AANS │ Sister │ First World War │ Egypt, France, Belgium & England

FAMILY BACKGROUND

Fanny Isobel Catherine Tyson, known in later years as ‘Topsy’ and ‘Tops,’ was born on 7 March 1890 in the district of Balranald in southern New South Wales. She was the fourth child of Theresa Augusta Kelly (1863–1904) and John Tyson (1863–1938).

Theresa Kelly was born in Sandhurst (now Bendigo), the largest town in central Victoria’s goldfields. She was one of 13 children born to Isabella and James Kelly, respectively from County Dublin and County Kildare in Ireland, who married in 1847 and subsequently emigrated to Australia. James Kelly drowned in the Big Hill reservoir south of Sandhurst when Theresa was only six years old.

John Tyson was born on Geramy (sometimes spelt Jeremy) Station, his father’s sheep property situated on the south bank of the Lachlan River around 15 kilometres southwest of Oxley township and 60 kilometres north of Balranald in the southern Riverina region of New South Wales. John’s parents were Emma Adams of Somerset and William Tyson of Northumberland, and he had around 15 siblings and half-siblings, his father having been married previously.

Theresa and John were married on 2 September 1884 in Hay, a town on the Murrumbidgee River 120 kilometres east of Balranald. By now John had gained considerable experience in pastoral management on Geramy, where he was superintendent, and may have met Theresa via the droving route between the southern Riverina and the Victorian goldfields.

Following their marriage, John and Theresa lived at Geramy. In 1885 their first child, Mary Agnes, was born. She was followed by Henry William in 1887, Theresa Adelaide (known as Tess) in 1889, Fanny in 1890 and Annie Magdalene in 1892–1946). There were now five children.

By February 1893 John was overseer at Juanbung Station, a sheep station owned by his uncle James Tyson and situated on the north bank of the Lachlan River opposite Geramy. When James Tyson died in 1898, he was reported to be Australia’s most successful squatter, with an estate valued at £2,000,000 – an incomprehensibly vast sum.

As the decade progressed, Theresa and John added to their family. Emily (or Emma) Marguerite was born 1894, John Patrick in 1896 and Charles Edward in 1898.

EARLY LIFE

In July 1899 nine-year-old Fanny wrote two delightful letters to ‘Red Riding Hood,’ the editor of the children’s column of the Bendigo Independent. Her first letter was printed in August, as follows:

Juanbung Station, Oxley, N.S. Wales, July 5, 1899.

My Dear ‘Red Riding Hood,’ – This is the first time I have written to you. I have four sisters and three brothers. Five of us go to school. We have a governess. I am in the second class. Thursday, if it is fine, we are all going to a picnic in Uncle Tom’s paddock, as it is a little friend’s of ours birthday. I hope we will all enjoy ourselves. I am learning a pretty new piece of music from an opera. Hoping I will hear from you soon, I remain, your little friend, – Fanny Tyson, aged 9 years. P.S. – May I write to you again.

It is likely that by “school,” Fanny meant instruction from the governess on the station, as there appears not to have been a school at Oxley. By “Uncle Tom” she means Thomas Tyson, John’s brother. There were numerous other Tysons in the district too.

Three weeks after writing her first letter Fanny wrote again. Her second letter was printed in September:

Juanbung, Oxley, N.S.W., July 27.

Dear ‘Red Riding Hood,’ – I wrote to you. Did you get my letter? I hope to see it in the paper next time. I am learning a pretty little piece of music. Two of my sisters are writing to ‘Cinderella.’ We are getting some butter. I have four sisters and three brothers. There are five of us going to school, and our governess’ name is Miss Ellis, and I like her very much. She is going into Oxley on Friday to play tennis. I remain, yours truly, Fannie Tyson, aged nine years.

Over the next two years, Fanny gained two more siblings, Nellie in 1900 and Percival James (known as James) in 1902. The family was now complete.

Around this time, John Tyson bought a house in Melbourne – ‘Fenwick’ on Male Street in Brighton, a bayside suburb – which became the family’s city residence. On 2 April 1904 tragedy struck when Fanny’s mother died while staying at Fenwick. She was only 40 years old.

Four years later, by which time Fanny had turned 18, John Tyson married again. On 18 June 1908 he and Ethel Augusta Murphy were wed at a quiet ceremony held at All Saints’ Church in St. Kilda, Melbourne. Subsequently they had three children, Allison in 1909, Audrey in 1910 and June in 1915, all of whom appear to have grown up in Melbourne. At least some of the older Tyson children, on the other hand, remained on the land in New South Wales and did not have contact with their half-siblings. In July 1913 the two youngest, Nellie and James, were living with their grandmother, Emma Tyson, at Geramy Station. When Nellie wrote to ‘Patience,’ the editor of the ‘The Young Folk’ children’s page of The Australasian in mid-1913, she told Patience that she had not seen Alison and Audrey.

NURSING

As a young adult Fanny decided to become a nurse and in October 1911 was appointed as a probationer at Bendigo Public Hospital. Her sister Tess began nurses’ training at Bendigo too, either a little earlier or at the same time. Later, their sister Annie would train at Swan Hill Hospital in Victoria.

In May 1914 Fanny, Tess and a trainee by the name of Effie Mary Garden, who would later serve with the sisters in the Great War, passed the Royal Victorian Trained Nurses’ Association examination. After completing their training, Tess was appointed sister in charge of a private hospital in Colac, and Fanny and Effie remained on staff at Bendigo Hospital.

In August that year, the calamity that was the Great War broke out in Europe. Over the months that followed, thousands of Australian women and men joined the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) for overseas service – the men in combat and non-combat roles, the women as nurses of the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS).

ENLISTMENT AND EMBARKATION

On 20 May 1915 Fanny and Effie applied to join the AANS, each witnessing the other’s application form. At the time Fanny was in charge of the operating theatre at Bendigo and Effie in charge of the Lansell accident ward. Their applications were accepted, and they applied for and were granted leave of absence from the hospital. At a farewell gathering organised by the hospital staff on 22 May, the two nurses were presented with travelling rugs, and early on Monday morning 24 May they left Bendigo on the first train for Melbourne.

Meanwhile, Tess was already on her way to Egypt as a reinforcement staff nurse attached to No. 1 Australian General Hospital (AGH). After applying to join the AANS on 10 May she had been accepted for service abroad and had embarked from Melbourne on 17 May with her No. 1 AGH colleagues on the RMS Mooltan.

Fanny and Effie arrived in Melbourne and on 17 June embarked on HMAT Wandilla. They too had been allotted to the No. 1 AGH as reinforcement staff nurses and, together with 34 other reinforcement staff nurses and 50 other No. 1 AGH personnel, were sailing to Egypt. More than 500 AIF troops boarded the Wandilla in Melbourne as well.

The Wandilla had set out from Sydney on 14 June with 156 AIF personnel on board. After leaving Melbourne the ship called into Fremantle, where a further 50 staff of the No. 1 AGH as well as 218 troops and other AIF personnel embarked. On 25 June the ship departed Fremantle and on 18 July reached Port Tewfik, Suez. Fanny had arrived in Egypt.

No. 1 AUSTRALIAN GENERAL HOSPITAL, HELIOPOLIS

After disembarking, Fanny, Effie and their colleagues entrained for Cairo and arrived some 12 hours later. They were met by motor ambulances and driven to Heliopolis, a newly developed garden suburb on the northeastern outskirts of the city, where the No. 1 AGH was based.

No. 1 AGH had arrived in Egypt in January and had established a hospital in the luxurious Heliopolis Palace Hotel. After opening on 25 January with just a few hundred beds, the hospital expanded ahead of the Gallipoli campaign and continued to expand as the number of casualties ballooned. First, better use was made of the spaces inside the hotel, then tented wards were erected at the nearby Heliopolis Aerodrome and in front of the hotel, and finally nearby buildings were taken over as needed. One of those acquired was a large pleasure resort known as Luna Park, which initially functioned as an enormous overflow ward of the Heliopolis Palace Hotel and eventually became its own hospital, No. 1 Auxiliary Hospital (AH). It was here that Tess Tyson had been detailed for duty.

We do not know, however, where Fanny and Effie were detailed for duty. Perhaps they were sent to the Heliopolis Palace Hotel itself; or to Luna Park to work with Tess; or to one of the other Heliopolis buildings taken over and converted into auxiliary hospitals, such as the Atelier or the Sporting Club. As experienced trauma nurses – Fanny having been in charge of the theatre and Effie the accident ward at Bendigo – they were possibly assigned to a surgical ward, not medical (and indeed, later in France, each was attached to a casualty clearing station). Wherever they ended up, they were soon exposed to the full horror of war. For although they and Tess had missed the deluge of casualties that followed the initial Gallipoli landings, they had all arrived in time for the August offensive.

THE AUGUST OFFENSIVE

In August 1915 a new Allied campaign opened on the Gallipoli Peninsula that was aimed at breaking the deadlock with the opposing Turkish forces. Its objective was to capture and hold two peaks on the Sari Bair Range above Ari Burnu (Anzac Cove) – Chunuk Bair and Hill 971 – which would give the Allies a clear view across to the eastern side of the peninsula. In support of the offensive, Australian troops would launch diversionary attacks at Lone Pine and the Nek; Australian, British, Indian and New Zealand troops would assault Sari Bair; New Zealand troops would assault Chunuk Bair; Australian troops would assault Hill 971; British troops would break out of their beachhead at Cape Helles, south of Anzac Cove; and finally thousands of British troops would land at Suvla Bay, north of Anzac Cove, and attempt to link up with the Allies on the Sari Bair heights.

Between 6 and 29 August tens of thousands of Allied troops were thrown into the offensive. Unfortunately, Turkish forces had had warning of what was coming and had been able to reinforce their positions, and within days thousands of Allied soldiers had been cut down.

From the heights of the Gallipoli Peninsula, the wounded were brought down to the beaches and ferried out to hospital ships waiting offshore. In a letter to her friend Lizzie Ryland written on 29 August, Staff Nurse Beryl Corfield, an Australian nurse appointed to the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service Reserve (QAIMNSR), related her experiences aboard one such ship, the Galeka, which was embarking casualties from Capes Helles. “Of the wounded … I will say nothing,” wrote Beryl,

but you will imagine something of their cut up condition when I tell you we had 50 deaths on the two days run to Malta afterwards. Oh Lizzie … to see men come into your ward with legs off arms off – mouth and tongue or lower jaw blown off you would wonder what it is all for & with whom the great reckoning will be.

The hospital ships took the wounded men to the Greek island of Lemnos, to Malta, and to Alexandria in Egypt. In Alexandria they were admitted to Allied hospitals such as No. 17 General Hospital (GH), a British Hospital, where Edith Blake, another Australian QAIMNSR nurse, was posted. In a letter home written on 20 August, Edith described a night at the hospital after several ships had arrived at port all at once:

How the poor wretches rolled in. No-one went off duty. Stretcher bearers worked till midnight … In the ward I’m in there is not one whole man. They each have either leg or arm missing, some have shoulder shattered as well. You don’t know how thankful I feel that we haven’t a brother, to see these poor mangled men, would make one’s heart ache.

Some of the casualties were sent on from Alexandria to Cairo and ended up in the hospitals of Heliopolis under the care of No. 1 AGH. By the middle of August, Fanny, Effie and Tess were dealing with convoys of men with terrible wounds. In her diary entry of 18 August, their colleague Sister Agnes Isambert wrote that

the wounds are just as awful now as when we had the bad cases before so awfully smelly, some nearly make you sick doing their dressings but a good many seem to be getting on alright, some have had to have their arms amputated. One man had a bullet wound in neck, bullet was removed & wound healed, also a small wound on side of head which was not thought anything of, the man took a Jacksonian fit & they operated on him & found a bullet embedded about 3 inches in his brain it was removed & he is doing splendidly – not much brain tissue destroyed.

By the end of August, it had become clear that the offensive had failed utterly. Thousands of men had been killed or maimed for no territorial or strategic gain whatsoever. Soon, the commander of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, General Ian Hamilton, was replaced by General Charles Munro, who recommended the evacuation of the peninsula. The Gallipoli campaign was effectively over.

Towards the end of the year Fanny contracted mumps and on 11 November was admitted to No. 4 AH, an infectious diseases hospital based at the Egyptian army barracks in Abbassia, east of central Cairo. No. 4 AH was another of those offshoot hospitals of No. 1 AGH that had become largely independent. After a stay of more than a month, Fanny was discharged on 16 December. According to her military record, she subsequently reported for duty at No. 4 Auxiliary Convalescent Depot, which appears to have been the same hospital.

FRANCE

Following the end of the Gallipoli campaign in early January 1916, the services of No. 1 AGH were no longer required in Egypt, and a decision was made to send the unit to Rouen in northern France. On 29 March Fanny, Effie, Tess and 112 other No. 1 AGH nurses, including Matron Mary Finlay, entrained for Alexandria and at 5.00 pm the following day departed the Land of the Pharaohs on HMAT Salta, bound for Marseilles.

The Salta arrived in Marseilles Harbour on the morning of 5 April but for the time being the nurses stayed on board. After a day or two they were granted shore leave and spent two days exploring the city. Then, at around 2.30 pm on 10 April, the nurses and the other staff of No. 1 AGH, along with the unit’s equipment, entrained for northern France. Travelling from Provence to Normandy, they passed through Avignon, Macon, Dijon, La Rocher and Nantes, and arrived in Rouen around midday on 12 April.

No. 1 AUSTRALIAN GENERAL HOSPITAL, ROUEN

Sited on the Seine with access to the sea, Rouen was an important centre of British and Allied medical evacuation and was home to numerous hospitals. Many of these were located at Rouen’s southern racecourse, the Hippodrome des Bruyères (today the Parc du Champ des Bruyères), and it was here that No. 1 AGH established a tented hospital.

While their hospital was being set up, the nurses of No. 1 AGH were split up among British hospitals in Rouen, Boulogne, Étaples, Le Havre and Le Tréport. They had been warned earlier that this would happen but had been told that it was a temporary measure and that they would rejoin No. 1 AGH at Rouen as soon as accommodation was ready for them.

Fanny, Effie and Tess were among those nurses who stayed in Rouen. Fanny was posted to No. 6 GH, sited on the racecourse, and returned to No. 1 AGH on 22 April. Effie and Tess were posted to No. 5 GH, also located on the racecourse, and returned on 17 and 20 April respectively. When No. 1 AGH opened on 29 April with 200 beds available for patients, 48 nurses were back on staff, including Matron Finlay. The other 67, however, remained attached to British hospitals for some while longer.

During the first weeks of May the hospital’s beds filled rapidly, and additional beds were made available. Across the month, 751 patients were admitted, brought in by ambulance train from casualty clearing stations sited close to the front. Of these, 362 were evacuated to England, and there were five deaths. At the end of May, the hospital had 249 patients.

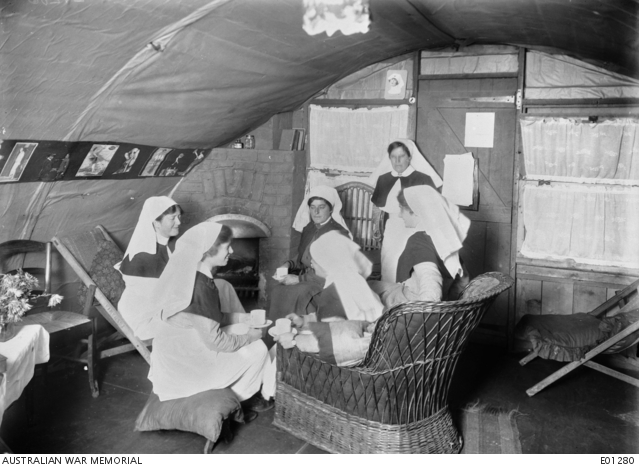

Fanny, Effie and Tess remained together at Rouen for 14 months. During this time, they suffered through the winter of 1916–17, by all accounts one of the harshest on record. The hospital remained predominantly tented, and heating became a problem due to a coal shortage. At one point newly laid water pipes burst, and water became unavailable for a time. Hot water bottles froze, eggs froze, and nurses took their boots to bed to prevent their boots freezing. Frostbite and respiratory illnesses afflicted the staff.

In April 1917 Tess contracted diphtheria and was admitted to No. 25 Stationary Hospital (SH) in Rouen (likely also sited on the racecourse). On 12 May she was transferred to the nurses’ convalescent home at Étretat and returned to No. 1 AGH on 21 May.

No. 2 AUSTRALIAN CASUALTY CLEARING STATION, TROIS ARBRES

On 7 June 1917 the three nurses were separated for the first time since July 1915 when Fanny was detached to No. 10 SH, which was based in the old St. Joseph College on Rue Edouard Devaux in Saint-Omer. She reported for duty the following day and remained at No. 10 SH until 17 July, on which date she was attached to No. 2 Australian Casualty Clearing Station (ACCS) at Trois Arbres.

No. 2 ACCS had opened in July 1916 at the Trois Arbres railhead at Steenwerk, a French town close to the Belgian border and only 20 kilometres south of Ypres. Casualty clearing stations were the closest medical units with surgical facilities to the front, and great care was taken to find suitable nursing staff. As the sister in charge of the theatre at Bendigo Hospital, Fanny was ideal.

At around 10.25 pm on 22 July, five days after Fanny’s arrival, a German aircraft flying low over No. 2 ACCS dropped two bombs. The first fell at the rear of Ward C5, blowing a hole in the ground 5 metres wide and nearly two metres deep. One of the four marquees that comprised the ward was completely destroyed, and the other three badly damaged. Two patients and two orderlies were killed and 15 men wounded, one seriously. Fortunately, the second bomb dropped outside the southern boundary of the ACCS, near the cemetery.

The commanding officer of No. 2 ACCS was of the view that the attack was most likely not deliberate but directed against No. 9 Kite Balloon Section of the Royal Flying Corps, which was located in close proximity to the ACCS. It was a shocking reminder of the hazards of working so close to the front – hazards that were not soon to go away, for a renewed offensive in the Ypres salient, known as the Third Battle of Ypres or the Battle of Passchendaele, was about to begin.

Meanwhile, Effie too had been posted to a casualty clearing station, a British one, in anticipation of the Ypres offensive. On 22 July, as a member of No. 11 Surgical Team, she was detailed for duty at No. 12 Casualty Clearing Station (CCS), which was based at a railhead ironically dubbed ‘Mendinghem’ near the Belgian village of Proven, 15 kilometres east of Ypres. No. 12 CCS had arrived that month with three other British CCSs.

THIRD BATTLE OF YPRES

The Third Battle of Ypres began on 31 July 1917. An initial Allied victory was followed by a month of almost continuous rain, which held up road and rail construction and movement of artillery. During this time a series of minor offensives took place in which British losses were huge. The AIF played only a small part in this first phase of the offensive. After a drastic reorganisation of methods, the second phase began on 20 September, with the AIF now playing a leading role. A series of victories was followed on 5 October by the return of rain, however, and the entire battlefield became one enormous quagmire. The tide turned, and further offensives were pushed back by the Germans with heavy losses. The third phase, the fight for Passchendaele, began on 14 October. After a series of battles in the mud, with Canadian forces taking the lead, Passchendaele was eventually taken. During this phase, the Australians had done little more than hold the line, but had nevertheless sustained heavy casualties from shelling, especially with mustard gas, and from bombing. The offensive officially ended on 10 November. The Allies had advanced a mere 10 kilometres on a 20-kilometre-wide front. More than 250,000 Allied soldiers had died or been wounded, including around 38,000 Australians, with a similar number of casualties on the German side.

Fanny and her colleagues had worked practically nonstop during the course of the offensive. No. 2 ACCS had run three operating tables during the day and two or three at night and had performed thousands of operations. The medical staff had also treated many patients arriving with shocking mustard-gas burns. Until the end of September, the ACCS had continued to come under shell fire, which ended only when No. 9 Kite Balloon Section was relocated away from the hospital. Night bombing raids had also been quite frequent, and a bomb-proof shelter was built for the nurses. They slept in it on moonlight nights.

Effie had worked just as hard at No. 12 CCS. She rejoined No. 1 AGH on 28 October, just before the end of the offensive, and then went on well-earned leave between 7 and 22 November. At the beginning of 1918 she was mentioned in despatches for her distinguished and gallant service while at the CCS and spent the rest of 1918 with the 1st AGH at Rouen before relocating with the unit to Sutton Veny in Wiltshire, England in December.

NO. 5 STATIONARY HOSPITAL, DIEPPE

On 4 January 1918 Fanny departed No. 2 ACCS after five months’ service. She had been posted temporarily to No. 2 AGH at Wimereux, near Boulogne, 100 kilometres west of Trois Arbres. No. 2 AGH, like its sister hospital, No. 1 AGH, had arrived in Marseille from Egypt at the beginning of April 1916 aboard the Braemar Castle. Initially establishing its hospital within the 133-hectare park of Château Musso, which lay in the hills above Marseille, the unit had relocated to Wimereux at the end of June 1916.

Fanny did not stay long with No. 2 AGH. On 11 January she was granted leave and travelled to Cannes in the south of France. Upon finishing her leave, she was posted to A Section, No. 5 SH, a British hospital in Dieppe. (B Section, No. 5 SH was located in Abbeville, 60 kilometres northeast of Dieppe.) Fanny reported for duty on 1 February.

Dieppe was an attractive, hilly town on the Normandy coast. Its casino and several seafront hotels had been taken over by British military authorities to be used as hospitals or convalescent homes. Despite the war, life carried on; shops were open, and the shingle beach was a hive of activity.

On 15 March Fanny was joined at No. 5 SH by Tess, who had remained all this time with No. 1 AGH in Rouen and in September 1917 had been promoted to the rank of sister. During the Ypres offensive she had been in charge of a ward.

Fanny’s life at Dieppe was quite unlike that at Trois Arbres. The hospital took mainly local sick and injured soldiers, not those from the front, and the nurses’ workload was consequently fairly regular and not particularly heavy. However, for a brief period in April, A Section, No. 5 SH, like all Allied hospitals, felt the effects of the German spring offensive.

THE GERMAN SPRING OFFENSIVE

Following the signing on 3 March of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk between Russia and Germany, hundreds of thousands of German soldiers were transferred from the Eastern Front to the Western Front. With its newly freed manpower, on 21 March Germany began Operation Michael, the first in a series of new offensives that became known collectively as the German spring offensive. Initially Operation Michael succeeded in pushing the Allies back towards Amiens, whose rail junction the Germans were aiming to capture, but in early April Australian and British troops counterattacked at Villers-Bretonneux and the German operation stalled. At the end of April, a second German attack on the line at Villers-Bretonneux was repulsed by Australian and British troops. Although more battles were fought before the German spring offensive finally ended in July, the danger of a German breakthrough at Amiens was over.

The thousands of Allied casualties that resulted from Operation Michael flowed from dressing stations on the battlefield to casualty clearing stations and on to stationary and general hospitals. On 22 April, A Section, No. 5 SH prepared for the arrival of large convoys of wounded from Le Tréport, a port town 30 kilometres to the north and another centre of Allied medical activity. Over the following three days, respectively 100, 112 and 99 casualties arrived. Then the rush was over, and Fanny, Tess and their colleagues returned to something more routine.

ENGLAND

On 18 September 1918 Fanny was granted leave and crossed the Channel to England. On 4 October, having remained in England after completing her leave, she was attached to No. 2 Australian Auxiliary Hospital (AAH) in Southall, London. Three days earlier she had been promoted to the rank of sister.

Tess, meanwhile, remained attached to A Section, No. 5 SH until 3 October, then she too crossed the Channel and joined Fanny at No. 2 AAH. On 18 October they were both attached to No. 2 Group Clearing Hospital (GCH) at Hurdcott, near Salisbury in Wiltshire, and arrived the following day. Hurdcott was situated 30 kilometres from Sutton Veny, where the 1st AGH would move in January 1919, with Effie Garden still on staff.

No. 2 GROUP CLEARING HOSPITAL, HURDCOTT

For six months Fanny and Tess worked at No. 2 GCH. The Armistice had been signed on 11 November 1918, bringing the fighting to a halt, and most of the Australian staff had entered their final year of service. Fanny and Tess were no doubt looking forward to returning to Australia in the not-too-distant future.

It was not to be. Seemingly out of the blue, Fanny became ill and on 20 April 1919 – Easter Sunday – was admitted to No. 1 AGH at Sutton Veny. She died that same day at 8.00 pm from cerebral haemorrhage. Tess was with her at the end, as was their brother Charles, who was a driver with the 12th Army Brigade. The Australian War Memorial holds a photograph taken in Ward 7 of No. 2 GCH dated 16 April 1919. The photograph features “Sister Tyson.” It may be Fanny, or it may be Tess; it is difficult to tell. If it is indeed Fanny who is pictured, within four days she had deteriorated dramatically.

FUNERAL

On 23 April 1919 Fanny was buried with full military honours at St. John the Evangelist Churchyard in Sutton Veny. Tess and Charles both attended the funeral, along with a friend, Mr. Fry.

Fanny’s coffin, made of elm with brass mounts, and draped in the Australian flag, was conveyed from the 1st AGH to the graveside on a gun carriage with six AIF men supporting the pall. They were preceded by a firing party from the 1st Australian Training Brigade and followed by a large number of officers, NCOs and other ranks. At the end of the service the ‘Last Post’ was sounded and volleys fired over Fanny’s grave.

Fanny was the second AANS nurse to be buried at St. John’s Churchyard. Six months earlier, Matron Jean Miles Walker RRC had been struck down with pneumonia while working at No. 1 GCH at Sutton Veny and was buried with full military honours. Fanny and Jean had worked together briefly at No. 2 AAH in Southall.

Now they lay together at peace.

SOURCES

- Australian Government, Anzac Portal, ‘Third Battle of Ypres 31 July to 10 November 1917.’

- Australian War Memorial, 2nd Australian Casualty Clearing Station, unit war diary Jul 1917 – Jan 1918.

- Australian War Memorial, Australian Imperial Force unit war diaries, 1914–18 War, No. 1 Australian General Hospital, May 1916, AWM4 Subclass 26/65/2.

- Australian War Memorial, Letters from Sister Corfield during 1915 to her best friend Lizzie Ryland (AWM2017.7.322).

- Australian War Memorial, Unit Embarkation Nominal Rolls, 1914–18 War, ‘AWM8 26/65/3 – 1 Australian General Hospital – 1 to 6 and Special Reinforcements (February 1915 – April 1916).’

- Barrett, J. W. and Percival E. Deane, P. E. (1918), The Australian Army Medical Corps in Egypt, Project Gutenberg.

- Great War Forum, ‘Mendinghem Dozinghem and Bandaghem,’ posted 12 January 2007 by welshdoc in ‘Cemeteries and Memorials.’

- La Malassise, ‘Le pensionnat Saint-Joseph.’

- La Voix du Nord, ‘À la fin du XIXe siècle à Saint-Omer, la rivière des Tanneurs est couverte pour donner place à la rue Édouard-Devaux.’

- The Long, Long Trail, ‘British Base Hospitals in France.’

- The National Archives (UK), ‘No. 5 Stationary Hospital, Jan 1918–Nov 1919,’ WO-95-4100-4.

- The National Archives (UK), ‘Report on the Work of the Australian Army Nursing Service in France,’ E. M. McCarthy, Matron-in-Chief, British Troops in France and Flanders Headquarters, 31.7.19, WO222/2134, via ScarletFinders.

- The National Archives (UK), ‘Work at the Australian Casualty Clearing Stations on the Western Front,’ E. M. McCarthy, Matron-in-Chief, British Troops in France and Flanders, 22.7.19, WO222/2134, via ScarletFinders.

- National Archives of Australia.

- Sedgwick, C. (2015), ‘Sutton Veny, Wiltshire War Graves World War 1: Sister F. I. C. Tyson,’ via the website WW1 Australian Soldiers & Nurses Who Rest in the United Kingdom.

- State Library of Queensland, ‘Agnes Katharine Isambert Diary (item no. 30894/1).’

- Through These Lines, ‘Rouen.’

- Tourisme Marseille, ‘Chateau Musso, la Bâtisse Oubliée du Roy d’Espagne.’

- Vane-Tempest, K. (2021), Edith Blake’s War: The only Australian nurse killed in action during the First World War, NewSouth Publishing, Kindle Edition.

- Wikipedia, ‘German Spring Offensive.’

- Wikipedia, ‘Trench nephritis.’

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS

- The Australasian (Melbourne, 12 Jul 1913, p. 54), ‘The Young Folk.’

- The Ballarat Star (Vic., 19 Jun 1914, p. 6), ‘Trained Nurses.’

- Bendigo Advertiser (Vic., 11 May 1915, p. 8), ‘Nurses Volunteer.’

- Bendigo Advertiser (Vic., 24 May 1915, p. 7), ‘Hospital Nurses Leave.’

- Bendigo Advertiser (Vic., 1 Jun 1916, p. 5), ‘Bendigo Nurses.’

- The Bendigo Independent (Vic., 5 Aug 1899, p. 7), ‘Children’s Column.’

- The Bendigo Independent (Vic., 30 Sept 1899, p. 7), ‘Children’s Column.’

- The Bendigo Independent (Vic., 23 Sept 1914, p. 5), ‘About People.’

- The Bendigo Independent (Vic., 15 Jun 1915, p. 5), ‘Bendigo Medical Assistants.’

- Evening News (Sydney, 7 Mar 1879, p. 3), ‘Mr. James Tyson – The Australian Millionaire.’

- The Herald (Melbourne, 23 Jun 1908, p. 2), ‘The Social World.’

- Kerang Observer (Vic., 9 Jan 1918, p. 3), ‘A Soldier’s Letter.’

- The Queenslander (Brisbane, 11 Nov 1899, p. 934), ‘Classified Advertising.’

- The Riverine Grazier (Hay, NSW, 17 Feb 1893, p. 2), ‘The Poisoning Fatality at Juanbung.’

- The Riverine Grazier (Hay, 19 Apr 1904, p. 2), ‘Family Notices.’

- Riverina Recorder (Balranald, Moulamein, 30 Apr 1938, p. 2), ‘Obituary.’

- The Sydney Morning Herald (6 Feb 1901, p. 7), ‘Sale of Tupra.’