AANS │ Sister │ First World War │ India & Salonika

FAMILY BACKGROUND

Gertrude Evelyn (or Eveline) Munro was born in Alfredton, a western suburb of Ballarat, Victoria, on 16 August 1882. She was the daughter of Emma Phillis Jenkins (1863–1929) and Alexander Buchanan Munro (1861–1930).

Emma Jenkins was a Ballarat local, whose father, John Jenkins, may have been a miner. Her mother was Emma Kent.

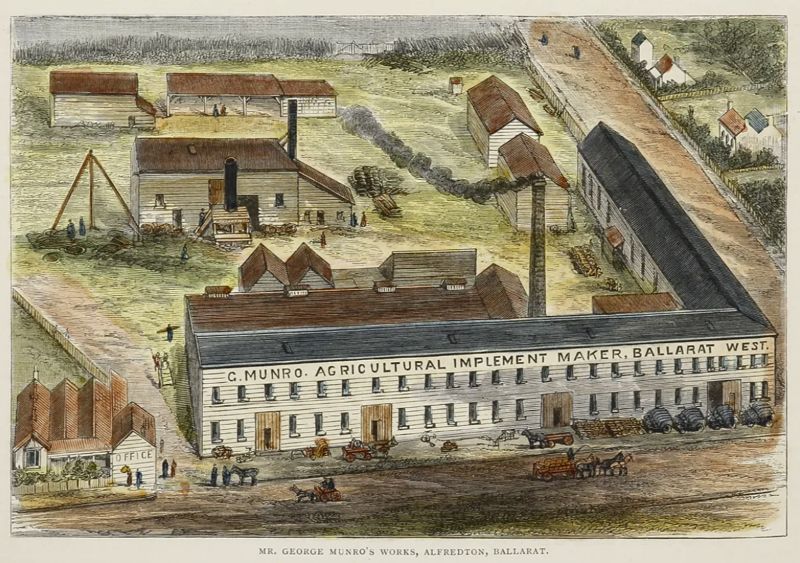

Alexander – or Alex, as he was commonly known – was born in Smythes Creek, a locality around 10 kilometres southeast of central Ballarat. He was the eldest of around 10 children born to Lucinda (Lucy) Marshall and George Munro. After migrating from Greenock in Scotland, George had established a successful business manufacturing agricultural machinery and implements on the corner of Sturt and Gillies Streets in Alfredton.

The year 1882 was a significant one for Alex. He married Emma Jenkins, in August Gertrude was born, and in April his father died, aged only 41, leaving Alex to take a leading role in the future of the business.

In 1884 a second child, George Alexander Buchanan, was born to Emma and Alex.

GEORGE MUNRO & CO.

In mid-1885 the trustees of George Munro’s manufacturing business decided to open a branch in Charlton, in Victoria’s wheat-growing Wimmera district. Alex was to be the manager – and he, Emma, three-year-old Gertrude and baby George moved to Charlton. In a tragic turn of events, little George died later that year.

In 1887 the family’s third child, Ethel Lily, was born, and in September that year Alex and his brother John took over their father’s business from the trustees. Alex moved back to Alfredton to manage the Ballarat branch with John, while long-time employee Mr James Forbes was appointed manager of the Charlton branch. The brothers maintained the name ‘George Munro, Agricultural Implement Maker.’

Over the coming years, three more children were born to Emma and Alex – Alice Isabel in 1888, Ruby Phyllis in 1892 and Kathleen Iris in 1895. During this time, Alex submitted numerous applications for patents for various pieces of equipment, for instance for “an improved harvester” in March 1891.

Around mid-1892 George Munro’s went into hiatus, and in mid-July 1893 the foundry and premises in Alfredton were put up for sale by tender. Each of the brothers then reopened in Ballarat under the name George Munro – Alex on Doveton Street, and John on Peel Street. Meanwhile, Alex, Emma and the children continued to live in Alfredton and by 1896 were living at ‘Atholvilla,’ 5 Gillies Street.

SCHOOL

As a child, Gertrude attended Queen’s College, where she was known as Gertie. Queen’s College was an Anglican girls’ school established in Ballarat in 1876 (and after amalgamating with Ballarat Grammar School to form Ballarat and Queen’s Anglican Grammar School in 1973 is known today as Ballarat Grammar). She was extremely capable academically and conducted herself impeccably.

In 1890 Gertrude completed Form III. In the end-of-year honours she came third in geography, second in writing, second in French and first in conduct. For the next seven years she maintained her excellence in geography and French and demonstrated equal aptitude in English and Latin. Clearly a responsible girl, she was monitress in 1895 and 1896.

One of Gertrude’s fellow pupils at Queen’s was a girl by the name of Val Woinarski, later known as Valerie Zichy-Woinarski. She was four years younger than Gertrude, and two forms lower. Like Gertrude, she became an army nurse, and in 1919 was awarded the Royal Red Cross (2nd Class) for her service. At Queen’s she demonstrated academic brilliance and in her earlier years won practically every honour prize in every subject. Her sister Nina (Alexandrina) was a form above her and just as clever.

NURSING

In her later 20s Gertrude decided to become a nurse and in early 1908 was taken on as a probationer at Ballarat Hospital. In December 1910 she passed her Royal Victorian Trained Nurses’ Association (RVTNA) final examination and graduated in March 1911. Gertrude remained on staff at Ballarat Hospital and in November became registered with the RVTNA in general nursing.

In 1913 Gertrude left Ballarat to train in midwifery at the Women’s Hospital in Carlton, Melbourne. After graduating in March 1914, she became registered with the RVTNA on 2 April.

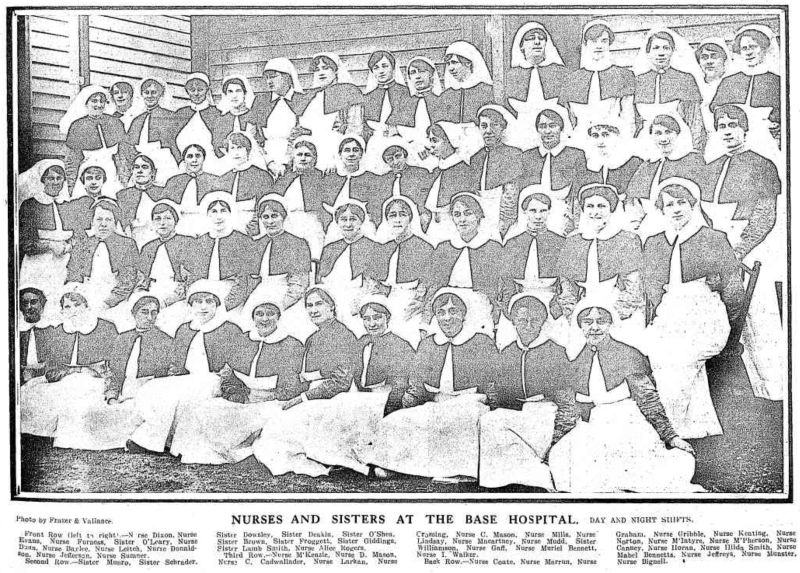

In early 1915 Gertrude applied for the position of matron at Maldon Hospital in Victoria’s central goldfields region. When the selection committee met in early May it chose Elizabeth Thompson, matron of Casterton Hospital for six years, ahead of Gertrude, with four other applicants behind them. The decision of the committee arguably changed the course of Gertrude’s life – for in June, having been passed over for the position of matron, she joined the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) and was attached to No. 5 Australian General Hospital (AGH) on St Kilda Road in Melbourne, commonly known as the Base Hospital.

NO. 5 AUSTRALIAN GENERAL HOSPITAL

No. 5 AGH had opened in the newly completed but as yet unoccupied Police Hospital in March 1915, seven months after Australia had gone to war. The hospital treated Australian Imperial Force (AIF) enlistees still in camps around Melbourne as well as those who had returned ill or injured from the AIF’s camps in Egypt. The hospital initially had 40 beds, with one medical officer and eight nurses, but following the opening of the Gallipoli campaign and the first engagement of AIF troops on 25 April, it expanded dramatically.

On 16 August 1916, after 14 months of home service, Gertrude filled out her attestation form for service abroad with the AIF. She was appointed to the rank of sister and on 22 August boarded the RMS Mooltan at Port Melbourne with 34 other nurses of No. 5 AGH. They were bound for India.

The 35 nurses were among a contingent of 50 nurses who had volunteered to serve as part of the British Indian Service treating sick and wounded British and Indian soldiers of the Mesopotamian Expeditionary Force (MEF) invalided from Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), where they were fighting Ottoman (mainly Turkish) troops. After being treated in military hospitals in southern Mesopotamia, the invalids were transported thousands of kilometres down the Persian Gulf and across the Arabian Sea to Bombay.

THE AANS IN INDIA

The first Australian nurses had arrived in India in July 1916. Following the movement of AIF infantry divisions to France in April 1916, more than 100 nurses based in Egypt had become surplus to requirements. Fifty of them were offered to India, and on 23 July they arrived in Bombay on the Neuralia under Sister Emily Hoadley.

The Australian nurses expected to serve together as a complete staff but instead were split up and posted in groups of three or four or even individually to ‘station’ hospitals, usually of 100 or 150 beds, maintained by British Indian authorities at cantonments (permanent army stations) across India. They were often located in very hot districts and were poorly equipped. Here the nurses treated local garrison soldiers as well as MEF troops discharged from the military hospitals in Bombay to convalesce at their home garrisons. Forty-five of the 50 nurses were transferred to England in January 1917. Two remained in India, while three had died during their service – Staff Nurses Amy O’Grady, Kitty Power and Gladys Moreton.

Meanwhile, following a request from the War Office in London, and with the understanding that British Indian authorities would welcome them, the Australian government agreed in early August 1916 to send as soon as possible another 50 AANS nurses to India directly from Australia, with another 50 to follow a month later. The mobilisation of the nurses began with a call for volunteers, to which the nurses of No. 5 AGH responded unequivocally.

RMS MOOLTAN

The Mooltan departed Port Melbourne at around 4.00 pm on 22 August 1916. Gertrude and her 34 colleagues were under the charge of Sister Gertrude Davis, who had previously been attached to No. 5 AGH before serving in Lemnos and Egypt with No. 3 AGH. One of the 34, Staff Nurse Nellie Isaacs, had trained at the Alfred Hospital in South Yarra and would later serve with Gertrude (Munro) in Salonika. Aside from the nurses, the Mooltan was carrying several hundred Light Horse troops for Egypt and 270 staff of the 1st Australian Wireless Signal Squadron for Mesopotamia.

On 24 August the Mooltan called into Port Adelaide and nine more nurses boarded. A further four boarded in Fremantle four days later. According to the nominal roll, there were now 49 AANS nurses aboard the Mooltan, not 50. From Fremantle the Mooltan set out for Colombo, Ceylon, arriving at around 4.30 pm on 6 September.

After an enjoyable three-night stop, the nurses departed Colombo at midday on 9 September on the Mora, a small steamer operated by the British India Steam Navigation Company. As their vessel pulled away from the harbour, they watched the Mooltan, still at anchor, receding in the distance.

BOMBAY

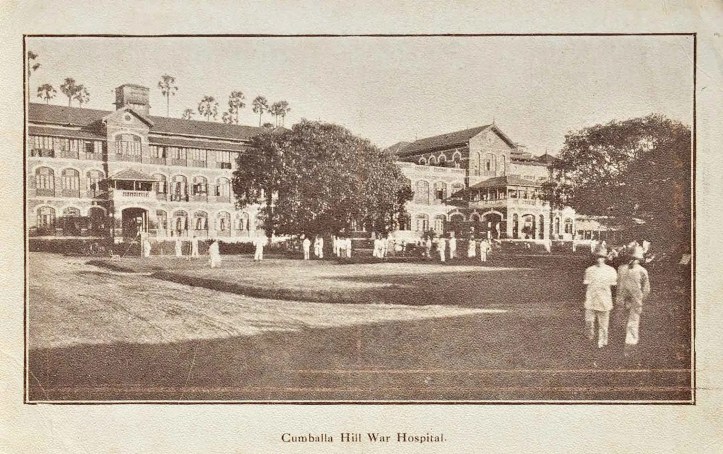

After an uneventful voyage of three days, the 49 nurses arrived in Bombay at 10.00 pm on 12 September. At 11.00 am the next morning they boarded a small boat and in the pouring rain landed at Bori Bunder, a prominent port and warehouse precinct, where Victoria Terminus was located. They were then split up among hospitals around the city – Colaba War Hospital, Cumballa War Hospital, and a hospital set up in the Taj Mahal Hotel – as well as hospitals further afield. Gertrude was posted to Cumballa, while Nellie Isaacs was posted to Hislop War Hospital, in Secunderabad, 700 kilometres to the east of Bombay.

Cumballa War Hospital was situated on Cumballa Hill, around five kilometres northwest of Bori Bundar, on the other side of Back Bay. It had 600 beds, a mixed nursing staff of British and AANS nurses (initially under a British matron), and British medical officers and orderlies. Its patients were Mesopotamian invalids.

Soon after the nurses’ arrival, Sister Gertrude Davis took charge of the Victoria War Hospital, whose British matron was ill and whose British nurses were in the process of transferring to Mesopotamia. The hospital had been established in May 1916 in the newly built headquarters of the Great Indian Peninsular Railway (GIPR), which were situated next to Victoria Terminus in Bori Bunder. Being so close to the docks, the hospital received the most serious British and Indian casualties from the Mesopotamian theatre. Within 10 days of Sister Davis’s arrival, the remaining British nurses had departed and many of the AANS nurses who had initially been sent to Colaba and Cumballa hospitals had been transferred to the Victoria Hospital.

DECCAN WAR HOSPITAL, POONA

On 14 December Gertrude was transferred to the Deccan War Hospital in the city of Poona. Poona lay 150 kilometres southeast of Bombay in the Western Ghats, the chain of hills that runs down the western side of peninsular India. Due to the city’s elevation, Poona’s climate was more comfortable than that of Bombay. The Deccan War Hospital was based at the College of Agriculture on the northern outskirts of the city and was the larger of two military hospitals in Poona, the other being King George’s Hospital, located in the cantonment area to the east of the older, Marathi core of the city.

The Deccan War Hospital had only 80 beds when, on 8 December 1916, Temporary Matron Teresa Dunne was detailed for duty with six AANS nurses under her. Matron Dunne, who was from Queensland and had previously served in Egypt, arrived in Bombay on the RMS Karmala on 10 October and had then been posted to the station hospital in Rawalpindi. Within three months of Matron Dunne’s arrival in Poona, the hospital had been expanded to 1,200 beds and had around 50 AANS nurses on staff. At first its patients tended to be surgical cases from the Mesopotamian theatre, but as time went on and medical arrangements improved in Mesopotamia, medical cases from the local garrisons began to predominate.

Gertrude remained at the Deccan War Hospital for the next seven months. She was joined there by Nellie Isaacs on 4 February 1917.

In mid-1917 volunteers were called for from among the AANS nurses in India to join a nursing unit in Salonika, Greece. Thirty nurses volunteered, including Gertrude and Nellie, and on 11 July they departed Bombay on the RMS Malwa bound for Egypt. They disembarked in Alexandria on 4 August, relieved in Australian and/or British hospitals for three weeks, and on 24 August embarked on HMT Manitou for Salonika.

SALONIKA

Salonika had become a key Allied base in the fight against German-aligned Bulgaria. In mid-1916 more than 110,000 Serbian troops, forced out of Serbia by Bulgarian, Austro-Hungarian and German forces, joined French, British, Russian and Italian troops in the Greek city and established the Allied Army of the Orient. A score of Allied military hospitals, mainly British, had been set up, and in April 1917 British authorities had asked their Australian counterparts to deploy Australian nurses to Salonika to relieve the British, French and Canadian nurses.

Even though there were no AIF troops in the Allied Army of the Orient, the Australian government was happy to oblige the British request, and on 9 June 1917 the RMS Mooltan departed Sydney with some 140 AANS nurses aboard. Around 90 more embarked in Melbourne, followed by 20 or so in Adelaide, and 5 in Fremantle. When the Mooltan departed Fremantle on 18 June, more than 250 nurses were aboard – matrons, sisters and staff nurses.

The nurses arrived in Egypt on 19 July and after spending a week or so in Cairo departed in contingents for Greece, the first arriving in Salonika on 30 July. This contingent, led by Matron Jessie McHardie White, who had been appointed principal matron in Salonika, took over No. 66 General Hospital (GH).

No. 66 GH was a British base hospital of 800–900 beds in tented wards situated near the village of Hortiach (Chortiatis), which lay around 20 kilometres east of Salonika in the hills around Mount Hortiach. It was somewhat wild country, and the nurses were warned not to venture beyond the bounds of the hospital without an armed escort.

NO. 66 GENERAL HOSPITAL, HORTIACH

The Manitou sailed north across the eastern Mediterranean to the Aegean, then up the Thermaic Gulf, and arrived in Salonika on 27 August. Gertrude and her colleagues disembarked and sometime after 9.00 pm arrived at No. 66 GH.

Only a week earlier a terrible fire had destroyed two-thirds of Salonika’s old city. Government buildings, the post office, houses, streets, and even ships in the harbour were gone, and more than 60,000 people were now homeless and hungry.

Within days of her arrival, Gertrude was promoted to the rank of temporary head sister, while Nellie Isaacs was promoted to acting sister.

One of Gertrude’s new AANS colleagues at No. 66 GH was Staff Nurse Christine Ström from Melbourne, who kept a diary. On 3 September she recorded that the hospital was increasingly busy, while on 18 September she noted that at least 40 stretcher cases had come in by convoy. Despite this, following the failure of an Allied offensive in April that year, the front had largely settled into static trench warfare, with relatively few casualties. There were, however, plenty of medical cases, with malaria particularly prevalent.

In mid-September a frightful storm knocked down several tents and flooded others, and in October the weather began to cool down. There were biting breezes, lots of rain, and lots of mud, and the nurses got around in Macintoshes and gumboots.

In the late afternoon of 27 October, Gertrude accompanied two of her nurses who had contracted malaria to No. 43 GH in Kalamaria, a southern suburb of Salonika on the Thermaic Gulf. Christine Ström also travelled with the party, and afterwards wrote about the trip in her diary:

Beautiful sky – sunsets are lovely here. Beautiful little peeps at Salonique life – Wished it had been lighter and I had had my camera. Full moon and glorious. Sat in front of car going down – inside coming back. Very cold. Got back 8 p.m. had dinner by ourselves. Rumours that some of us are going to the 52nd.

Rumours concerning the transfer of the AANS nurses to other hospitals in Salonika – or even in Egypt, Mandatory Palestine or Italy – had been circulating ever since the nurses’ arrival in Greece. Finally, on 10 November Gertrude, Nellie Isaacs, Christine Ström and others packed up their belongings and at around 3.00 pm were driven in ambulances to No. 42 GH in Kalamaria. They arrived to find a tent hospital only recently established, with some of the wards not yet finished. The following day most of the other AANS nurses came down from No. 66 GH.

WINTER AT NO. 42 GENERAL HOSPITAL

No. 42 GH was located with other base hospitals, including No. 52. Although they were some way out of central Salonika, Kalamaria was still much noisier than Hortiach, and Christine Ström notes that some of the nurses did not much enjoy city noises after country ones, particularly the aeroplanes that flew low over them all day to and from a nearby aerodrome.

City noises were the least of the nurses’ problems, however. The dreadful cold of a Salonika winter, even on the coast, was about to smite them. After being invalided back to Australia in August 1918, Nellie Isaacs recalled the miserable conditions in an interview with the Melbourne Herald printed on 15 October 1918.

We moved down to Kalamaria where we spent the winter. Salonica’s winter climate is something to be remembered. No matter how many clothes we were never comfortably warm. The Vada winds that swept the place sometimes for three weeks without ceasing were terrifying in their velocity. The strength and fierceness of these winds often caused the nurses to faint.

The only way one could be sure of having a morning wash was to use the water out of the hot-water bottle. It was no use relying on taps or ewers, all the water was frozen. If one washed a garment and hung it out to dry, it would stiffen almost immediately. I remember hanging a pair of pyjamas outside my tent. When I looked out again they had frozen and taken on the shape of a scarecrow.

We found that the only way to get about comfortably was to wear two or three pairs of thick stockings, and long woollen gaiters under gum boots. These were supplemented with plenty of warm underwear, a pair of riding breeches, a fleece-lined coat, and a Balaclava helmet. With all the equipment we were not particularly warm and some of the nurses suffered severely from frost bite.

Christine Ström wrote in her diary on 6 December that “It’s just dreadful getting up in the mornings. Thermometers frozen in the carbolic, quinine frozen, – the boys sat round the stove all day – poor lads they can’t keep warm.” The following day was just as bad: “We light the Kero stove when we are off duty – have to, and crowd over it and write letters. It’s just dreadfully cold. Our fingers and toes are most painful in the mornings – nothing will warm them up and doing the charts is a real penance.”

SPRING AND SUMMER

On 24 April 1918 No. 42 GH moved from Kalamaria to Uchantar, around 12 kilometres northwest of Salonika. Gertrude and Christine were still with the unit, but on 2 March Nellie had been transferred to No. 52 GH. By now, spring had arrived, a season to behold, as Nellie recalled in her interview:

In the spring Salonica is a blaze of color, with most beautiful wild flowers in gorgeous shades, covering all the hills and mountain ledges. One sees there the Rose of Sharon – mentioned in the Bible. The bloom is pink and in formation not unlike the Passion Flower. Its perfume is exquisite.

On 19 May Gertrude was admitted to the Red Cross Convalescent Home. She was discharged on 2 June and returned to No. 42 GH at Uchantar. By now spring was giving way to summer, and soon the weather would become infernal. On 1 July Christine Ström wrote that the days were growing “warmer and warmer – some days are too red hot.”

However, a bigger problem by far was the toll disease was taking. For many months the nurses had had little experience of surgical nursing, their patients being nearly all soldiers suffering with malaria or dysentery. The medical staff were just as susceptible.

“GREAT EXCITEMENT ABOUT WAR NEWS”

In her diary entry of 26 September, Christine Ström noted the “Great excitement about war news.” The Bulgarians were in retreat and the fighting would soon be over.

Already on 29 August Christine had written that the “Guns [were] very active on Doiran Fr,” by which she refers to the front line around the town of Doiran (today Dojran in North Macedonia), some 60 kilometres north of Salonika. On 1 September the “Stunt [was] still on,” meaning the fighting was continuing, and Greek and French wounded were being admitted to No. 28 GH, around halfway between Salonika and Uchantar. The front line that had been static for so long was now starting to crack.

On 14 September, French and Serbian forces launched an offensive against Bulgarian positions in the mountains east of Monastir (today Bitola in North Macedonia) and within days achieved a significant breakthrough, shattering the Bulgarian front. On 18 September, British and Greek forces launched attacks on Bulgarian defences at Doiran, which crumbled under pressure. Allied troops advanced rapidly northwards, pursuing the retreating Bulgarian army.

Bulgaria surrendered on 29 September, and the following day an armistice came into effect. That day Christine wrote that “Peace [has been] declared here – great rejoicing we got the news at brekker and somehow the very sheep on the hills with their shepherd seemed infinitely more restful than before.”

ILLNESS

The joy induced by end of the fighting was tempered by the terrible toll that pneumonic influenza – Spanish flu – was beginning to take on the troops and on the staff. On 19 September Christine Ström reported that it was everywhere. At the end of September, wrote Christine, the wards of No. 42 GH and No. 43 GH were full of influenza patients, and dozens of casualties of the fighting were dying of pneumonia at No. 52 GH.

On 1 October Gertrude was admitted to No. 43 GH in Kalamaria with an undiagnosed illness. By 8 October she had been diagnosed with malaria and pneumonic influenza and was considered seriously ill. That day Christine Ström wrote that “Munro [was] very ill indeed [and that] several more of the sisters [were] down with flue [sic] and away to 43. We have 1418 patients and staff of 52 – which is the most unequal [proportion] we’ve ever had.”

Gertrude’s condition continued to deteriorate, and by 9 October she was dangerously ill. She died at 12.10 am on 10 October 1918. “Munro died last night,” wrote Christine.

It seems hardly believable. We all feel that this is the beginning of the end as it were. D.D.M.S. very concerned about the staff here and no. of patients – and all convoys are stopped. We’ve been getting 40 in a night sometimes from the line and all pretty sick – most went to observation. Family very depressed all round, and very tired looking.

Gertrude was buried the following day at the British Military Cemetery in Kalamaria, known today as the Mikra Military Cemetery. She was the first Ballarat nurse to lay down her life while on active service.

In an obituary printed in the Melbourne Herald on 22 October, an anonymous colleague of Gertrude’s recently returned from Salonika (surely Nellie Isaacs) was quoted as saying that when she had last seen her in August, Gertrude was in perfect health but had lost a good deal of her robust condition and had become very thin. Her complexion, however, had retained its bright healthy colour.

Gertrude, Nellie went on to say, had

a most lovable nature and was a general favourite. The news of her death will be received with the deepest regret by all the nurses with whom she has worked and the patients she has tended. I heard a matron of the British Regular Army say that Sister Munro was the type of nurse who would be a comfort to any nursing administrator. She was skilled in her profession, a reliable domestic manager, and a lovable woman.

IN MEMORIAM

On 24 June 1925 Gertrude and other Australian nurses who died during the Great War were remembered at a memorial service held in St. Paul’s Cathedral in Melbourne. It had been timed to coincide with a service held at York Minster in England during which the newly restored Five Sisters Window was rededicated to those servicewomen of the British Empire who had lost their lives during the war.

In late December 1926, Emma Munro, by then 63 years old, received information that an unknown person had erected a tablet over Gertrude’s grave in Kalamaria. The tablet was inscribed with the following words:

In the war cemeteries of Salonika there lies only one Australian, Sister Gertrude Evelyn Munro, of Ballarat, Victoria. She gave her life nursing the sick and wounded British soldiers here, and at the time of her death on October 10, 1918, was acting matron of a hospital of 1600 beds.

In memory of Gertrude.

SOURCES

- Ancestry.

- Australian War Memorial, AIF Nominal Roll – Nurses (Jul 1915–Nov 1918), AWM8 26/100/1.

- Australian War Memorial, Butler Collection, Nurses’ Narratives, Mrs. McHardie White, AWM41 1056.

- Australian War Memorial, Butler Collection, Nurses’ Narratives, Sister Alma L. Bennett, AWM41 942.

- Australian War Memorial, Butler Collection, Nurses’ Narratives, Sister G. E. Davis, AWM41 960.

- Australian War Memorial, ‘Mettle and Steel: the AANS in Salonika,’ Ashleigh Wadman, 13 January 2015.

- Australian War Memorial, Transcript of 1917–1919 Diary of Christine Erica Ström, RCDIG0001344.

- BirtwistleWiki (website), 5th Australian General Hospital.

- Burke, E. K. (ed., 1927), With Horse and Morse in Mesopotamia, Arthur McQuitty & Co.

- Butler, A. G. (1943), Official History of the Australian Army Medical Services, 1914–1918, Vol. III – Special Problems and Services, Section III – The Technical Specialties, Chap. XI – The Australian Army Nursing Service (pp. 527–89), Australian War Memorial.

- The Long, Long Trail (website), ‘Salonika Casualty Evacuation Chain.’

- National Archives of Australia.

- National Library of Australia, ‘No. 5 A.G.H.: a magazine published by the patients and staff of No. 5 Australian General Hospital, St Kilda Road, Melbourne’ (vol. 1, no. 1, 5 Aug 1918).

- Past India (website), ‘Cumballa Hill War Hospital Bombay, 1915 Red Cross Postcard.’

- Public Record Office Victoria, Royal Victorian Trained Nurses’ Association Nurses Register (VPRS 16407/P0001), No. 3, 1,466–2,428, 22 Oct 1910–4 Mar 1915.

- University of Cambridge Digital Library, Fairbank Papers, Salonika Diary 1915-1918 (MS Add.10082-MS Add.10082/10).

- Wikipedia, ‘Vardar Offensive.’

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS

- The Age (Melbourne, 25 Jun 1925, p. 11), ‘Memorial Service Empire Army Sisters.’

- The Argus (Melbourne, 12 Jan 1911, p. 8), ‘Trained Nurses.’

- The Australasian (Melbourne, 7 Nov 1908, p. 64), ‘Family Notices.’

- The Ballarat Courier (Vic., 23 Oct 1918, p. 5), ‘The Roll of Honor.’

- The Ballarat Star (Vic., 10 Jul 1885, p. 2), (no title).

- The Ballarat Star (Vic., 10 Sept 1887, p. 3), ‘Advertising.’

- The Ballarat Star (Vic., 20 Dec 1890, p. 3), ‘Advertising.’

- The Ballarat Star (Vic., 22 Dec 1891, p. 3), ‘Advertising.’

- The Ballarat Star (Vic., 15 Jul 1893, p. 2), ‘Advertising.’

- The Ballarat Star (Vic., 27 Jul 1893, p. 3), ‘Advertising.’

- The Ballarat Star (Vic., 7 Sept 1893, p. 4), ‘Advertising.’

- The Ballarat Star (Vic., 20 Dec 1893, p. 3), ‘Advertising.’

- The Ballarat Star (Vic., 19 Dec 1895, p. 3), ‘Advertising.’

- The Ballarat Star (Vic., 19 Dec 1896, p. 3), ‘Advertising.’

- The Ballarat Star (Vic., 18 Dec 1897, p. 4), ‘Advertising’.

- The Ballarat Star (Vic., 18 Oct 1918, p. 2), ‘Personal.’

- The Ballarat Star (Vic., 19 Oct 1918, p. 1), ‘Late Sister G. E. Munro.’

- The Bendigo Independent (Vic., 4 May 1915, p. 8), ‘Huntly.’

- The Herald (Melbourne, 8 Jan 1927, p. 7), ‘Personal.’

- The Herald (Melbourne, 15 Oct 1918, p. 4), ‘How Nurses Dress the Part When on Foreign Service: Back from the Balkans.’

- The Herald (Melbourne, 22 Oct 1918, p. 5), ‘Gallant Service Ended.’

- The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser (21 Mar 1891, p. 650), ‘Patents Office Transactions.’