, a customs, shipping, insurance, commission and forwarding agency. He stayed there until at least 1917.

SCHOOL

By now Irene had started school. She attended the Dominican Convent in Semaphore, founded by the Dominican Sisters, an Irish Catholic order originating in 13th-century France. She earned her Qualifying Certificate in 1918.

Irene appears to have had a liking for music. In April 1916 she passed her Trinity College London Music Theory examination in the Preparatory Division, for which she was awarded a prize at the end of the year. In 1917 she passed in the Junior Division and was again awarded a prize. She also gained her University of Adelaide Grade V Certificate in Music Theory at the end of 1916.

In the late 1910s or early 1920s, the family moved to Broken Hill, where Cedric took up a position as local manager of the Vacuum Oil Company. Irene and her sisters continued their schooling at the Convent High School (also known as St. Joseph’s Convent High School), run by the Sisters of Mercy. At the end of 1921 Irene gained her Intermediate Certificate. In the same year Cedric was honorary secretary of the Quartette Club, a choral society, and later vice chairman, then secretary-treasurer.

NURSING

In 1924, having finished her schooling, Irene decided to go into nursing and began training at Miss Lawrence’s Private Hospital (also known as Wakefield Street Private Hospital, and subsequently Miss Rowe’s Private Hospital) in central Adelaide. She passed her Nurses’ Registration Board examination in general nursing in April 1927 and completed her training. She continued at Miss Rowe’s at least until September 1927.

After leaving Miss Rowe’s, Irene went to Queen’s Home in Rose Park (subsequently renamed Queen Victoria Maternity Hospital) to train in midwifery. In May 1929 she achieved a pass with credit in her examination and gained her certificate. She remained at Queen’s Home for a further 12 months as sister, then undertook private nursing.

In early 1931 Irene was appointed Charge Sister at Angaston District Hospital in South Australia. Over the next two-and-a-half years she often acted as matron in the absence of Matron Dixon.

Irene joined Broken Hill and District Hospital in October 1933 and took up duty as sister in charge of Ward 2 (medical ward). In July 1934 she took charge of Ward 1 (men’s surgical ward) and held that position until her departure in October 1940. In 1935 she was appointed assistant matron as well and at various times acted as matron.

In 1934 a nurse by the name of Vivian Bullwinkel began her training at Broken Hill. She would later serve under Irene in Malaya and in time would become the best-known nurse in Australia.

ENLISTMENT

Following the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939, thousands of Australians were called up for home service with the Militia, while others volunteered for overseas service with an expeditionary force, the Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF) – particularly after May 1940, when Germany invaded France and the Low Countries and threatened Britain. Thousands of nurses were among the volunteers.

Irene was one of them. On 23 July 1940 she filled out her attestation form for service with the 2nd AIF, had her medical and was appointed to the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS), 4th Military District (South Australia). While she awaited her call-up, she continued to discharge her duties at Broken Hill in the same conscientious, untiring and able manner that she had always shown and for which she had come to be loved by patients and staff alike.

The months passed by, and finally Irene received word from the army that she was to present to Woodside Army Camp, 25 kilometres east of Adelaide, on 15 October. Two days after celebrating the news with her colleagues at the Grand Hotel, Irene was treated to a farewell party. On 13 October the medical and nursing staff of the hospital transformed the new nurses’ sitting room into a bower of roses, larkspur and bloom. That evening, between 20 and 30 staff offered Irene their good wishes, and Matron Hunter presented her with a leather writing case. Later, Dr William Dorsch, on behalf of the medical staff, presented Irene with a travelling rug.

The following afternoon the hospital’s nurse trainees gathered to present their beloved assistant matron with a fountain pen, and that night Irene left Broken Hill by train for Adelaide. She would never return.

WOODSIDE

On 15 October Irene reported to the camp dressing station at Woodside. Two days later Matron Hunter resigned from Broken Hill and District Hospital, and Irene was contacted and asked whether she would consider returning as matron. She declined, stating that she felt that her duty was to remain with the AANS for active service with the 2nd AIF.

Also posted to Woodside at that time were AANS nurses Mavis Hannah and Millie Dorsch, both from Adelaide. Millie was the niece of that same Dr Dorsch who had presented Irene with a travelling rug. On 8 November Irene, Mavis and Millie were appointed to the 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station (CCS). So was Elaine Balfour Ogilvy, from a prominent Renmark family, who would join them at Woodside on 25 November. Irene and Mavis were appointed to the rank of sister – Irene the more senior – and Millie and Elaine to the rank of staff nurse. Irene, Millie and Elaine each signed their attestation form on 29 November, thus formalising their enlistment, while Mavis had signed hers in August.

All four nurses stayed at Woodside until 8 January 1941. The following day they were called up and commenced duty with the 2/4th CCS, which was being raised in Hobart under the command of Lt. Col. Thomas Hamilton and was set for deployment to Malaya. Another medical unit, the 2/10th Australian General Hospital (AGH), was being formed in Sydney at the same time and was also set for deployment to Malaya.

A week after joining their unit, Irene, Mavis, Millie and Elaine were granted pre-embarkation leave and on 23 January were guests at a morning tea given by the president and members of the Commercial Travellers’ Club in Adelaide. The four were among a group of 20 or so AANS nurses and physiotherapists being farewelled prior to their departure for overseas. Most were set for service in the Middle East.

On 30 January Irene, Mavis, Millie and Elaine entrained for Melbourne, where they met two more 2/4th CCS nurses, Staff Nurses Shirley Gardam and Wilhelmina ‘Mina’ Raymont. Shirley, from Launceston, and Mina, originally from Adelaide, had sailed from Tasmania on 25 January, presumably with the main elements of the unit. On 1 February all six entrained for Sydney.

THE QUEEN MARY

Two days later, the six nurses travelled to Darling Harbour and were taken by ferry to the Queen Mary, which was anchored off Bradley’s Point. In the process of boarding the famous ship were the approximately 5,750 troops of the 22nd Brigade, 8th Division, 2nd AIF, known as ‘Elbow Force.’ They were set to sail to Malaya following a British request for Australian reinforcements to join British and Indian troops in garrisoning the British colonial possession. Travelling with the soldiers were several medical units, principally the 2/10th AGH, the 2/4th CCS and the 2/9th Field Ambulance.

Once on board, after meeting their 43 peers from the 2/10th AGH, Irene and the other 2/4th CCS nurses proceeded to establish a dressing station on the sixteenth deck, where they would treat the troops’ minor injuries and ailments. More serious cases would be sent to the 2/10th AGH, which had set up an operating theatre and a ward.

In the early afternoon of 4 February, the Queen Mary pulled out of Sydney Harbour to the cheers of the troops and the roar of thousands of sightseers around the harbour. As the ship came level with the Heads the ship’s band struck up ‘Haere-ra,’ (‘A Māori Farewell’) and the troops sang ‘Now Is the Hour when We Must Say Goodbye’ again and again.

Outside the Heads the Queen Mary joined the Aquitania and the Dutch liner Nieuw Amsterdam, which were carrying, respectively, Australian and New Zealand troops to Bombay, from where they would transship for the Middle East. The three ships put out to sea escorted by the Australian cruiser Hobart. On 8 February the convoy was joined by the Mauretania, which had embarked from Melbourne and was also bound for Bombay.

After a stop in Fremantle, during which two more 2/4th CCS nurses – Staff Nurses Peggy Farmaner and Bessie Wilmott – boarded the Queen Mary, the convoy set out again, now under the escort of HMAS Canberra.

On 16 February, when the convoy was immediately south of Sunda Strait, the Queen Mary broke away from the convoy. Amid much cheering from the troops, it circled the other ships and then steamed off towards Singapore. On 18 February the nurses arrived at Sembawang Naval Base on the north coast of Singapore Island, just across Johor Strait from the Malay Peninsula. Opened in 1938, the base was meant to play a significant role in the British Empire’s strategic defences against external threats in East Asia – particularly from Japan.

The nurses disembarked and were taken to adjacent railway sidings. They gave their names and addresses, were issued with rations, and then boarded a train that took them across the Causeway spanning Johor Strait to the Malay Peninsula. The 2/10th AGH nurses alighted at Tampin and were driven to Malacca, one of the Straits Settlements territories. Early the next morning they arrived at the Malacca General Hospital, a wing of which would serve as the unit’s base for the next 11 months. The 2/4th CCS nurses, meanwhile, continued north with their male colleagues to the town of Kajang in Selangor state. Kajang lay 20 kilometres south of Kuala Lumpur, the capital of Selangor (and also of the larger political entity known as the Federated Malay States), and 40 kilometres north of Seremban, the capital of Negeri Sembilan state, one of the Federated Malay States. The unit established its hospital in the Kajang High School.

PORT DICKSON, MALAYA

However, the 2/4th CCS nurses did not remain long at Kajang. In order to take bed pressure off the 2/10th AGH, whose hospital would not be fully operational for some time, camp reception stations (CRSs), otherwise known as field hospitals, had been established at Seremban and at Port Dickson, 30 kilometres away on the coast. The CRSs would serve the men of the 22nd Brigade, whose three battalions, the 2/18th, 2/19th and 2/20th, were camped in the broader area. On 20 February Irene, Mavis, Elaine, Millie, Shirley, Peggy and Bessie were detached to the 2/9th Field Ambulance, whose commander was in charge of the CRSs, and, together with a number of their male colleagues, proceeded to Port Dickson from Kajang and reported for duty at the CRS established at the Malay Depot Gymnasium. They were joined by Mina on 25 February. At Kajang, meanwhile, the remaining staff of the 2/4th CCS began to establish a special venereal diseases hospital.

By the end of February the CRS at Port Dickson had 50 beds and took everything except acute surgical cases. The CRS at Seremban had 35 beds.

Soon after the nurses’ arrival at Port Dickson, Elaine Balfour-Ogilvy wrote home to her parents. She told them that she was stationed “somewhere in Malaya” and quartered with seven other staff nurses, all of whom were struggling with the Malayan language. The nurses had been supplied with Chinese cooks and “house boys” and were enjoying themselves as much as was possible under the circumstances. They found plenty to do and were very keen in their work and did not mind long hours and the many discomforts which invariably go with active service conditions.

After five months with the 2/9th Field Ambulance, Irene, Elaine and Mina returned to the 2/4th CCS at Kajang on 19 July. Millie and Shirley had returned on 7 May and Mavis on 4 June, while Bessie and Peggy would return to Kajang on 20 August, shortly before the redeployment of the 22nd Brigade to the east coast of the Malay Peninsula.

2/13TH AUSTRALIAN GENERAL HOSPITAL, SINGAPORE ISLAND

In early August a new medical unit was being raised in Melbourne for service in Malaya following a request from Col. Alfred P. Derham, Assistant Director of Medical Services (ADMS), 8th Division. Col. Derham felt that a second military hospital was urgently needed in view of intelligence reports that suggested the possibility of a Japanese invasion. The 2/13th AGH would consist of 225 staff, of whom 51 would be AANS nurses. Irene had been chosen as the unit’s matron and on 5 August was promoted to that rank.

On 15 September the 2/13th AGH arrived aboard Australian Hospital Ship Wanganella at Keppel Harbour on Singapore Island and berthed at Victoria Dock. The nurses disembarked and were met by Col. Wilfred Kent Hughes, the Deputy-Assistant Quarter Master General, who had organised buses to transport them to St. Patrick’s School, located 10 kilometres away in Katong on the south coast of the island. Here the unit would be billeted until its permanent base, an unfinished psychiatric hospital in Tampoi, in the south of the Malay Peninsula, could be made ready.

Ten nurses, however, had been detached upon arrival to the 2/10th AGH and did not even disembark with their colleagues. They later entrained for Malacca, somewhat dismayed at being so suddenly separated from their 2/13th AGH colleagues.

Meanwhile, the other 39 arrived at St. Patrick’s School. The requisitioned Roman Catholic boys’ school comprised several large, brick buildings and was set in extensive grounds. On its southern boundary the school was separated from Singapore Strait by barbed wire, landmines and notices that read ‘Danger – Keep Away.’ The nurses’ quarters were located in the south wing of the school and had views over the beach. They were comfortable, but the heat and humidity were oppressive.

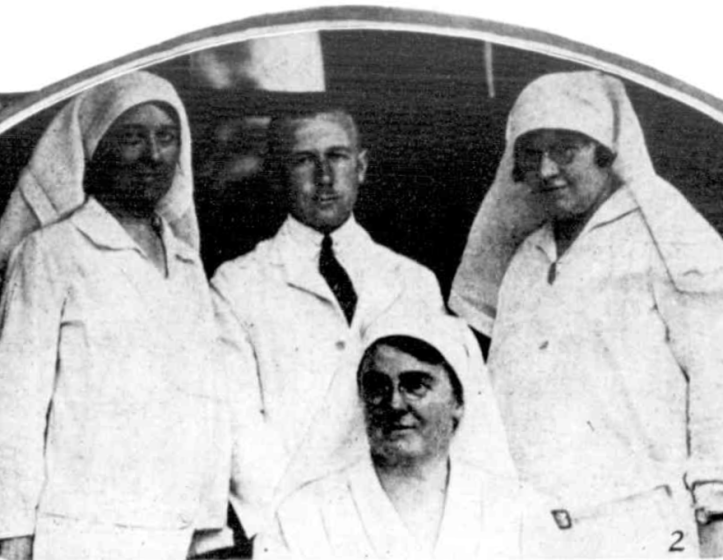

Irene – now Matron Drummond – arrived at St. Patrick’s on 19 September and met the nurses under her charge. Wearing her trademark spectacles and usually a smile, Irene very soon won the respect and goodwill of the newly arrived nursing staff.

Since there was no work for the 2/13th AGH nurses to do at this stage, most were rotated through detachments to the 2/10th AGH (as we have already seen) and the 2/4th CCS. Some were placed at the Singapore General Hospital, the main civilian hospital on the island. Thus dispersed, the nurses gained local experience in tropical nursing and were then able to instruct the nursing orderlies and stretcher bearers, most of whom already had some experience in bandaging and nursing, upon their return to St. Patrick’s.

When not on placement, the nurses attended lectures on tropical diseases, tropical nursing and other relevant topics, and were taken on field visits to the British Military Hospital (also known as Alexandra Hospital) to learn about malaria; to Tan Tock Seng Hospital, where clinics were conducted by Prof. Gordon Arthur Ransome and by a certain Dr. Wallace on Friday afternoons; and to Singapore General Hospital to see beriberi and typhoid patients.

There was plenty of time for leisure. In the afternoons, the nurses could play tennis or squash at the school, and sometimes at sunset they would walk down the road a little way to watch the 2/26th Infantry Battalion’s ‘changing of the guard’ ceremony. Provided they were back by 11.59 pm, the nurses were allowed out three nights a week and soon discovered that being (unmarried) women, officers and ‘British’ unlocked doors to Singapore society. Among other things, they were taken on sightseeing tours of Singapore Island, a “beautiful tropical jewel”; received invitations to tennis at lovely private homes and to dinner and dancing at the Airport Hotel; and were made honorary members of the Singapore Swimming Club, which fast became the most popular spot in Singapore for them. Two of Irene’s nurses, Phyllis Pugh and Margaret Selwood, were invited to government dinners at Raffles Hotel – very formal affairs, with glamourous people, magnificent décor, an abundance of tropical flowers, and music courtesy of the 2nd Argyll and Sutherland Highlander Regiment band.

After many weeks at St. Patrick’s School, the 2/13th AGH was finally ordered to proceed to the psychiatric hospital in Tampoi. In an extraordinary feat of logistics, 100 tons of equipment was moved in just three days, 21–23 November. Several of the unit’s nurses were already at the hospital, having been on detachment to the 2/4th CCS, which had until a short time before occupied the site. On 23 November Irene and the remaining nurses and other staff arrived.

Much work was needed to bring the hospital up to speed. Iron bars had to be removed from windows, and beds and equipment moved to make functional medical and surgical wards. Even so, the theatre nurses, Wilma Oram, Elizabeth Simons and Jenny Kerr, bemoaned the shortage of medical equipment available to them. To make matters worse, the hospital was not a particularly pleasant place to work. The wards were separated by long, covered concrete paths, and so bicycles were needed to get from one area to another. The nurses’ quarters, surrounded by a high brick wall, were far enough from the hospital to necessitate the use of a bus for transport.

WAR

Meanwhile, all the signs in the international arena pointed to war with Japan. At the end of November, shortly after the 2/13th AGH’s move to Tampoi, Commonwealth forces in Malaya were advanced to the second degree of readiness, which meant that leave was cancelled, and units had to be ready to move at a few hours’ notice to their areas of deployment. Then, on 4 December, the codeword ‘Raffles’ was given, indicating advancement to the first degree of readiness. War was coming.

Despite the official line and widespread belief that Commonwealth forces were sufficiently strong to stop any Japanese invasion, some of the 2/13th AGH officers thought otherwise. Maj. Bruce A. Hunt, for instance, shook the nurses out of their complacency one night by declaring unequivocally that the Japanese would invade from the north, advance down the peninsula unopposed, and trap the retreating British, Indian and Australian troops on Singapore Island.

Maj. Hunt was proved correct. Soon after midnight on 8 December, a force of some 5,000 troops of the Imperial Japanese Army launched an amphibious assault at Kota Bharu on the Malay Peninsula’s northern coast. They met little meaningful resistance. Four hours later, 17 Japanese bombers attacked Singapore Island. Having heard the bombs in the distance, some of the nurses at Tampoi decided that it must be a practice raid. Then they saw tracer bullets followed by ack-ack guns firing skyward at Japanese planes overhead. The realisation struck that they were at war with Japan.

From their beachhead at Kota Bharu, the well-trained, combat-ready Japanese forces, backed by mechanized units and substantial sea and air power, began to press southwards, forcing severely outgunned British and Indian troops to retreat before them. Within six days, two more Japanese forces had crossed into northern Malaya from Thailand.

On 12 December the unit received a memo from Lt. Col. J. G. Glyn White, Deputy ADMS 8th Division, ordering the hospital to expand from 600 to 1,200 beds. The memo also ordered that Red Cross brassards from then on be worn by all ranks on the left arm. Two new wards were opened on 15 December, and 15 nurses returned from detachment to the 2/10th AGH to staff them. A total of 643 beds were now available for occupancy. Irene made a point of visiting each ward in rotation to enjoy a tea break with her nurses.

LETTER HOME

Two days later, on 17 December, Irene wrote home to her sisters, Phyllis and Ruth. “Our hospital grows bigger daily and a tremendous lot of work has been done during the last ten days,” she told them. “We are in the throes of a thunder storm at present and my tent is not very water proof though it has the advantage of being cool and I get a breeze. I really don’t mind if the rain continues as it gives us a quiet night from air raid alarms as visibility is bad with the heavy clouds about.”

Irene thanked her sisters for sending a parcel of books. She complained about blackouts, calling them the “bane of my existence.” And she noted how difficult it was to write on blue airmail paper by the light of a hurricane lamp at night. She finished her letter with a joke. “What did the brassiere say to the top hat? You go on ahead & I’ll give the other two suckers a lift.”

Meanwhile, the Japanese advance showed no signs of slowing, and Irene and her nurses quickly became used to interrupted sleep, blackouts, gas drills with respirators and tin hats, and air-raid warnings. Some of the nurses were formed into a signals squad, whose job it was to ring a large brass bell upon receiving the message ‘Air Raid Red’ from the Army Signals Corps, whereupon the nurses and their amahs (housemaids) would head for the cover of the jungle.

Christmas came as a welcome distraction. The wards were decorated, and the Red Cross and Salvation Army were prevailed upon to boost the patients’ rations for the festive event. The officers helped to carve up the poultry and ham and helped the nurses to serve the bed patients. They also made the nurses sit down with the up patients and waited on them. In return the nurses arranged a party in their mess for the officers and on Boxing Day a larger party for the troops. Finally, the Sultan of Johor invited Irene, Col. Douglas C. Pigdon, commanding officer of the 2/13th AGH, and the officers and nurses who could be spared to a festive dinner at his palace.

EVACUATION TO SINGAPORE

Events sped up after Christmas. With Japanese progress southwards continuing unabated, it became clear that the 2/10th AGH at Malacca would have to evacuate to Singapore Island. On 29 December, 20 nurses were detached from Malacca to the 2/13th AGH and arrived the next day. On 5 January 1942, 16 more nurses and around 40 other staff were detached to the 2/13th AGH. Scores of patients had also been moved south from Malacca to Tampoi.

On 14 January Australian 8th Division troops entered combat for the first time. They scored a tactical victory against a Japanese force near the town of Gemas, in northern Johor state, but the following day a much bloodier battle was fought. Soon, convoys of Australian casualties were being sent via the 2/4th CCS, by now based at Mengkibol rubber plantation near Kluang, to the 2/13th AGH, which had 1,165 beds ready and had worked hard to prepare operating theatres to receive the anticipated casualties.

On the evening of 16 January, the war hit the unit hard. Australian casualties on stretchers with tickets pinned to them showing the most urgent injuries were delivered in rapid succession from transports of all types. The admission room quickly established identity, rank and injury, then stretcher bearers ran the casualty to either a ward or the operating theatre. Irene had her staff fine-tuned, and expert attention was provided at all times.

By now the 2/10th AGH had relocated to Oldham Hall and Manor House on Singapore Island, and before long the 2/13th AGH itself was compelled to follow its sister unit to the island. On 21 January a decision was made to return to St. Patrick’s School, and a handful of nurses and orderlies were sent there to clean and prepare it for the unit’s arrival. Abandoned bungalows adjoining the school were cleaned in preparation for their use as staff quarters.

The relocation took place over the weekend of 24–25 January. The final convoy, carrying medical patients, arrived late on Sunday night. Irene had ensured that beds had been made, pyjamas and towels placed at the ready, cold drinks and sandwiches prepared, and teapots got ready. By midnight all patients were safely bedded down. The move had been a startling success.

On 28 January the 2/4th CCS followed the other two medical units to Singapore Island, relocating to Bukit Panjang English School. Then, on the night of 30 January, the final Commonwealth troops crossed the Causeway from the Malay Peninsula to Singapore Island. The next morning it was blown in two places.

Irene and her colleagues were now working under considerable pressure. Their shifts were 12 hours long, and the theatre, blood bank and x-ray nurses worked even longer. Irene herself was working 16-hour days. And when the nurses did eventually finish their shifts, the constant air-raids, bombings and regular artillery barrages made sleep difficult.

On the night of 31 January, a bomb crashed into a corner of St. Patrick’s School during an air raid and wrecked the ceiling of a crowded ward. At the time of the bombing, a correspondent from the Australian Women’s Weekly, Harry Keys, happened to be visiting the 2/13th AGH. He later reported that when the rescue squad rushed up three flights of stairs, they found a night-duty nurse with a duster in her hand calmly clearing rubbish off the beds and generally setting the ward to rights. She had already been around among her patients seeing that they were all right and had calmed down those woken by the explosion. Miraculously none had been injured, although one had a small glass splinter in his shoulder. He noted how proud Irene was of the manner in which the nurse on duty had carried on.

Harry Keys also wrote of a soldier who had been very recently wounded by a Japanese shell. He was on a stretcher being carried from an ambulance to the ward. Although his knee had been splintered, he lay quietly on the stretcher with his arm crooked under his head. When he saw Irene, he raised himself and shouted “Hullo, Sister.” Irene waved to him as bearers took him into the theatre.

IRENE’S FINAL LETTERS

It was around this time that Irene sent her last letter to friends in Adelaide. “We are working 16 hours a day,” she wrote, as reported in the Adelaide News, “so there’s little time to worry about our personal welfare.” She also noted that “So far the Japanese have respected the Red Cross, both in Singapore and Johor.” The newspaper reported that her letters were full of praise for Australian soldiers, for the cheerful, tireless nurses under her, and for Red Cross aid.

On 5 February Irene wrote to her sister Phyllis again. It was possibly her last letter home. “There is nothing to write about as usual,” she began, “except bombs and more bombs which is not a particularly cheerful subject.” She told Phyllis that she has not received a letter since 20 January. “The stopping of the air mail is a great blow to us here, as the only bright spot was the regularity of the mail … Thank you for sending the [Reader’s] Digests. I expect they will arrive in time & all reading matter is … useful to us here.”

Irene then referred to the unit’s return to St. Patrick’s School. “Our new hospital is taking shape well and I am beginning to think it works like one now. For a few days I was in despair that we would ever be straight but it is amazing how things gradually right themselves. I have [Elaine Balfour] Ogilvey [sic] and [Millie] Dorsch attached to my staff now. [Mavis] Hannah and co. are with the other A.G.H. They are both very good workers and I am glad to have them with me.” She then mentioned acquaintances who had become casualties of war. “A good many of the officers I knew at Port Dickson have been killed or are missing. The two Scotchmen who taught us to do an eightsome reel on the Queen Mary have been killed. Another lad […] who took us out to dinner a couple of times is missing but the Australians are wonderful at finding their way and it is hoped that he will turn up again […]”

The ending of Irene’s letter is poignant indeed. “Well I must close. I hope you are all well. My best to George and I sincerely hope the war is over before he has to go away. I can’t help feeling very thankful that Nelson is not here. Heaps of love to all, Irene.” George was Phyllis’s husband and Nelson was Irene’s brother. Both served in Australia.

THE FINAL DAYS OF SINGAPORE

Japanese troops reached the northern shore of Johor Strait soon after the Causeway was blown and began a ferocious artillery bombardment of the island. They crossed the strait on the night of 8 February and by the morning had established a beachhead on the northwestern corner of Singapore island, despite strong opposition from Australian troops. The heavy fighting produced many casualties, and convoys of ambulances arrived at St. Patrick’s carrying hundreds of wounded soldiers, mainly with gunshot and shrapnel wounds. The hospital was by now so overcrowded with wounded combatants that outbuildings and even tents were used as wards. Casualties lay closely packed on mattresses on floors or even outside on the lawns.

With Singapore’s fate all but certain, a decision was made to evacuate the nurses. Already in January, following reports of Japanese atrocities in Hong Kong, Col. Derham had asked Maj. Gen. H. Gordon Bennett, commanding officer of the 8th Division in Malaya, to evacuate the AANS nurses. Bennett had refused, citing the damaging effect on morale. Col. Derham then instructed his deputy Lt. Col. Glyn White to send as many nurses as he could with Australian casualties leaving Singapore.

On 10 February, six 2/10th AGH nurses embarked with 300 wounded on the makeshift hospital ship Wusueh. The converted riverboat, painted white with large red crosses on both sides, had already been used to evacuate wounded from Singapore to Java. Although buzzed by enemy aircraft, the boat was not attacked and safely reached Tanjung Priok, the port of Batavia (today’s Jakarta). The nurses transshipped and eventually made it safely home to Australia.

The following day, Col. Pigdon and Irene summoned the 2/13th AGH nurses into their mess and told them that they were all to be evacuated when ships were available. That afternoon, the entire staff was assembled when ambulances arrived to transport the departing nurses to Keppel Harbour. However, it turned out that now only 30 were to leave, and Irene read out their names. They were requested to go quietly with no good-byes. They were to pack just one small suitcase and take respirators and ‘iron rations’ with them. And they had no option of either staying with the patients or waiting until all of the staff could leave together. They had to go.

Years later Staff Nurse Phyllis Pugh wrote of how she had been dragged out of the shower by Staff Nurse Margaret Selwood and told to hurry, as they were leaving, and the ambulances were waiting. Only Irene saw them off. She cuddled Phyllis and Margaret in her arms and said “Good-luck kids.”

Along with a similar number of counterparts from the 2/10th AGH, the 30 nurses of the 2/13th AGH departed on the Empire Star very early in the morning of 12 February.

Now 65 AANS nurses remained in Singapore, of whom 26 belonged to the 2/13th AGH. Late in the afternoon of 12 February, they departed too. They were driven by ambulance to St. Andrew’s Cathedral in Singapore city, which had been turned into a kind of casualty clearing station by the 2/9th and 2/10th Field Ambulances. Here, during one of the heaviest bombing raids Singapore had yet suffered, the 2/13th AGH nurses joined their comrades from the 2/10th AGH and the 2/4th CCS.

THE VYNER BROOKE

When the siren sounded all clear, the 65 nurses proceeded to Keppel Harbour until the ambulances could go no further. The nurses got out and walked the remaining few hundred metres. There were fires burning everywhere and on the wharf women and children were running everywhere trying to get on boats. Dozens of cars had been dumped in the harbour, and from the water protruded the masts of sunken ships. While the nurses were waiting, two bombs fell not far away.

Eventually Irene and her 64 comrades were ferried out to the Vyner Brooke, a small coastal steamer and one-time pleasure craft of Sir Charles Vyner Brooke, lying at anchor in the harbour. On board there were as many as 200 people – women, children, old and infirm men. In the gathering darkness the ship slipped out of Keppel Harbour and, after straying into a minefield and spending time extricating itself, began its journey south. Behind the Vyner Brooke the city was burning, and a pall of thick, black smoke hung in the sky.

That night the Vyner Brooke made little progress and spent much of Friday hiding among the hundreds of small islands that line the passage between Singapore and Batavia. The two matrons, Irene and Dot Paschke of the 2/10th AGH, took the opportunity to work out a plan in the likely event of an attack by Japanese aircraft. Nurses were assigned to particular areas of the ship, where they would station themselves and whose passengers they would then assist to evacuate.

By the morning of Saturday 14 February, Capt. Borton was approaching the entrance to Bangka Strait. To the right lay Sumatra; to the left, Bangka Island. Suddenly, at around 11.00 am, a Japanese plane swooped over, then flew off again. At around 2.00 pm another plane approached before flying off. The captain, anticipating the imminent arrival of Japanese dive-bombers, sounded the ship’s siren and began a run through open water. When a squadron of dive-bombers appeared on the horizon, Borton commenced evasive manoeuvres.

As the bombers approached, the Vyner Brooke zigzagged wildly at full speed. The first wave of bombs missed the ship. The planes banked, lined up again, and came in for a second run. This time there was no escape. A bomb struck the forward deck, killing a gun crew. Another entered the ship’s funnel and exploded in the engine room. The Vyner Brooke lifted and rocked with a vast roar. A third bomb tore a hole in the side of the ship. The Vyner Brooke listed to starboard and began to sink. It was 15 kilometres from Bangka Island.

After the first explosion, the nurses hurried about the deck doing the work they had been assigned. They were carrying morphia and dressings in their pockets and administered first aid to wounded passengers, including their own colleagues, and helped them to the three remaining lifeboats. Irene entered one of them and, together with Matron Paschke, supervised its loading with wounded and elderly passengers. Several of their own nurses were taken aboard – those who could not swim – along with a number of crew members, including Lt. Bill Sedgeman, first officer of the Vyner Brooke. The lifeboat was stocked with first-aid supplies and lowered into the roiling sea. Then greatcoats and rugs were thrown down into it, and it began to drift away.

BANGKA ISLAND

Some hours later Irene’s lifeboat reached the shore of Bangka Island. The passengers got out and built a bonfire. It would be a beacon for other survivors. Soon they were joined by the survivors of another lifeboat, whose number included Irene’s former trainee at Broken Hill, Vivian Bullwinkel of the 2/13th AGH, and several badly injured nurses.

Saturday night passed, and on Sunday the survivors learned that Bangka Island had come under Japanese occupation. Lt. Sedgeman floated the idea of surrender to Japanese authorities as a viable option but agreed to wait until the following morning before deciding. The rest of the day passed uneventfully.

Early in the morning of Monday 16 February, another lifeboat and several life rafts came ashore carrying British soldiers and sailors. There were now more than 100 people on the beach. It was agreed unanimously to surrender to Japanese authorities, and a deputation left for the nearest large town, Muntok, to negotiate this. A short while later most of the group’s civilian women and children followed behind.

Around mid-morning the deputation returned with perhaps 20 Japanese soldiers. The soldiers separated the survivors into three groups: the officers and NCOs, the servicemen and male civilians, and the AANS nurses and at least one civilian woman. They took the first two groups in turn around a nearby headland and murdered them, bayoneting the first and machine-gunning the second.

The Japanese soldiers returned to the women and ordered them to line up on the beach with their faces to the sea, even those who were injured.

The women began to walk into the water, and the soldiers opened fire. Twenty-one nurses died, including Irene, along with the civilian women. Only Vivian Bullwinkel survived.

In memory of Irene.

SOURCES

- Ancestry.

- Arthurson, L., ‘The Story of the 13th Australian General Hospital, 8th Division AIF, Malaya,’ edited by Peter Winstanley (2009).

- Australian War Memorial, ‘The Last Letters of Matron Irene Melville Drummond,’ AWM2025.6.17.

- Australian War Memorial [Medical Stores – Supply], Medical Correspondence between Brig. C. H. Stringer, Headquarters Malaya Command, and Major J. G. White, Headquarters 8th Australian Division, Malaya, 1941, AWM54 483/9/11.

- Jeffrey, B. (1954), White Coolies, Angus & Robertson Publishers.

- National Archives of Australia.

- National Library of Australia, Oral History Program, ‘Mavis Hannah interviewed by Amy McGrath,’ interview conducted at Grove Hill House, Dedham, Colchester on 13 July 1981, transcript and audio.

- Shaw, I. W. (2010), On Radji Beach, Pan Macmillan Australia.

- Syer (née Trotter), F., ‘Nurses’ Story: Told by Sister Florence Syer,’ reproduced by Peter Winstanley on the website ‘Prisoners of War of the Japanese 1942–1945,’ from Dixon, J. and Goodwin, B. (2000, 2010), Medicos and Memories.

- Walker, A. S. (1962), Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 5 – Medical, Vol. II – Middle East and Far East, Part II, Chap. 23 – Malayan Campaign (pp. 492–522), Australian War Memorial.

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS

- The Advertiser (Adelaide, 2 Apr 1913, p. 2), ‘Advertising.’

- The Advertiser (Adelaide, 10 Apr 1937, p. 27), ‘Broken Hill News.’

- The Advertiser (Adelaide, 25 Jul 1940, p. 15), ‘Army Nurses Appointed.’

- The Advertiser (Adelaide, 21 Jan 1941, p. 13), ‘Morning Tea for Army Nurses.’

- The Advertiser (Adelaide, 28 Jun 1944, p. 5), ‘Nursing Sisters Presumed Dead.’

- The Advertiser (Adelaide, 3 May 1946, p. 10), ‘Out among the People.’

- The Australian Women’s Weekly (21 Feb 1942, p. 7), ‘A.I.F. Nurses Inspired Besieged Singapore.’

- Barrier Daily Truth (Broken Hill, 10 Oct 1949, p. 3), ‘High Tribute Paid to Heroic Nursing Sister.’

- Barrier Miner (Broken Hill, 23 Feb 1922, p. 1), ‘The Schools.’

- Barrier Miner (Broken Hill, 6 Jul 1929, p. eight), ‘Personal.’

- Barrier Miner (Broken Hill, 11 Oct 1940, p. 3), ‘Sister Drummond tor Overseas.’

- Barrier Miner (Broken Hill, 14 Oct 1940, p. 4), ‘Farewells to Sister Drummond.’

- Barrier Miner (Broken Hill, 18 Oct 1940, p. 1), ‘Matron Hunter Resigns.’

- Barrier Miner (Broken Hill, 26 February 1949, p. 4), ‘Drummond Memorial Park.’

- The Brisbane Courier (17 Sep 1904, p. 4), ‘Family Notices.’

- Daily Herald (Adelaide, 24 Aug 1915, p. 3), ‘Crazy with Drink.’

- The Express and Telegraph (Adelaide, 14 Jun 1906, p.2), ‘Accident to a Ship’s Officer.’

- The Kadina and Wallaroo Times (2 May 1934, p. 3), ‘Late Dr. Drummond.’

- Leader (Angaston, 26 Mar 1931, p. 2), ‘Angaston District Hospital.’

- Leader (Angaston, 6 Aug 1931, p. 1), ‘Voluntary Help Meant Big Thing to Angaston District Hospital in Past Year.’

- Murray Pioneer and Australian River Record (Renmark, 13 Mar 1941, p. 12), ‘Nurse Balfour-Ogilvy “Somewhere in Malaya.”’

- News (Adelaide, 17 Feb 1942, p. 5), ‘Matron’s Letter from Singapore.’

- News (Adelaide, 11 Mar 1942, p. 5), ‘A.I.F. Matron on Way Home.’

- News (Adelaide, 12 Aug 1946, p. 5), ‘Old School’s Tribute to A.I.F. Matron.’

- The Register News-Pictorial (Adelaide, 3 Dec 1929, p. 22), ‘People in the Country.’

- Southern Cross (Adelaide, 12 Oct 1945, p. 9), ‘Matron Irene Drummond.’