AANS │ Matron │ Second World War │ Malaya │ 2/10th Australian General Hospital

Family Background

Olive Dorothy Paschke was born on 19 July 1905 in Dimboola, western Victoria. She was the middle daughter of five born to Ottilie Emma Kreig (1879–1970) and Heinrich Wilhelm Paschke (1867–1937).

Ottilie was born in Dimboola and grew up at ‘Pleasant View’, the family property just to the east of that town. Heinrich was born in Mount Gambier, South Australia, and moved to Victoria’s Wimmera District when he was seven years old.

Ottilie and Heinrich were married on 10 April 1901 at ‘Pleasant View’ and afterwards lived at Heinrich’s property at Wail, 10 kilometres southeast of Dimboola, where Heinrich was a farmer. In 1902 their first daughter, Ruth Evelyn Angela was born, followed in 1903 by Ada Louisa.

In 1904 Heinrich relinquished farming and took up commission agency work instead, and later sheep dealing. In 1905 Olive was born. Alice Edna followed in 1909, and finally in 1917 came Gwenyth.

Dot, as Olive was known from a young age, and her sisters went to Dimboola State School and later Dimboola High School. As she was growing up, Dot helped on her parents’ farm, attended church and excelled at tennis and golf.

Nursing and enlistment

When she finished school, Dot decided to become a nurse. She moved to Melbourne and began her training at the Queen Victoria and Allied Hospitals. After sitting her final Nurses’ Board examination in November 1933 and completing her training, she gained her registration in general nursing on 12 February 1934. She then undertook midwifery training at Queen Victoria and became registered on 14 February 1935.

Dot returned to Dimboola to take up an appointment as matron of Airlie Private Hospital. She stayed for four years, then returned to Melbourne to become assistant matron of the Jessie McPherson Hospital. Working under Dot at Jessie McPherson was a nurse by the name of Vivian Bullwinkel, who would serve with Dot in Malaya and eventually become the best-known nurse in Australia.

In 1940, following the German invasion of the Low Countries and France, Dot volunteered for service with the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS). She received her call up and enlisted on 11 January 1941 in the Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF). She was appointed matron of the 2/10th Australian General Hospital (AGH), a newly formed unit earmarked for service in Malaya. Fellow Victorians Caroline Ennis, Ruby Freeman, Nesta James and Rene Singleton were also attached to the 2/10th AGH that day and would serve under Dot.

The five Victorian recruits were each granted leave without pay until 23 January followed by pre-embarkation leave. On 2 February they boarded a train for Sydney and arrived the next day. They travelled to Darling Harbour and were taken by ferry to the Queen Mary, which was anchored off Bradley’s Point.

To malaya

The Queen Mary was due to carry approximately 5,750 troops of the 8th Division, 2nd AIF to Malaya following a British request for Australian reinforcements to join British and Indian troops in garrison duties. Accompanying the troops were the 2/10th AGH, the 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station (CCS) and several smaller medical units.

Once aboard, Dot and the other Victorians, together with their new Queensland and New South Wales counterparts, established an emergency hospital in the ship’s smoking room and on a lower deck.

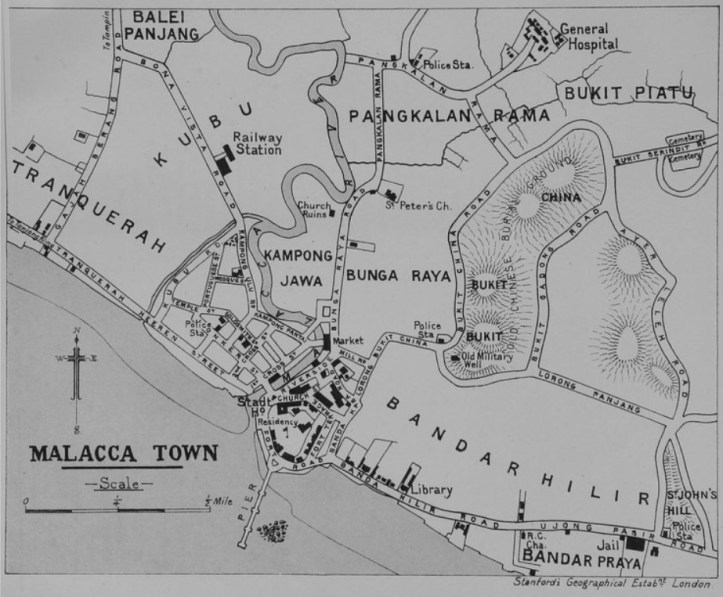

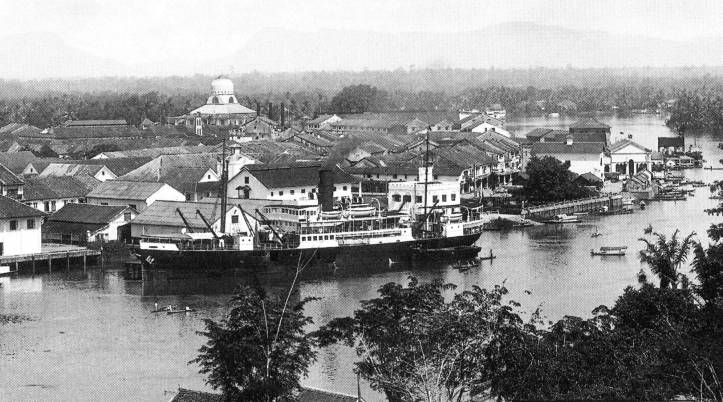

By 4 February the 8th Division troops had finished embarking, and, to the strains of ‘The Māori’s Farewell’, the Queen Mary weighed anchor and sailed away. Two weeks later, on 18 February, the ship arrived at Sembawang Naval Base on the north coast of Singapore Island. Dot and the nurses disembarked and were taken to adjacent railway sidings. They boarded an air-conditioned train that took them to the railhead town of Tampin. When they alighted early the next morning, they were taken by truck to Malacca.

Malacca was an old colonial town on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula, by all accounts very pleasant. The 2/10th AGH had been allocated several wings of the Colonial Service Hospital some little way out of town. The modern, five-storey building was set on a slight rise in spacious grounds bright with bougainvillea, frangipani and hibiscus.

Dot got to work straight away. There were immediately many cases of tropical illness among the troops to be handled and at the same time the hospital needed to be made shipshape. These tasks Dot handled with characteristic zeal and cheerfulness. Her long hours of duty were an inspiration to her nursing staff and were particularly valuable under the difficult conditions of the tropics.

The Australian Women’s Weekly visits Malaya

In April 1941 journalist Adele Shelton Smith of the Australian Women’s Weekly visited the 8th Division in Malaya with photographer Bill Brindle. On her final day she visited the 2/10th AGH in Malacca and spoke to Dot and some of her nurses. The resulting article, published on 3 May under the headline “‘They treat us like film stars’ says A.I.F. matron in Malaya,” aroused a good deal of feeling among some of the nurses, who thought it exaggerated their social lives. It makes for fascinating reading:

The people of Malaya cannot do enough for the Australian nurses. Off duty could be a whirl of gaiety were the girls not too interested in their work and in sightseeing. ‘Some days we feel like film stars,’ said Matron Paschke. ‘The local residents send us huge baskets of orchids, presents of fruit, and invitations to their homes or clubs.

I reserved the last day of my tour of the A.I.F. in Malaya for a visit to the Australian nurses. It was a splendid final flourish, as the matron, sisters, nurses and staff treated us royally. There were the same hospitality and eagerness to see someone from home which have been a feature of this tour. Matron Paschke and all the sisters and nurses who were not on duty or could be spared from the wards came into their attractive mess room for morning tea. They all looked extremely well and crisp in their grey cotton uniforms with red cotton capes. Like the men of the A.I.F. the nurses look wonderfully fit and have become used to the heat of the tropics. One sister said, ‘Nursing makes one a realist. I used to think the glamor of the tropics was a lot of “hooey,” but the colour of this country gets you. We are all so touched by the kindness of the people and the warm welcome they gave us. We have had quite a number of patients in the hospital but are not yet working at full pace, so we have been able to arrange generous time off. Some of us are playing golf, and whenever transport is available a party of us goes to the swimming club. Others play tennis. We are feeling very proud because an A.I.F. sister, partnered by one of our officers, won the club tennis tournament.’

One of the nurses told me of the journey to the hospital. ‘We left Singapore in the evening and were handed our first army ration – two doorstep sandwiches and an apple. We were glad to eat the doorsteps, though, before the night was very old,’ she said. ‘We arrived at the hospital very early in the morning while it was still dark. It all seemed so strange. Our amahs [housemaids] were all lined up to welcome us. They spoke no English and of course we couldn’t speak Malay. However, we all laughed and smiled a lot, and though we couldn’t understand a word of what they said we were all firm friends immediately. Our bedding was ready in our rooms, and we made up our beds and had a few hours’ sleep before exploring our new home.’

The nurses’ quarters are plain but comfortable. Some have rooms to themselves, others share in groups up to four. They are furnished with a metal bed, table, easy chair and small wardrobe. Some of the rooms look out through wide windows on marvellous views of deep green and blue hills. On every table there are framed family photographs and photographs of boyfriends. In each room the nurse’s battle dress – tin hat, respirator, and small knapsack – stands ready for any emergency.

The nursing staff had a week of intense A.R.P. and other war emergency training soon after they arrived in Malaya. The nurses’ mess is a lofty atap palm-thatched hut built in the shade of two wings of the hospital. Their dining-room is at one end and their recreation lounge at the other. ‘The Red Cross has been very good to us, both to the nurses and the patients,’ said Matron Paschke. ‘They supplied us with material for curtains and a sewing-machine, gramophone and records, and books. Local residents have entertained us most generously.’

I was the first Australian woman the nurses have seen here, so we had a fine old girls’ chat. They told me about their visits to rubber plantations, and where to shop for souvenirs, how to stop my make-up sliding off in the heat, and in exchange I told them all the gossip I could think of from home. We went on a tour of the wards and met the convalescent patients. The wards run the full length and breadth of the building. The outside walls are made entirely of glass and wood venetian shutters, allowing a maximum of ventilation.

The Red Cross has equipped a recreation centre in the convalescent ward, where the men can play various table games. The Red Cross Commissioner, Basil Burdett, showed us round his store, which is packed to the ceiling with packing-cases filled with luxury tinned foods, books, sports equipment, and medical supplies. ‘Many of the boys over here are putting on weight,’ a doctor told me. He said there was very little illness and not much work for the A.I.F. hospital. ‘We are watching them closely for any sign of fatigue or strain, and modifications would be made in their training if necessary. We have decided to keep the siesta period every day even if it is more of a fiesta for a lot of them at least they are relaxing. Our diet needs some adjustment here, but we are becoming accustomed to the different fruits and vegetables. In spite of the heat some of the boys still demand porridge for breakfast. The chief worry here is that illnesses last longer than they do at home. For instance, a common cold, which would clear up in a week or ten days at home, takes a month here. That is why we keep a close watch on the minor as well as major ailments.’

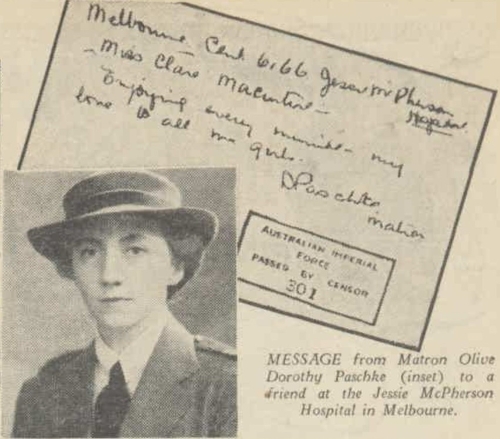

During the course of her tour, Shelton Smith collected hundreds of messages from 8th Division personnel in a red leather book addressed to friends and family in Australia – including one from Dot. It was addressed to Miss Clare Macintire of Jessie McPherson Hospital. “Enjoying every minute,” Dot wrote, “my love to all the girls. D. Paschke, matron.”

The Pacific War begins

The year passed peaceably by. Everything changed on 8 December, when Japan launched an invasion of Malaya. Amphibious troops landed at Kota Bharu in the north while Singapore was being bombed in the south. At the same time Pearl Harbour was being attacked and Hong Kong invaded. The Pacific War had begun.

Japanese infantry, backed by mechanized units and substantial sea and air power, surged down the Malay Peninsula and forced the severely outgunned Indian and British troops to retreat southwards.

Christmas approached. In a letter to her mother, who had moved to Stawell following Heinrich Paschke’s death in 1937, Dot told how the nurses and patients celebrated in traditional style. On Christmas Eve the nurses and orderlies decorated the hospital with trimmings supplied by the Red Cross. On Christmas Day the whole unit attended church parade at 6.00 am – an inspiring spectacle, wrote Dot, “one that I will never forget. After that, we, the nurses, medicos and orderlies, visited every ward and sang carols. While this was going on the air raid alarm went and we all donned our tin hats, put on our respirators at the alert, and went on singing.”

After the carol-singing, Dot and Mr. Basil Burdett, the Red Cross Commissioner in Malaya, presented a Red Cross Christmas parcel to everyone in the hospital. The Red Cross also provided the Christmas dinner, which consisted of turkey, plum pudding and all the odds and ends that go with the occasion, including caps and balloons. The day finished with a party given by the nurses for officers, orderlies and civilians. Mistletoe was arranged and the consequences caused much amusement.

On Boxing Day, the realities of war were brought a little closer by Japanese aircraft. Much bombing was done, but happily little damage. Air alarms occurred frequently, Dot told her mother, but there was never a sign of panic by anyone. In fact, there were many amusing situations occasioned by these alarms. Dot finished her letter by assuring her mother that all was well with the nurses in Malaya. And now that Christmas 1941 was gone, she hoped to celebrate the next one in Stawell.

All the while Japanese forces continued to push southwards, and by 29 December it had become clear that the 2/10th AGH would have to evacuate. Kuala Lumpur had been bombed, and Malacca was now in the direct path of the Japanese advance.

Evacuation to Singapore

Col. Alfred Derham, Commanding Officer of the Australian Army Medical Corps in Malaya, decided to move the hospital to Singapore Island but would need time to organise a suitable site. In the interim, 20 nurses were detached to the 2/13th AGH, which had arrived in Singapore on 15 September and was based in a psychiatric hospital in Tampoi in the southern Malay Peninsula. On 5 January 1942, 16 more nurses and around 40 other staff were detached to the 2/13th AGH. Scores of patients had also been moved south from Malacca to Tampoi. The following day, 6 January, 20 more 2/10th AGH nurses, including Dot, were detached to the 2/4th CCS, which had by now located to the Mengkibol Estate, a rubber plantation five kilometres to the west of Kluang.

On 13 January, Dot left Mengkibol with the CO of the 2/10th AGH, Col. Edward Rowden White, to inspect the site chosen on Singapore Island for the unit’s occupation – Oldham Hall, a Methodist boarding school on Barker Road. In double time Dot and Col. White converted the school into a clean and functional 200-bed hospital, and by 15 January the unit had completed its relocation, and most staff had returned from detachment.

In the meantime, on 14 January Australian 8th Division troops had entered combat for the first time in northern Johor. Although they scored a tactical victory against a Japanese force near the town of Gemas, the following days much bloodier battles fought, resulting in convoys of Australian casualties for the 2/4th CCS, the 2/13th AGH at Tampoi and the 2/10th AGH at Oldham Hall.

As more and more casualties arrived at Oldham Hall, other buildings were requisitioned for the hospital’s use, first Manor House, then nearby bungalows. By 31 January the 2/10th was caring for more than 600 patients. Throughout this time Dot’s spirit remained undaunted.

By the night of 25 January, the 2/13th AGH had followed the 2/10th AGH back to Singapore Island. It reoccupied St. Patrick’s School, where the unit was first based upon its arrival in September.

On 28 January, the 2/4th CCS followed the other two medical units to Singapore Island, relocating to Bukit Panjang English School. Then, on the night of 30 January, the final Commonwealth troops crossed the Causeway from the Malay Peninsula to Singapore Island. The next morning it was blown up. Soon after, the Imperial Japanese Army reached the northern shore of Johor Strait and on 2 February began a ferocious artillery bombardment of the island. The final battle was about to begin.

The Final Days of Singapore

On 4 February several shells fell a short distance from Oldham Hall. Three days later, three staff members were killed and several injured. To make matters worse, the large British guns to the south of the hospital were returning fire, so artillery was travelling over the hospital in both directions.

On the night of 8 February Japanese troops began to cross Johor Strait. By the morning, they had established a beachhead on the northwestern corner of Singapore island, despite strong opposition from Australian troops. The heavy fighting produced many casualties. At Oldham Hall, the wards became so overcrowded that men were lying on mattresses on the floor while others waited outside. Operating theatre staff worked around the clock, treating severe head, thoracic and abdominal injuries. There was little respite for staff when off duty either, as the constant pounding of bombs and shells meant that sleep was hard to come by.

With Singapore’s fate all but certain, a decision was made to evacuate the nurses. Already in January, following reports of Japanese atrocities in Hong Kong, Col. Derham had asked Maj. Gen. H. Gordon Bennett, commanding officer of the 8th Division in Malaya, to evacuate the AANS nurses. Bennett had refused, citing the damaging effect on morale. Col. Derham then instructed his deputy, Lt. Col. Glyn White, to send as many nurses as he could with Australian casualties leaving Singapore.

The nurses did not want to leave their patients. It was a betrayal of their nursing ethos and they protested strongly. Ultimately, of course, they had no choice, and on 10 February, six of Dot’s 2/10th AGH nurses embarked with 300 wounded on the makeshift hospital ship Wusueh. On 11 February a further 59 AANS nurses, drawn from both AGHs and chosen by Dot, boarded the Empire Star.

Now only 65 AANS nurses remained in Singapore. On 12 February Dot drove Winnie Davis, Jessie Blanch, Dot Freeman, Beth Cuthbertson, Clarice Halligan and Betty Jeffrey from Oldham Hall to Manor House, where, according to Betty Jeffrey in White Coolies, there were wounded men everywhere. They were “in beds, on stretchers on the floor, on verandas, in garages, tents, and dugouts.” Meanwhile, low-flying planes were machine-gunning all around them. At 1.45 pm a car arrived to collect the six to drive them back to Oldham Hall, from where they would be taken by ambulance to Keppel Harbour. They flatly refused to go; there was so much to be done. “Wounded were arriving constantly,” writes Betty Jeffrey, “no hospital ships were in Singapore to relieve the congestion. Our two-hundred-bed Manor House hospital…was rapidly approaching the one-thousand mark.” Dot ordered them to leave, and that was that. They felt dreadful leaving the wounded soldiers behind (Jeffrey, pp. 2–3).

Back at Oldham Hall, the nurses were picked up and joined a convoy of all remaining 2/10th AGH nurses, collected from the hospital’s various outbuildings. The ambulances drove along side streets through Singapore city to St. Andrew’s Cathedral, where they were joined by the remaining nurses of the 2/13th AGH and the 2/4th CCS.

When the siren sounded all clear, the 65 AANS nurses proceeded to Keppel Harbour until the ambulances could go no further, whereupon the nurses got out and walked. Betty Jeffrey describes an apocalyptic scene:

Singapore seemed to be ablaze. There were fires burning everywhere behind and around us and on the wharf hundreds of people trying to get away, long queues of civilian men and women…Masts of sunken ships were sticking up out of the water [and] and dozens of beautiful cars had been dumped (Jeffrey, p. 4).

Vyner Brooke

Dot and the others were ferried out to the small coastal steamer Vyner Brooke, lying at anchor in the harbour. On board were as many as 150 people – women, children, old and infirm men. As darkness fell, the ship slipped out of Keppel Harbour and, after straying into a minefield and spending time extricating itself, began its journey south. Behind the Vyner Brooke the night was red with the reflection of flame, and thick black smoke rose into the sky above the devastated city.

That night the Vyner Brooke made little progress. Friday was spent hiding among the hundreds of small islands that line the passage between Singapore and Batavia. Dot and Matron Irene Drummond of the 2/13th AGH used the time wisely. Anticipating a Japanese attack, they gave instruction in lifeboat drill, distributed life belts, and ordered the nurses to prepare dressings and bandages. They formulated a plan for their charges to execute when the time came.

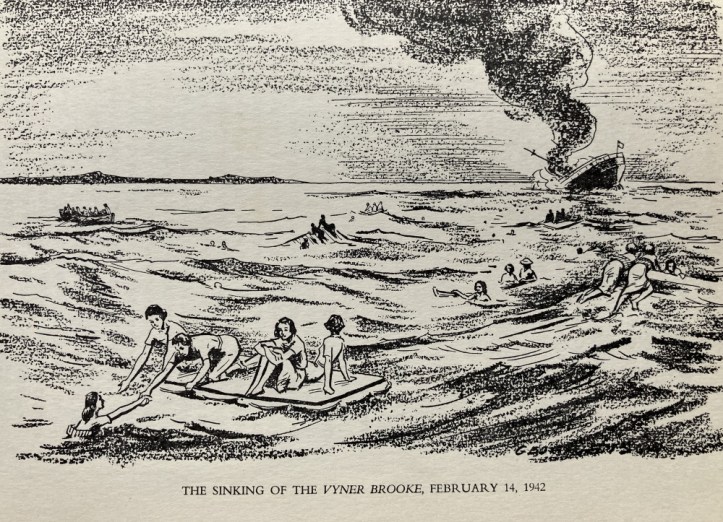

By the morning of Saturday 14 February, Captain Borton was approaching the entrance to Bangka Strait. To the right lay Sumatra; to the left, Bangka Island. Suddenly, at around 11.00 am, a Japanese plane swooped over, then flew off again. At around 2.00 pm another plane approached before flying off. The captain, anticipating the imminent arrival of Japanese dive-bombers, sounded the ship’s siren and began a run through open water. When a squadron of dive-bombers appeared on the horizon, Borton commenced evasive manoeuvres.

As the bombers approached, the Vyner Brooke zigzagged wildly at full speed. The first wave of bombs missed the ship. The planes banked, lined up again, and came in for a second run. This time a bomb struck the forward deck, killing a gun crew. Another entered the ship’s funnel and exploded in the engine room; the Vyner Brooke lifted and rocked with a vast roar. A third tore a hole in the side, and the Vyner Brooke began to list. It was doomed. To make matters worse worse, the aircraft had strafed the ship, knocking out the three portside lifeboats and badly damaging one of the three starboard lifeboats.

Dot’s organisation of those aboard the Vyner Brooke after the bombing was masterly. She oversaw the plan that she and Matron Drummond had devised the previous day, and only when she had seen all civilians placed in boats would she allow her nurses to leave. She could not swim, yet she gave the order to abandon the sinking ship as calmly as though it had been an everyday order.

Finally, Dot herself jumped overboard and managed to reach a life raft on which there were seven other nurses – Iole Harper, Myrtle McDonald and Merle Trenerry of the 2/13th AGH, Mary Clarke, Caroline Ennis and Betty Jeffrey of the 2/10th AGH, and Millie Dorsch of the 2/4th CCS. Caroline Ennis had taken charge of two small children, one of whom Betty Jeffrey had plucked from the sea, and there were several crew members as well. As a non-swimmer, Dot was exceedingly proud of herself.

The current pulled them away from the sinking ship and into Bangka Strait. They drifted all night long, roughly parallel to the Bangka Island coastline. At one point they came close to shore near a lighthouse, before being pulled back out to sea by the current. The occupants alternated between sitting on the raft and drifting beside it in the water, hanging onto its grabrope.

When daylight came, Betty Jeffrey, Iole Harper and two Malay crew members entered the water to swim beside the raft, to lighten the load. Suddenly the raft was caught in a current and carried swiftly out to sea. Dot, Myrtle, Merle, Mary, Caroline and Millie were never seen again.

Six other AANS nurses were lost at sea that day. Mona Wilton of the 2/13th AGH was struck on the head by a falling raft and drowned as the Vyner Brooke was sinking. Vima Bates of the 2/13th AGH was seen in the water and then never seen again. Nell Calnan, Jean Russell and Marjorie Schuman of the 2/10th AGH, and Kath Kinsella of the 2/4th CCS, disappeared without a trace.

Fifty-three nurses washed ashore on Bangka Island – in lifeboats, rafts, clinging to wreckage or simply drifting in their lifebelts. Twenty-one were killed in a horrific massacre on a beach near the town of Muntok, which only Vivian Bullwinkel of the 2/13th AGH survived. Vivian joined the remaining 31 in Japanese internment camps for the next three-and-a-half years. Only 24 came home.

In memory of Dot.

Sources

- Jeffrey, B. (1954), White Coolies, Angus & Robertson Publishers.

- McCarthy, J. (2000), ‘Paschke, Olive Dorothy (1905–1942)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- National Archives of Australia.

- Shaw, I. W. (2010), On Radji Beach, Pan Macmillan Australia.

- Simons, J. E. (1956), While History Passed, William Heinemann Ltd.

Sources: Newspapers

- The Argus (Melbourne, 24 Jun 1944, p. 16), ‘Family Notices.’

- The Australian Women’s Weekly (3 May 1941, p. 7), ‘“They treat us like film stars” says A.I.F. matron in Malaya.’

- The Australian Women’s Weekly (24 May 1941, p. 9), ‘A.I.F. in Malaya sent these messages home.’

- The Australian Women’s Weekly (28 Mar 1942, p. 7), ‘Home Again – A.I.F. Nurses from Malaya.’

- The Horsham Times (7 May 1901, p. 1), ‘Social.’

- The Horsham Times (26 Mar 1937, p. 5), ‘Obituary.’

- Weekly Times (Melbourne, 28 January 1942, p. 26), ‘Christmas Dinner Under Fire.’