AANS │ Captain │ Second World War │ Malaya │ 2/13th Australian General Hospital

Family Background

Jessie Elizabeth Simons, known in later life as Elizabeth, was born at a private midwifery practice on Canning Street in Launceston, Tasmania on 23 August 1911. She was the fourth of eight children born to Mary Ann Muir Lees (1877–1955) and Jabez Peter Simons (1876–1959).

Mary Ann was born in Galashiels, Scotland. On 25 August 1883, at the age of five, she migrated with her mother Elizabeth (40), her father William (40), little brother William (three) and little sister Lillia (one) to Tasmania. The family departed from London on the Cape Clear with 367 other emigrants and arrived in Hobart on 25 October. They caught a train to Launceston and arrived on 27 October with around 35 other passengers from the ship. The Cape Clear was the first steamer to run directly from London to Hobart.

Jabez was born in Birmingham, England. At the age of four he was living in Sutton Coldfield with his mother, Annie Simons (née Edwards), and his father, James Simons, who was a jeweller. His parents were 36 and 40 respectively when Jabez was born, and he remained an only child.

The Simons family migrated to Tasmania sometime between 1881 and 1888. In 1889 Jabez attended the City School in Launceston and in December came third in the mapping examination. By then Annie, James and Jabez were living on Mulgrave Crescent in Lawrence Vale, south Launceston.

In 1896 Jabez began to work at J. E. Piper’s watch and jewellery repair business (“watches, clocks and jewellery cleaned and repaired”) at 130 Charles Street, Launceston. When Mr. Piper died, Jabez continued to run the business. He may have received help from his father, a jeweller by trade. By April 1899 the business had been taken over by Mr. H. Doolan.

In time Jabez met Mary Ann, and they were married at Distillery Creek, a locality just to the east of Launceston, on 30 November 1904. Just five months earlier, on 17 June, Jabez’s mother, Annie, had died at Lawrence Vale. She was buried at Scotch Cemetery in nearby Newstead.

By 1906 Mary Ann and Jabez were living at Young Town, just south of Launceston, and Jabez was working as a drover. On 7 January that year the couple’s first child, Irene Mary, known as Rene, was born. Later that year Jabez’s father, James, died at Lawrence Vale.

In August 1907 their next child, James William, was born. Mary Ann, Jabez and baby Irene had by now moved to Distillery Creek. Two years later, another son, William Frederick, was born at a private midwifery practice on Canning Street, Launceston, perhaps Mrs. Braham’s at no. 78 or Mrs. Newson’s at no. 43.

By the end of 1911, the year of Elizabeth’s birth, the family had moved from Distillery Creek to Nunamara, a small town 15 kilometres to the east that had grown up around a ford on the St. Patrick’s River. The township was known as St. Patrick’s River among other names before ‘Nunamara’ was settled on in 1913, the year the post office opened. Jabez worked as a farmer and in 1914 obtained a Carriers’ Licence.

Over the next 10 years, as the family became integrated into the fabric of the community, four more children were born to Mary Ann and Jabez – Jean Lily in 1914, Donald in 1916, Archibald Raymond Phillip John in 1918 and Colin Geoffrey, known as Tom, in 1921.

Education and Nursing

Elizabeth and her siblings attended Nunamara State School. The school had begun in 1890 as the Lower Patersonia State School and was housed in various buildings. A permanent school building was opened in 1917 and was located near the turn-off to Patersonia. With so many of their children attending over the years, it is not surprising that Jabez and Mary Ann Simons developed a strong association with the school. Jabez presented many annual prizes and Mary Ann often helped out on fundraising stalls.

In 1929, at the age of 18, Elizabeth began nurses’ training at Launceston General Hospital. She passed her Nurses’ Registration Board examination in May 1933 and became registered in general nursing. She then moved to Hobart to begin training at the Mothercraft Home in New Town, established by the Child Welfare Association (CWA) and based on Dr Frederic Truby King’s Plunket system of infant care. In August 1934, after a year’s training, Elizabeth passed her final examination and qualified for her Plunket certificate in mothercraft.

Elizabeth then spent nine months engaged in private nursing, followed by two years at the Lyell District Hospital in Queenstown, in the mining region of central-western Tasmania. It was presumably here that she trained in midwifery, for on 6 August 1937 she gained her registration in that discipline. Elizabeth returned to Launceston General Hospital around October 1937 as sister in charge of the operating theatre.

Enlistment

Elizabeth was working at the hospital on 3 September 1939, when Australia officially entered the Second World War. Thousands of registered nurses across the country volunteered in support of Australia’s war effort, and Elizabeth was among them. On 11 June 1940 she applied to join the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS), 6th Military District (Tasmania) and was accepted in September. A nurse by the name of Shirley Gardam, from Youngtown, Launceston, was accepted into the AANS at around the same time. In the near future she and Elizabeth would spend three years together in captivity.

Elizabeth had her medical on 22 January 1941 and then had to wait more than six months for her call up. Eventually it came, and on 6 August she was appointed to the Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF) at the rank of sister for overseas service with the AANS.

On 27 August Elizabeth boarded a ship bound for Melbourne with fellow Tasmanian AANS appointees Mollie Gunton and Harley Brewer of Launceston and Hilda Hildyard and May Rayner of Hobart. They arrived in the Victorian metropolis and on 1 September were marched in to their unit, the 2/13th Australian General Hospital (AGH).

The 2/13th AGH had been raised in early August at Caulfield Racecourse in Melbourne following a request for an additional AGH to join the 2/10th AGH in Malaya. The 2/10th AGH, together with the 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station (CCS), the 2/9th Field Ambulance, and several smaller medical units, had sailed in February on the Queen Mary with the nearly 6,000 troops of the 22nd Brigade, 8th Division, which was helping to garrison the British colonial possession against Japanese aggression. Once the 27th Brigade was sent to Malaya in August to reinforce the 22nd Brigade, the need for a second AGH became imperative.

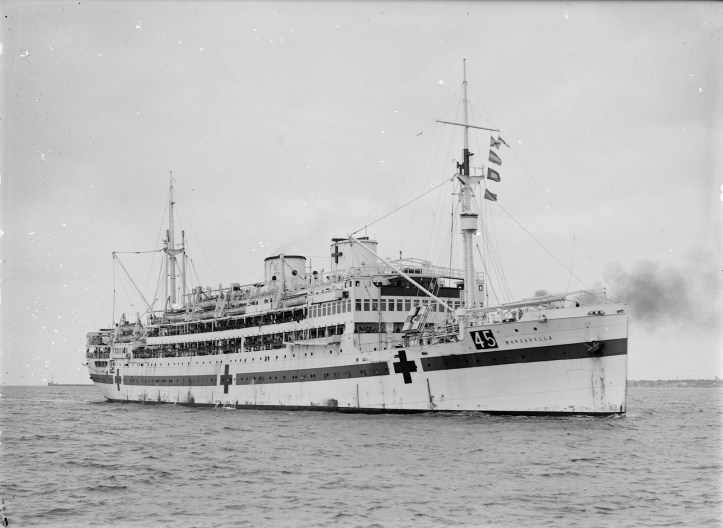

High Majesty’s Australian Hospital Ship Wanganella

The five Tasmanian nurses spent the night of 1 September with 19 Victorian and South Australian 2/13th AGH counterparts at the Lady Dugan Hostel in South Yarra. The next morning the 24 nurses were taken by bus from South Yarra to Port Melbourne, where they boarded HMAHS Wanganella. The newly commissioned hospital ship had left Sydney on 30 August with a contingent of 2/13th AGH personnel from New South Wales and Queensland that included 19 AANS nurses. Later that day the Wanganella slipped out of Port Phillip Bay and headed out into Bass Strait.

Six days later the Wanganella pulled into Fremantle, and as it did so those on board stared in awe at the enormous passenger liners turned troopships Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth, both at anchor in Gage Roads, Fremantle’s outer harbour. They were too massive to enter the inner harbour. The Wanganella remained at anchor for 36 hours, and by the time it set off again late in the day on 9 September, seven more 2/13th AGH nurses had boarded. As one of the cohort had disembarked due to illness, they now numbered 49. The following day, the nurses and other staff of the 2/13th AGH were officially informed that they were headed for Malaya.

Singapore

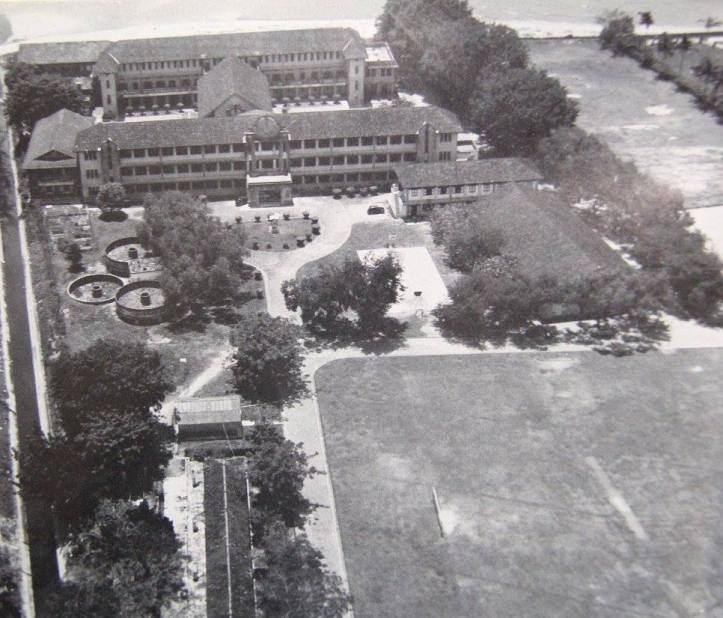

The Wanganella arrived at Keppel Harbour on Singapore Island on 15 September and berthed at Victoria Dock. Elizabeth and most of the nurses disembarked and in sweltering heat were taken by bus to St. Patrick’s School, located in Katong on the south coast of the island, 11 kilometres to the east of Singapore city. Here, the unit would be billeted while it waited to be sent to its permanent base, the Tampoi Mental Hospital near Johor Bahru in the south of the Malay Peninsula.

However, much to their dismay,10 of Elizabeth’s colleagues, including Harley Brewer, Mollie Gunter and May Rayner, did not travel to St. Patrick’s School but were instead detached to the 2/10th AGH and entrained for Malacca on the Malay Peninsula.

Years later, in her book, While History Passed, Elizabeth would write that, upon arrival in Singapore, “we were amazed to find that there was no urgent need for us. Our main job for a while was relieving other nurses on duty at the main army hospital, 2/10th AGH established at Malacca” (Simons, p. 2). Nonetheless, the 10 detached nurses – dubbed the “mobile 10” by Mollie Gunton (quoted in Henning, p. 108) – were learning tropical nursing from their experienced peers. They treated such maladies as tropical ulcers, dengue fever and the odd case of malaria, and upon their return to St. Patrick’s after three weeks passed on their newfound knowledge to the orderlies.

Meanwhile, Elizabeth and the others at St. Patrick’s School attended lectures, were taken on field trips to hospitals on the island and instructed the unit’s orderlies in general nursing techniques. There was plenty of time for leisure: trips to Raffles, sightseeing tours with locals, tennis and golf. What really grabbed them, though, was the Singapore Swimming Club. The nurses were granted access to the exclusive club by dint of their honorary officer status. Elizabeth describes it enthusiastically. “I’ll never forget the Swimming Club – out of this world,” she writes. “A big tiled pool surrounded by tables under beach umbrellas was only the beginning. Showers, post office, electric irons, dining room and dance floors, in fact almost everything we could wish, was there. Good food, immaculate Chinese waiters and a hearty welcome made our visits most enjoyable” (Simons, p. 3).

After the “mobile 10” returned to St. Patrick’s on 6 October, a second rotation of nurses was detached to the 2/10th AGH for three weeks. Elizabeth was among the third rotation, detached between 30 October and 19 November. Shortly after her return to the 2/13th AGH, the unit received orders to proceed to the psychiatric hospital in Tampoi, and by 23 November it had taken over the site from the 2/4th CCS, which moved north to Kluang. The sprawling, single-storey complex had been leased from the Sultan of Johore and was situated on the edge of the jungle; it was not unusual for scorpions, centipedes and other creatures to invade the wards.

Japan Invades

The peace of Elizabeth’s first three months of service was broken on the morning of 8 December, when Japanese forces invaded Malaya from the north and near-simultaneously bombed Singapore. “Before dawn,” she writes, “[Japanese] planes droned high overhead towards Singapore.” The commander of the Japanese invasion force, General Yamashita, had launched what would be an aggressive offensive that quickly overcame the British and Indian troops stationed in northern Malaya. At Tampoi, “tin hats, gas masks and armed guards became the order of the day. Most nights [Japanese] planes went over to bomb Singapore” (Simons, p. 4).

The entry of Australian troops into combat on 14 January 1942 did little to stop the Japanese push southwards. By then the 2/10th AGH was in the process of evacuating to Oldham Hall on Singapore Island, and a week later the 2/13th AGH would follow. After some discussion the unit was ordered to return to St. Patrick’s School. “We commenced the evacuation at four o’clock on the afternoon of January 24th, 1942,” Elizabeth writes, “and thirty-eight hours later were all set up and ready to receive patients at St. Pat’s School” (Simons, p. 4).

In the event, the unit received its first patients even as the wards were being set up and within a week had over 700 casualties. “Night and day,” Elizabeth writes, “the [Japanese] planes roared over to attack the harbour, ack ack guns stuttered half the time, sirens wailed” (Simons, p. 5).

Evacuation

By the end of January, the 2/4th CCS had relocated to the island and most of the troops had crossed the strait. On the night of 31 January, the Causeway connecting the island to the peninsula was demolished. Japanese troops reached the northern shore of Johor Strait soon after and began a ferocious artillery bombardment of the island. They crossed the strait on the night of 8 February and by the morning had established a beachhead on the northwestern corner of island, despite strong opposition from Australian troops. Singapore was doomed.

A decision was made to evacuate the nurses. On Wednesday 11 February, a day after six nurses of the 2/10th AGH departed aboard the Wusueh, the remaining nurses at St. Patrick’s, who had been joined by four of the 2/4th CCS nurses, received orders to assemble in preparation for immediate evacuation. “That was a bolt from the blue,” writes Elizabeth. “It was common knowledge that no real ships were available, certainly not any suitable for hospital ships, and the suggestion that we pull out and abandon our patients sent up our blood pressure. When the call was made [by Matron Irene Drummond] for volunteers from among the nurses to stay behind, we all volunteered. Lists had to be drawn up to designate those who should go and those who should stay” (Simons, p. 6). Twenty-eight nurses and three masseuses (physiotherapists) were chosen. They joined a similar number from the 2/10th AGH and departed later that day aboard the Empire Star. Elizabeth was among those to stay.

On Thursday 12 February, an order came for the remaining 65 nurses to be evacuated as well. At the time Elizabeth was sleeping, as she had been on duty the night before. She was awakened to the sound of shouting and running feet, as nurses ran helter-skelter to prepare for evacuation. She and those with her had only minutes to throw together a few things in a small suitcase, collect their respirators, tin hats and ‘iron rations’, and go.

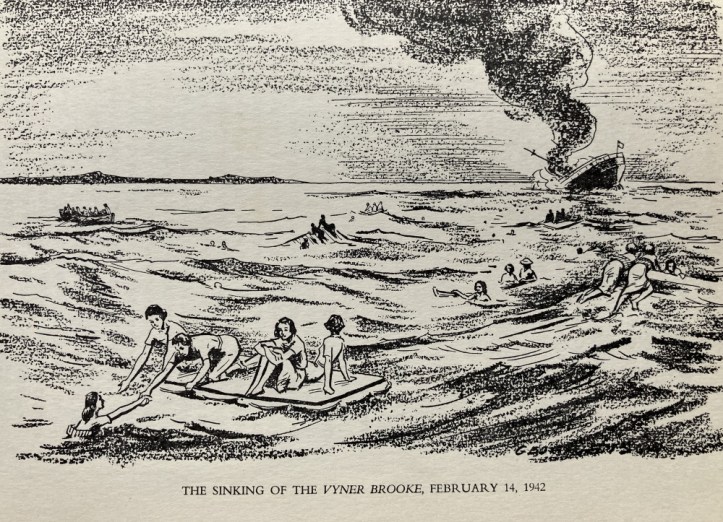

Escape on the Vyner Brooke

The 2/13th AGH and 2/4th CCS nurses were taken by ambulance to St. Andrew’s Cathedral in Singapore city where they joined the remaining nurses of the 2/10th AGH and the other 2/4th CCS nurses. They all drove then “through indescribable ruin, blazing buildings, acrid smoke and abandoned or wrecked cars” to the wharves, where they embarked on small boats and threaded their way “through a congested mass of shipping of all types” to the SS Vyner Brooke (Simons, p. 7). As dusk fell, the small coastal steamer sailed south with as many as 250 passengers aboard, most of them women and children, leaving behind a city in ruins.

On Friday 13 February the Vyner Brooke hid among the hundreds of small islands that line the passage between Singapore and Jakarta, the ship’s first destination. During the day, Matron Paschke summoned the 65 nurses for a conference to formulate a plan of action in the event the Vyner Brooke should be attacked. Later, a single Japanese plane flew over and strafed the ship, punching holes in all the starboard lifeboats.

As night approached, the captain endeavoured to steer the Vyner Brooke towards open water but was forced back by searchlights. “Discreetly,” Elizabeth writes, “the ship turned back behind the screen of islets and our progress, as we crept without lights among scores of tiny islands, was disappointingly delayed” (Simons, p. 12). Around 11.00 am on Saturday 14 February, an aircraft swooped over. There was confusion as to whether it was Japanese, but it was enough to prompt Captain Borton to begin evasive action. “The ship’s engines were now racing at full speed,” Elizabeth writes, “and she zigzagged wildly as the captain adopted the few protective measures available” (Simons, p. 13). To distract herself, Elizabeth continued to read her copy of Ethel Mannin’s Cactus.

The Vyner Brooke Is Sunk

Sometime between 1.00 pm and 2.00 pm, as the Vyner Brooke was approaching the entrance to Bangka Strait, with Bangka Island to the left and Sumatra to the right, Japanese dive bombers approached. In a short period of time 27 bombs were released, some missing the ship by mere inches. As another plane whined down, “the ship lifted and rocked with the vast roar of a bomb exploding amidships” (Simons, p. 13). It had entered through the ship’s funnel and exploded in the engine room. Then another struck the ship, and a third, and the Vyner Brooke was doomed.

After the first explosion, Elizabeth and the other passengers rushed to the upper deck. Then, with her 2/13th AGH colleagues Iole Harper and Vima Bates, Elizabeth went below deck again, reasoning that there was a better chance of reaching the water from there. After briefly turning back for her shoes, she lost the other two, and entered the water alone. “I turned to float in my life belt,” she writes, “and [looked] back on the Vyner Brooke. Swiftly she settled lower in the water, then the stern lifted [and] the ship slipped rapidly out of sight, leaving widening circles in the afternoon sea. Within fifteen minutes of the first hit, no sign remained of the Vyner Brooke but a pair of leaking boats, a few rafts, scattered wreckage and scores of human heads bobbing on the oily sea” (Simons, p. 16).

The Australian nurses held an impromptu meeting in the water, “shouting advice and encouragement to each other … Jenny Greer started to sing, ‘We’re off to see the Wizard’ and the girls joined in” (Simons, p. 16). The currents scattered the survivors over a wide area, and Elizabeth managed to clamber aboard a raft with two British sailors and a radio operator. Soon after, Pat Gunther, who had been badly injured, and Winnie May Davis, both of the 2/10th AGH, were swept up to the raft. As there was no more room, Elizabeth climbed off and helped Pat aboard, then she, Winnie and one of the British sailors alternated between the raft and the water. Three civilian women drifted by; two clung on to the raft and the other, already unconscious, drifted away.

During the night, the group drifted southwards towards the entrance to Bangka Strait and at a certain point came across Japanese transport ships disgorging landing craft crammed with soldiers. The Japanese invasion of Sumatra had begun. Later, Elizabeth and the others saw “a bonfire on the beach and concluded that some of the survivors of the Vyner Brooke had succeeded in getting ashore” (Simons, p. 19). The bonfire had been lit by the passengers of one of the two lifeboats to get away successfully. They were later joined by the passengers of the second lifeboat. Among those gathered around the bonfire were 22 of Elizabeth’s colleagues. Two days later 21 of them would be murdered by Japanese soldiers in what would become known as the Bangka Island massacre.

Dawn brought confirmation of the Japanese invasion. A fleet was anchored off the coast of Bangka Island, and launches were coming and going between the fleet and the shore. Those on the raft waved to one of the launches. It turned around, picked them up and took them ashore. Elizabeth had been in the water for 19 hours.

Prisoners of Japan

Elizabeth and her party were taken by Japanese soldiers to a large cinema in the nearby town of Muntok. There they were placed with hundreds of other prisoners, the survivors of dozens of ships sunk by the Japanese invasion force. To Elizabeth’s great joy she met a group of her own AANS nurses. Some days later, two more nurses, Iole Harper and Betty Jeffrey (2/10th AGH), turned up. They had become lost in a mangrove swamp after reaching the shore. Finally, towards the end of the nurses’ second week of internment, Vivian Bullwinkel of the 2/13th AGH arrived. She had been the only AANS survivor of the horrific massacre.

Of the 65 Australian nurses who had set out from Singapore on the ill-fated Vyner Brooke, 12 were lost at sea and 21 killed in the massacre. Now the surviving 32 began a period of three-and-a-half years as prisoners of war.

During this time, Elizabeth and the other AANS nurses, together with many hundreds of interned women, children and men, were moved between half-a-dozen camps in Muntok and southern Sumatra, each more hellish than the previous. They were subjected to systematic abuse and random acts of violence. They were slapped, yelled at and made to stand in the sun. They were threatened with starvation and, by the end, nearly did starve. They were denied their rights under the Geneva Convention to be treated as prisoners of war.

In March 1943, following the visit of a high-ranking Japanese official, the nurses were permitted to write home, the only time during their whole captivity. In Elizabeth’s lettercard she told her parents that there were 32 of them in captivity and that she was receiving good treatment. She requested vitamins and new glasses. Mary Ann and Jabez Simons received the letter in December that year, the first news they had heard from Elizabeth in nearly two years. At least now they knew she was alive.

By the end of 1943 sickness had become so prevalent among the nurses due to their chronic malnourishment that only the very worst cases could be admitted to the camp hospital. Bronchitis, dysentery and dengue fever were common complaints, and tinea was widespread. During the year Elizabeth had suffered an attack of dengue fever, while Mavis Hannah of the 2/4th CCS, her best friend during their captivity, had suffered beriberi as well as bouts of dengue and dysentery. The nurses had reached the end of their resistance to disease. “On the poor diet,” writes Elizabeth, “we had held out for the first year on accumulated bodily health and resistance, but after that, few of us were ever free from some trouble or other” (Simons, pp. 62–63).

The final two camps, Muntok, on Bangka Island, and Belalau, on Sumatra, were the worst of all. Disease was now rife, and life-saving medicines withheld. The internees began to succumb to illness. By the time Elizabeth and the other nurses were rescued, eight of their comrades had died.

Rescue

On 16 September 1945 the surviving 24 nurses were plucked from the Sumatran jungle by an Australian Dakota aircraft and flown to Singapore. They were driven to St. Patrick’s School and taken into the care of the 2/14th AGH. Soon after they arrived, the nurses enjoyed the luxury of the first beds they had slept in for three and a half years.

After a period of recuperation in Singapore, on 5 October the nurses boarded the AHS Manunda and arrived in Fremantle on 18 October. They were home.

Rescued AANS nurses at a Gracie Fields concert held at the former residence of Japanese General Saito for Australian ex-POWs, Changi area, Singapore, 1 Oct 1945. Left to right: Vivian Bullwinkel (obscured), Beryl Woodbridge, Iole Harper, Elizabeth Simons, Eileen Short, Veronica Clancy, Mavis Hannah. (AWM 118809)

The ship continued to Melbourne. On 24 October Elizabeth disembarked with the Victorian, Tasmanian and South Australian nurses, and they were all taken to Heidelberg Military Hospital. Three days later she flew to Launceston. She spent the weekend with her sister Jean in Trevallyn and was interviewed by the Hobart Mercury. “It seems 1,000 years since I left Launceston,” she said. For the next six weeks or so she divided her time between her sister’s house and the family home in Nunamara.

Life After War

After recovering to the extent possible, and following her discharge from the army, Elizabeth kept herself busy. She resumed her nursing career at the Launceston General Hospital and from 1946 to 1952 was senior sister and assistant matron.

Elizabeth became involved with the Northern Tasmanian sub-branch of the Australian Trained Nurses’ Association. In July 1947 she stood down as president of the sub-branch and was then elected one of three vice presidents. For some years she was a member of the Launceston General Hospital Ex-Trainee Nurses Association, and in later life was patron.

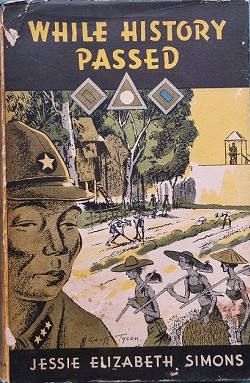

In 1954 the publication of Betty Jeffrey’s book White Coolies, based on her secret diary, and Elizabeth’s own book, While History Passed, brought the story of the Vyner Brooke nurses’ internment in the camps of Sumatra and Bangka Island to a wide audience. While History Passed was based on Elizabeth’s recollections of her experiences as a prisoner of war and was written with a good deal of wry humour and pathos. On 28 May, the day of the launch of her book, an interview with Elizabeth was printed in the Melbourne Argus in which she stated with typical humour, “Yes, it’s my first book – and my last, too, I’d think. I’ve no special literary aptitude; I just wrote what happened.” The day before the launch Elizabeth was delighted to have her former matron-in-chief, Colonel Annie M. Sage, and fellow ex-POWs and friends Vivian Bullwinkel and Betty Jeffrey with her. Like White Coolies, While History Passed was serialised in newspapers around the country following its publication and was republished in 1985 as In Japanese Hands: Australian Nurses as POWS.

In the 1950s Elizabeth resigned from Launceston General Hospital to look after her mother and father. Following the death of her mother in 1955, she sailed to England and worked as a nurse in London, gaining her British and Irish nursing registration on 29 April 1957. In 1959 her father died.

In 1970 Elizabeth married (Henry) Hayman Hookway in Launceston and moved to the town of Boat Harbour on Tasmania’s northwest coast. In 1941 Hayman had married Elizabeth’s sister Irene. In a beautiful turn of fate, Elizabeth now became step mother to her sister’s five children, Oswald, Brian, Irene, Mavis and John.

This Is Your Life

On Sunday night 24 April 1977 – the night before Anzac Day – an episode of the popular television program ‘This is Your Life,’ hosted by Roger Climpson, aired on television. The subject that night was Vivian Bullwinkel, and among the guests were nine of the 24 surviving nurses, including Elizabeth. The others were Jenny Ashton, Veronica Turner (née Clancy), Jess McAuley (née Doyle), Nesta Hoy (née James), Betty Jeffrey, Sylvia McGregor (née Muir), Wilma Young (née Oram) and Ada ‘Mickey’ Syer. Other guests included Ken Brown, who helped to locate the 24 nurses in Sumatra at the end of the war and with Fred Madsen flew them from Lahat to Singapore, and Harry Windsor, a medical officer attached to the 2/14th AGH who travelled with the rescue party and met the nurses on Lahat airstrip.

In memoriam

Jessie Elizabeth Simons Hookway died on 23 December 2004 at the Wynyard Nursing Home in Launceston. She was 93 years old and had led an extraordinary life.

We will remember her.

Sources

- Gill, J. (2010), ‘Sister Jessie Elizabeth Simons: Launceston’s only female prisoner of war,’ Launceston Historical Society Papers & Proceedings.

- Henning, P. (2013), Veils and Tin Hats: Tasmanian Nurses in the Second World War.

- Jeffrey, B. (1954), White Coolies, Angus & Robertson Publishers.

- Libraries Tasmania, Names Index.

- Libraries Tasmania, Tasmanian Post Office Directories.

- Michael McFadyen’s Scuba Diving Website, ‘SS Tekapo – ex SS Cape Clear.’

- National Archives of Australia.

- Simons, J. E. (1954), While History Passed, William Heinemann Ltd.

- Tassell, M. (2000), ‘Rural Launceston Heritage Study: Report of the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, Launceston.’

- WikiTree, ‘Jessie Elizabeth Simons.’

Sources: Newspapers

- The Advocate (Burnie, Tas., 9 Nov 1935, p. 10), ‘West Coast News and Views.’

- The Argus (Melbourne, 28 May 1954, p. 8), ‘Talkabout.’

- The Colonist (Launceston, 28 Dec 1889, p. 22), ‘City School.’

- The Daily Telegraph (Launceston, 29 Aug 1883, p. 2), ‘Shipping.’

- The Daily Telegraph (Launceston, 26 Oct 1883, p. 3), ‘The Immigrants Per Cape Clear.’

- The Daily Telegraph (Launceston, 21 Dec 1889, p. 3), ‘City School.’

- The Examiner (Launceston, 8 Dec 1943, p. 6), ‘Two Tasmanian Nurses Now Prisoners of War.’

- The Examiner (Launceston, 6 Dec 1945, p. 4), ‘Former P.O.W. Sister.’

- The Examiner (Launceston, 22 Jul 1947, p. 5), ‘Need for Interest in Trained Nurses’ Assn.’

- The Examiner (Launceston, 18 Feb 1952, p. 9), ‘Honoured Memory of P.O.W. Sister.’

- the Examiner (21 May 1954, p. 13), ‘Nurse’s Experiences As P.O.W. In New Book.’

- The Launceston Examiner (7 Mar 1896, p. 10), ‘Advertising.’

- The Mercury (Hobart, 7 Sep 1934, p. 6), ‘Meetings Child Welfare Association.’

- The Mercury (Hobart, 29 Oct 1945, p. 7), ‘Tasmanian Nurse Tells of Grim, Harrowing Experience as [Japanese] Captive.’

- North-Eastern Advertiser (Scottsdale, 4 Apr 1924), p. 3), ‘Myrtle Bank.’

- North-Eastern Advertiser (Scottsdale, 12 Sep 1941, p. 3), ‘Wedding Bells.’