AANS │ Sister Group 1 │ Second World War │ Malaya │ 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station

EARLY LIFE

Elaine Lenore Balfour Ogilvy was born on 11 January 1912 in Renmark, a town in South Australia’s Riverland. She was the daughter of Jane Keyes (1881–1962) and Harry Lort Spencer Balfour Ogilvy (1876–1945). Jane was born in Adelaide and became a teacher at Renmark School. Harry, later Maj. Balfour Ogilvy MBE, was a wealthy grazier, landowner and businessman. He was born in Ireland and served with great distinction in the Second Boer War and later in the First World War. Jane and Harry were married on 4 March 1905 at St. Bartholomew’s Church in Norwood, Adelaide.

Elaine, known as ‘Lainie’ within her family and among friends, was the fourth of five children. Her elder siblings were Audrey Airlie (b. 1906), Edith Griselda, known as Zelda (b. 1907) and Francis Herbert Spencer (b. 1910), and her younger brother was Douglas Dunbar (b. 1913).

Elaine grew up in ‘Tannadice’, the family residence in Renmark built by her father in the same year that Elaine was born. The grand house was one of Renmark‘s most notable family homes and the Balfour Ogilvys, greatly admired and respected in the district, were generous hosts.

SCHOOL

Until the end of 1924 Elaine attended the Church of England Grammar School in Renmark. She was a popular and clever girl and excelled in a variety of fields. In 1923, as a Grade 6 pupil, she was awarded the end-of-year class prize with a score of 86 and was also awarded a sewing prize. When the brand-new Renmark High School opened on 11 February 1925, Elaine, now 13, was among the first intake of pupils. In March she qualified for the Renmark Motel academic scholarship, valued at £10 per annum for two years.

In August that year Elaine wrote a letter to Mopoke, the editor of the children’s pages of the Murray Pioneer and Australian River Record. The charming letter bespeaks a bright and confident young person who loves her school and enjoys her sport:

‘Tannadice’, Renmark, Aug 17.

Dear Mopoke. – Will you let me be a member of this club? I love reading the letters, and I think ‘Six Warrigals on the Murray’ is getting very exciting. I wonder how Minty will feel when he wakes up.

I have such a pretty little garden, with pansies all along the front, and then a row of poppies with a break in the middle, and then there is a verbena. It is a pretty blue colour with white in the centre. Behind the poppies I have some delphiniums and then larkspurs. At the very back against the wall there are some red and pink sweet peas. In amongst the pansies there are some yellow and white freesias, and they are nearly out. I have some lovely pansies out and two or three poppies.

We are getting back the results of our terminal exams now and we have only got two more to get out of ten. I go to the high school and I love it there. We all like our teacher very much. She’s such a sport and she coaches us in hockey and plays for another team. For the last fortnight we have been playing real matches, and on Saturday we played the final against ‘Willpra’ the ‘grown-up team,’ and we won. I must now run away, and do my home work. From your affectionate ‘going to be’ clubmate,

Elaine Ogilvy

P.S. – As you insist on knowing our ages, mine is 13½ years.

In October, the talented 13-year-old won four prizes at the Renmark Spring Show. In the ‘Student Children’s Work (Higher Primary Scholars)’ section she won two seconds and a first, in the ‘Small Handwriting’, ‘Set of Maps of Australian States’ and ‘Completed Daybook’ categories respectively; and she won second prize with her canine entry in the ‘Any Other Breed’ class of the ‘Cats and Dogs etc’ section.

In April 1926 Elaine represented Renmark High School in tennis. Playing against her old school, the Grammar School, she lost two closely fought singles matches, but the high school won the tournament. That year she also demonstrated a flair for acting, giving a creditable performance as a shepherdess at the annual school concert held in November in front of 500 people.

In December 1926 Elaine qualified for her Intermediate Certificate, having scored a B Pass in the end-of-year examination. Her subjects were English, Latin, History, Arithmetic, Mathematics 1, Mathematics 2 and Physics. She was also awarded a prize by the high school for two years’ regular attendance, during which period she did not miss a single day – testament to her dedication and conscientiousness.

At the end of 1927, Elaine gained her Leaving Certificate. She had taken English, History, Economics, Maths 2 and Physics. When the head teacher, Mr Johncock, presented his annual report on 27 December, he thanked her and the other prefects for their able help during the year. The occasion marked the end of Elaine’s high school years.

In 1928 Elaine moved to Adelaide to board at Woodlands Church of England Girls’ Grammar School (now St Peter’s Woodlands Grammar School) in Glenelg. During her two years at Woodlands, she regularly travelled back to Renmark for holidays. At one point, in June 1928, she returned to Adelaide by plane – possibly on the brand new De Havilland 61 service introduced only three months earlier.

Woodlands provided many opportunities for Elaine to engage in sporting and other activities. She excelled at swimming and played tennis and hockey, representing the school in the latter, and joined the debating and drama clubs. It was also at Woodlands that Elaine’s passion for singing blossomed.

Elaine had a beautiful singing voice. At the end of 1928 she was awarded a prize in music practice and by the end of 1929 had been invited to join the Adelaide Choral Society. Later, she became involved in the Adelaide Women’s Choir (and in December 1935 succeeded Miss Bertha James as the secretary of the choir).

NURSING

In early 1930, having finished school, Elaine moved back to Renmark and later that year followed her sister Audrey into nursing. On 15 November she hitched a ride to Adelaide with the Rev. T. Thornton Reed, who was engaged to Audrey, to begin her training at the Adelaide Children’s Hospital. Audrey was six years older than Elaine and had recently completed her training at the Children’s.

Elaine was a popular trainee at the Children’s. As always, she loved parties and singing, and over the course of her training engaged in many social activities with colleagues and friends. Nonetheless diligent, she passed her final examination in November 1933 and stayed on at the hospital as a staff nurse. At the end of 1934 she was awarded the hospital’s silver medal.

From 1935 until her enlistment towards the end of 1940, Elaine’s life continued along the same happy track. She continued to work in Adelaide, returned regularly to Renmark, and maintained her busy social life. On 12 July 1938, Elaine’s brother Douglas married Miss Beryl Tucker. Elaine drove up from Adelaide to Renmark for the occasion, returning later that day by plane.

ENLISTMENT

In 1940, with war raging once again in Europe, Elaine decided to volunteer for service, joining her brothers, Spencer and Douglas, in so doing. She applied to join the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) and, having been accepted, was called in to the Keswick Army Barracks in Adelaide on 13 September to enlist in the Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF).

On 8 November Elaine was appointed to the 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station (CCS) as a staff nurse. The 2/4th CCS was being raised under the command of Lt. Colonel Tom Hamilton and was destined for service in Malaya, where war with Japan was anticipated. It would be the closest Australian medical unit with surgical facilities to the front line and would care for casualties until such time as they could be evacuated by ambulance train to a military hospital. In view of this, surgical experience would be a key requisite for many of the unit’s staff, and several of the eight AANS nurses who would eventually join were theatre nurses.

At this stage Elaine had no inkling of any of this, and on 25 November was posted to the hospital at Woodside Army Camp in the Adelaide Hills. Here she made the acquaintance of fellow 2/4th CCS appointees Staff Nurse Millie Dorsch and Sisters Irene Drummond and Mavis Hannah (Irene the more senior). Millie and Mavis were from Adelaide (although Mavis was born in Perth), while Irene was born in Sydney and raised in Adelaide and Broken Hill.

Elaine signed her attestation form on 29 November, thereby finalising her enlistment in the 2nd AIF, and on 9 January 1941 was called up for duty with the 2/4th CCS alongside Millie, Irene and Mavis.

A week later, the four nurses were granted pre-embarkation leave. Elaine returned to Renmark and on 20 January was a guest of honour at a function celebrating four local members of the defence forces. Elaine was feted as the first army nurse from the district, while her brother Douglas was commended for his recent appointment as a Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE) for military gallantry.

On 23 January Elaine, Millie, Irene and Mavis were among a group of 20 or so AANS nurses and physiotherapists being farewelled prior to their departure for overseas at a morning tea hosted by the Commercial Travellers’ Club of Adelaide. Most of the nurses were set for service in the Middle East.

On 30 January, back from leave, the four colleagues entrained for Melbourne, where they met two more 2/4th CCS nurses, Staff Nurses Shirley Gardam and Wilhelmina ‘Mina’ Raymont. Shirley, from Launceston, and Mina, originally from Adelaide, had sailed from Tasmania on 25 January with other elements of the unit.

The QUEEN MARY

On 1 February the six nurses entrained for Sydney. Two days later they travelled to Darling Harbour and were taken by ferry to Bradley’s Point, where the famous passenger liner turned troopship Queen Mary was in the process of embarking approximately 5,850 personnel of the 22nd Brigade, 8th Division, known as ‘Elbow Force.’

Elbow Force was sailing to Malaya – although the troops did not yet know this – where it would join British and Indian formations in garrisoning the British colonial possession against expected Japanese aggression. Travelling with Elbow Force were several medical units, principally the 2/10th Australian General Hospital (AGH), 2/9th Field Ambulance – and the 2/4th CCS.

A second ship was embarking Australian soldiers in Sydney Harbour that day – the Aquitania. That venerable craft was set to carry around 3,300 troops to Bombay, where they would transship for the Middle East. A third ship, the Niew Amsterdam, was due to arrive later that day from Wellington with around 3,800 New Zealand troops. They too would transship at Bombay for the Middle East. The Queen Mary, the Aquitania and the Niew Amsterdam would depart together the following day and sail in convoy.

Elaine and her colleagues joined the scrum and boarded the Queen Mary. After finding their cabins, meeting their 43 peers from the 2/10th AGH, and otherwise getting organised, the 2/4th CCS nurses proceeded to establish a dressing station on the sixteenth deck, where they would treat the troops’ minor injuries and ailments. More serious cases would be sent to the 2/10th AGH, which had set up an operating theatre and a ward.

On 4 February, a beautiful blue day, the Queen Mary was ready to leave. The troops had completed their embarkation, and countless crates of equipment and supplies had been loaded – some marked ‘Elbow Force, Singapore,’ which somewhat undermined the secrecy surrounding the ship’s destination. In the early afternoon, to the cheers of thousands of well-wishers on land and in boats, the Queen Mary, the Aquitania and the Niew Amsterdam set off under the escort of HMAS Hobart.

The convoy was joined by a fourth troopship, the Mauretania, in the Great Australian Bight and on 10 February arrived at Fremantle. When Staff Nurses Peggy Farmaner and Bessie Wilmott boarded the Queen Mary, the 2/4th CCS’s nursing complement was complete. The departure of the ships from Fremantle two days later marked the last time that Elaine and six of her 2/4th CCS colleagues would see Australia. Only Mavis would one day return.

Most of the troops aboard the Queen Mary, and most of the nurses, assumed that they were destined for the Middle East, like their fellows on the other ships. When they finally learned a day out from Fremantle that they were in fact bound for Malaya, many were unhappy at the thought of joining British and Indian troops in mere garrison duty. They thought they would not see action. No one could have guessed how wrong they would prove to be.

When not working shifts at their dressing station, there was plenty for Elaine and the other nurses to do. They played deck tennis and went swimming in the pool, went to the cinema (where, among other films, ‘Diamond Jim,’ a 1935 biopic, was showing), and attended concerts, dances, cocktail parties and cabaret evenings – at some of which Elaine sang. There were also drills and lectures on tropical nursing.

PORT DICKSON

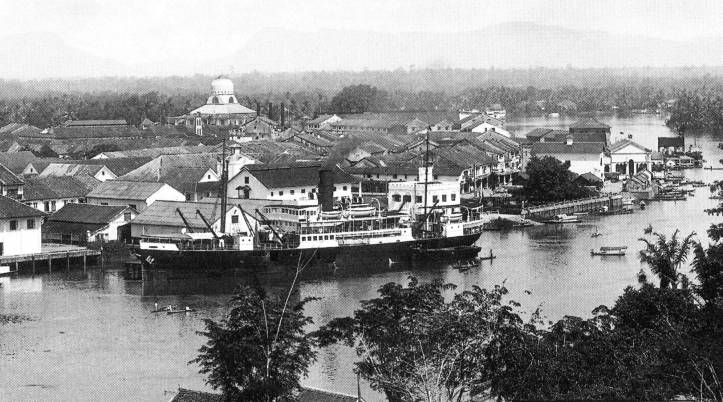

On 16 February the Queen Mary broke away from the other ships and steamed off towards Singapore Island. Two days later, Elaine and the others arrived at Sembawang Naval Base on the island’s north coast, just across Johor Strait from the Malay Peninsula.

The nurses disembarked and were taken to adjacent railway sidings. They gave their names and addresses, were issued with rations, and then entrained for the Malay Peninsula. The 2/10th AGH nurses alighted at Tampin, from where they were driven to the Colonial Service Hospital in Malacca. The 2/4th CCS nurses, apart from Mina, were not yet required by their unit and had been detached to the 2/9th Field Ambulance. They alighted at Seremban, further up the line from Tampin, and were driven to Port Dickson, where the 2/9th Field Ambulance would be based. The other staff of the 2/4th CCS continued to Kuala Lumpur and subsequently moved south to Kajang, where they established a hospital in a high school. After a week at Kajang, Mina joined her AANS colleagues at Port Dickson.

At Port Dickson the 2/4th CCS nurses helped to establish a 50-bed dressing station for the 22nd Brigade troops, whose three battalions, the 2/18th, 2/19th and 2/20th, were based at different camps within the Port Dickson–Seremban area. The dressing station served as a first-aid post, where brigade personnel could receive attention in the event of minor injury or tropical ailment. In more serious cases, they would be transported to the 2/4th CCS at Kajang or the 2/10th AGH at Malacca.

Soon after her arrival, Elaine wrote home to her parents, as reported in the Murray Pioneer and Australian River Record on 13 March. She told them that she was stationed “somewhere in Malaya” and quartered with seven other staff nurses, all of whom were struggling with the Malayan language. The nurses had been supplied with Chinese cooks and “house boys” and were enjoying themselves as much as was possible under the circumstances. They found plenty to do, and were very keen in their work and did not mind long hours and the many discomforts which invariably go with active service conditions.

On 19 July, after five months at Port Dickson, Elaine, Irene and Mina rejoined the 2/4th CCS at Kajang. Millie and Shirley had already rejoined on 7 May and Mavis on 4 June. Bessie and Peggy stayed at Port Dickson until 20 August, shortly before the redeployment of the 22nd Brigade to the east coast of the Malay Peninsula.

SINGAPORE

Elaine, Mavis, Mina and Bessie were granted leave from 11–16 September and travelled to Singapore Island. The famous city on the island was a favoured destination of the AANS nurses. They visited Raffles, sometimes accompanied by officers and sometimes as guests of well-connected locals. They were given privileged access to the exclusive Singapore Swimming Club, with its many facilities. They visited the Singapore Botanic Gardens, with their resident monkeys, and the beautiful Chinese Garden. They were taken out to dinner by officers, followed by dancing or a cabaret, and went on drives. Sometimes they simply went to the cinema. And, of course, the shopping was marvellous.

On 15 September, while Elaine and the others were still on Singapore Island, another Australian general hospital arrived on the island aboard the Australian hospital ship Wanganella. The 2/13th AGH had been raised in Melbourne in August at the request of Colonel Alfred P. Derham, Assistant Director of Medical Services, 8th Division, following intelligence reports suggesting the possibility of a Japanese invasion of Singapore Island from the north. The unit’s arrival came a month after that of the 27th Brigade, 8th Division on 15 August. Travelling with the brigade were 2/10th AGH reinforcement nurses Beth Cuthbertson, Clarice Halligan, Jean Russell, Florence Salmon and Ada Syer.

The 2/13th AGH had a staff of 49 AANS nurses and around 175 officers and other ranks and was billeted at St. Patrick’s School in Katong, on the south coast of the island, pending the readiness of its permanent base, a psychiatric hospital in Tampoi, in southern Johor State on the Malay Peninsula. In the meantime, its nursing staff and orderlies spent time on detachment to the 2/10th AGH and to the 2/4th CCS.

On 19 September Irene Drummond, who had been promoted to the rank of matron on 5 August, was reassigned to the newly arrived 2/13th AGH to take charge of the nursing staff. The following day Matron Drummond was replaced as sister in charge of the 2/4th CCS nurses by Sister Kathleen Kinsella, from Melbourne, who had arrived on the Wanganella with the 2/13th AGH.

ON THE MOVE

By 1 October the 2/4th CCS itself had moved into the psychiatric hospital in Tampoi earmarked for the 2/13th AGH and established a small general hospital of 145 beds. The rambling, single-story complex had been leased from the Sultan of Johor and was ringed around by a high iron fence. It also abutted jungle, and as a consequence it was not unusual for scorpions, centipedes and other creatures to invade the wards. In accordance with the terms of the lease agreement, the psychiatric patients were able to remain on site in a separate building.

November was a month of transition for Elaine’s unit. On 12 November Peggy Farmaner, Mavis Hannah, Mina Raymont and Bessie Wilmott were detached to the camp rest station (CRS) at Segamat, while on 14 November Elaine, Millie Dorsch, Shirley Gardam and Kath Kinsella were detached to the CRS at Batu Pahat, where the 2/30th Battalion was based. In their absence, nursing duties at Tampoi were taken over by 2/13th AGH nurses on detachment. A week later the entire 2/4th CCS relocated from Tampoi to a site in Kluang, in order to be closer to the various 8th Division battalions. An advance party travelled north on 20 November and established the unit’s new base next to a civilian hospital on the edge of Kluang’s aerodrome, with the bulk of the unit arriving three days later. Meanwhile, the 2/13th AGH relocated to the psychiatric hospital. Over the weekend of 21–23 November the unit moved 100 tons of equipment from Katong to Tampoi in an impressive feat of logistics. The 2/13th AGH nurses on detachment to the 2/4th CCS, who had remained at Tampoi, rejoined their unit.

While stationed at Batu Pahat, Elaine fell on uneven ground while stepping over a waterpipe and fractured her left fibula. It was Saturday 22 November, and the 2/30th Battalion had been celebrating its first anniversary; the day’s events culminated in a dinner followed by a concert. Elaine was on duty at the time of her accident and no blame was apportioned to her.

With Japanese troops now massing in French Indochina, all the signs pointed to war. On 1 December the codeword ‘Seaview’ was issued, advancing all Commonwealth forces in Malaya to the second degree of readiness. All leave was cancelled and units had to be ready to move at a few hours’ notice to their war stations. On 6 December Mavis, Peggy, Mina and Bessie arrived at Kluang from Segamat with Major Ted Fisher, one of the 2/4th CCS’s physicians. Later that day the codeword ‘Raffles’ was given, indicating advancement to the first degree of readiness. War was imminent.

War

Little more than a day later it came. At around 12.30 am on 8 December troops from Japan’s 25th Army made coordinated amphibious landings at Kota Bharu on the northeastern Malaya coast and at Pattani and Singora (Songkhla) in Thailand. At Kota Bharu Indian defenders put up stiff but ultimately futile resistance but the landings in Thailand were unopposed, and soon all three attack groups had established beachheads. At around 4.30 am 17 Japanese bombers, flying from southern Indochina, attacked targets on Singapore Island, including air bases at Tengah and Seletar in the north of the island. Raffles Place in Singapore city was also hit, killing 61 people and injuring hundreds, mainly soldiers. Elsewhere, Pearl Harbour, Guam, Midway, Wake Island and American installations in the Philippines were attacked and Hong Kong was invaded. Japan declared war on the United States, Great Britain, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa. The Pacific War had begun.

Elaine, Kath, Millie and Shirley arrived at Kluang from Batu Pahat on the morning of the invasion to find the staff busy making preparations to relocate to the unit’s war station at Mengkibol Estate, a rubber plantation five kilometres to the west of Kluang whose owners were away in India. In anticipation of Japanese hostilities, the site had been earmarked by Lt. Colonel Hamilton some days earlier.

That evening Elaine and her seven colleagues arrived at Mengkibol with “their Chinese amahs, chickens, cook-boy and assistant” and were assigned quarters in a comfortable, two-storey brick bungalow (Hamilton, p. 13). In the days that followed, they helped to set up a casualty clearing station of more than 80 tents under the cover of long avenues of rubber trees. A central road dubbed ‘Kinsella Avenue’ in honour of Kath divided the surgical section from the medical and resuscitation tents. Above the rubber trees flew squadrons of Japanese bombers seeking out Kluang’s railways and aerodrome.

Meanwhile, from their beachheads at Kota Bharu, Pattani and Singora, the well-trained, combat-ready Japanese troops, backed by mechanized units and substantial sea and air power, began to press southwards. Over the coming weeks Japanese soldiers surged down the Malay Peninsula in three prongs at a steady pace of 15 kilometres a day, forcing severely outgunned British and Indian troops to retreat before them. The illusion that had held for so long – that Malaya was well defended – was shattered.

Christmas Day arrived at Mengkibol and provided a welcome diversion from the worsening situation. Comfort Fund parcels (and beer) were distributed in the morning, and at 1.00 pm everyone free of routine duties sat down for an excellent dinner of pork and poultry. Elaine and the other nurses had gathered frangipani flowers and orchids from the bungalow garden and had decorated the tables.

EVACUATION

By 29 December it had become clear that the 2/10th AGH at Malacca would have to be evacuated southwards. Colonel Derham decided to move the hospital to Singapore Island but would need time to organise a suitable site. In the interim, on 6 January 1942, 20 of the unit’s nurses were detached to the 2/4th CCS, while by the same date some 36 others and around 40 other staff had been detached to the 2/13th AGH at Tampoi, along with scores of patients.

The 2/10th AGH nurses, among them their matron, Dot Paschke, arrived at Mengkibol on 7 January – this time without “the usual collection of Chinese amahs and cooks,” which had “bolted into the blue,” and exchanged greetings with Elaine and the other 2/4th CCS nurses (Hamilton, p. 34). On 13 January, Matron Paschke left Mengkibol with the commanding officer of the 2/10th AGH, Colonel Edward Rowden White, to inspect the site chosen on Singapore Island for the unit’s occupation – Oldham Hall, a Methodist boarding school on Barker Road. In double time Matron Paschke and Colonel White converted the school into a clean and functional 200-bed hospital, and by 15 January the unit had completed its relocation, and the staff had begun to return from detachment.

The 2/4th CCS received its first Australian battle casualties on the night of 14 January. That day, shortly after 4.00 pm, B Company of the 2/30th Battalion ambushed Japanese troops at Gemencheh Bridge, located 50 kilometres to the west of Segamat. This was the first time that Australian troops had engaged Japanese soldiers, and it resulted in five Australian casualties.

The following day the main force of the 2/30th Battalion, together with elements of the 2/4th Anti-Tank Regiment, made further contact with Japanese forces outside Gemas in a battle that lasted two days. Although the Australians scored a tactical victory, they did little to slow the Japanese advance and sustained many casualties. At about 6.00 pm on 15 January a convoy arrived at the 2/4th CCS with 36 casualties, and from that time to 6.00 am the following morning, 165 cases were admitted to the unit and 35 operations carried out. From that time on, the casualties kept coming in.

BACK IN SINGAPORE

On 19 January, with no Commonwealth troops now remaining between the 2/4th CCS and Japanese positions, Lt. Colonel Hamilton was ordered to send the unit’s nurses to the 2/10th AGH on Singapore Island and to move the unit to its fallback position at Fraser Estate rubber plantation, near Kulai in southern Johor. Accordingly, that night, Elaine and her seven colleagues set out for Oldham Hall and arrived early the next day.

While the nurses were at Oldham Hall, the 2/4th CCS continued to retreat southwards. After four days at Fraser Estate, on 25 January the unit relocated to the old psychiatric hospital at Johor Bahru (not the site at Tampoi, but another hospital on the waterfront, across the strait from Singapore Island). On 28 January the unit moved again, this time to the Bukit Panjang English School on Singapore Island. Despite its frequent relocation, the unit had treated 1,600 battle casualties since 14 January. Meanwhile, on 25 January the 2/13th AGH had completed its own evacuation, returning to St. Patrick’s School.

Elaine and the other nurses rejoined the 2/4th CCS at Bukit Panjang on 30 January. Lt. Colonel Hamilton had driven over personally to Oldham Hall to tell them. They were thrilled at the idea of returning to their unit and hastily packed their belongings. When they arrived at Bukit Panjang the orderlies greeted them with cheers, and their presence had a marked effect on the morale of the patients and the other staff.

Early the next morning, after the last Commonwealth troops had crossed the Causeway from the peninsula to Singapore Island, British engineers set off two explosions on it to slow the Japanese advance onto the island. The first destroyed the lock’s lift-bridge, while the second caused a 21-metre gap in the structure. The breaches bought Commonwealth forces just eight days’ respite. Meanwhile, the whole of the Malay Peninsula was now in Japanese hands. It had taken just seven weeks for the Imperial Japanese Army to reach Johor Strait.

On that same day, 31 January, the nurses were separated again, and Elaine, Peggy, Kath and Bessie said goodbye to Millie, Shirley, Mavis and Mina, who had been detached to the 2/13th AGH at Katong at the request of Lt. Colonel J. G. (Glyn) White, second in command to Colonel Derham.

With the Japanese held temporarily at bay by the waters of the Johor Strait, military admissions to the 2/4th CCS, apart from bomb-blast casualties, were confined mainly to cases of exhaustion and sickness, Elaine and other staff experienced a period of relative quiet. There were, however, plenty of other concerns for the unit. The Bukit Panjang English School was located close to oil tanks and factories targeted by Japanese bombers, and some of the bombs fell close enough to the school to cause anxiety among the patients. In addition, flak from British ack-ack shells regularly fell on the school.

On 4 February a new and disturbing problem emerged for the 2/4th CCS. Japanese artillery had begun to range in on Australian artillery positions set close to the school, and stray shells caused a number of casualties. That afternoon Lt. Colonel Hamilton sent Bessie, Peggy, Kath and Elaine back to Oldham Hall, and two days later, on 6 February, the unit relocated once again, this time to the Swiss Rifle Club, around five kilometres southeast of the school. This time, the nurses did not return.

THE FINAL DAYS

On the night of 8 February Japanese troops began to cross Johor Strait. By the morning they had established a beachhead on the northwestern corner of Singapore island, despite strong opposition from Australian troops. Within a week, Singapore – the great fortress – would fall.

Meanwhile, at Oldham Hall, Elaine, Peggy, Kath and Bessie, together with their 2/10th AGH colleagues, worked under increasingly difficult conditions. There were continual air raids, and shells fell in and around the hospital area. After the Japanese landing, casualties poured in, operating theatres worked around the clock, and the wards became so overcrowded that men were lying on mattresses on the floor while others waited outside.

Reports of Japanese atrocities in Hong Kong and elsewhere had been circulating for some time, and already in January, Colonel Derham had asked Major General H. Gordon Bennett to evacuate the AANS nurses. Bennett had refused, citing the damaging effect on morale. Derham then instructed Lt. Colonel Glyn White to send as many nurses as he could with Australian casualties leaving Singapore.

Naturally the nurses did not want to leave their patients; it was a betrayal of their nursing ethos, and they protested strongly. Ultimately, they had no choice, and on 10 February six nurses drawn from the 2/10th AGH embarked with several hundred 2nd AIF casualties on the makeshift hospital ship Wusueh. The following day a further 60 AANS nurses, 30 from each of the AGHs, boarded the Empire Star with more than 2,000 evacuees, mainly British army and naval personnel, and set out for Batavia.

On 12 February 65 AANS nurses remained in Singapore, but they too had to go. Late in the afternoon, a convoy of ambulances arrived at Oldham Hall. Elaine reluctantly took leave of the wounded soldiers in her care and then climbed into the waiting ambulances with Peggy, Kath, Bessie and their 2/10th AGH colleagues. They were driven along side streets through Singapore city to St. Andrew’s Cathedral, where they waited to rendezvous with the remaining 2/4th CCS and 2/13th AGH nurses. Once assembled, the nurses continued through the ruined city to Keppel Harbour. When the ambulances could go no further, the nurses got out and walked the remaining few hundred metres. At the wharves there was chaos, as hundreds of people attempted to board any vessel that would take them.

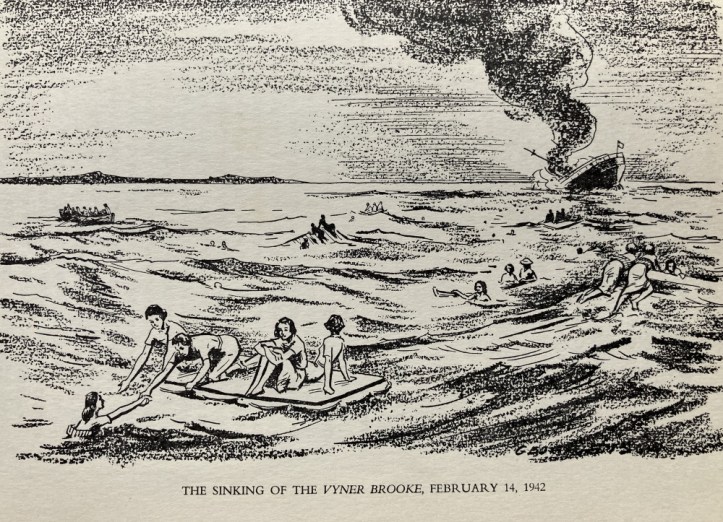

The VYNER BROOKE

Eventually a tug took Elaine and the others out to a small coastal steamer, the Vyner Brooke. It had once been used as a pleasure craft by Sir Charles Vyner Brooke, the colonial ruler of Sarawak on the island of Borneo. As darkness fell, the ship slid out of Keppel Harbour and after some delay began its journey south to Batavia. There were as many as 200 people aboard, mainly women and children, but also a number of men. Had they looked back at the receding city, they would have seen a waterfront entirely alight, and thick black smoke billowing high into the night sky.

During the night the Vyner Brooke’s captain, Richard Borton, slowly guided the vessel through the many islands that lined the passage between Singapore and Batavia. The next day was Friday 13 February. With the ship at anchor in the lee of an island – the better not to be spotted by Japanese planes – Matron Paschke, as the more senior of the two matrons, addressed her charges. She proposed a plan, according to which the nurses would be arranged into teams, each with an area of responsibility within the ship. The teams would maintain discipline and morale within their assigned area, would attend to wounded passengers should the ship come under attack and would evacuate the passengers, wounded or otherwise, before themselves. A group of nurses, including Elaine, Beth Cuthbertson of the 2/10th AGH, and Veronica Clancy of the 2/13th AGH, would stay aboard to check for stragglers before jumping over the side. The Vyner Brooke was equipped with six lifeboats, three on either side, as well as stacks of life rafts, so there was a good chance that every passenger would have something to hold onto. Moreover, they had been issued with lifebelts the previous evening, so at the very least would be able to float.

Saturday 14 February dawned bright and clear. After another night of slow progress through the islands, the Vyner Brooke lay hidden at anchor once again. The ship was now nearing the entrance to Bangka Strait, with Sumatra to the starboard side and Bangka Island to port. Suddenly, at around 2.00 pm, the Vyner Brooke’s spotter picked out a plane. It circled the ship and flew off again. Capt. Borton, guessing that bombers would soon arrive, sounded the ship’s siren. The nurses donned their lifebelts and tin helmets and took up positions lying on the ship’s deck. The captain then began to zig-zag through open water towards a large landmass on the horizon – Bangka Island. Sure enough, Japanese dive-bombers soon appeared, flying in formation and closing fast.

The planes grouped in two formations of three and flew towards the Vyner Brooke. As the ship zig-zagged, the bombs missed. The planes regrouped, flew in again, and scored three direct hits. The ship lifted and rocked with a vast roar when the first bomb exploded amidships. The next went down the funnel and exploded in the engine room. Then, as the passengers swarmed up to the open air, a third dealt the Vyner Brooke a last fatal blow. With a dreadful noise of smashing glass and timber, the ship shuddered and came to a standstill. It was lying 15 kilometres from Bangka Island.

The nurses carried out the plan agreed upon the previous day. They helped the women and children, the oldest people, the wounded, and their own injured colleagues into the three viable lifeboats, which were then lowered into the sea. One capsized upon entry into the water. Greatcoats and rugs were thrown down to the remaining two, which got away as the ship began to list alarmingly to starboard. After a final search of the ship it was the nurses’ turn to evacuate. They removed their shoes and their tin helmets and entered the water any way they could. Some jumped from the railing on the portside, others practically stepped into the water on the listing starboard side, others slid down ropes or climbed down ladders.

Elaine was a strong swimmer and managed to reach a rope trailing behind one of the lifeboats. As she was holding onto it, she beckoned to her 2/4th CCS colleague Mavis Hannah, who was clinging to an oar with Chris Oxley of the 2/10th AGH. However, Mavis could not swim and so was unable to join Elaine behind the lifeboat. Her inability to swim saved Mavis’s life.

BANGKA ISLAND

Elaine continued to cling to the rope and was eventually dragged in to shore. She joined a large group of nurses, civilians and crew around a bonfire on the beach. As Saturday night became Sunday more people joined, including British sailors and soldiers, many injured, whose ships had been sunk, like the Vyner Brooke, in Bangka Strait.

On Monday a decision was made to surrender en masse to Japanese authorities, and a deputation left for the nearest large town, Muntok, to negotiate this. A short while later all the civilian women and children of the group followed behind – save one, Mrs. Betteridge, a British woman whose husband lay among the injured on the beach.

Around mid-morning the deputation returned with a number of Japanese soldiers. The soldiers separated the survivors into three groups and proceeded to shoot or bayonet them in cold blood.

Elaine and 20 colleagues died on a lonely beach on Bangka Island on 16 February 1942. They were shot while standing in the sea. One colleague, Vivian Bullwinkel of the 2/13th AGH, miraculously survived.

Twelve of the 65 AANS nurses to leave Singapore that fateful day were lost at sea when the Vyner Brooke was sunk. Twenty-one died on Radji Beach. Thirty-two were made prisoners of war, eight of whom died. On 16 September 1945 the surviving 24 nurses were flown to Singapore and freedom, and in October they returned to Australia – ecstatic, but mourning those they had left behind.

In memory of Elaine.

SOURCES

- 2/30th Battalion A.I.F. Association, ‘2/30 Battalion First Anniversary – 22/11/1941 – Letter from NX29116 – Pte. Ray BROWN.’

- 2/30th Battalion A.I.F. Association, ‘War.’

- Ancestry.

- Arthurson, L., ‘The Story of the 13th Australian General Hospital, 8th Division AIF, Malaya,’ as reproduced by Peter Winstanley on the website Prisoners of War of the Japanese 1942–1945.

- Australian War Memorial, AWM52 11/6/6/4 – [Unit War Diaries, 1939-45 War] 2/4 Casualty Clearing Station Malaya, October 1941–February 1942.

- Gill, G. H. (1957) Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 2 – Navy, Vol. I – Royal Australian Navy, 1939–1942, Chap. 12 – Australia Station 1941 (pp. 410–463), Australian War Memorial.

- Hamilton, T. (1957), Soldier Surgeon in Malaya, Angus & Robertson.

- Hobbs, Maj. A. F., 2/4th CCS, Diary, presented in Lt. Colonel Peter Winstanley, ‘Prisoners of War of the Japanese 1942–1945.’

- Jeffrey, B. (1954), White Coolies, Angus & Robertson Publishers.

- Kirkland, I. (2012), Blanchie: Alstonville’s Inspirational World War II Nurse, Alstonville Plateau Historical Society Inc.

- National Archives of Australia.

- National Archives of Singapore, ‘The Causeway Centenary: The Causeway during the Battle for Singapore.’

- National Library of Australia, Oral History Program, ‘Mavis Hannah interviewed by Amy McGrath,’ interview conducted at Grove Hill House, Dedham, Colchester on 13 July 1981, transcript and audio.

- Shaw, I. W. (2010), On Radji Beach, Pan Macmillan Australia.

- Simons, J. E. (1956), While History Passed, William Heinemann Ltd.

- Walker, A. S. (1962), Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 5 – Medical, Vol. II – Middle East and Far East, Part II, Chap. 23 – Malayan Campaign (pp. 492–522), Australian War Memorial.

- Wigmore, L. G. (1957), Australia in the War of 1939–1945: Series 1 – Army, Vol. IV – The Japanese Thrust, Pt. I The Road to War, Ch. 4 – To Malaya (pp. 44–61), Australian War Memorial.

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS

- The Mail (Adelaide, 21 Dec 1935, p. 27), ‘Musical Notes.’

- Murray Pioneer and Australian River Record (Renmark, 1 Feb 1924, p. 23), ‘C. of E. Grammar School.’

- Murray Pioneer and Australian River Record (Renmark, 4 Apr 1924, p. 14), ‘Renmark Personals.’

- Murray Pioneer and Australian River Record (Renmark, 19 Dec 1924, p. 16), ‘Grammar School Concert.’

- Murray Pioneer and Australian River Record (Renmark, 13 Feb 1925, p. 4), ‘Renmark High School.’

- Murray Pioneer and Australian River Record (Renmark, 28 Aug 1925, p. 10), ‘From Our Letter Bag.’

- Murray Pioneer and Australian River Record (Renmark, 19 Nov 1926, p. 9), ‘Renmark High School Concert.’

- Murray Pioneer and Australian River Record (Renmark, 17 Dec 1926, p. 10), ‘High School Prizes.’

- Murray Pioneer and Australian River Record (Renmark, 16 Sep 1927, p. 6), ‘Renmark Scholarships Awarded.’

- Murray Pioneer and Australian River Record (Renmark, 30 Dec 1927, p. 6), ‘Renmark High School.’

- Murray Pioneer and Australian River Record (Renmark, 13 Jan 1928, p. 1), ‘Renmark High School Results.’

- Murray Pioneer and Australian River Record (Renmark, 21 Nov 1930, p. 10), ‘District Social and Personal Notes.’

- Murray Pioneer and Australian River Record (Renmark, 14 Jul 1938, p. 14), ‘Social Notes.’

- Murray Pioneer and Australian River Record (Renmark, 16 Jan 1941, p. 12), ‘Staff Nurse with A.I.F.’

- Murray Pioneer and Australian River Record (Renmark, 23 Jan 1941, p. 12), ‘Social Notes.’

- Murray Pioneer and Australian River Record (Renmark, 23 Jan 1941, p. 13), ‘Soldiers’ Social Functions.’

- Murray Pioneer and Australian River Record (Renmark, 13 Mar 1941, p. 12), ‘Nurse Balfour-Ogilvy “Somewhere in Malaya.”’

- Murray Pioneer and Australian River Record (Renmark, 16 Jul 1942, p. 6), ‘War Casualties.’

- Murray Pioneer (Renmark, 20 Sep 1945, p. 9), ‘Obituary.’

- News (Adelaide, 21 Dec 1932, p. 3), ‘Recess Time.’

- News (Adelaide, 13 Nov 1933, p. 5), ‘Nurses’ Exam Results.’

- The Register (Adelaide, 27 Jan 1927, p. 12), ‘The University of Adelaide.’

- The Register (Adelaide, Mar 1928, p. 9), ‘Piloted by Capt. H. C. Miller.’