AANS │ Sister Group 1 │ Second World War │ Malaya │ 2/13th Australian General Hospital

FAMILY BACKGROUND

Mary Eleanor McGlade, known as Ellie, was born in Armidale, New South Wales, on 2 July 1902. She was the daughter of Agnes Beatrice Hume (1869–1903) and Francis Aloysius McGlade (1877–1905).

Agnes was born in Crossmichael in Kirkcudbrightshire, Scotland, and was the daughter of Colonel Archibald Hume of Auchendolly, who was a King’s Own Scottish Borderer. She migrated to Australia c. 1900. Her sister Evelyn Mary Hume had migrated to Australia in 1899 following her marriage in Scotland to Walter Charles Scott of Wallalong, near Newcastle in New South Wales.

Francis was born in Belfast in County Antrim, Ireland, where his father was a wealthy landowner. He migrated to Australia in mid-1901. His brothers John Matthew McGlade and Thomas McGlade also migrated to Australia. Francis met Agnes soon after his arrival and on 31 August they were married at St. Mary’s Cathedral in Sydney. They lived with Agnes’s sister Evelyn in Wallalong before moving to Armidale in the elevated Northern Tablelands district of New South Wales, where Ellie was born.

Both Agnes and Francis suffered from tuberculosis and hoped that their health might improve in the rarified air of the uplands. Tragically, it was not to be. Agnes died on 6 November 1903, when Ellie was only one. Francis died in Sydney nearly two years later, on 24 September 1905, having gone there to try a new ‘inhalation cure.’ His brother Thomas, who had been living with him and little Ellie in Armidale, left for Sydney as soon as he heard the sad news. Francis left behind a large circle of friends in Armidale who held him in great esteem and deplored his untimely death.

EARLY LIFE

Francis also left behind poor little orphaned Ellie, who had no siblings. She was cared for initially by a certain Miss Little, and other sympathetic friends of the family, and then came under the guardianship of her aunt and uncle in Wallalong. Evelyn and Walter confided Ellie to the care of the Armidale Ursuline Convent, where she remained until the end of 1921.

Ellie began her schooling in 1910 in the kindergarten class of St. Ursula’s College. At the end of that year, she was awarded first place in Christian Doctrine and won a special prize in Elocution.

During the next 11 years at the college Ellie won many more end-of-year prizes – in history and geography, and particularly in music, where she excelled at violin, piano and singing, as well as in art, craft and doctrinal studies.

In December 1920, Ellie’s second-last year, her work, including dressmaking, embroidery and watercolour painting, was included in the college’s Christmas Exhibition. That year she was awarded third prize in Christian Doctrine and a special prize in Intermediate Violin and Piano. More importantly she gained her Intermediate Certificate.

At the end of 1921, her final year, Ellie came first in Amiability, winning a gold medal. She was awarded a special prize in Advanced Violin and a certificate in Higher Division Singing.

NURSING

Ellie left her home of 15 years at the beginning of 1922. She was possessed of independent means and with her cousin Marion Eleanor Scott, daughter of Evelyn and Walter, travelled to Scotland to visit their grandfather, Colonel Archibald Hume. Ellie then toured Ireland to meet her late father’s relations.

In due course Ellie returned to Australia and decided to train as a nurse. In 1923 she began her training at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney. She passed her final examination in May 1927 and gained her registration in general nursing on 6 October that same year. Later Ellie trained in mothercraft nursing at a Tresillian centre.

All the while, Ellie had remained in the hearts of the Ursuline nuns and was fondly recalled in a 1927 edition of St. Ursula’s Magazine. “Who does not remember Ellie as the winsome little toddler of four years of age to be seen playing around the Convent grounds with Rex, the collie, or her family of dolls, when first she was entrusted to the care of the Ursulines on the death of her parents.”

Nor did Ellie forget the Ursuline Convent. She kept in touch across the 1920s, and in February 1930, when the convent’s new chapel opened, she donated a crucifix to be hung above one of the two side alters.

ENLISTMENT AND EMBARKATION

In 1940, following the outbreak of war in Europe, Ellie volunteered for service with the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS). She understated her age by a year to qualify, as she would have been too old otherwise. She received her call up and enlisted in the Australian Military Forces (AMF) on 13 January 1941 for home service with the AANS. She was appointed to the rank of temporary sister and posted to the camp dressing station at Liverpool, western Sydney, on the same day and two months later was detached to the 113th Australian General Hospital (AGH) at Concord in Sydney’s inner west.

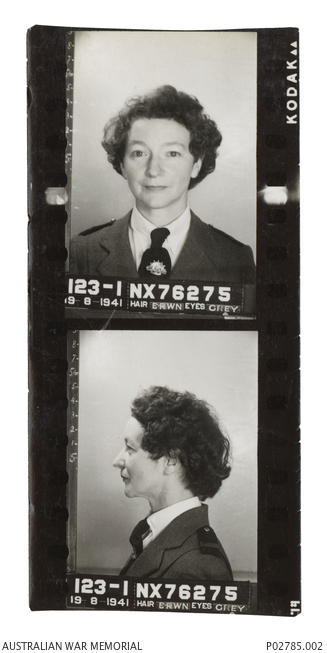

Ellie stayed at Concord until 19 August, when her home service with the AMF was terminated upon her appointment to the Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF), now at the rank of sister. She was attached to the 2/13th Australian General Hospital (AGH) as the unit’s second-most senior sister, behind Sister Julia Powell.

The 2/13th AGH had been raised in Melbourne in early August following a request from Col. Alfred P. Derham, the commanding officer of 8th Division medical services in Malaya, who felt that a second military hospital was urgently needed in view of intelligence reports suggesting the possibility of a Japanese invasion. The 2/13th AGH would join the 2/10th AGH and the 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station (CCS), which had sailed to Malaya on the Queen Mary in February 1941 with many thousands of 8th Division troops.

On 30 August Ellie and 18 other Queensland and New South Wales AANS nurses, including Staff Nurse Veronica Clancy, embarked on HMAHS Wanganella and departed for Melbourne. The ship arrived at Port Melbourne on 1 September, where a further 24 Victorian, South Australian and Tasmanian AANS nurses and around 180 other personnel embarked. A final stop in Fremantle saw seven more AANS nurses come aboard and one stay behind. The 2/13th AGH now had a strength of 49 AANS nurses.

SINGAPORE

The Wanganella arrived at Victoria Dock on Singapore Island on 15 September. Ten of the nurses were detached immediately to the 2/10th AGH, which was based in Malacca on the west coast of the Malaya Peninsula, while the remaining 39 nurses, including Ellie, were transported in sweltering heat to St. Patrick’s School at Katong on the island’s south coast. Here the 2/13th AGH would be based pending the readiness of the unit’s permanent site, a psychiatric hospital in Tampoi on the peninsula.

For three months Ellie and the other nurses enjoyed life in British Malaya. Although she herself seems not to have been, most of her colleagues were rotated through detachments to either the 2/10th AGH at Malacca or the 2/4th CCS at Kajang, where they learned tropical nursing from their experienced peers. They had plenty of free time for social activities and were granted generous periods of leave.

This relatively comfortable life came to a grinding halt on 8 December, when the Imperial Japan Army launched an invasion of Malaya. Just after midnight amphibious troops landed at Kota Bharu in the north of the peninsula, while at around 4.00 am Singapore Island was bombed. Elsewhere, Pearl Harbour, Guam, Midway, Wake Island and American installations in the Philippines were attacked, and Hong Kong invaded. The Pacific War had begun.

WAR

Over the next nine weeks, Japanese infantry, backed by mechanized units and substantial sea and air power, surged down the Malay Peninsula. The severely outgunned British and Indian troops were forced to retreat southwards, and even the entry of Australian troops into combat in mid-January did nothing to arrest Japanese momentum.

The 2/13th AGH, which in late November had finally moved to Tampoi, returned to St. Patrick’s School on 25 January 1942. The 2/10th AGH had completed its relocation to the island 10 days earlier and the 2/4th CCS would follow three days later. By 31 January all Commonwealth troops had retreated to Singapore Island.

When Japanese forces crossed Johore Strait on the night of 8 February and established a beachhead on the island, the end was nigh. Pressure mounted on 8th Division headquarters to evacuate the nurses, and on 10 February the first six nurses embarked with 300 wounded on the makeshift hospital ship Wusueh. The following day a further 60 AANS nurses, 30 from each of the AGHs, boarded the Empire Star with more than 2,000 evacuees, mainly British army and naval personnel, and set out for Batavia. Finally, on Thursday 12 February, Ellie and her 64 remaining colleagues had to go too.

The VYNER BROOKE

The 65 nurses were driven to Keppel Harbour in ambulances and ferried out to the small coastal steamer Vyner Brooke, lying at anchor in the harbour. On board were as many as 200 people – women, children, old and infirm men. As darkness fell, the ship slipped away and began its journey south. After a night and a day of stop-start progress, by Saturday afternoon the Vyner Brooke had reached the mouth of Bangka Strait, a strip of water that separates Sumatra and Bangka Island.

Suddenly, at around 11.00 am, a Japanese plane swooped over, then flew off again. At around 2.00 pm another plane approached before flying off. Captain Borton anticipated the arrival of Japanese dive-bombers and sounded the ship’s siren, then began a run through open water. When a squadron of dive-bombers appeared on the horizon, Borton commenced evasive manoeuvres.

The bombers approached, and the Vyner Brooke zigzagged wildly at full speed. The first wave of bombs missed their target. The planes banked, lined up again, and came in for a second run. One bomb struck the forward deck, another entered the ship’s funnel and exploded in the engine room, and a third tore a hole in the hull. The devasted ship began to sink, 15 kilometres from Bangka Island.

BANGKA ISLAND

After helping passengers and their own injured colleagues into the three viable lifeboats, the nurses abandoned ship. Ellie found herself in the water amid the wreckage, dead bodies and fetid oil and sometime on Saturday night made it to shore. She had likely clambered into one of the lifeboats or caught hold of the ropes that trailed behind them.

Once ashore, Ellie joined a growing group of survivors around a bonfire that had been built on the beach by the occupants of the first of the lifeboats to get away. Among them were 21 other nurses. Sunday was spent considering options, and on Monday morning the group, now numbering around 100 people, decided to surrender to Japanese authorities, who had taken control of the island on Saturday night. A deputation left for the nearest large town, Muntok, to negotiate this. A short while later all the civilian women and children of the group followed behind – save one, Mrs. Betteridge, a British woman whose husband lay among the injured on the beach.

Some hours later the deputation returned with a party of Japanese soldiers. The soldiers separated the survivors into three groups and proceeded to shoot or bayonet them in cold blood.

Ellie and 20 colleagues died on Bangka Island on Monday 16 February 1942. They were shot while walking into the sea. Only Vivian Bullwinkel survived.

Twelve other nurses had died when the Vyner Brooke was attacked or were subsequently lost at sea.

The remaining 31 nurses were taken captive by Japanese soldiers and interned on Bangka Island. They were later joined by Vivian Bullwinkel, who had been hiding in the jungle following the massacre on the beach. The 32 nurses and hundreds of other internees spent the next three-and-a-half years imprisoned on Bangka Island and on Sumatra. Finally, after eight of their comrades had died of disease and starvation, 24 Australian nurses were flown to Singapore on 16 September 1945. They were interviewed upon arrival by Australian journalists, and the following day Vivian Bullwinkel was quoted at length in the Australian press. “We all knew we were going to die,” she said of that shocking day on the beach that decades later became known as Radji. “We stood waiting. There were no protests. The sisters died bravely, and their marvellous courage prevented me calling out when I was hit. I couldn’t let them down.”

In memory of Ellie.

SOURCES

- Ancestry.

- Arthurson, L., ‘The Story of the 13th Australian General Hospital, 8th Division AIF, Malaya,’ as reproduced by Peter Winstanley on the website Prisoners of War of the Japanese 1942–1945.

- Australian War Crimes Board of Inquiry, Sister V. Bullwinkel, 29 Oct 1945.

- National Archives of Australia.

- Shaw, I. W. (2010), On Radji Beach, Pan Macmillan Australia.

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS AND GAZETTES

- The Armidale Chronicle (NSW, 6 Dec 1919, p. 9), ‘St. Ursula’s College.’

- The Armidale Express and New England General Advertiser (26 Sept 1905, p. 5), ‘Events and Rumours’.

- The Armidale Express and New England General Advertiser (NSW, 17 Sept 1945, p. 1), ‘Australian Nurses’ Heroism.’

- The Armidale Express and New England General Advertiser (NSW, 3 Dec 1920, p. 3), ‘Xmas at the Schools.’

- The Catholic Press (Sydney, 15 Dec 1910, p. 35), ‘In the Armidale Diocese.’

- The Catholic Press (Sydney, 22 Dec 1921, p. 4), ‘St. Ursula’s College, Armidale.’

- The Catholic Press (Sydney, 13 Feb 1930, p. 33), ‘Armidale.’

- Catholic Weekly (Sydney, 25 Oct 1945, p. 20), ‘Armidale.’

- Daily Observer (Tamworth, NSW, 20 Feb 1920, p. 2), ‘Intermediate Exams.’

- The Maitland Daily Mercury (NSW, 7 Feb 1936, p. 4), ‘Obituary.’

- New South Wales Police Gazette and Weekly Record of Crime (Sydney, 17 Jul 1901 [Issue No.29], p. 274), ‘Burglaries, &c.’

- The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW, 4 Jun 1927, p. 17), ‘Nurses’ Board.’