QAIMNSR │ Sister │ Second World War │ France, Egypt & Sudan

FAMILY BACKGROUND

Hilary Glazebrook was born in Newark-on-Trent, Nottinghamshire, England on 27 June 1909. She was the eldest of three daughters born to Margaret Cook Melville (1876–1957), born in Kirkcaldy, Scotland, and Robert Herbert Glazebrook (1880–1947). Robert was born at Newark-on-Trent and was the son of Samuel Glazebrook, a well-known nurseryman and seed merchant in Newark.

Margaret and Robert were married in Newark in 1908, and the following year Hilary was born. A second daughter, Mary, followed in 1910.

Sometime after Mary’s birth the family decided to migrate to Western Australia. Robert arrived first, departing London aboard the Australind on 29 July 1913 and arriving in Fremantle on 6 September. He made his way to Mount Barker in Western Australia’s Great Southern region and found work as a seedsman at the Mount Barker Estate. On 12 June 1914 Margaret and the girls arrived at Fremantle on the Armadale and joined Robert, either at Mount Barker or at Albany, 50 kilometres further south – where, in 1915, a third daughter, Joan Millicent, was born.

In Albany Robert was employed by Mr Ernest McKenzie, who since February 1914 had owned C. H. Neumann & Co., general merchants, on Stirling Terrace. By July 1915 McKenzie had opened an arm of the business known as The Seed Warehouse.

The year 1916 was a significant one for Robert. In March, evidently no longer in the employ of Ernest McKenzie, he began to advertise his own nursery on York Street – “Seeds, Plants, Fruit Trees. Flower, Farm and Garden Seeds. Mixtures of Grasses and Clovers for all purposes and soils” – and in July he enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF). He was sent as a private to No. 80 Depot at Blackboy Hill Army Camp in Mundaring, outside Perth, but was discharged on 22 September as permanently unfit due to a cyst in his neck and heart hypertrophy.

A fourth, unnamed daughter was born to Margaret and Robert in 1920 but died at or soon after birth.

By 1921 Robert had moved his nursery to Vancouver Street. He moved again in early 1925 to Middleton Road, where he developed his business on a large scale and where he continued to trade until shortly before his death in 1947.

EARLY LIFE

We do not know where Hilary went to primary school, but we do know that she and Mary were pupils at the Sunday School at the Scots Church on York Street. At the annual distribution of prizes, held on 11 April 1918, Hilary was awarded first prize in her class.

After finishing at primary school, Hilary attended Albany District High School. In December 1922 she was one of the seven good fairies in a school production of the three-act operetta ‘Briar Rose or the Sleeping Beauty’ held at the Empire Theatre. Perhaps she liked performing; two months earlier, in October, she had appeared as part of the baby pony ballet in a pantomime version of ‘Robinson Crusoe’ staged at the Empire Theatre.

In October 1924 Hilary passed examinations in English, shorthand and arithmetic at the Albany Continuation School and gained her Pass-out Certificate in December.

As a young woman Hilary moved to Perth and was employed for a time in the office of St. George’s Anglican Cathedral. Reportedly, one of her personal treasures was an autographed portrait photograph of Archbishop Charles Leaver Riley, the first Anglican archbishop of Perth.

NURSING

In 1928 Hilary began to train as a nurse at the Perth Public Hospital. She had finished by the end of 1930 and on 5 June 1931 obtained her registration. She was then appointed to a position at the Gnowangerup Hospital, around 120 kilometres north of Albany. Dr. Hanrahan from the hospital was a resident of Albany and may have helped Hilary to secure the appointment.

In March 1932 Hilary was appointed to the nursing staff of the Wiluna Public Hospital, more than 1,000 kilometres north of Albany in the vast Western Australian outback. She resigned two years later, on 11 April 1934, and by July that year was nursing in Perth.

Hilary then travelled to northern Western Australia to nurse in Broome – a town as far north of Wiluna as Wiluna was of Albany. In March 1935 she relieved for a week in Derby, 200 kilometres north of Broome. She arrived by boat and returned by plane.

After returning to Perth in May 1935, Hilary ventured north once again when she was appointed to the staff of the Carnarvon Hospital, 800 kilometres from Perth. She finished her stint in mid-December and returned to Perth on the Koolinda. Meanwhile, in September, Hilary’s sister Joan had begun nurses’ training at Perth Public Hospital.

On 28 December Hilary returned to Albany with Mrs. Mafeking Turpin (née Crofts), known as Mafe or Maffie, a friend of Hilary’s. Maffie was driving to Albany her young son Peter to spend a holiday with her brother Joshua Reidy-Crofts, who ran a hotel in Albany, and his wife.

LONDON

By then Hilary must already have been planning the trip to England that would change the trajectory of her life. She was due to depart in March and in the meantime took up a short-term appointment at the Albany Government Hospital.

On 22 March 1936 Hilary caught the night train from Albany to Fremantle and the following day attended an afternoon tea party at the Esplanade Hotel in Perth. The party was given by Mrs. Walter Seale in honour of her daughter, Grace Seale, who was due to leave for London three days later. Hilary was sailing with her.

At around 1.40 pm on 26 March Hilary and Grace departed from Fremantle on the P&O liner Bendigo, the ship’s final voyage before being sold for scrap in Barrow. They arrived in Plymouth, Devon just over a month later, and here Hilary disembarked to visit friends in Sidmouth. Following her visit she intended travelling north to Scotland. In the meantime, Grace continued to London, arriving on 26 April.

In due course Hilary herself arrived in London and, despite the fact that she did not become registered for nursing in the United Kingdom and Ireland until 26 May 1939, began to work for the Hourly Nursing Service (HNS). The HNS was a private nursing business established around 1932 or 1933 by a New Zealand–trained nurse, Marie Dorothea Muir, whose nurses could be booked for an hour – or longer. On 15 April 1937 the Perth Daily News reported that Hilary had found “jobs plentiful, and her services much in demand while in London. One job took her on a trip to France.”

At the time of the report in the Daily News, Hilary was sharing a flat on Leicester Square with fellow Perth Public Hospital trainees Pearl Martin, Mary Stewart and Alexina Hawkins, who was known as Lalla or Lal.

THE CORONATION OF KING GEORGE VI

When Edward VIII abdicated on 10 December 1936, with effect from the following day, his brother Albert ascended the throne as George VI. Albert’s wife, Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, became Queen Elizabeth. Edward’s coronation had been planned for 12 May 1937; it was decided to keep that date for the coronation of George and Elizabeth.

On the day of the coronation a festive atmosphere pervaded central London. Thousands of people lined the streets to see the royal procession. Hilary was one of them. It was a thrilling experience, and the following day she wrote to her mother to tell her about it. On 7 June the Perth Daily News printed extracts of Hilary’s letter.

Yesterday [12 May] was the Coronation, and what a day! It was absolutely marvellous. I got a seat from Australia House, and as I waited for a returned seat, got a wonderful view of everything. It was one of the best seats along the route in the Parliament-square stand, looking up the Broad Sanctuary to the annexe of the Abbey I saw the procession both going to the Abbey and coming back, and was very close to it all.

I was in my seat by 6 a.m. Everyone got a form with their tickets, giving full instructions as to the best way to get there. All along the six miles of the route there were tier upon tier of stands. I paid 22s 6d for my seat, which was a covered one. [An] uncovered one was 15s, but wasn’t I glad I took the covered one, as it poured with rain in the afternoon.

[…]

We saw all the guests arriving at the Abbey, and the marvellous processions of soldiers, all in their various colored uniforms. The Royal Family arrived in glass coaches, accompanied by mounted guards. Queen Mary’s procession was wonderful. We also saw all the Dominion Prime Ministers, accompanied by detachments of their own mounted men.

The Australians got a wonderful reception from the crowd, but the most colorful of the Dominions’ detachments was the Canadian North-West Mounted in their scarlet coats. The King, and Queen came last, in their gold coach. The color and glitter were marvellous.

The Dukes of Gloucester and Kent rode behind, with naval and military commanders and Indian maharajahs.

We had the whole service in the Abbey relayed to the stand, and the most impressive moment came when the King was crowned. The bells pealed, guns fired, and the crowd all sang the National Anthem with the Abbey choir.

At 8 o’clock we started out to see the illuminations. We went down Piccadilly, along Regent-street and Oxford-street. What a crowd! They were all mad, singing and dancing. Just like New Year’s Eve.

The decorations, I thought, were rather poor, and Bond-street looked just like an Eastern port on washday, but Selfridge’s, as usual, was a sight worth seeing. Every notable building was floodlit, and the whole of London went mad. Every street in the West End was closed to traffic, and as the bus strike was on, the tubes were packed. It was rather funny, but no one missed the buses, as the traffic arrangements were so good, and there was no scrambling in regard to getting to the different stands.

TRAVELS ABROAD

Earlier in 1937 Maffie Turpin and Peter had arrived in England after spending time in Malaya en route. After her arrival, Maffie bought a brand-new deluxe model Baby Austin, with all the latest gadgets, for £128, and in the middle of the year she and Hilary toured through France, Belgium, Germany, Austria and Italy, stopping and starting as fancy took them. During this time Peter remained in England at boarding school.

Later in 1937, while still working for the Hourly Nursing Service, Hilary was engaged to accompany a patient to the United States. On 9 October she departed Southampton aboard the Normandie, at the time the largest and fastest passenger liner in the world, and, travelling in cabin class, arrived in New York four or five days later. After a week she departed New York on the Queen Mary – the second-largest passenger liner – and arrived at Southampton on 25 October having sailed in tourist class. Curiously, Hilary’s address is stated as 6 Pembridge Place, London W2 in the Normandie’s manifest and as 18 Pembridge Place, London W2 in the Queen Mary’s. Pembridge Place was where the Hourly Nursing Service was located.

In 1938 Lal Hawkins’s sister Ethelwyn Hawkins, known as Wyn, arrived in London. Wyn was another graduate of Perth Public Hospital and may have lived with Hilary and some or all of the other Western Australian nurses for a while. By September 1938 Hilary had apparently moved to flat at 78 Kensington Park Road in Notting Hill.

“PEACE FOR OUR TIME”

On 29 September 1938 British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain signed the Munich Agreement ceding the Sudetenland to Germany. He returned to London the following day and declared from 10 Downing Street that he had achieved “peace with honour. I believe it is peace for our time.” The news was met with jubilation. Londoners had been preparing for war and were greatly relieved that the threat had seemingly passed. On 1 October Hilary wrote to tell her parents, and excerpts of her letter were printed in the Albany Advertiser on 20 October.

What a time we have had this last week, but now, thank goodness, everything is settled. Everyone really thought that there was to be a war, and on Wednesday morning it looked as though nothing could stop it.

I got back from Scotland and went down to Bournemouth to stay with the last patient I had, and so was out of London while all the preparations were going on, but I had to ring through to see what was doing about the nurses, and was told we were already being drafted into units for service. London looks as though it had been dug up all round. Kensington Gardens was a mass of trenches for air-raid shelters. Hyde Park was being mapped out with tents for soldiers. Parts of the underground railways had ceased and were also shelters. Sandbags were placed everywhere and when it came to large guns on the river bridges, it really looked as though the war was a fact.

The school children had, on the Tuesday [27 September], already been evacuated to the country from various school centres, and of course everyone had gasmasks issued to them. We have all got ours and so far we have to keep them. In Bournemouth, and also everywhere in England, trenches had been dug. The girls told me that on Tuesday and Wednesday, everyone was walking round with very long faces, and the shopkeepers were sold out of various tinned goods, candles, etc.

I came back to London on Friday evening [30 September], and got a taxi at Waterloo, but coming back we were in the biggest traffic jam for a long time, and the driver told me the Premier [Chamberlain] was due back in Downing Street any time. As we came round the Birdcage Walk and in the square in front of Buckingham Palace, the taxi had to stop and wait. There were thousands of people at the Palace, as Mr. and Mrs. Chamberlain had been to see the King and Queen, and they had been out on the front balcony. The Premier was just about to leave the Palace for Downing Street when my taxi was passing and their car passed alongside the taxi. Everyone was cheering madly, and it was a great thrill to be in the thick of it. The Premier is the man of the moment, but of course he will come in for a lot of criticism with many people now everything is over. But in any case peace is assured in Europe for the next 50 years.

I’ve never felt that war was so imminent before, and it certainly was an excitement to be in England at the moment. My stay here has certainly been in historic times, the Coronation and abdication, and now this, but I’m very glad that the war scare is over.

WAR

Of course, the war scare was very much not over. In August 1939, presumably while still with the Hourly Nursing Service, Hilary travelled to Switzerland with (or to meet) a client. While she was there, war broke out. On 1 September Germany had invaded Poland, and two days later, Great Britain and France had declared war on Germany.

Hilary returned to London and joined the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service Reserve (QAIMNSR). She was appointed to the rank of sister on 20 November and awaited mobilisation.

Meanwhile, immediately upon the declaration of war, Pearl Martin and Lal and Wyn Hawkins had joined the River Emergency Services under the Port of London Authority. They served on the small ambulance ship Royal Princess in the Tilbury area of the Thames.

Hilary was mobilised in early 1940. In April she departed London for service in the Near East with a group of Australian QAIMNSR nurses that included Sister Norah Henshaw Jackson, Sister Elsie Hughes and Sister Effie Williams of Adelaide, and Sister Margaret Byrne and Sister Zeryl Joseph of Sydney. Theirs was an advance party; a larger group that included Wyn Hawkins, who had joined the QAIMNSR in early 1940, was to follow. Altogether the contingent would number around 50 nurse. At that time there were already 15 Australian QAIMNSR nurses serving in Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) hospitals in the Near East, as well as 43 in France, three in Malta, and three on hospital ships.

Around 28 April Hilary’s advance party crossed the Channel to Cherbourg in France and from there travelled by train to a locality rendered as “Le Marr” in The West Wyalong Advocate on 2 September 1940, possibly meaning Le Mans. In “Le Marr” the nurses stayed at a good hotel for two weeks, then went on to Marseilles for a week. From Marseilles they were to have embarked for the Near East, but by then German forces had invaded France, and the Mediterranean had become too dangerous to cross. It was decided to return the nurses to England. After travelling in trains guarded with anti-aircraft guns, they crossed the Channel in a convoy escorted by warships and fighter planes and arrived at Southampton five days after leaving Marseilles. It was now close to the end of May.

Meanwhile, Wyn Hawkins’s party – the main group – appears not to have reached Marseilles and possibly did not even cross the Channel in the first place. In May, Wyn was posted to Sierra Leone in West Africa, and it seems unlikely that she can have returned from Marseilles at the end of that month only to be sent off again immediately. Hilary for her part was not sent abroad again until September, when she returned to the Near East. This time, however, she sailed from England to Cairo via the Cape.

TO EGYPT

From Cairo Hilary travelled to Alexandria and by January 1941 had been posted to what was referred to in the Perth Listening Post (on 15 January 1941) as the “2/5 General Hospital.” Presumably this was not the 2/5th Australian General Hospital (AGH) – which, aside from being Australian, was based at the time in Rehovot in Mandatory Palestine – and not No. 5 British General Hospital (BGH), which was not posted to Alexandria. There were at least two RAMC units which were based in Alexandria to which she may have been attached, No. 8 BGH at a former Italian school in the east of the city, and No. 64 BGH at Victoria College.

Regardless of which unit she was with, Hilary would have been treating British and Commonwealth casualties of the fighting in the Western Desert. In September 1940 several divisions of Marshal Rodolfo Graziani’s Italian 10th Army had invaded Egypt from Cyrenaica, eastern Libya. They pushed as far east as Sidi Barrani in western Egypt being held up by British and Commonwealth forces. In December, the Allies launched a counteroffensive, known as Operation Compass, and by February 1941 the Italians had been routed.

JOURNEY TO SUDAN

In March 1941 Hilary was transferred to an RAMC general hospital in Sudan. During her journey south she began a letter to her parents and continued it after her arrival. Excerpts from her letter were printed in the West Australian on 10 May 1941.

Another girl (Sarah Davidson) and I were going on leave to Palestine in a fortnight’s time, but on Tuesday a ring came through to the ward saying Sarah and I were to go off duty immediately and pack to leave for the Sudan next day – just the two of us going. We had a mad rush into town buying soaps, cosmetics, etc., as these things are hard to get. We both have an enormous lot of baggage – camp kit, field equipment and trunks, and had to buy another suitcase each. We left Alexandria on the noon train, arriving at Cairo in the afternoon with a five days’ journey before us. We flew around Cairo that afternoon seeing people we knew and found to our great surprise two other girls we knew were also going.

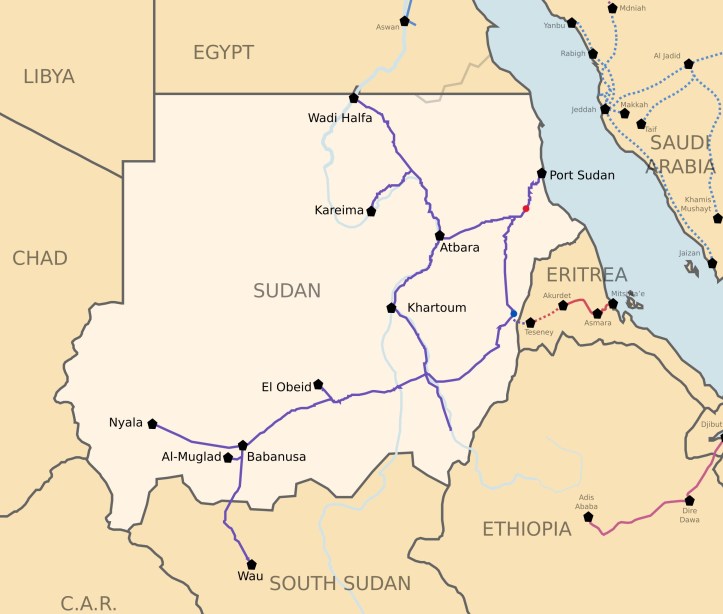

Here we are now sailing down the Nile on a steamboat. It is an experience one would not ordinarily enjoy. We left Cairo by train at night and got to El Shellal [south of Aswan] next day at midday and boarded the steamer, which is what one would imagine a Mississippi show boat to be like – paddle steamer type. The train journey was down the valley of the Nile and there was a certain amount of greenery, with palm trees and maize crops along the banks, but now we are passing through rocky hills and desert. It is pleasantly warm so far and we have changed into light frocks. Last night it was beautiful with a full moon on the river. There are not many travelling just now – we four women and some officers taking this steamboat journey for 48 hours to Wadi Halfa. From there we go on by train for 24 hours to Khartum [sic], then another 12 hours into the blue to our destination. This is an experience that American tourists pay hundreds of pounds to do in peacetime.

The rest of the journey here was very hot, but the Sudan trains are infinitely better than the Egyptian. On the train from Wadi Halfa I had dinner at night with the Governor of the Province, who invited the four of us to his home the next day. We got off at 2 a.m. and were not continuing until 6 p.m. that day, so we had a lovely day. He sent his car for us and we just made ourselves at home at his house. He sent us down to the Nile to bathe; we went a distance by car, then horsebacked to the river. We arrived at this place the next day, absolutely filthy and very hot. As we are in the hills it is very much cooler, but nevertheless hot.

As there was no accommodation in the barracks (there are 20 more nurses here), the four of us have a tent. The place rather reminds me of Wiluna, only there are very high hills all round us – rather a fine sight.

NO. 16 British GENERAL HOSPITAL, GEBEIT

We cannot be certain, but Hilary had possibly been posted to No. 16 BGH in Gebeit, a town in the hills of northeastern Sudan. No. 16 BGH’s commanding officer, Colonel Ernest Scott, a prolific diarist, wrote cryptically on 30 March that “a few sisters came w Lea in afternoon.” Of course, it could be anyone, but the location, the timeline and the size of the party all accord with Hilary’s story.

No. 16 BGH had relocated from Helmieh in Cairo to Gebeit in late January 1941 to support General Archibald Wavell’s campaign against the Italian and local forces of Prince Amedeo, Duke of Aosta, the commander in chief of military forces in Italian East Africa.

Italian East Africa, which comprised Ethiopia, Italian Somaliland and Eritrea, had come into being in 1935 following Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia, which sent Emperor Haile Selassie into exile. In August 1940, following Mussolini’s declaration of war on Britain two months prior, Italian forces captured British Somaliland. In response, General Wavell, British Commander-in-Chief Middle East, launched a three-pronged counteroffensive. In January 1941 British, Indian and other Commonwealth forces led by Lieutenant General William Platt entered Eritrea from Sudan. The capture of Fort Dologorodoc on 16 March during the decisive Battle of Keren marked the turning point in the campaign, and on 1 April Platt marched into the capital, Asmara, unopposed. By 10 April Massawa, Eritrea’s main Red Sea port, had been taken, and on 27 April the Massawa–Asmara railway was reopened.

Meanwhile, a second Allied force had advanced north from Kenya into Italian Somaliland, while a third force crossed from Aden and by the end of March had retaken British Somaliland. These three forces linked up and pushed into Ethiopia, entering the capital, Addis Ababa, on 6 April.

During the fighting, Gebeit had served as an important medical hub. Aside from No. 16 BGH, Nos. 10, 16, 30 and 53 Indian GHs, No. 14 Combined GH and the Indian Convalescent Depot were based in the town or in the broader area. Gebeit was on the main Port Sudan–Khartoum railway line, and a line also ran from Haiya (a junction town just south of Gebeit) to Kassala, near the Eritrean border. A branch line connected Kassala to Tessenai in western Eritrea, and from here 3,000 British and Commonwealth casualties of the Battle of Keren were evacuated by ambulance train to Gebeit for distribution among the hospitals. Two hundred and eighteen British and 160 Indian casualties arrived on the afternoon of 18 March, with another 130 British and 250 Indian casualties arriving the following day. At that point there were still an estimated 2,000 men awaiting transport in Keren.

Hilary wrote to her parents again in a letter dated 12 April, and excerpts were printed in the West Australian on 10 May 1941. Hilary wrote that she was now with a mobile unit and living under canvas.

I sleep on a camp bed and in fact have all my camp and field equipment out. It is remarkable how comfortable one can be. The only thing we all miss is a good meal, as we are on army rations of bully beef and biscuits. Of course, the bully beef is made into stew and we have tinned herrings in tomato sauce – I’ll never look them in the face again – and cheese.

The dust storms are rather like those at Wiluna and you can imagine what they are like in a tent. There is nowhere to go, of course, but the social life is very gay. We go to dances very frequently, also picnics, etc. Last week we went to a dance with the Air Force 16 miles away and next night to another mess a few miles away, and so on, so you see it is really not so bad. In Alexandria, of course, we had the beaches, which were marvellous and the night life of the town. We also had a marvellous sisters’ mess.

HOLIDAY IN ERITREA

Around June Hilary was granted leave and travelled to Eritrea. By then only pockets of Italian resistance remained in Italian East Africa, and none in Eritrea. Haile Selassie had returned to Addis Ababa on 5 May; and the Duke of Aosta had surrendered on 18 May following a final stand at Amba Alagi in the mountains of northern Ethiopia.

As usual, Hilary described her trip in a letter to her parents, and again excerpts were printed, this time in the Mount Barker and Denmark Record on 7 August.

Sorry I have not written for the last three weeks, but I have been on leave on one of the most interesting holidays I have ever had. As Sarah Davidson and I were the first due in this unit and were over-due for leave, we were asked if we would like to go to Asmara, and of course we jumped at it as we had heard good reports of the climate there. Also it was too far to go to Egypt, and besides it was very hot there.

We set off at night with the leave party, consisting of two other Sisters and two officers, also ten of the personnel of the unit. We had our own carriage hooked on to a goods train and travelled through the night, arriving at Tessenai in Eritrea the next morning. We had to take our own rations with us, as there was no way of getting food on the way. The country was awful, very desolate and looked absolutely unfit for cultivation of any kind. As we passed through two very bad dust-storms we were absolutely filthy by the time we arrived, but we didn’t care as the worst part of the journey was to come.

We had breakfast at the transit camp at Tessenai, which is just a camp of native huts called tukles. We left after breakfast with a convoy of trucks driven by South African Cape Corps – coloured lads who are marvellous drivers. The road to Agordat was an Italian-made one, the foundations of which were excellent, but after having so many vehicles driven over it for so long was rather like corrugated iron. We passed over ground which, three months before, was traversed and fought over by our troops on their way to the heights of Keren. Our coloured driver pointed out the interesting points, where the road was bombed – now repaired – and lots of places where fierce fighting took place. It is dreadful country and it must have been hell at times.

We arrived at Agordat at lunch time, looking blacker than ever, and just had time to catch the Diesel train which runs through Keren and on to Asmara. The gauge was very narrow and the train was rather like the Swiss mountain trains. The last part was the most interesting and the most comfortable, as, an hour after leaving Agordat, the railway started the climb into the mountains, making the coolness of the air a great blessing after the hot plains we had previously come through. We saw lots of baboons and gazelle as we started to climb and as it had rained a few hours previously the ground was awash and the previously-dry river beds were torrents. The mountains were very lovely and in the evening light, with the mists coming down, reminded me of the Highlands of Scotland. The little train just rushed round those mountains, and at times we looked down thousands of feet into the ravines.

We got to Keren at tea-time, and had enough time there to take a look round the place. We saw in the distance, before reaching Keren itself, the famous Fort Dologorodoc, which took so much time to take. It looks impregnable, and I am sure if our troops were defending it, it would never have been taken. Keren – the town – looked as if it had taken a terrible battering. The bombs had left their mark on practically every building, but it looked very quiet and peaceful in the afternoon sunlight. There was a lovely flame coloured tree rather like a poincianna [sic] just outside the station, which, with the added green-ness around gave the place a very attractive look after the flatness and barren-ness of the place we were in.

After another hour in the train and still climbing higher, for the first time since leaving England I was glad to don my overcoat, but not one of our party minded how cold it got after the heat we had had for months. It was dark before we got to Asmara and our first glimpse of the place was the street lights twinkling in the distance. Actually the place is situated on a high plateau, so we seemed to come on the lights suddenly.

Our first thought was a bath, and then food, but bath first as we were all terribly dirty. We were billeted with a C.C.S. [casualty clearing station] mess as the hotel was packed with officers, but we had a very comfortable room – a bath that ran hot water and a lavatory that flushed. That night we had thought of going straight to bed after dinner, but Sarah and I were dragged out to one of the night-clubs for an hour or so, and found much to our amazement, dozens of friends in the place – people we had travelled with in France, out of Egypt and coming down the Nile, so from there on we did not stop. Out every day and most of the night.

The only English women in the place were sisters from the other hospital where we were but who had moved up there. Their place was some distance out and then only came in occasionally. We went to see them one afternoon and I have never seen such a wonderful road and so hair-raising, out of Switzerland. The Italians certainly can make roads and this one went up and over and in and around the mountains for miles and miles, at every turn of the road giving the most lovely views, and looking down precipices. At some places it had been blown up by the Italians, but was now being repaired.

The shops were very poor as there was really nothing in them, but I found a few oddments.

The journey back was the worst, as the rains came down and it took us about four days to get to Khartoum where we were to stay for the finish of our fortnight. The humidity there was awful and we were in a perpetual state of dampness which after the cool dryness of Asmara, was awful. We took a trip out to Omdurman one afternoon and I bought a few things from the Street of the Silversmiths. Omdurman silver is one of the noted things in these parts, but very expensive of course, and is sold by weight. I bought ostrich feather fan – rather a silly thing perhaps in war time but I thought I may never be back this way again and it was an opportunity I did not want to miss, as they were so cheap. I would probably pay about two or three pounds in London for one which I got for about ten shillings.

Hilary remained in Sudan for six months. After June, there were few if any war wounded to treat, as the fighting had contracted to isolated holdouts in the mountains of northern Ethiopia, but there were plenty of medical cases. There were patients with parasitic diseases such as typhoid, dysentery, malaria, leishmaniasis (a sandfly-borne disease) and bilharzia (a waterborne disease). There were cases of tuberculosis and many cases of sexually transmitted diseases. The hospitals of Gebeit also looked after Italian, Ethiopian and Eritrean prisoners of war, many with scurvy (vitamin C deficiency) and diarrhoea cause by pellagra (niacin deficiency). Finally, there were accidental injuries and routine operations.

RETURN TO EGYPT

Around October Hilary returned to Egypt. She had been earmarked for service with an RAMC unit in Delhi, India but developments in the Western Desert delayed her embarkation.

Following the defeat of Italian forces in Cyrenaica in February 1941, Rommel’s Afrika Korps had landed at El Agheila in March. The Germans advanced rapidly through Cyrenaica and besieged Tobruk. At the time of Hilary’s return to Egypt, General Claude Auchinleck, who had replaced Wavell as British Commander-in-Chief Middle East, was planning Operation Crusader to relieve Tobruk and regain control of Cyrenaica. It would be launched on 18 November.

In the meantime, Hilary had been posted to an RAMC unit, most likely No. 1 BGH, in Kantara, a town straddling the Suez Canal between Ismailia and Port Said. The town was also the home of the 2/2nd AGH.

Hilary was a frequent visitor to the 2/2nd AGH, as several of the unit’s nurses had trained with her at the Perth Public Hospital. On the night of 18 November, she was returning from such a visit with Sarah Davidson, who had been posted to Kantara as well, in a car driven by an officer. While the vehicle was passing over a level crossing it was struck by a train, and Hilary sustained a fractured skull. She was either killed outright or died en route to hospital (likely either the 2/2ndAGH or No. 1 BGH). Sarah Davidson and presumably the officer were also taken to hospital.

Hilary was buried the following day at the British War Cemetery in Kantara (today the Kantara War Memorial Cemetery). Her funeral was attended by most of the nursing staff of No. BGH, as well as the matron and many of the nurses from the 2/2nd AGH, especially those nurses from Western Australia. Also attending were 2/2nd AGH medical officers Captain Alfred Vivian, who had lived in Albany for a time, and Major Joseph Stubbe from Perth. The services in the hospital chapel and at the graveside were conducted by Padre Waterman, a Church of England chaplain from the 2/2nd AGH. The ‘Last Post’ was sounded by a bugler from the Royal Air Force.

After Hilary’s death, Captain Vivian wrote to Margaret and Robert Glazebrook expressing the sympathy of Hilary’s friends in the Middle East, as reported in The Albany Advertiser on 8 December 1941. He told them that Hilary’s bright disposition had made her many friends overseas and that her death was felt deeply by all.

On 28 November the Glazebrooks received official notification of Hilary’s death from the War Office.

Sarah Davidson died in hospital on 29 November. Also known as Sadie, Sarah was a New Zealand nurse who had trained at the Auckland Hospital from 1929 to 1933. Around 1938 she moved to England to work and joined the QAIMNSR on 21 January 1940. She too was buried at the British War Cemetery in Kantara.

Lest we forget.

SOURCES

- Ancestry, various collections, including ‘UK and Ireland, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890–1960,’ ‘UK & Ireland, Nursing Registers, 1898-1968.’

- BBC, WW2 People’s War, ‘Ken Hulbert – RAMC – Sudan and the Ambulance Train’ (Anne Richards, 13 Nov 2005).

- Britannica (website), ‘Munich Agreement.’

- The British Journal of Nursing (Vol. 90, 14 Jan 1942, p. 14), ‘The Passing Bell.’

- Carnamah Historical Society and Museum, ‘Western Australian Nurses 1919–1949.’

- Greek Veterans: The Brotherhood of Veterans of The Greek Campaign 1940–1941 (website), ‘Nursing Sister Jane Pugh TANS, 26th British General Hospital, Athens.’

- Imperial War Museum, ‘How Italy Was Defeated in East Africa in 1941.’

- National Archives of Australia.

- P&O Heritage (website), ‘Bendigo (1922).’

- Scotland’s People, ‘Margaret Melville.’

- Wellcome Collection, ‘In command of No. 16 British General Hospital at Gebeit in the Sudan, Nov 1940-May 1941,’ RAMC/478/2.

- Wikipedia, ‘Western Desert campaign.’

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS

- The Albany Advertiser (WA, 1 Mar 1916, p. 1), ‘Advertising.’

- The Albany Advertiser (WA, 17 Apr 1918, p. 3), ‘Scots Church Sunday School Prize Distribution.’

- The Albany Advertiser (WA, 9 Dec 1922, p. 3), ‘Local and General News.’

- The Albany Advertiser (WA, 29 Apr 1930, p. 2), ‘Personal.’

- The Albany Advertiser (WA, 23 Mar 1936, p. 1), ‘Social and Personal.’

- The Albany Advertiser (WA, 20 Oct 1938, p. 4), ‘In England During the Crisis. Letter from Sister Glazebrook.’

- The Albany Advertiser (WA, 8 Apr 1940, p. 1), ‘Sister Glazebrook.’

- The Albany Advertiser (WA, 1 Dec 1941, p. 1), ‘Sister Glazebrook.’

- The Albany Advertiser (WA, 8 Dec 1941, p. 4), ‘Sister Glazebrook’s Death: Details of Accident.’

- The Albany Despatch (WA, 18 Dec 1924, p. 2), ‘Albany Continuation Classes.’

- Bay of Plenty Times (NZ, Vol. LXIV, Issue 11979, 21 Mar 1936, p. 3), ‘A London Pride.’

- Daily Commercial News and Shipping List (Perth, 27 Mar 1936, p. 2), ‘Fremantle Departures.’

- The Daily News (Perth, 28 Dec 1935, p. 11), ‘Women Will Be Interested to Know That.’

- The Daily News (Perth, 24 Mar 1936, p. 8), ‘Happenings in the Social Round.’

- The Daily News (Perth, 15 Apr 1937, p. 8), ‘Hepzibah’s Gossip.’

- The Daily News (Perth, 7 Jun 1937, p. 6), ‘What a Day!’ W A. Girl’s Coronation Impressions.’

- The Daily News (Perth, 19 Aug 1937, p. 10), ‘Stocking Repairs.’

- The Daily News (Perth, 12 Nov 1937, p. 15), ‘W.A. Women Abroad.’

- The Daily News (Perth, 22 Oct 1938, p. 5), ‘Food for Gossip.’

- The Daily News (Perth, 16 Apr 1940, p. 1), ‘Perth Nurses Go to Near East.’

- Ellesmere Guardian (NZ, Vol. LIX, Issue 89, 8 Nov 1938, p. 4), ‘New Nursing Service.’

- The Herald (Melbourne, 10 Jan 1940, p. 14), ‘Australian Nurses on Thames.’

- Levin Daily Chronicle (NZ, 28 Aug 1933, p. 5), ‘Nursing by the Hour.’

- Listening Post (Perth, 15 Jan 1941, p. 11), ‘Personalities.’

- Mount Barker and Denmark Record (WA, 16 Mar 1933, p. 4), ‘Personal.’

- Mount Barker and Denmark Record (WA, 26 Jul 1934, p. 1), ‘Personal.’

- Mount Barker and Denmark Record (WA, 5 Sept 1935, p. 6), ‘Personal.’

- Mount Barker and Denmark Record (WA, 2 Jan 1936, p. 1), ‘Social and Personal.’

- Mount Barker and Denmark Record (WA, 7 Aug 1941, p. 5), ‘Albany Nurse Visits Asmara.’

- Mount Barker and Denmark Record (WA, 8 May 1947, p. 12), ‘Obituary.’

- The Newcastle Sun (NSW, 16 Apr 1940, p. 4), ‘Australian Nursing Sisters.’

- Northern Times (Carnarvon, WA, 13 Mar 1935, p. 2), ‘Derby News.’

- Northern Times (Carnarvon, WA, 27 Mar 1935, p. 5), ‘Derby News.’

- Northern Times (Carnarvon, WA, 29 May 1935, p. 4), ‘Broome News.’

- Northern Times (Carnarvon, WA, 11 Dec 1935, p. 2), ‘Social and Personal.’

- The Sun (Sydney, 17 Sept 1936, p. 44), ‘Preliminary Training.’

- Sunday Times (Perth, 11 Nov 1928, p. 7), ‘Out of My Post Bag.’

- The Townsville Daily Bulletin (Qld., 26 Oct 1938, p. 12), ‘New Zealand Nurse.’

- The West Australian (Perth, 24 Mar 1932, p. 21), ‘Country News.’

- The West Australian (Perth, 26 Mar 1936, p. 9), ‘Latest Social Activities.’

- The West Australian (Perth, 9 Apr 1940, p. 4), ‘Roundabout.’

- The West Australian (Perth, 29 Apr 1941, p. 5), ‘Woman’s Realm.’

- The West Australian (Perth, 10 May 1941, p. 12), ‘An Australian Nurse Abroad.’

- The West Australian (Perth, 4 Dec 1941, p. 5), ‘Woman’s Realm.’

- Western Mail (Perth, 22 Aug 1946, p. 4), ‘These People.’

- The West Wyalong Advocate (NSW, 2 Sept 1940, p. 4), ‘Australian Nurse.’

- The Wiluna Miner (WA, 17 Mar 1934, p. 3), ‘Wiluna Hospital Board.’

- The Wiluna Miner (WA, 5 Dec 1941, p. 2), ‘Death on Active Service.’