AANS │ Staff Nurse │ Second World War │ Mandatory Palestine, Libya & Egypt

FAMILY BACKGROUND

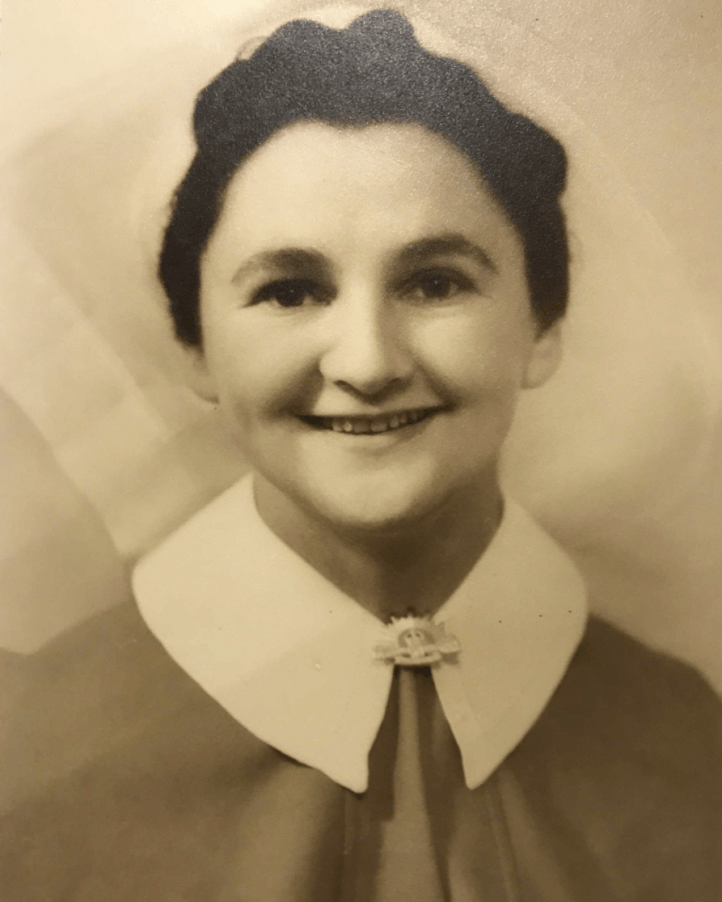

Lilian Elaine McPhail, known as Elaine, was born on 27 January 1909 in Caulfield, Melbourne. She was the daughter of Eva Georgina Jones (c. 1882–1970) and Frederick Charles McPhail (1880–1945).

Eva was born in Sydney and was the daughter of Ernest H. Jones, of Toorak, Melbourne. Frederick was born in St Kilda, Melbourne. He was educated at South Melbourne College, where he was dux, and in 1897 joined the staff of the Colonial Mutual Life Assurance Society. In 1905 he was appointed assistant actuary, and on 27 December of that year he married Eva at St. Martin’s Church in Hawksburn.

Eva and Frederick lived in the eastern suburbs of Melbourne and had four children. Their eldest, Ernest Frederic, known as Eric, was born in 1907. He was followed by Elaine in 1909, Eva Marie Valerie, known as Val, in 1913, and Ian Bruce in 1916. While Frederick pursued his career as an actuary and spent time at his masonic lodge, Eva interested herself in the City of Camberwell Women’s and Queen Victoria Hospitals Auxiliary, which organised social events to raise funds for the two Melbourne hospitals. By 1926 Eva was president of the Mont Albert and Surrey Hills branch of the auxiliary.

EARLY LIFE

Elaine was a bright and cheerful child and had a gift of conveying that cheerfulness to others. She played the pianoforte and in May 1922 took part in an ANA competition held at the Atheneum Hall in Melbourne. She attended Fintona Presbyterian Girls’ Grammar School in Camberwell and in February 1926 passed her school leaving examination, qualifying thereby for her leaving certificate. By this time the family was living at 10 Zetland Road in Mont Albert.

As a young adult, Elaine was involved in the Younger Set of the City of Camberwell Women’s and Queen Victoria Hospitals Auxiliary and helped to organise such events as theatrical performances, tennis tournaments, dances and bridge parties to raise funds for the hospitals. By 1931 she had become honorary treasurer of the Younger Set and in 1933 became president. That year the Younger Set voted to become an independent auxiliary working solely for the Queen Victoria Hospital and changed its name to the Charity Chums. Its first event under the new name was a Derby Whist Night held on 11 November at Elaine’s family home in Mont Albert.

Elaine was also a member of the Milverton Dramatic Club and the Mont Albert Girls’ Branch of the Australian Women’s National League.

NURSING AND ENLISTMENT

Perhaps inspired by her mother’s and her own fundraising work for the Women’s and Queen Victoria Hospitals, Elaine decided to become a nurse and began to train at the Royal Melbourne Hospital around 1935. She passed her final examination in March 1938, graduated in May, and on 1 July 1938 became a registered nurse. She then worked (or trained) at the Infectious Diseases Hospital in Fairfield and was training in midwifery at the Women’s Hospital in Carlton when called to Puckapunyal Army Camp in June 1940.

After joining the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) in February 1940, Elaine had been mobilised as a staff nurse and had now been named among 35 Victorian nurses chosen for service with the 2/4th Australian General Hospital (AGH) under Matron Gwladys Thomas. The 2/4th AGH was a medical unit of the 7th Division, 2nd AIF and was formed on 28 May at Puckapunyal Army Camp, 100 kilometres north of Melbourne. Dr. Norman Lennox Speirs, a well-known Melbourne gynaecological surgeon, had been appointed commanding officer of the unit at the rank of colonel and was now in the process of recruiting medical and administrative staff. Elaine and the other nurses had been chosen from among hundreds of applications considered by the matron in chief of the AANS, Grace Wilson, and the principal matron of Southern Command (Victoria), Gwladys Parker Field.

Elaine arrived at Puckapunyal on 15 June and began working at the camp hospital. On 31 July she was detached to the camp dressing station at nearby Seymour Army Camp and remained there until embarking for the Middle East in September.

THE MIDDLE EAST

In September 1940, while Italian forces were invading western Egypt from Cyrenaica, eastern Libya, 16 nurses of the 2/4th AGH were chosen for service abroad prior to the general embarkation of their unit. Among them was Elaine. The 16 embarked for Egypt with convoy US5 in four groups. On 14 September a group under Sister Madge Brown departed Sydney aboard the Slamat, while on 15 September contingents under Sisters Nell Bryant and Marjorie Hampton departed Melbourne aboard the Christiaan Huygens and Nieuw Holland respectively. Elaine was with Nell Bryant. When the convoy arrived in Fremantle, at least one other 2/4th AGH nurse, Staff Nurse Victoria Hobbs, boarded the Indrapoera, which had left Sydney with the Slamat.

The convoy departed Fremantle on 22 September and, sailing under various escort ships via Colombo and Aden, arrived at Port Tewfik, the port of Suez, on 12 October. The convoy then continued through the Suez Canal, calling at Port Said, and on 17 October reached Haifa in Mandatory Palestine. (Another source suggests that only the Slamat and Indrapoera continued to Haifa, which would mean that the nurses aboard the Christiaan Huygens and Nieuw Holland must have transhipped at Port Tewfik or even at Colombo.) The following day the 16 nurses disembarked and entrained for Gaza Ridge, Mandatory Palestine. Here, on 18 October, they were attached to the 2/2nd AGH.

The 2/2nd AGH had arrived at Gaza Ridge in May 1940 after sailing to Egypt on the Strathaird with units of the 6th Division, 2nd AIF. While a decision was made where to locate its permanent hospital, the unit set up an interim tented hospital close to that of the 2/1st AGH, which had arrived in Mandatory Palestine in February 1940 but had only opened its hospital in April. In the meantime, there was not very much for the nurses of the 2/2nd AGH to do, and they were detached to the 2/1st AGH and to various British hospitals, including the 5th British General Hospital in Alexandria, Egypt.

As the end of the year approached, a permanent site was chosen for the 2/2nd AGH on the eastern side of Kantara, a town in Egypt straddling the Suez Canal between Ismailia and Port Said. On 15 December the unit relocated to its new hospital, which had been set up entirely under canvas. On 29 December the 2/2nd AGH began to take patients and by 6 January 1941 the unit was receiving convoys of men wounded in the counteroffensive against Italian forces in western Egypt. Thereafter, the convoys arrived regularly.

ELAINE’S BROTHER AND BROTHER-IN-LAW ARRIVE IN MANDATORY PALESTINE

Meanwhile, Elaine’s brother and brother-in-law had arrived in the Middle East. After he enlisted in the 2nd AIF on 22 May 1940, Ian McPhail was attached to the 2/5th Field Ambulance (FA) as a driver. On 21 October his unit embarked for Egypt aboard the troopship Mauritania, which sailed in convoy with the Aquitania and other ships. After transshipping at Bombay, the 2/5th FA arrived at Kantara on 25 November and from there proceeded to its camp at Julis in Mandatory Palestine, north of Gaza Ridge and east of the ruins of the ancient city of Ascalon.

Arriving at Julis camp on the same day as Ian was Alex Welsh Thomson, Ian’s and Elaine’s brother-in-law, who had married their sister Val earlier in 1940. He was with the 2/14th Battalion and had sailed on the Aquitania and then transshipped at Bombay. By early December, Ian and Alex were both just a few kilometres north of Elaine.

On New Year’s Day 1941 Elaine, Ian and Alex went for a picnic among the ruins of Ascalon and found what they thought was an urn, covered in dirt and almost unrecognisable as anything but a lump of clay. They sent it home to Frederick McPhail, with instructions from Elaine that he should disinfect it before handling it. Frederick McPhail soaked it overnight in Phenyle and the next day found that it was a shining grey wine pot with a circular pattern and two small holes in the side. He took it to Alfred Kenyon, the Keeper of Antiquities at the National Museum on Russell Street in Melbourne, who pronounced it in excellent condition and dated it to between 1500 and 1700 CE. Frederick offered the pot to the museum.

Ian McPhail was in Tobruk with the 2/5th FA when the city was besieged by Rommel. As we will see, Elaine and the 2/4th AGH nurses were there too but were evacuated just before the siege.

Alex Thomson went on to serve in Syria and New Guinea. Both he and Ian returned home safely.

TOBRUK

Around 12 February Elaine’s 2/4th AGH nursing colleagues under the charge of Matron Thomas arrived at the 2/2nd AGH in Kantara. They had left Melbourne with the male staff of the unit on 29 December 1940 aboard the Mauretania and after transshipping at Colombo had arrived at Port Tewfik on 2 February aboard the Nevasa.

While the nurses were heading to Kantara, the men of the 2/4th AGH had proceeded to Amiriya, near Alexandria on the Mediterranean coast, and from there to Barce, near Benghazi in Cyrenaica, eastern Libya. By then the Allies had pursued the retreating Italian forces into Cyrenaica and had captured Benghazi.

On 22 March Col. Speirs was told that the unit should evacuate eastwards to Tobruk as quickly as possible: Rommel had landed in North Africa with his Afrika Korps and would soon be pushing eastwards. The staff began to pack up the hospital once again and prepare for withdrawal, and patients began to be evacuated to Tobruk. The final move order was issued on 26 March, and over the coming days the 2/4th AGH relocated to Tobruk, leaving a rear party in Barce. At the same time, the 2/2nd Casualty Clearing Station (CCS), which had arrived in Tobruk from Alexandria at the end of January, relocated to Barce to take over the 2/4th AGH’s hospital.

On 27 March, while the two Australian medical units were in the process of exchanging locations, the British hospital ship Dorsetshire arrived in Tobruk Harbour from Alexandria to collect sick and wounded patients. As the ship moved towards the wharves, Allied soldiers out on the rocks cheered and waved, for on board were Elaine and the other nurses of the 2/4th AGH, as well as eight nurses of the 2/2nd CCS. The 2/2nd CCS nurses had been attached to the 2/2nd AGH at Kantara on 5 March after remaining in Alexandria when the male staff of their unit had proceeded to Tobruk at the end of January.

For whatever reason – bad weather, unpreparedness, lack of security – the nurses were left on board the Dorsetshire that night, even as sick and wounded patients began to be embarked. They were landed the following day, 28 March, and taken to an empty hotel named the Albergo, reportedly once occupied by Mussolini. The rooms were beautifully fitted out but small and needed cleaning. Once this was done, Sister Madge Brown, second in charge to Matron Thomas, was put in charge of the nurses’ new home, and rosters were drawn up. Then, while the night-duty nurses stayed at the hotel, the day nurses proceeded to their new hospital, more than a kilometre away.

Upon arriving in Tobruk from Barce, the men of the 2/4th AGH had begun to set up a surgical hospital in the former Italian barracks, which was composed of six long, rectangular buildings, each capable of accommodating 100 beds. This was dubbed the ‘town hospital.’ A tented medical section was set up with the aid of the 2/3rd Field Ambulance and some Italian prisoners of war at a beach site three kilometres away. This became known as the ‘beach hospital.’

When the day nurses arrived at the town hospital they set to work turning the long buildings of the barracks into functional wards. They cleaned away rubbish, cleaned the floors, and set up beds with grey blankets. At the end of the day, they marched back to the Albergo, and the night-duty nurses marched down to the hospital.

Casualties from the renewed fighting in the Western Desert began to arrive even before the hospital was officially open, and patient numbers increased as Rommel’s Afrika Korps advanced eastwards. To keep up with patient numbers, the nurses (who had by now been officially reattached to their respective units) opened further wards. Many of the 2/4th AGH orderlies had not yet arrived from Barce, so the nurses had a lot of extra work to do. They carried heavy loads of food from the kitchen to the wards and swept and swabbed the stone floors. As there was no laundry being done, they soon ran out of bed linen.

Many patients had machine-gun wounds due to Luftwaffe strafing along the coast road between Benghazi and Tobruk. They were brought to the hospital in whatever they were wearing, with their wounds bandaged in field dressings. Since good drinking water was scarce – Italian troops had salted the water supply while withdrawing – sometimes several filthy, battle-stained patients were washed with the same dirty water. The lack of pyjamas and bed linen only added to the patients’ discomfort. The nurses did at least have mountains of compressed dressings, thanks to the former Italian occupants of the barracks.

During the night, blackout was strictly enforced, with blankets nailed to the windows and doors to keep the lights from showing. The nurses worked all through the night admitting convoys with only shaded hurricane lamps to see by.

Before long the hospital was full. The nurses forgot about time off; they worked until they had to sleep and then started again. They ran out of beds, then mattresses, and soon patients were lying on the floors. An extract from Sister Nell Bryant’s diary entry of Saturday 5 April offers an insight into the nurses’ working conditions at that time:

On duty 6.30 pm to find the place v busy & as night went on it got worse 23rd Batt. mach-gunned & patients poured in, theatre going all night. Well patients gave up their beds to the sick ones & went on the floor. By morning all v tired & we had 608 patients War news little better … when I did the round I had to go to air raid shelter as some of the boys stayed there all night (quoted in Bassett, p. 120).

On 6 April, the day after the 2/2nd CCS and the rear party of the 2/4th AGH had evacuated Barce and returned to Tobruk, German forces were only 40 kilometres away. Luftwaffe bombers flew overhead, and air raid sirens sounded frequently. The bed situation in the hospital had become critical, and finally the unit’s quartermaster had to give the nurses the beds that he had been saving. They were straight from Australia and wrapped in miles of paper. The nurses removed just enough of it to allow the beds to be assembled. They were soon filled, and patients were put under them as well.

THE NURSES EVACUATE

At around 5.00 pm on 6 April, the 2/4th AGH and 2/2nd CCS nurses were informed that they were to be evacuated. They left the hospital to return to the Albergo. The nurses’ experience that night and the following day, when they embarked on the Vita, was described years later by Victoria Hobbs (who, it will be recalled, had sailed with convoy US5 on the Indrapoera) in a talk she gave entitled ‘Nursing at Tobruk in the Second World War.’ Part of Victoria’s talk was based on a letter sent in 1943 to the film director Charles Chauvel, who was making a film about the famous ‘Rats’ of Tobruk. The letter presented the testimony of some of the 2/4th AGH nurses as compiled into a narrative by Victoria and her 2/4th AGH colleague Anne Errington. According to Victoria:

After we left the hospital the C.C.S. girls [who were working in the two psychiatric wards] underwent a lot of mental trauma because their patients started to scream and run after them … We were not allowed to tell the patients we were going but they knew I’m sure. We would have preferred to have stayed all night and helped. We were marched down the hill and told that we must go. Barney and Charlie, our two orderlies … had been looking after us and they came down with us. Afterwards we said goodbye to them as they slung their packs on their shoulders and took off up the hill once again to the hospital.

The nurses arrived back at the Albergo in the evening and prepared to evacuate. That night, they slept in their uniforms, ready to leave at any moment. During the night there was a terrific sandstorm, which thwarted the Luftwaffe. In the morning, sand was piled up high inside the quadrangle of the Albergo, almost up to the top of the wall.

The nurses departed that afternoon. Victoria Hobbs continues the story:

We were told we would be taking our kit bags only. In these we placed our most prized possessions. [By] the time we had packed them, none of us could even lift them off the floor. [We] left the Albergo about five p.m. in ambulances to drive to the wharf. [There] were soldiers all about and a large transport full of Italian prisoners sailed just as we drew up. [We] embarked about six p.m. [from] the main jetty [on a] large ocean going naval launch. Our ship [the Vita], a British naval hospital ship with the usual white, green and red markings, was about two miles out, near the entrance to the Tobruk harbour just past the bulk of the sunken Italian battle cruiser the San Georgio. We were all attired in our usual outdoor uniform – grey suit, hat and great coats. We wore our great coats to embark and carried a small brown suitcase apiece. Our respirators, Italian water bottles and steel helmets were slung across our shoulders.

The ship we left on took four hundred odd casualties. They ferried them out in a flat boat in flat barges and the hospital ship’s crew had a cunning sling arrangement for hauling the stretcher cases on board. … We were really crowded and we were asked if we were willing to go on duty. Most of us didn’t bother to change. The first night we had to stay out in the harbour because we were still taking on casualties. … In the morning [of 8 April] we got up and were given something to eat in the mess. [After dark] we got out of the harbour and we came to a standstill because … a chain from a mine got wound round our propeller and we had a diver go down and get us free. However the old Vita got through the mine field and took us on our way to Palestine.

The nurses had left Tobruk under protest, with a deep feeling of injustice. All had said that they were willing to take their chances with the rest of the unit. Upon her return to Australia in August 1942, Madge Brown expressed the nurses’ dismay, as quoted in the Melbourne Argus on 21 August. “We were the most miserable girls you could have seen,” she said. “We wanted to stay in the front line, to nurse the hundreds of sick and wounded. However, authority thought otherwise; hospital orderlies were put in our places, and we sorrowfully packed our kits and marched down to the quay, which was even then a graveyard of ships.”

BACK TO MANDATORY PALESTINE AND EGYPT

Elaine and her colleagues arrived at Haifa on 10 April. That same day, the 2/4th AGH’s hospitals in Tobruk were bombed. At least four staff members died and two were seriously injured. Thirty-two patients were listed as killed or missing. It was a black day for the unit.

From Haifa, the nurses entrained for Gaza Ridge, where they were attached to the 2/1st AGH. In May the nurses were dispersed in groups to other units, including the 2/2nd AGH at Kantara and the newly arrived 2/7th AGH at Rehovot in Mandatory Palestine. Elaine returned to the 2/2nd AGH on 28 May with, among others, Nell Bryant and Matron Thomas, who was appointed matron of the 2/2nd AGH following the promotion of Matron Annie Sage to matron in chief, 2nd AIF (Middle East).

The 2/2nd AGH was as busy as ever. The hospital was in a target area, and there were frequent air raids; walking wounded, who were in a nervous condition as the result of previous bombings, sometimes wandered into the desert during a raid and the sister-in-charge of their ward would then have to go and collect them. The nurses spent a good deal of their time off duty at the YWCA recreation centre in Ismailia, which lay on the western side of the Suez Canal 30 kilometres south of Kantara, but they had no respite from air raids there. The YWCA building was on a corner, and the buildings on the other three corners had all been hit by bombs.

Around this time Matron Thomas began to hold weekly musical evenings for the entertainment of her nurses. Whether musicians and singers came to the hospital, or whether the nurses themselves played and sang – as we have seen, Elaine played the pianoforte when she was younger, and Matron Thomas was an accomplished pianist and singer – we do not know. Perhaps it was a combination of both.

THE FINAL NIGHT

Late on Sunday night 31 August 1941, Elaine, Matron Thomas and Sister Dorice Burgess, from Subiaco in Western Australia, were returning in an army vehicle from Ismailia with three British officers. According to Staff Nurse Nan Whiteside (later Nan Schofield), the nurses had gone to Ismailia to “help to give a concert” – perhaps as part of Matron Thomas’s musical evenings; Nan recalled of Elaine and Dorice that “one sang beautifully.”

Travelling north along the west bank of the canal, the vehicle arrived at Kantara, and the driver had just crossed the bridge to the east bank, where the 2/2nd AGH was located, when an air raid siren sounded. The driver duly turned off the vehicle’s lights, and they crept along in the darkness. Suddenly from the opposite direction came another vehicle, and there was a terrific head-on collision. Elaine and Matron Thomas both sustained critical head injuries and were taken to the 1st British General Hospital (BGH) in Kantara. Dorice and two of the officers were badly injured and were also taken to the 1st BGH. The third officer, possibly the driver, was also critically injured and may have died instantly.

Elaine and Gwladys Thomas both died on 1 September. The following day they were buried at the British Military Cemetery, which was close to the 2/2nd AGH. As the funeral procession passed by the hospital, many of the wounded men – Elaine’s and Gwladys’s patients – left their beds and stood reverently in a spontaneous and genuine show of respect.

Meanwhile, Dorice, who had sustained multiple fractures of her pelvis, forearm and leg, remained at the 1st BGH until 5 September and was then moved to the 2/2nd AGH.

A court of inquiry held at Ismailia on 27 October found that “the collision was directly due to the bad visibility produced by an air raid blackout on a practically moonless night. Neither driver saw the other approaching car. No negligence.”

On 13 November Dorice was classified as permanently unfit for service by a medical board and on 21 November returned to Australia aboard the Dutch hospital ship Oranje, arriving in Perth on 6 December. She was admitted to the 110th Perth Military Hospital (also known as the Hollywood Hospital) and not discharged until April 1942. At one point she was warned that it would be a miracle if she ever walked again, but courage and determination pulled her through. By 1945 she was walking without difficulty and showing little sign of the ordeal through which she had passed.

IN MEMORIAM

On Sunday 7 September 1941 a memorial service for Elaine was held at Holy Trinity Church in Kew. Eva and Frederick McPhail, members of the Returned Army Nurses’ Club, and Matron Grey of the Royal Melbourne Hospital were in attendance. Florence Thomas, the mother of Gwladys Thomas, was also present. Later she attended a memorial service held for Gwladys at Canterbury Methodist Church.

By 1948 the Royal Melbourne Hospital had instituted the Elaine McPhail Memorial Prize for the most proficient 2nd-year nurse.

In memory of Elaine.

SOURCES

- Ancestry Library Edition.

- Australian War Memorial, Keith Murdoch Sound Archive of Australia in the War of 1939–45, (VX8383) Dobson (née Bryant), Ellen May ‘Nell’ (Captain), transcript of oral history recording (1 Oct 1990), interviewer Harry Martin, AWMS00961.

- Bassett, J. (1992), Guns and Brooches: Australian Army Nursing from the Boer War to the Gulf War, Oxford University Press Australia.

- Goodman, R. (1983), A Hospital at War: The 2/4 Australian General Hospital 1940–1945, Boolarong Publications.

- Hobbs, V., ‘Nursing at Tobruk in the Second World War’ (transcription of an oral presentation that was donated to the Battye Library Oral History Program), State Library of Western Australia OH135.

- National Archives of Australia.

- Royal Naval Research Archive, ‘H.M.H.S. Vita.’

- Uboat.net (website), section detailing convoy US 5.

- University of NSW, Canberra, Australians at War Film Archive, Madge Brown, archive number 2595 (transcript of interview 10 October 2008).

- University of NSW, Canberra, Australians at War Film Archive, Margaret Mack, archive number 1062 (transcript of interview 8 Oct 2003).

- University of NSW, Canberra, Australians at War Film Archive, Anna Schofield (Nan), archive number 439 (transcript of interview 6 June 2003).

- Walker, A. S. (1962), Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 5 – Medical, Vol. II – Middle East and Far East, Part I, Chap. 5 – Preparations in the Middle East, 1940 (pp. 86–115), Australian War Memorial.

- Walker, A. S. (1962), Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 5 – Medical, Vol. II – Middle East and Far East, Part I, Chap. 7 – Bardia and Tobruk (pp. 124–156), Australian War Memorial.

- Walker, A. S. (1961), Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 5 – Medical, Vol. IV – Medical Services of the Royal Australian Navy and Royal Australian Air Force with a section on women in the Army Medical Services, Part III – Women in the Army Medical Services, Chap. 36 – The Australian Army Nursing Service (pp. 428–76), Australian War Memorial.

- Wikipedia, ‘SS Slamat,’ citing Arnold Hague, Ship Movements, ‘Slamat,’ Don Kindell, ConvoyWeb.

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS

- The Age (Melbourne, 17 Feb 1906, p. 5), ‘Family Notices.’

- The Age (Melbourne, 30 Mar 1926, p. 12), ‘March Supplementary Annual Examination, 1926.’

- The Argus (Melbourne, 6 Sept 1941, p. 5), ‘Army Staff Nurse Killed.’

- The Argus (Melbourne, 21 Aug 1942, p. 5), ‘Nurse Sorry to Have Left Tobruk.’

- The Argus (Melbourne, 13 Dec 1948, p. 8), ‘Nursing Prizes Awarded.’

- Box Hill Reporter (Vic., 31 May 1929, p. 6), ‘Mont Albert.’

- Box Hill Reporter (Vic., 20 Sept 1929, p. 2), ‘Tennis Tournament for Hospital Appeal.’

- Box Hill Reporter (Vic., 29 Nov 1929, p. 8), ‘Surrey Hills.’

- The Herald (Melbourne, 14 Dec 1928, p. 12), ‘Woman’s World.’

- The Herald (Melbourne, 26 Jun 1931, p. 14), ‘Rushing the Spring.’

- The Herald (Melbourne, 25 Sept 1933, p. 14), ‘Clubs Formed: Younger Set Auxiliary.’

- The Herald (Melbourne, 3 Nov 1933, p. 18), ‘Pretty Things.’

- The Herald (Melbourne, 25 Aug 1934, p. 23), ‘Bridge for Charity Chums.’

- The Herald (Melbourne, 6 Jun 1940, p. 8), ‘Victorian Nurses to Go Abroad with 2nd A.I.F.’

- The Herald (Melbourne, 11 Jul 1941, p. 3), ‘Soldiers Unearth Rare Find.’

- Mirror (Perth, 27 Jan 1945, p. 4), ‘Perth War Nurse Had to Learn to Walk Again.’

- Mirror (Perth, 27 Jan 1945, p. 4), ‘One of First Sisters to Go Overseas.’

- Sun News-Pictorial (Melbourne, 6 Nov 1945, p. 8), ‘Mr. F. C. McPhail of Kew, Dead.’

- Table Talk (Melbourne, 19 Nov 1931, p. 47), ‘At Camberwell Town Hall.’

- Table Talk (Melbourne, 7 Apr 1932, p. 32), ‘Tennis Tournament at Camberwell.’

- The West Australian (Perth, 16 Feb 1942, p. 7), ‘Social News.’