AANS │ Staff Nurse │ First World War │ India │ England │ No. 1 AHS Karoola

FAMILY BACKGROUND

Elizabeth Rothery, sometimes known as Lizzie, was born in 1882 in Whitehaven, Cumberland, England. She was the eldest child of Mary Jane Turner (1855–1946) of Whitehaven and Joseph Rothery (1858–1945) of Cleator Moor, near Whitehaven.

Mary and Joseph were married at St. John’s Church in Cleator Moor on 15 January 1882, and later that year Elizabeth was born. On 17 May 1883 the Rotherys departed London on the Macduff bound for Melbourne and arrived on 18 August. In migrating to Australia, Joseph was following his brother John, who in 1876 had sailed to Melbourne from Ipswich on the Zelia.

EUROA

Soon after their arrival, Joseph and Mary settled in the town of Euroa, 150 kilometres northeast of Melbourne, and in December 1883 their second daughter, Hannah Stanley, was born. Joseph entered into public life in Euroa with enthusiasm and in June 1884 was elected to the town’s first ‘parliament’ as ‘minister of justice.’ He also became president of the Euroa Traders’ Association.

Sometime in 1884 a son named Henry was born, but his birth registration cannot be found. Another son, John Norman, was born in 1885.

SOUTH MELBOURNE

Around August 1885, Joseph, Mary and their four children left Euroa and moved to South Melbourne, a working-class inner suburb of Melbourne. On 11 April 1886 John died aged only 9 months. He was the first of six children whom Mary and Joseph Rothery so tragically outlived.

In 1887 a third daughter, Frances Ann May, known as Fanny, was born to the Rotherys, who by March 1888 were living at 43 Park Street in South Melbourne. In November of that year Joseph leased premises at 250 Bridge Road in Richmond that were formerly those of a dealer in china, glass and earthenware. If, as it appears, Joseph continued to trade in these goods, he would of course be dealing with suppliers. One such supplier might have been the Ovens Pottery Company of Hurdle Flat, a locality just south of Beechworth in northeastern Victoria.

It just so happened that in December 1889 Joseph was appointed business manager, secretary and traveller of the Ovens Pottery Company. Apart from pots, the company made such items as bricks, chimney pots, sewerage pipes, garden materials, and even the Excelsior Butter and Milk Refrigerator. The family followed Joseph to Beechworth, relocating from Normanby Road in Caulfield, a southeastern suburb of Melbourne.

BEECHWORTH

Elizabeth was now seven or eight and living once again in country Victoria – whether in Beechworth township or somewhere closer to Hurdle Flat, we do not know. Nor do we know whether she was attending school at this time. We do know, however, that Joseph continued his civic engagement, joining, for example, the Beechworth Mutual Improvement Society.

In Beechworth the Rotherys continued to suffer tragic blows. In 1890 Mary’s and Joseph’s first son, Henry – whose birth remains something of a mystery – died in Beechworth aged 6 years. In 1891 another son, Abraham James, died two days after his birth. In five years the Rotherys had lost three children.

In late May 1895 Mary’s and Joseph’s final child, Henry Norman, known as Norman, was born. Elizabeth was now 12 or 13, Hannah 11 and Fanny seven or eight. One can only imagine how precious they considered their new brother – their only one.

MYRTLEFORD

It was around this time that the Rotherys moved from Beechworth to Myrtleford, a picturesque town 25 kilometres to the south. Joseph had finished his association with the Ovens Pottery Company – which had closed in 1892 due to mounting debts and was in the hands of the liquidators – and was looking for new opportunities.

In Myrtleford Joseph threw himself as always into civic life. He had already joined the committee of the Myrtleford Football Club and now took an interest in the local tobacco growers’ association. In August 1895 he stood for election to the Bright Shire Council but was defeated by 38 votes by his rival.

In July 1896 Joseph was fined for neglecting to have Norman vaccinated. When his case went to court he admitted the offence but stated that he had recently lost a child (Abraham) in Beechworth from the effects of vaccination and did not intend to have this one vaccinated, as he did not believe in it.

In the latter years of the 1890s Joseph became increasingly involved in mining pursuits. Having already acted as an agent for other applicants for mining leases in the district, in April 1897 he applied on his own behalf for a mining lease under the name of Greystone Gold Mining Company and in November of that year he applied for another under the name of The Crown Gold Mining Company. At the same time, he was secretary of the Ovens Valley Deep Lead Prospecting Company and in March 1897 was elected legal manager with fixed remuneration of 10s per week.

SCHOOL AND NURSING

In 1898 Elizabeth attended the sub-matric class at Miss Appleton’s Private School on Balaclava Road in Beechworth. She excelled academically, finishing dux of the school and winning prizes in history and geography at the end-of-year prize day. Whether she was boarding at the school or staying with family in Beechworth for the year is unknown. Elizabeth was nevertheless coming and going between Beechworth and Myrtleford, and on 11 October 1898 she and her sister Hannah were confirmed at St. Paul’s Church of England in Myrtleford.

After her year at Miss Appleton’s, Elizabeth presumably returned to Myrtleford and at some point began to work in her father’s drapery store. While still engaged in mining pursuits, and having also become secretary of the Myrtleford Butter Factory Co. Ltd, by 1903 – and probably earlier – Joseph was running a drapery business on Clyde Street in Myrtleford. It appears to have been the same drapery, grocery, ironmongery and general business that was owned and run by Mr. Thomas Mathieson and put on the market in March 1895.

On 18 June 1906, when Elizabeth or one of her sisters was closing up for the night, the store caught fire after a lantern fell and ignited articles of clothing. Luckily two passers-by rushed in to help and, together with Joseph Rothery and two if not all three of the sisters, extinguished the fire before it could really take hold.

In 1909, when she was 26 or 27, Elizabeth began nurses’ training at Ovens District Hospital (also known as the Beechworth Hospital) under Matron Winning. On 4 June 1912 she passed her Royal Victorian Trained Nurses’ Association (RVTNA) examination and in August obtained her certificate. Finally, on 12 October she became a registered member of the RVTNA.

By 1915 Elizabeth had relocated to Melbourne. During the first half of that year, she trained in midwifery at the Women’s Hospital in Carlton while residing at the Winfield Trained Nurses’ Home at 340 Albert Street in East Melbourne. She completed her training in July and became registered in midwifery on 4 November.

THE GREAT WAR

By then the Great War was raging. More than 200,000 men had enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) for service in Egypt and Gallipoli. Norman Rothery was one of them. On 30 March 1915 he enlisted at Birregurra near Colac and became a private in the 24th Battalion, 6th Infantry Brigade. After embarking for Egypt, he served in the Gallipoli campaign and was killed in action on 29 November at Lone Pine. The Rotherys had lost their fourth son.

Meanwhile, hundreds of Australian women had joined the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS). Many hoped to serve abroad with the AIF but often completed a period of home service first. In 1915 Elizabeth joined too. After attaining her midwifery certificate, she was appointed as a staff nurse to No. 5 Australian General Hospital (AGH) on St Kilda Road in Melbourne, commonly referred to as the Base Hospital.

No. 5 AGH had opened in March 1915 in the newly completed but as yet unoccupied Police Hospital and treated AIF enlistees still in camps around Melbourne as well as those returning from Egypt as invalids. The hospital initially had 40 beds, with one medical officer and eight nurses, but soon expanded dramatically.

Elizabeth was still working at No. 5 AGH in August 1916 when the opportunity arose to sail to India to treat the ill and wounded of the Mesopotamian Expeditionary Force (MEF). The MEF, made up predominantly of British and Indian soldiers, was fighting Ottoman forces in the country now called Iraq. Although there were military hospitals in Basra, in southern Iraq, thousands of soldiers were transported across the Arabian Sea to military hospitals in Bombay.

THE AANS IN INDIA

The first Australian nurses had arrived in India in July 1916. Following the movement of AIF infantry divisions to France in April 1916, more than 100 nurses had become surplus to requirements in Egypt. In May, Australian authorities in Cairo, aware of the need for trained nurses in India, sought permission from the Commonwealth Government to send 50 of the spare nurses to India. On the recommendation of Maj. Gen. Richard Fetherston, the director general of medical services in Australia, the Commonwealth Government cabled India offering the 50 nurses. The Indian Government gratefully accepted, and on 23 July the nurses arrived in Bombay on the Neuralia under Sister Emily Hoadley.

The nurses expected to serve together as a complete staff but instead were split up and posted in groups of three or four or even individually to ‘station’ or garrison hospitals in Calcutta, Lahore, Mooltan (Multan), Naoshera (Naushera), Sialkot, Quetta and elsewhere. At these station hospitals, which were maintained by the Indian Government and usually consisted of 100–150 beds, the Australian nurses treated the sick and injured of the local garrison, which they did not consider to be true war nursing. Some of the nurses remained in Bombay and were posted either to the Gerard Freeman-Thomas Hospital, located 500 metres north of the famous Taj Mahal Hotel, or to the Colaba Military Hospital in southern Bombay. Tragically, two of them, Staff Nurses Amy O’Grady and Kate Power, contracted cholera and died at Colaba Military Hospital in mid-August.

Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. Fetherston had written to the director of medical services in India offering to send additional trained nurses directly from Australia should they be wanted, as plenty were available. His letter crossed a request from the War Office cabled on 26 July and relayed through the High Commissioner that 100 Australian nurses be sent 50 each to India and Malta for Imperial Service. This was agreed to by the Commonwealth with the proviso that the nurses should serve as members of the AANS, retaining their Australian rank and conditions as part of the AIF.

On 7 August, soon after the agreement with the War Office was reached, the Indian Government’s reply to Maj. Gen. Fetherston was received. Fifty nurses should be sent to Bombay as soon as possible, with another 50 to follow a month later. The agreement with the War Office was cancelled.

The mobilisation of the first 50 nurses of the awkwardly named AMC British Indian Service AIF began with a call for volunteers. Perhaps because Maj. Gen. Fetherston was based in Melbourne, 35 nurses of No. 5 AGH puts their hands up. Among them was Elizabeth. She and the others must have relished the opportunity to serve abroad.

RMS MOOLTAN

The 35 nurses boarded the RMS Mooltan at Port Melbourne on 22 August 1916, a date that was later recorded as their date of enlistment in the AIF. They were under the charge of Sister Gertrude Davis, who had previously been a member of staff at No. 5 AGH before serving in Lemnos and Egypt with the 3rd AGH and then returning to duty for this posting. Sister Davis would remain in India for more than two years. Appointed (temporary) principal matron of the AANS nurses in India on 1 January 1917, she would subsequently be mentioned in despatches and awarded the Kaiser-I-Hind Medal and the Royal Red Cross (1st Class).

The Mooltan departed Port Melbourne at around 4.00 pm that afternoon. Aside from the 36 nurses, the ship was carrying several hundred Light Horse troops for Egypt and 270 staff of the 1st Australian Wireless Signal Squadron for Mesopotamia. On 24 August the Mooltan reached Port Adelaide, where nine more nurses embarked. Four days later, following a wild passage through the Bight and around Cape Leeuwin, the ship dropped anchor in Fremantle. Four additional nurses boarded, and later that night the Mooltan set out for Colombo, Ceylon, from where the nurses would transship to Bombay. According to the nominal roll, there were now 49 AANS nurses aboard the Mooltan, not 50, as had been requested by India. Whether someone had been mistakenly left off, and there were in fact 50 aboard, is unknown.

After a pleasant voyage through calm seas, the nurses arrived in Colombo at around 4.30 pm on 6 September. They were charmed by what they saw. “The natives in their tiny Katermarangs [catamarans] dancing about on the water fascinated us – we feared each moment they would swamp & sink,” wrote Sister Alma Bennett in her 1919 report to the Assistant Collator of Medical War History. In a letter that was later printed in the Heidelberg News, Staff Nurse Elsie Deakin stated that the nurses “were glad to reach Colombo, and thought the harbor there beautiful, and it was all so strange to us.”

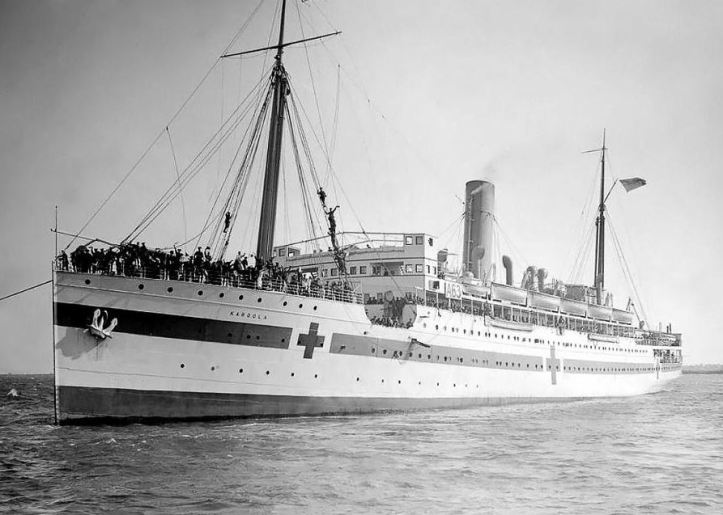

The nurses disembarked and were taken to the Grand Oriental Hotel, whose large, airy rooms delighted them. Here they happened to meet nurses of the 14th AGH, who had been granted 40 hours’ shore leave in Colombo while en route from Australia to Egypt aboard the Australia hospital ship Karoola, on which Elizabeth would one day serve.

At 8.00 pm dinner was served. In her report Alma Bennett recalled “the white clad servants gliding noiselessly round attending to our wants so skilfully and silently. The evening was hot, and how we all enjoyed an iced lime squash. After dinner coffee was served in the lounge, a delightfully cool, comfortable spot, with many graceful palms.” Soon the nurses broke up into groups and, as they were not sailing until the evening of 9 September, made plans for the next three days.

The following morning Elizabeth and the others began to explore the city. They took rickshaw rides through beautiful gardens and ventured farther afield. One group caught the train to Kandy, an attractive town in the centre of the island that was home to the famous Temple of the Tooth. They had a most delightful day.

BOMBAY

At midday on 9 September 1916 the 49 nurses departed Colombo on the Mora, a small steamer operated by the British India Steam Navigation Company. As their vessel pulled away from the harbour, they watched the Mooltan, still at anchor, receding in the distance.

After an uneventful voyage of three days, Elizabeth and her colleagues arrived in Bombay at 10.00 pm on 12 September. At 11.00 am the next morning they boarded a small boat and in the pouring rain landed at Bori Bunder, a prominent port and warehouse precinct, where Victoria Terminus was located. They were then split up among three hospitals around the city – the Colaba War Hospital, the Cumballa War Hospital, and the hospital that had been set up in the Taj Mahal Hotel. It was here that Elizabeth was sent, along with Gertrude Davis, Alma Bennett and others.

Two days later, the nurses posted to the Taj Mahal Hotel were ordered to leave following a death from cholera. They relocated to the Victoria War Hospital, which had been established in May in the newly built headquarters of the Great Indian Peninsular Railway (GIPR), situated next to Victoria Terminus in Bori Bunder. The hospital’s British nurses were in the process of transferring to Mesopotamia, and Gertrude Davis immediately took over from the British matron, who was ill.

The four-storey GIPR building made a splendid hospital. Each of the first three floors was divided into two wards, each ward with 100 beds, while the fourth floor housed the nurses’ quarters. The wards were brightly lit with electric lights and had punkahs (ceiling fans), which were greatly appreciated in the trying heat of Bombay. Each ward was also supplied with hot and cold water.

When the AANS nurses arrived, all 600 beds were occupied. The ill and wounded patients had been transported from aid posts and dressing stations near the Mesopotamian front to the southern city of Basra, and from there in hospital ships via the Persian Gulf and the Arabian Sea to Bombay, a journey of 3,000 kilometres. According to Gertrude Davis’s 1919 report to the Assistant Collator of Medical War History, there were 100 surgical cases, 100 dysentery, 150 enteric (typhoid fever), 50 para-typhoid A and B, 100 mixed medical, and 100 semi-convalescent cases.

Within 10 days the remaining British nurses had departed and many of the AANS nurses who had initially been sent to Colaba and Cumballa hospitals had been transferred to the Victoria Hospital. “My staff,” wrote Sister Davis in her report, “was now 40 A.A.N.S. and 10 nurses, some trained and others untrained, most of them being Eurasians.”

Other duties were carried out by local people – which lead to certain challenges, as Gertrude Davis explained in the language of the day. “The ward work was performed by native servants of different casts [castes],” she wrote, “and the main difficulties with them were to know what their duties were. There were ward boys who did the dusting, washing of lockers and dishes. Bhestis, who carried water to and from the patients. Sweepers, who swept the floors and attended to the latrines. Many were the mistakes made at first and as none of these servants could speak English and the sisters did not know Hindustani, so all communications had to be made by sign and gesture.”

For the next two months Elizabeth and her colleagues had plenty of work to keep them busy, as Sister Davis illustrated in her report. “The work was very heavy as this hospital was the nearest to the docks, which were less than 5 min. away so we got all the most serious cases,” she wrote. “Just one week after our arrival we received 300 released prisoners from Bagdad. When Kut-el-Amara fell to the Turks, Gen. Townsend exchanged able bodied Turkish prisoners of war for his sick and wounded British prisoners held by the Turks. More emaciated from disease and starvation, one would never see. It took three months for them to come from Bagdad to Bombay and although the greater % of them were serious cases of dysentery, beri-beri and old septic wounds, we only lost two men out of the 300.” The British ex-prisoners were unable to eat properly for months afterwards.

Towards the end of the year the Victoria Hospital’s workload lessened considerably, and by December the nurses had only 130 patients under their care. After the fall of Kut-el-Amara, British authorities had introduced sweeping changes to the conduct of the Mesopotamian campaign. The MEF was placed under the command of Gen. Stanley Maude, who proceeded to rebuild and reshape the force and was ordered not to renew the offensive. At the same time, yawning deficiencies in logistical infrastructure were addressed, including improvements in medical facilities – all of which meant fewer patients ending up in Bombay via the medical evacuation chain.

However, in early December Gen. Maude received orders to renew the offensive and on 13 December began to move on Baghdad. Far from having a quiet Christmas, as the nurses had anticipated, by Christmas Day the hospital was full of surgical patients, 80 serious cases having arrived that very morning.

ENGLAND

On 15 January 1917, only three weeks after Christmas, Elizabeth boarded the Mooltan once again and departed Bombay after four months in India. Sister Elsie Deakin and most likely other nurses sailed with her, having completed their Indian service. The Mooltan had arrived at Bombay with a further 50 nurses for the British Indian Service having departed Melbourne on 26 December 1916.

Elizabeth and Elsie arrived in England and on 21 February were posted to the Bagthorpe Military Hospital in Nottinghamshire. The hospital, which had opened in 1914, occupied the buildings of the Bagthorpe Workhouse and Infirmary in Nottingham’s northern fringes. There was at least one other AANS nurse posted there at the time, Staff Nurse Evelyn Hutt from Tasmania. She had previously worked on Lemnos and in Egypt and had been posted to Bagthorpe on 18 January 1917.

Sometime after her posting to Bagthorpe, Elizabeth was transferred to Queen Mary’s Military Hospital in Whalley, Lancashire. Housed in a newly built asylum, Queen Mary’s Military Hospital had officially opened on 14 April 1915 and was one of the largest military hospitals in England.

From Whalley Elizabeth was posted to No. 2 Australian Auxiliary Hospital (AAH) in Southall, west London and arrived on 7 July. No. 2 AAH had been established in August 1916 in the buildings of the St. Marylebone Schools on South Road in Southall. The hospital had originally functioned as a clearing station for the 1st AAH, located at Harefield, 20 kilometres to the north, but in November 1916 had begun to specialise in amputations and prosthetics.

Two days later Elizabeth was attached to No. 1 AAH but returned to No. 2 AAH on 20 July. In two days’ time she was to embark for Australia on transport duty.

On 22 July Elizabeth, Staff Nurse Jessie Mudd, who had served with Elizabeth in India, Sister Rachel Clouston, and others boarded HMAT Nestor and departed for Australia with a complement of invalided AIF soldiers. The ship sailed via Freetown in Sierra Leone and Cape Town in South Africa and on 13 September arrived in Fremantle. The Nestor continued across the Bight to the east coast and on 24 September Elizabeth disembarked in Melbourne.

RETURN TO AUSTRALIA

After returning to Melbourne, Elizabeth visited her parents in Myrtleford. Much had happened during her absence. Tragically, on 2 April 1917, while Elizabeth was at Bagthorpe or Whalley, her sister Fanny had died while living in the town of Merino, near Casterton in western Victoria. She had moved to Merino with her husband, Mr. Osland Kelly, after they were married in 1911. In 1913 or 1914 Joseph and Mary Rothery joined Fanny in Merino and kept a grocery, wine and spirits store. Hannah Rothery meanwhile was living in neighbouring Casterton until shortly before her marriage to the Rev. Thomas Gair in June 1916. After Fanny’s death Joseph sold his business to Osland Kelly and in August 1917 he and Mary returned to Myrtleford.

Even while living in Merino, Joseph was returning periodically to Myrtleford. It would seem that his drapery business on Clyde Street had remained an ongoing concern, possibly under different management, and besides that he retained half-ownership of the Myrtleford Hotel.

On 29 November 1916 a service was held at St. Paul’s in Myrtleford at which Joseph and Mary were surely present. On the anniversary of Norman Rothery’s death a stained-glass window that Joseph had presented to the church in memory of Norman was being dedicated by Dr. Armstrong, Bishop of Wangaratta. The service was an impressive one. Special prayers were recited, and special hymns were sung by the choir, accompanied by Miss. A. O’Donnell on the organ. Miss A. O’Donnell – Alice – was the 15-year-old daughter of Myrtleford locals Sid and Lettie O’Donnell. She grew up to become a nurse, joined the AANS, and in 1943 was one of 11 AANS nurses who lost their lives when the AHS Centaur was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine off the southern Queensland coast.

Sometime after her visit to Myrtleford, Elizabeth was posted to No. 11 AGH in Caulfield, also known as the Caulfield Military Hospital, which had been established in April 1916 at ‘Glen Eira,’ a stately home. Additional wards and buildings were constructed within the grounds of ‘Glen Eira’ to meet growing demand.

In January 1918 Elizabeth was appointed to the nursing staff of HMAHS Karoola under the able charge of Matron Alice Cooper. After being requisitioned in May 1915 and embarking from Australia with troops for the Middle East, the Karoola was converted into a hospital ship in Southampton, England. It then returned to Australia, embarking AIF invalids in Suez en route, and thereafter plied between Australia, Egypt and England, carrying medical staff to England and returning with invalided Australian soldiers. From 1917 voyages to England were made via the Cape and west Africa, as sailing through the Mediterranean had become hazardous due to German U-boat activity.

On 23 January the Karoola departed Melbourne, bound for the Middle East. It steamed across the Indian Ocean to South Africa and then travelled up the east coast of Africa to Suez. After embarking patients, the Karoola returned to Australia.

HER FINAL DAYS

Elizabeth made a second voyage on the Karoola between 23 March and 26 May 1918. She anticipated sailing for a third time on 12 June. It was not to be.

After arriving in Melbourne on 26 May, Elizabeth visited her parents in Myrtleford. She then went to see her friend Sarah Wilson, who lived on Last Street in Beechworth. Sarah became alarmed when Elizabeth very suddenly became ill and summoned Dr. Skinner, who diagnosed severe appendicitis. Then Nurse Clemens, who had trained with Elizabeth, also came to her assistance.

On Tuesday 11 June Elizabeth’s parents were informed of her serious condition and rushed to Beechworth. Her sister, Hannah, also came up from Melbourne. Owing to Elizabeth’s heart condition an operation was impossible, and despite everyone’s very best efforts, early on Saturday morning 15 June the case was seen to be hopeless. To the very last, Elizabeth’s thoughts were with her soldier patients, and she passed away on Saturday afternoon, 15 June 1918.

FUNERAL

On the afternoon of the following day Elizabeth was accorded a military funeral. People crowded the route along which the funeral party processed to Beechworth Cemetery, where many more people waited. When the cortege reached the cemetery Elizabeth’s coffin, wrapped in the Union Jack and adorned with her AANS uniform, was taken from the hearse and placed on the shoulders of six returned soldiers. Other returned soldiers followed behind, along with members of the Rifle Club, the Beechworth Town Band, and others. After the burial service was read by Archdeacon Potter, the Beechworth Town Band played ‘Abide with Me.’ The firing party fired three volleys over the grave and, after being dismissed, marched in single file around the open grave, each member depositing a handful of earth on the coffin as he passed. Then ‘The Last Post’ was sounded.

IN MEMORIAM

On 22 June 1918 there appeared in the Ovens and Murray Advertiser the following tribute Elizabeth:

In Memory of Nurse Rothery

The sombre clouds hang thick and low,

The wintry winds are sighing,

And saddened voices softly tell –

“A noble maid is dying.”

So; through the mist I dimly see

The flags at half-mast flying,

For in the shrouded halls of death

A silent form is lying.

And now behold an open grave

With weeping friends surrounding,

Whilst bugle notes ring on the air,

The last sad tribute sounding.

What though the last sad hour has tolled –

What though the grave is yawning –

To faithful souls that open grave

But indicates the dawning.

Oh mourners cease! On high her deeds

Are faithfully recorded.

Her task well done, and she shall be

Abundantly rewarded.

P. O’REILLY

Several months after Elizabeth’s death, Joseph Rothery planted a Kurrajong seedling in Myrtleford as a living memorial to his eldest daughter. It was replaced in the 1980s with another, which grows to this very day on Clyde Street.

In memory of Elizabeth.

SOURCES

- Alpine Shire, ‘Heritage Citation Report, 18 Jan 2024.’

- Ancestry Library Edition.

- Australian Clay Bottles (website), ‘Ovens Pottery Coy Ltd And H L & E Beechworth Pottery.’

- Australian War Memorial, Australian Imperial Force, Nominal Roll, Nurses, 26/100/1.

- Australian War Memorial, Australian Imperial Force unit war diaries, 1914–18 War, Medical, Dental & Nursing, Australian Army Nursing Service in Egypt, 26/97/1 Part 1.

- Australian War Memorial, Butler Collection, Nurses’ Narratives, Ella McPherson, AWM41 1003.

- Australian War Memorial, Butler Collection, Nurses’ Narratives, Sister Alma L. Bennett, AWM41 942.

- Australian War Memorial, Butler Collection, Nurses’ Narratives, Sister G. E. Davis, AWM41 960.

- BirtwistleWiki (website), 5th Australian General Hospital.

- Burke, E. K. (ed., 1927), With Horse and Morse in Mesopotamia, Arthur McQuitty & Co.

- Butler, A. G. (1943), Official History of the Australian Army Medical Services, 1914–1918, Vol. III – Special Problems and Services, Section III – The Technical Specialties, Chap. XI – The Australian Army Nursing Service (pp. 527–89), Australian War Memorial.

- First World War East Sussex (website), ‘Death of Lord Willingdon’s Son and Heir’ (Rosalind Hodge).

- Goodman, R. (1992, 2016), Hospital Ships, Boolarong Press.

- Hanson, A. (2023), Ovens District Hospital (website), ‘Elizabeth (Lizzie) Rothery 1882–1918.’

- Lancashire Museum Stories (website), ‘Queen Mary’s Military Hospital, Whalley.’

- National Archives of Australia.

- National Library of Australia, ‘No. 5 A.G.H.: a magazine published by the patients and staff of No. 5 Australian General Hospital, St Kilda Road, Melbourne’ (vol. 1, no. 1, 5 Aug 1918).

- Nottingham Hospital History (website), ‘Nottingham City Hospital.’

- Past India (website), ‘Cumballa Hill War Hospital Bombay, 1915 Red Cross Postcard.’

- Public Record Office Victoria, Royal Victorian Trained Nurses’ Association Nurses Register (VPRS 16407/P0001), No. 3, 1,466–2,428, 22 Oct 1910–4 Mar 1915.

- Public Record Office Victoria, Unassisted passenger lists 1852–1923 (VPRS947), May–Aug 1883.

- University of NSW, Canberra, The AIF Project, ‘Elizabeth Rothery.’

- Wikipedia, ‘1st Australian Wireless Signal Squadron.’

- Wikipedia, ‘Mesopotamian campaign.’

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS

- The Age (Melbourne, 4 Jan 1884, p. 1), ‘Advertising.’

- The Age (Melbourne, 14 Mar 1888, p. 3), ‘Advertising.’

- The Age (Melbourne, 25 Sept 1888, p. eight, ‘Advertising’

- The Age (Melbourne, 23 Aug 1895, p. 6), ‘Country Municipalities.’

- The Age (Melbourne, 24 Apr 1937, p. 12), ‘Tablet Unveiled.’

- Alpine Observer and North-Eastern Herald (Vic., 21 Jun 1918, p. 2), ‘Concerning People.’

- The Argus (Melbourne, Vic., 14 Mar 1895, p. 3), ‘Advertising.’

- The Argus (Melbourne, 18 Jun 1918, p. 6), ‘Death of Army Nurse.’

- The Casterton News and the Merino and Sandford Record (Vic., 12 Jul 1915, p. 2), ‘Advertising.’

- The Casterton News and the Merino and Sandford Record (Vic., 2 Aug 1917, p. 3), ‘Merino.’

- The Church of England Messenger for Victoria and Ecclesiastical Gazette for the Diocese of Melbourne (Vic., 1 Mar 1898, p. 37), ‘Confirmations.’

- Euroa Advertiser and Violet Town, Longwood, Avenel, Strathbogie, Balmattum and Miepoll Gazette (Vic., 6 Jun 1884, p. 2), ‘Euroa Parliament.’

- Euroa Advertiser (Vic., 31 Jul 1885, p. 3), ‘Advertising.’

- Hamilton Spectator (Vic., 28 Nov 1916, p. 6), ‘Advertising.’

- Heidelberg News and Greensborough, Eltham and Diamond Creek Chronicle (Vic., 6 Jan 1917, p. 4), ‘A Letter from India.’

- The Herald (Melbourne, Vic., 23 Aug 1883, p. 3), ‘The Ship Macduff.’

- Myrtleford Mail and Whorouly Witness (Vic., 3 Feb 1916, p. 1), ‘Siftings.’

- Myrtleford Mail and Whorouly Witness (Vic., 24 Aug 1916, p. 3), ‘State Schools’ Fund.’

- Myrtleford Mail and Whorouly Witness (Vic., 7 Dec 1916, p. eight), ‘Dedication of Memorial Window.’

- Myrtleford Mail and Whorouly Witness (Vic., 4 Oct 1917, p. 1), ‘Siftings.’

- Myrtleford Mail and Whorouly Witness (Vic., 13 Jun 1918, p. 1) ‘Siftings.’

- Myrtleford Mail and Whorouly Witness (Vic., 10 Oct 1918, p. 6), ‘Advertising.’

- Myrtleford Times and Ovens Valley Advertiser (Vic., 24 Oct 1945, p. 3), ‘Obituary.’

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic., 28 Dec 1889, p. 4), ‘Bogus Banking.’

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic., 11 Jan 1890, p. 6), ‘Advertising.’

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic., 11 Jan 1890, p. 12), ‘After the Holidays.’

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic., 7 Jun 1890, p. 4), ‘Beechworth Mutual Improvement Society.’

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic., 12 May 1894, p. 4), ‘Myrtleford.’

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic., 18 May 1895, p. 2), ‘Myrtleford.’

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic., 22 Jun 1895, p. 13), ‘Myrtleford.’

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic., 18 Jul 1896, p. 2), ‘The Direct Vote.’

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic., 6 Mar 1897, p. 4), ‘Ovens Valley Deep Lead Prospecting Company.’

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic., 24 Apr 1897, p. 2), ‘Advertising.’

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic., 20 Nov 1897, p. eight), ‘Advertising.’

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic., 1 Jan 1898, p. 7), ‘Miss Appleton’s Private School.’

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic., 17 Dec 1898, p. 13), ‘Christmas School Vacation.’

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic., 11 Apr 1903, p. 4), ‘Bright County Court.’

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic., 23 Jan 1904, p. 6), ‘Myrtleford.’

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic., 29 Jul 1905, p. 12), ‘Myrtleford.’

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic., 23 Jun 1906, p. 2), ‘Myrtleford.’

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic., 20 Jul 1912, p. 2), ‘No title.’

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic., 12 Sept 1912, p. 3), ‘Ovens District Hospital.’

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic., 15 Dec 1917, p. 2), ‘Visiting Friends.’

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic., 5 Jun 1918, p. 2), ‘Personal Notes.’

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic., 19 Jun 1918, p. 3), ‘Death of Military Nurse Rothery.’

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic., 19 Jun 1918, p. 4), ‘In Memory of Nurse Rothery.’

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, Vic., 26 Jun 1943, p. 1), ‘Do You Remember?’

- The Sydney Morning Herald (15 Jan 1942, p. 12), ‘Family Notices.’