AANS │ Sister Group 1 │ Second World War │ Malaya │ 2/10th Australian General Hospital

Family Background

Dorothy Gwendoline Howard Elmes was born on 27 April 1914 in Armadale, Melbourne. She was the daughter of Dorothy Jean Howard (1876–1965) and Robert Maynard Elmes (1877–1956).

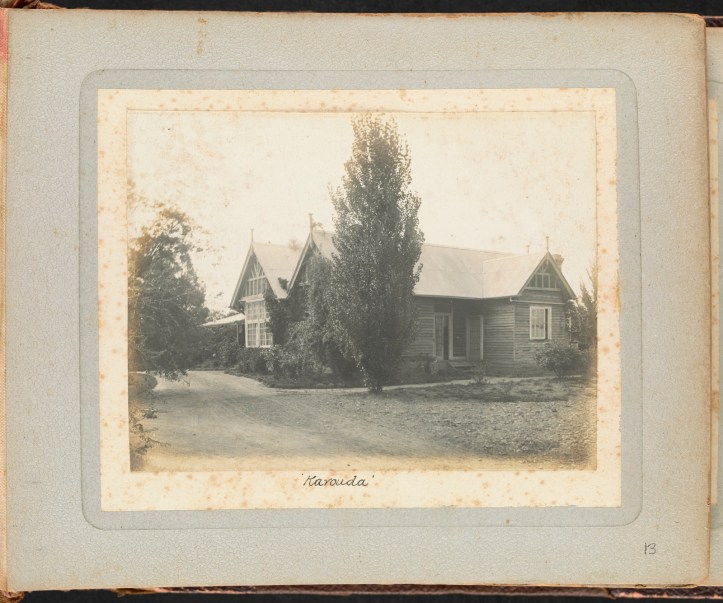

Dorothy Howard, one of twelve children, was born in Kew, Melbourne, and later lived in Cheshunt, in northeastern Victoria’s King Valley. Her father, Frederick William Howard, was a wealthy stock and share broker and owned a 142-acre estate on the King River between Cheshunt and Whitfield known as ‘Karouda.’

Robert Elmes was born in Berwick, then a town to the east of Melbourne and now an outer suburb. His father, Thomas Elmes, was a surgeon and in his later years a Justice of the Peace in Berwick. In early 1900 Robert sailed with his brother Frederick to South Africa, where they hoped to join their brother, John, and fight in the Second Boer War. In due course Robert returned to Australia and by 1908 was living in Cheshunt as a farmer.

On 31 August 1909 Robert and Dorothy were married at Karouda. In 1911 they came down to Armadale in Melbourne for the birth of their first child, Beatrice Jean, known as Jean, and returned two years later for the birth of their second, Dorothy Gwendoline. By now the family was living in Whitfield in the King Valley, where Robert was running a pig farm.

EARLY LIFE

Dorothy Gwendoline went by her second name, as was common among girls named after their mothers. She called herself Gwenda as a teenager and signed her name as ‘G. Elmes’ as an adult. She was known as ‘Bud’ and sometimes ‘Benda’ within her family.

As a child, Gwenda moved around a great deal. In 1916 the family relocated to Stony Creek, near Meeniyan in the Gippsland region of Victoria, where Robert worked as a farm manager. The Elmeses moved back to Cheshunt in 1918, and Robert began to farm tobacco. In the same year, Gwenda’s mother was voted president of the local branch of the Red Cross Society. In 1922 the family was living in Melbourne and by 1924 had returned to Cheshunt.

The Elmeses now lived in the old Howard residence, Karouda, which had been sold after the Howard estate was subdivided some years before. Robert returned to tobacco farming, and Gwenda and Jean attended Degamero State School. After a bushfire destroyed the school building in February 1927, instruction was given in the Cheshunt Hall. It was not until May 1929 that the school reopened as Cheshunt State School.

In the same month that the school reopened, Gwenda penned a delightful letter to the ‘Country Bees’ Columns’ of The Countryman, a rural Victorian weekly newspaper that ran for five years in the 1920s. Her letter was printed on 24 May and read as follows:

Karouda, Cheshunt.

Dear Queen Bee, – I have not written to you for such a long time that you must have forgotten who I am. I am going on for the drawing competition. Do you think you could get me a correspondent in America and Scotland about 15 years old? Could you please tell me my number, as I have forgotten it? I am in the eighth grade at school and walk one and a half miles every day. We had a picnic to celebrate the opening of the new school last Friday. In the afternoon the children had races: I won two prizes. The weather up here is still warm, although we had a good fall of rain about three weeks ago. There has only been one frost this year. Love and best wishes to the Hive.

From

GWENDA ELMES.

We do not know whether Gwenda entered the Countryman’s drawing competition, but in 1930 she did enter a competition run by The Australasian newspaper’s ‘Young Folk’s Page.’ She submitted at least four entries across the year in the Class 1 category – in March, July, October and November. Clearly, she had some talent, for three of her drawings were commended, while the fourth was highly commended.

NURSING

All the while Robert Elmes’s tobacco farming was booming, and in July 1935 he was elected president of the Cheshunt branch of the Victorian Tobacco Growers’ Association. In the same year Gwenda, now in her early twenties, decided to go into nursing. She was accepted as a probationer by Corowa Community Hospital and in 1936 passed her Anatomy and Physiology examination with honours. Also passing the exam was Gwenda’s fellow Corowa trainee and friend Clarice Jean Smithenbecker. Clarice, like Gwenda, went by her middle name and was known as ‘Smithy’ among her nursing colleagues. Gwenda in turn came to be known as ‘Buddy.’

In the second half of 1936, Gwenda – or Buddy – contracted diphtheria. After recovering, she took three months’ leave from the hospital to recuperate.

In January 1938 terrible bushfires destroyed several properties around Cheshunt. Among those lost was ‘The Willows,’ the house that Dorothy and Robert Elmes had bought after leaving Karouda. They moved in with Jean and her husband, Arthur Rowland Banks, whom she had married on 26 April 1937.

Despite this awful event, Buddy was able to concentrate on her nursing career and in May 1939 passed her Nurses’ Registration Board examination. Smithy passed too. On 14 December that year Buddy became registered in general nursing.

ENLISTMENT

It was now 1940, and Europe was at war. Patriotic fervour had gripped Australia and prompted a wave of enlistments, and Buddy wanted to play her part. She joined the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) and on 17 December enlisted in the Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF) at Victoria Barracks, Sydney. She was attached to the Emergency Unit of the AANS at the rank of staff nurse and posted to the camp hospital at the Royal Agricultural Society Showground, opposite Victoria Barracks. The Showground had become a centre of recruitment and training for 2nd AIF enlistees.

At the Showground Buddy met a nurse named Kath Neuss. Kath was born in Mollongghip, near Ballarat in Victoria, and grew up near Inverell in northern New South Wales. In January 1941 the two nurses were advised that they would soon be appointed to a medical unit for service abroad and to prepare for embarkation. On 25 January they were granted pre-embarkation leave, and on 31 January, after their return to the Showground, they formally joined the 2/10th Australian General Hospital (AGH).

The 2/10th AGH had been raised at the Showground over January under the command of Colonel Edward Rowden White for service in Malaya, where it would support the 22nd Brigade of the 8th Division, 2nd AIF – the so-called ‘Elbow Force.’ Elbow Force, which would number nearly 6,000 personnel, was being deployed at Britain’s request to join British and Indian troops in Malaya amid rising tensions with Imperial Japan. On 22 September 1940 Japan had begun to move into French Indochina after signing an agreement with Vichy France. Five days later it signed the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy.

Several other New South Wales nurses joined the unit on 31 January, including Joyce Bell, Pat Blake, Pat Gunther, Jess Doyle, Violet Haig, Peg Olliffe and Frances Taylor. They had been posted to outer-urban and regional camp hospitals prior to being marched in to the Showground. Two masseuses (physiotherapists), Thelma Gibson and Edith (Bonnie) Howgate, were also taken on strength that day.

EMBARKATION

On 1 February Buddy, Kath and the other New South Wales nurses and masseuses, together with the male staff members of the 2/10th AGH, boarded the mighty passenger liner turned troopship Queen Mary, which was lying at anchor off Bradley’s Point in Sydney Harbour. Three other New South Wales nurses, Mavis Clough, Winnie Davis and Marjorie Schuman, had boarded four days earlier, despite joining the 2/10th AGH on the same day as the others. They may have been assigned to help set up the unit’s onboard hospital.

At around 1.00 pm that same day the New South Wales nurses were joined on board by a contingent of Queensland 2/10th AGH nurses. Monica Adams, Jessie Blanch, Cecilia Delforce, Iva Grigg, Pearl Mittelheuser, Chris Oxley, Irene Ralston, Florence Trotter and Joyce Tweddell had arrived from Brisbane that morning. Also boarding on 1 February was a contingent of Victorian 2/10th AGH nurses, among them Thelma Bell, Molly Campbell, Marion Cosgrove, Marjorie Crick, Lorna Duthie, Veronica Dwyer, Caroline Ennis, Dot Freeman, Aileen Irving, Nesta James, Mary McMahon, Kathleen McMillan, Betty Pump, Rene Singleton – and Dot Paschke, the unit’s matron.

All the while, nearly 6,000 troops and ancillary personnel of the 22nd Brigade, 8th Division were streaming on board. They had not officially been told their destination, and many thought that they were going to the Middle East. Some, however, had spotted the crates on the wharf marked ‘Singapore’ and concluded otherwise.

On 3 February six more AANS nurses boarded the Queen Mary – those attached to the 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station (CCS), which was under the command of Melbourne surgeon Lt. Colonel Tom Hamilton. South Australians Elaine Balfour Ogilvy, Millie Dorsch, Irene Drummond and Mavis Hannah had been joined in Melbourne by Tasmanian Shirley Gardam and Mina Raymont from South Australia via Tasmania, and then all six had entrained for Sydney. Irene Drummond was sister in charge of the nurses and Mavis Hannah next in seniority. Other medical units to embark on the Queen Mary were the 2/9th Field Ambulance, elements of the 2/2nd Motor Ambulance Convoy and the 17th Dental Unit, none of which had AANS nurses attached.

The QUEEN MARY

Around 1.30 pm on 4 February the Queen Mary moved away from Bradley’s Point and, to the cheers of thousands of onlookers, steamed through the Heads and out to sea. The mighty ship sailed in convoy with the Aquitania and the Dutch vessel Nieuw Amsterdam, which had departed at the same time and were carrying thousands of troops to Bombay, from where they would transship to the Middle East. They were under the escort of the Australian cruiser Hobart.

On 8 February the convoy was joined in the Great Australian Bight by the Mauretania, which had embarked from Melbourne and was carrying a contingent of New Zealand troops to Bombay for transshipment to the Middle East. Two days later the ships arrived at Fremantle’s outer harbour, and two more nurses of the 2/4th CCS boarded the Queen Mary. On 12 February the convoy set out again, now under the escort of HMAS Canberra. The following day those on board were officially told that their destination was Malaya.

During the voyage Buddy shared a cabin with Marjorie Schuman. Like Kath Neuss, Marjorie was from a small town near Inverell in northern New South Wales. She and Buddy soon became great friends. Buddy called Marjorie ‘Schuey’ and often referred to her in the letters she wrote from Malaya to her friend Jean Smithenbecker – ‘Smithy.’

On 16 February, in the vicinity of Sunda Strait and to the accompaniment of music and the cheers of those on deck, the Queen Mary left the convoy and steamed off for Singapore escorted by the British cruiser Durban, while the other ships continued to Bombay. On 18 February, the Queen Mary arrived at Sembawang Naval Base, on the north coast of Singapore Island, just across the Strait of Johor from the Malay Peninsula.

The nurses disembarked and were taken to adjacent railway sidings. They gave their names and addresses, were issued with rations, and then entrained for the Malay Peninsula. In the early hours of the following morning, Buddy, Schuey, Kath and their 2/10th AGH colleagues alighted at Tampin and were driven to the Colonial Service Hospital in Malacca. The 2/4th CCS nurses, who had been detached to the 2/9th Field Ambulance, alighted at Seremban, further up the line, from where they were driven to Port Dickson.

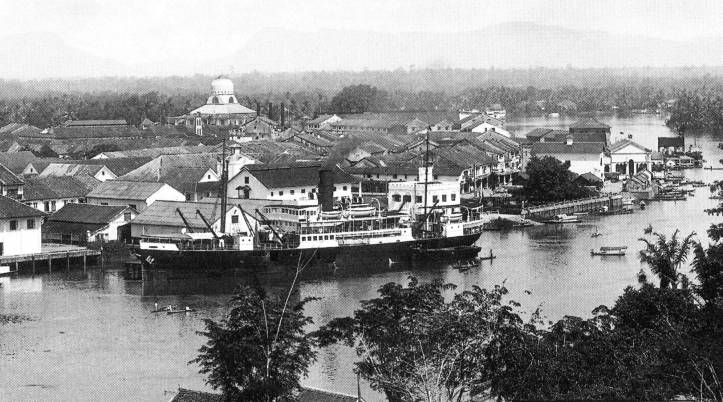

MALACCA

Malacca was an old colonial town on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula, by all accounts very pleasant. The 2/10th AGH had been allocated several wings of the Colonial Service Hospital, a modern, five-storey building located just out of town and set on a slight rise in verdant grounds studded with bougainvillea, frangipani and hibiscus. The nurses were quartered on the fourth floor of one of the wings and enjoyed spectacular views across the lush countryside. They also overlooked tennis courts, which the British nurses of the civilian section of the hospital allowed them to use.

Buddy was a prodigious letter writer, and over the next 11 months wrote to her friend Smithy every week. She began her first letter on 20 February. “We arrived here at some unearthly hour in the morning,” she wrote. “Anyway we are very comfortable. Four of us in a cubicle which all open onto a sort of balcony affair. The country here is absolutely beautiful from an artistic point of view.” She told Smithy that she had been assigned to the operating theatre and that she and the other nurses were endeavouring to learn Malay. She hoped to be able to play tennis soon, as she was feeling the lack of meaningful exercise.

The nurses enjoyed the services of amahs, house maids, who washed the nurses’ clothes, made their beds and generally cleaned up after them. They also had local staff to cook for them and enjoyed comforts provided by the Red Cross, including a sewing machine, a gramophone and books.

When Buddy wrote to Smithy on 26 February, she told her friend what a nice time she was having. “There are a very nice crowd of girls here,” she side, “and all seem very keen on their work.” She told Smithy about the many society invitations that they had received. “Everyone is awfully nice taking us out and inviting us for afternoon tea etc,” she wrote. Over the course of the next few months the nurses were invited to dances, concerts, parties, dinners and bridge nights. They were invited to clubs reserved for Europeans, such as the Malacca Swimming Club, where the nurses went in groups whenever they could organise transport from the hospital. They were invited to play golf, which Buddy enjoyed – her father had, after all, been president of the Cheshunt Golf Club.

Nevertheless, with 6,000 soldiers to look after, there was still work to do, even if the hospital was not running at full pace in those early months. Between April and December, Buddy and her colleagues treated an average of 400 patients a month, generally with tropical infections or training injuries, and occasionally with diseases like malaria or typhus. In the operating theatre Buddy assisted with routine operations.

SINGAPORE

When Buddy was granted leave from 12–14 May, she travelled to Singapore with Schuey and one or two others. On 15 May she told Smithy about it.

Had a nice trip down, the country varies very little only some parts are wetter than others; and slightly more hilly, but it’s the never ending greenness of the place you get SO sick of. However patches of it were beautiful.

In Singapore the nurses checked in to Raffles and spent the day sightseeing.

After having a very nice lunch at Raffles … a Major of some description had a car lent to him [and] took us round to see the sights … after that to the swimming pool which was very nice & most select and really beautiful … After feeding the face we drove through the botanical gardens where there are dozens of monkeys, quite tame scampering about all over the place … then to a Chinese garden which was absolutely beautiful.

That evening they hit the town.

We got back to Raffles for a bath & dinner, Schuey knew a couple of air force lads so we changed into our evening frocks … and went round to various cabarets, stayed at the quietest one most of the evening, & thoroughly enjoyed it. After that went for a drive round again admired the moon etc, had supper and retired to bed.

The following day Buddy and Schuey were just as busy. They

wandered round on our own & did a spot of shopping then was shouted lunch. After that went out to the R. A. A. F. school & saw over various planes & things very interesting afternoon. Afternoon tea at some small café along the beach. After that drove around a bit more before coming back to town. Went to the pictures & saw ‘Escape’ quite good & worth seeing. Schuey & I scarpered back to the hotel & changed our shirts as we were pretty fruity; then out to dinner … Got back at a respectable hour, as those two lads were pretty tired & so were we.

On their final morning, Buddy and Schuey went shopping again and then travelled over the Causeway to Johor, a city in the very south of the Malay Peninsula, to visit the Sultan of Johor’s zoo. After lunch they packed and entrained for Malacca, arriving at the hospital at 8.30 pm.

MORE LEAVE

By June the novelty of her experience in Malaya had begun to wear off and Buddy was feeling removed from the centre of action. In a letter to Smithy written on 21 June she wrote that “we all would like to be somewhere else & really in things. It’s this feeling of never even hearing a gun going off.” This was a sentiment shared by many of her colleagues.

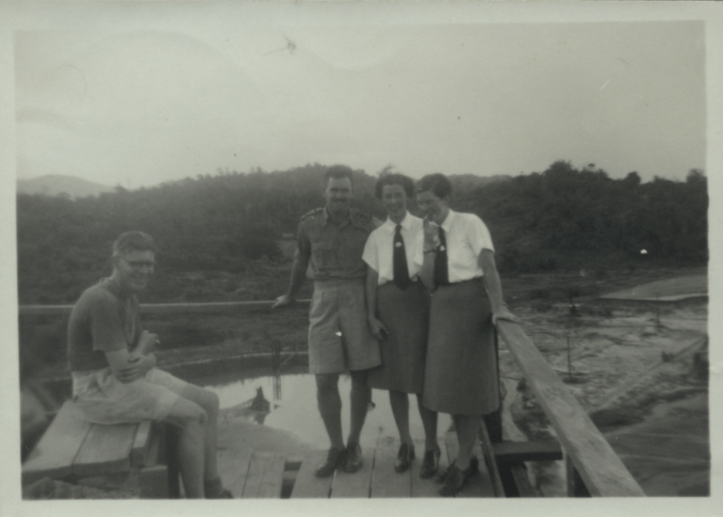

Buddy was granted more leave from 10–14 July. She travelled in a small group to Fraser’s Hill, a typical British hill station lying in the cool highlands north of Kuala Lumpur and characterised by bungalows with red roofs, grey stone walls and white windows, with gardens of roses, carnations and begonias. The nurses left Malacca at 7.00 am and after travelling via Kuala Lumpur arrived at Fraser’s Hill at around 3.00 pm. They spent the afternoon relaxing.

The following morning Buddy and the others went walking over the hills, played tennis in the afternoon, and in the evening went out to a club. They spent the next two days in a similar manner, with the addition of golf, and on 14 July returned to Malacca.

Buddy was granted further leave from 3–10 September and took it with Schuey once again. They travelled north to Kuala Lumpur and had a wonderful time playing golf, walking, dining out and dancing. On their return journey, they missed the train at Kuala Lumpur and did not arrive back in Malacca until 2.00 am in the morning on 11 September.

THE 2/13TH AUSTRALIAN GENERAL HOSPITAL

Meanwhile, following intelligence reports pointing to the vulnerability of Singapore to attack from the north, and amid concerns over Japanese intentions in Southeast Asia and the southwestern Pacific, a second 8th Division brigade, the 27th, had arrived in Malaya on 15 August to augment the 22nd Brigade. Accompanying the brigade were five reinforcement staff nurses for the 2/10th AGH. An earlier contingent of reinforcement staff nurses had arrived in June, among them Betty Jeffrey, and more would arrive as the year drew to a close.

The arrival of the 27th Brigade was followed on 15 September by that of the 2/13th AGH aboard the hospital ship Wanganella. The unit, which had been raised in Melbourne in August at the request of Colonel Alfred P. Derham, Assistant Director of Medical Services (ADMS), 8th Division, had a staff of around 250, including 49 AANS nurses, and was initially based at a Catholic boys’ school, St. Patrick’s, situated in Katong on the south coast of Singapore Island. The arrangement was a temporary measure while the hospital awaited the readiness of its permanent site in Tampoi, in southern Johor State.

On the day of the 2/13th AGH’s arrival in Singapore, 10 of the unit’s nurses were detached to the 2/10th AGH in order to learn tropical nursing from their more experienced peers. They arrived in Malacca the following day. Among them was Mona Tait, whom Buddy had met at the RAS Showground just before she left for Malaya. Another of the detached nurses was Vivian Bullwinkel.

In November Buddy was back in theatre and the rainy season had started. It rained just about every day, which rather ruined Buddy’s tennis routine. She was still managing the odd game of golf, however.

Later in the moth Buddy was granted one last period of leave and from 19–24 November travelled to Singapore with the usual small party. She and her travelling companions struck trouble at Raffles when checking in but were eventually given an enormous room. They shopped, went to the cinema, went out for dinner, dancing and night clubbing, visited the exclusive Singapore Swimming Club, and generally had a marvellous time.

JAPAN INVADES

All the while Japanese troops had been massing in French Indochina, and all the signs pointed to war. On 1 December the codeword ‘Seaview’ was issued, advancing all Commonwealth forces in Malaya to the second degree of readiness. All leave was cancelled and units had to be ready to move at a few hours’ notice to their war stations. This was followed on the evening of 6 December by the codeword ‘Raffles.’ War with Japan was imminent.

It came a little over 12 hours later. In the very early hours of 8 December, a force of some 5,000 troops of the Imperial Japanese Army launched an amphibious assault at Kota Bharu on the Malay Peninsula’s northern coast. At around the same time, Japanese troops landed at Pattani and Singora (Songkhla) in Thailand. At 4.00 am Japanese bombers attacked Singapore Island, killing many people. Elsewhere, Pearl Harbour, Guam, Midway, Wake Island and American installations in the Philippines were attacked and Hong Kong invaded. Japan declared war on the United States, Great Britain, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa. The Pacific War had begun.

Over the coming days, the Japanese troops broke out of their beachhead at Kota Bharu and began to advance southwards on the eastern side of the peninsula. Meanwhile, two other Japanese columns crossed from Thailand into Malaya and moved south along the western side. Although outnumbered, the Japanese were combat-ready and moved rapidly, often by bicycle. They were backed by mechanized units and substantial sea and air power and forced severely outgunned British and Indian troops to retreat before them.

“Suppose by now you have read the papers,” Buddy wrote in her letter to Smithy on 10 December. “We are well in the fun now.” The nurses now had to carry their tin hats and respirators and were not permitted to go out. On 18 December Buddy wrote one of her final letters to Smithy. Japanese forces were 15 kilometres from Penang and seemingly unstoppable. The nurses were now permitted to go out again on a limited basis and Buddy and some colleagues had just celebrated the first anniversary of their enlistment. Unfortunately, swimming was now out of the question, and the rain continued to spoil the opportunities for tennis, but the nurses hoped to have an indoor badminton court set up soon.

Christmas Day arrived, providing a brief diversion from the tension. The nurses enjoyed afternoon tea with the officers and men, after which everyone went to the nurses’ mess for cocktails. Dinner was chicken, trifle and ice cream, and a good time was had by all.

WITHDRAWAL TO SINGAPORE

By 29 December it had become clear that the 2/10th AGH would have to evacuate from the Colonial Service Hospital. Kuala Lumpur had been bombed, and Malacca was now in the direct path of the Japanese advance. Colonel Derham, the ADMS, decided to relocate the hospital to Singapore Island but would need time to find a suitable site.

While Colonel Derham organised the unit’s relocation, most of the staff and all of its patients were farmed out to the 2/13th AGH, which had finally moved to Tampoi. However, 20 of the nurses, including Buddy, Schuey, Matron Dot Paschke, and Nesta James, the next most senior nurse, were detached to the 2/4th CCS, which was now based at the Mengkibol Estate, a rubber plantation five kilometres to the west of Kluang in central Johor whose owners were away in India.

On 7 January 1942 the nurses arrived at Mengkibol by ambulance and were met by Lt. Colonel Hamilton. They were accommodated in the biggest bungalow on the estate – with which they were delighted, having been under the impression that they would be billeted in tents – and taken in hand by Kath Kinsella, one of eight nurses of the 2/4th CCS and the sister in charge.

Matron Paschke left Mengkibol on 13 January with Colonel Edward White, the commanding officer of the 2/10th AGH, to inspect the site chosen by Colonel Derham on Singapore Island for the hospital’s relocation – Oldham Hall, a Methodist boarding school on Barker Road in the Bukit Timah district, near the famous Singapore Racecourse. By 15 January the unit had completed its relocation, and on 17 January Buddy, Schuey and the other 2/10th AGH nurses said goodbye to their peers at Mengkibol and set out for Oldham Hall.

GEMAS

Before they departed, however, Buddy and her comrades had helped to treat Australian casualties of the first battle between 2nd AIF and Japanese troops. Shortly after 4.00 pm on 14 January, B Company of the 2/30th Battalion had ambushed Japanese troops at Gemencheh Bridge, located 11 kilometres to the west of Gemas in southern Negeri Sembilan. That night five wounded men were brought into the 2/4th CCS, two with only minor wounds – confounding expectations of scores of wounded.

However, the following day the main force of the 2/30th Battalion, together with elements of the 2/4th Anti-Tank Regiment, made further contact with Japanese forces outside Gemas, and that evening a convoy arrived at Mengkibol with 36 casualties. By 6.00 am the next morning, 165 cases had been admitted and 35 operations carried out.

Three of the 2/10th AGH nurses had worked with their 2/4th CCS colleagues in theatre overnight. In his book Surgeon Soldier in Malaya, Lt. Colonel Hamilton wrote that one of the three, upon emerging dazed in the morning, remarked on the futility of war. “How heartbreaking to see these fine men, many of them our friends, torn and mutilated for life,” she said. “Why is war so beastly?” In her letter to Smithy dated 20 January, written after her return to the 2/10th AGH, Buddy told her friend that she “did two days work at the C.C.S. which was very interesting.” Perhaps it was she who had posed the timeless question.

“FORTRESS SINGAPORE”

Buddy, Schuey and the others arrived at Oldham Hall in the early afternoon of 18 January. The school was old and dirty but had scrubbed up reasonably well and was situated in beautiful grounds with large trees and lawns, into which air raid shelters had been dug. The nurses’ quarters were located in a nearby bungalow. They were comfortable enough, though somewhat crowded with four to a room, however a radio, a refrigerator and the services of amahs provided adequate compensation. By now the 2/10th AGH had also requisitioned Manor House, a boarding house located a short distance from Oldham Hall. It was to be used for surgical cases.

Meanwhile, the Japanese continued to surge down the peninsula. By 19 January no Commonwealth troops remained between the 2/4th CCS at Mengkibol and Japanese positions, and two days later the unit relocated to its fallback position at Fraser Estate rubber plantation, near Kulai. On 25 January it moved again, to Tampoi, and three days after that crossed Johor Strait from the Malay Peninsula to Singapore Island and occupied the Bukit Panjang English School. The 2/13th AGH, too, was forced to leave the peninsula and by 25 January had moved back to St. Patrick’s School.

On the night of 30 January, the final Commonwealth troops crossed Johor Strait to the island and early the next morning sappers blew a 20-metre hole in the Causeway. Japanese forces reached the northern side of the Causeway soon after and on 2 February began a ferocious artillery bombardment of the island.

The artillery campaign continued relentlessly. On 4 February a number of shells fell a short distance from Oldham Hall, and three days later staff member Private Henry Cushing was hit by a shell while diving into a slit trench and later died of his injuries. Several other staff members were injured. To make matters worse, the large British guns to the south of the hospital were returning fire, so artillery was travelling over the hospital in both directions.

On the evening of 8 February, Buddy wrote to Smithy for the last time.

No news and no letters, haven’t had any from home for a month & from you for a fortnight … there is a lot of news but can’t tell you at the moment; anyway the papers seem to put most of it in print. At the moment am on night duty four nights on … Worked till 2 pm & went on again at seven; but managed to get about an hour & half’s sleep this afternoon, anyway hope for a snooze later as two of us do theatre & we aren’t admitting tonight so things should be pretty peaceful as far as that is concerned. At the moment we are sitting round theatre both writing with two hurricane lanterns wrapped round with blue paper as it’s supposed to be a black out … No news, Cheerio, Bud.

THE FINAL DAYS

Things did not remain peaceful for long. That very day, Japanese forces had begun an intensive artillery and aerial bombardment of the western defence sector of Singapore Island, destroying military headquarters and communications infrastructure. At around 8.30 pm that night, at the very time that Buddy was writing to Smithy, the first wave of Japanese soldiers in amphibious craft began to cross Johor Strait to the west of the Causeway. They came under withering fire from Australian 2/20th Battalion and 2/4th Machine Gun Battalion defenders, but the Australians were hopelessly outnumbered and could not communicate effectively with base. The Japanese continued to cross all night and by the morning of 9 February had established a beachhead on the northwestern corner of Singapore Island.

Tuesday 9 February was a black day indeed. Some 700 casualties poured into the 2/10th AGH. Oldham Hall and Manor House became so overcrowded that men were lying on mattresses on the floor while others waited outside. Despite the fact that the unit had requisitioned further bungalows, it was impossible to cope with the number of admissions, and many were sent on to the 2/13th AGH in Katong, to the British Military Hospital (also known as the Alexandra Hospital), and to the Indian General Hospital. The theatre staff, among them Buddy, now worked around the clock, treating severe head, thoracic and abdominal injuries. There was little respite for staff when off duty, as the constant pounding of bombs and shells meant that sleep was hard to come by.

With Singapore’s fate all but certain, a decision was made to evacuate the nurses. Already in January, following reports of Japanese atrocities in Hong Kong, Colonel Derham had asked Major General H. Gordon Bennett to evacuate the AANS nurses. Bennett had refused, citing the damaging effect on morale. Colonel Derham then instructed his deputy, Lt. Colonel Glyn White, to send as many nurses as he could with Australian casualties leaving Singapore.

The nurses did not want to leave their patients; it was a betrayal of their nursing ethos, and they protested strongly. Ultimately, they had no choice, and on 10 February six nurses from the 2/10th AGH embarked for Batavia with several hundred 8th Division casualties on a makeshift hospital ship, the Wusueh. The following day a further 60 AANS nurses, 30 from each of the AGHs, boarded the Empire Star with more than 2,000 evacuees, mainly British army and naval personnel, and set out for Batavia. Both ships reached the capital of the Dutch East Indies, not without trouble, and the 66 evacuated nurses eventually made it home to Australia.

Sixty-five AANS nurses were left in Singapore but on Thursday 12 February they too had to go. Late in the afternoon, Buddy, Schuey, Kath Neuss and their remaining 2/10th AGH colleagues, plus four of the 2/4th CCS nurses, who had been detached to Oldham Hall, were driven in ambulances through the side streets of Singapore city to St. Andrew’s Cathedral. During one of the heaviest bombing raids the city had yet suffered, they were joined in the cathedral by the 27 remaining 2/13th AGH nurses and the other four 2/4th CCS nurses. When the siren sounded all clear, they set out for Keppel Harbour.

The VYNER BROOKE

The ambulances drove through the ruined city towards the wharves. When they could go no farther, the nurses got out and walked. Fires burned along the waterfront, and the offshore oil installations were ablaze. At the wharves there was chaos, as hundreds of people attempted to board any vessel that would take them.

Eventually a tug took Buddy and her 64 comrades out to a small coastal steamer, the Vyner Brooke. As darkness fell, the ship slid out of Keppel Harbour and after some delay began its journey to Batavia. There were as many as 200 people on board, mainly women and children, but also a number of men. Behind them, thick black smoke billowed high into the night sky.

During the night, Captain Borton guided the Vyner Brooke slowly and carefully through the many islands that lay between Singapore and Batavia, and at first light on Friday 13 February he sought to hide the vessel among them – the better to evade Japanese planes. That morning the nurses were addressed by Matron Paschke, who set out a plan of action in the event of an attack. Essentially, the nurses were to attend to the passengers, help them into the lifeboats, search for stragglers, and only then abandon ship.

Since there were not enough places in the Vyner Brooke’s six lifeboats for everybody, if the nurses could swim, they were to take their chances in the water. They did at least have their lifebelts, and rafts would be deployed too.

Saturday 14 February dawned bright and clear. After another night of slow progress through the islands, the Vyner Brooke lay hidden at anchor once again. The ship was now nearing the entrance to Bangka Strait, with Sumatra to the starboard side and Bangka Island to port. Suddenly, at around 2.00 pm, the Vyner Brooke’s spotter picked out a plane. It circled the ship and flew off again. Captain Borton, guessing that Japanese dive-bombers would soon arrive, sounded the ship’s siren. The nurses, wearing their lifebelts, put on their tin helmets and lay on the lower deck. The ship began to zig-zag through open water towards a large landmass on the horizon – Bangka Island. Soon, bombers appeared, flying in formation and closing fast.

The planes, grouped in two formations of three, flew towards the Vyner Brooke. The ship weaved, and the bombs missed. The planes regrouped, flew in again, and this time the pilots scored three direct hits. When the first bomb exploded amidships, the Vyner Brooke lifted and rocked with a vast roar. The next went down the funnel and exploded in the engine room. As passengers swarmed up to the open air, a third bomb dealt the ship a last, fatal blow. With a dreadful noise of smashing glass and timber, it shuddered and came to a standstill, around 15 kilometres from Bangka Island.

The nurses carried out their action plan. They helped the women and children, the oldest people, the wounded, and their own injured colleagues, among them Kath Neuss, into the three remaining lifeboats, the first two of which got away successfully. However, the Vyner Brooke was now listing alarmingly, and as the third lifeboat was being lowered, it juddered and swayed, and crashed awkwardly into the water. A number of its passengers jumped out and swam, for fear that the ship might fall onto them.

After a final search, the nurses abandoned the doomed ship. They removed their shoes and their tin helmets and entered the water any way they could. Some jumped from the portside railing, now high up in the air, while others practically stepped into the water on the starboard side. Some slid down ropes or climbed down ladders.

Once in the water, some of the nurses clambered onto rafts and some grabbed hold of passing flotsam. Others caught hold of the ropes trailing behind the first two lifeboats or simply floated in their lifebelts. Meanwhile, the Vyner Brooke settled lower and lower in the water and then slipped out of sight. It had taken less than half an hour to sink.

Twelve of Buddy’s fellow nurses died in the attack or were subsequently lost at sea following the attack, including Schuey and Matron Paschke.

BANGKA ISLAND

Sometime on Saturday night Buddy was washed ashore and joined 21 of her colleagues and several dozen other survivors around a bonfire on the beach. As time passed, more people joined them.

On Sunday the survivors learned that Bangka Island had come under Japanese occupation. Lieutenant Sedgeman, the first officer of the Vyner Brooke, proposed surrendering to Japanese authorities but agreed to wait until the following morning before deciding.

Early on Monday morning 16 February, another lifeboat and several life rafts came ashore carrying British soldiers and sailors. There were now perhaps 100 people on the beach, many of whom were injured. The group agreed to surrender, and a deputation left for Muntok to negotiate this. A short while later, most of the civilian women and children followed behind.

Around mid-morning the deputation returned with a squad of Japanese soldiers. The soldiers separated the survivors into three groups: the officers and NCOs, the servicemen and male civilians, and the Australian nurses and remaining civilian women. They took the two groups of men around a nearby headland and shot and bayoneted them. Three managed to escape death, of whom two survived the war.

The soldiers returned to the nurses and civilian women and ordered them to line up on the beach with their faces to the sea. Those who were injured were helped to stand up. They were ordered forward and began to walk into the water. The soldiers opened fire. Buddy, Kath Neuss and 19 other nurses died, together with the civilian women. Vivian Bullwinkel survived and joined the 31 remaining nurses in captivity. Twenty-four came home three-and-a-half years later.

IN MEMORIAM

On 11 April 1950 a beautiful chiming grandfather clock was unveiled in the Nurses’ Dining Room at Corowa Hospital in memory of Buddy. Buddy’s mother was among the gathered guests, but Robert Elmes was too ill to attend. The clock was unveiled by Jean Smithenbecker – Smithy – who by then was Mrs. Jean Neale.

In 1995 two claret ashes were planted on either side of Cheshunt Hall. They memorialise Buddy and her 2/10th AGH colleague Caroline Ennis, who had lived in Cheshunt as a child and was one of the 12 nurses lost at sea.

In memory of Buddy.

SOURCES

- Arthurson, L., ‘The Story of the 13th Australian General Hospital, 8th Division AIF, Malaya,’ Peter Winstanley, Prisoners of War of the Japanese 1942–1945 (website).

- Australian War Memorial, Wallet 1 of 1 – Letters from Sister Dorothy Gwendoline Howard Elmes, 1941–1942, AWM2020.22.162.

- Australian War Memorial, Fall of Singapore – papers of Charles Laurie Price, part 2, AWM2019.22.165.

- Banks, G. (2023), Back to Bangka: Searching for the truth about a wartime massacre, Penguin Random House Australia (Kindle Edition).

- Gill, G. H. (1957), Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 2 – Navy, Vol. I – Royal Australian Navy, 1939–1942, Chap. 12 – Australia Station 1941 (pp. 410–63), Australian War Memorial.

- Hamilton, T. (1957), Soldier Surgeon in Malaya, Angus & Robertson.

- Shaw, I. W. (2010), On Radji Beach, Pan Macmillan Australia.

- Wigmore, L. (1957), Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 1 – Army, Vol. IV – The Japanese Thrust, Part I – The Road to War, Chap. 4 – To Malaya (pp. 44–61), Australian War Memorial.

- Wikipedia, ‘Fall of Singapore.’

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS

- The Age (Melbourne, 17 Feb 1927, p. 14), ‘Dairying Industry.’

- The Age (Melbourne, 17 Aug 1928, p. 1), ‘Advertising.’

- The Age (Melbourne, 13 Jul 1935, p. 22), ‘Wangaratta.’

- The Albury Banner and Wodonga Express (Sep 1936, p. 16), ‘Corowa & District.’

- The Albury Banner and Wodonga Express (30 Apr 1937, p. 46), ‘Weddings.’

- The Albury Banner Wodonga Express and Riverina Stock Journal (24 Jan 1941, p. 20), ‘Corowa.’

- The Argus (Melbourne, 16 Oct 1909, p. 13), ‘Family Notices.’

- The Argus (Melbourne, 22 Oct 1937, p. 14), ‘Other Districts.’

- The Argus (Melbourne, 14 Apr 1938, p. 12), ‘Other Districts.’

- The Argus (Melbourne, 12 Dec 1944, p. 2), ‘Family Notices.’

- The Argus (Melbourne, 28 Sep 1945, p. 2), ‘Family Notices.’

- The Argus (Melbourne, 29 Apr 1948, p. 9), ‘Advertising.’

- The Australasian (Melbourne, 23 Apr 1898, p. 46), ‘Family Notices.’

- The Australasian (Melbourne, 21 Apr 1900, p. 37), ‘War Notes.’

- The Australasian (Melbourne, 5 Apr 1930), p 53), ‘Competition Results.’

- The Australasian (Melbourne, 9 Aug 1930, p. 46), ‘Competition Results.’

- The Australasian (Melbourne, 8 Nov 1930, p. 56), ‘Competition Results.’

- The Australasian (Melbourne, 6 Dec 1930, p. 54), ‘Competition Results.’

- The Australian Women’s Weekly (3 May 1941, p. 7), ‘“They treat us like film stars” says A.I.F. matron in Malaya.’

- Benalla Standard (12 Dec 1924, p. 6), ‘School Examinations.’

- Border Morning Mail (Albury, 23 Jun 1939), p. 6), ‘District Nurses Who Passed Their Examination.’

- The Corowa Free Press (21 Aug 1936, p. 4), ‘Advertising.’

- The Corowa Free Press (14 Apr 1950, p. 5), ‘Sister Elmes Memorial.’

- The Corowa Free Press (10 Nov 1950, p. 4), ‘Sister Elmes Memorial Prize.’

- The Countryman (Melbourne, 24 May 1929, p. 11), ‘A Frost.’

- Goulburn Valley Stock and Property Journal (30 Jul 1919, p. 3), ‘Commercial News.’

- Myrtleford Times and Ovens Valley Advertiser (31 Jan 1945, p. 2), ‘Sister D. G. Elmes.’

- The North Eastern Despatch (Wangaratta, 5 Nov 1913, p. 2), ‘Cheshunt.’

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, 20 Nov 1920, p. 3), ‘Advertising.’

- Rutherglen Sun and Chiltern Valley Advertiser (23 May 1919, p. 3), ‘North-Eastern Land Sales.’

- Wangaratta Chronicle (23 Oct 1918, p. 3), ‘District News.’

- Whyalla News (15 May 1942, p. 1), ‘Naval Officer at Whyalla.’