AANS │ Lieutenant │ Second World War │ Malaya

FAMILY BACKGROUND

Rubina Dorothy Freeman, known as Ruby when she was younger and Dot when she was older, was born on 17 June 1910 in Randwick, Sydney. She was the daughter of Ada Beatrice Little (1879–1913) and Albert Edward Freeman (1878–1947).

Ada was born in Seymour, Victoria and worked for a time as a shop assistant. Albert was born in Redesdale, Victoria and worked as a commercial traveller. They were married in 1906, and a year later their first child, Melva Victoria Freeman, was born in Shepparton in Victoria’s Goulburn Valley.

The family moved to Melbourne and in 1909 were living at 45 Weigall Street in Prahran. Soon after they moved to Sydney, where Ruby was born in 1910. By 1913 they had returned to Melbourne. In April that year, when Ruby was only two years old, Ada Freeman died of pleurisy. She had only just given birth to Keith Albert Harris Freeman (1913–1978).

In 1914 Albert married Maude Marie Schweicker. They had three children, all of whom died very young. Tragically, Maude herself died in 1923 at the age of 37 after suffering peritonitis leading to toxaemia. Later that year Albert was married for a third time, to Emily Susannah Bindle. Emily and Albert had a daughter, Constance.

NURSING

After completing her schooling, Ruby decided to become a nurse and in the early 1930s began her training at the Alfred Hospital in Melbourne. In March 1935 she passed her final examination and gained her certificate in general nursing. Two years later she trained in midwifery at the Women’s Hospital in Melbourne and became registered on 6 April 1938. In the late 1930s Ruby became a Melbourne District Nursing Society (MDNS) nurse.

Melva Freeman also became a nurse. She trained at Mooroopna Hospital, near Shepparton, and attained her certificate in general nursing at the same time as Ruby did. She then trained in midwifery at Crown Street Women’s Hospital in Sydney.

ENLISTMENT

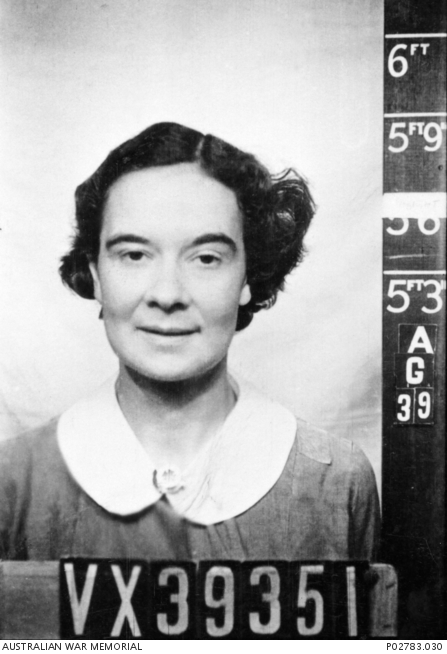

When war broke out in Europe in 1939 many Australians enlisted for service, particularly after May 1940, when Germany invaded France and the Low Countries. Ruby was one of them. In 1940, while still working as a district nurse, she volunteered to serve in the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS). She eventually received her call up and on 11 January 1941 was appointed to the Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF) and attached to the 2/10th Australian General Hospital (AGH). Although she did not yet know it, she was set for service in Malaya.

Other Victorian nurses attached to the 2/10th AGH that day were Nesta James, Caroline Ennis, Dot Paschke, and Rene Singleton from Maffra, in far eastern Victoria, with whom Ruby would become great friends – and whose tragic fate Ruby would share.

The five Victorian recruits were granted leave without pay until 23 January and then pre-embarkation leave. On 2 February Ruby – or Dot, as her new colleagues called her – Rene, Nesta, Caroline and Dot Paschke, who was to be the unit’s matron, boarded a train in Melbourne and arrived in Sydney the following day. They proceeded to Darling Harbour and were taken by ferry to the mighty liner Queen Mary, which was lying at anchor at Bradley’s Point and doing duty as a troopship.

The QUEEN MARY

The Queen Mary was due to carry more than 5,500 troops of the 22nd Brigade, 8th Division to Malaya following a British request for Australian reinforcements to join British and Indian troops in garrison duties. Accompanying the troops were the 2/10th AGH, the 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station (CCS), with eight AANS nurses attached, and several smaller medical units.

On 4 February the Queen Mary weighed anchor and sailed away. Outside the Heads the ship joined the Aquitania and the Nieuw Amsterdam, which together were carrying thousands of Australian and New Zealand troops to Bombay, from where they would transship for the Middle East. After a few days the Mauretania joined the convoy.

Just south of Sunda Strait the Queen Mary circled the other ships and steamed off towards Malaya, and on the morning of 18 February arrived at Sembawang Naval Base on the north coast of Singapore Island. Sitting at breakfast as the ship was pulling in, Dot and the others could see attractive white bungalows set against the vivid greens of the foliage on the hillsides.

MALACCA

The nurses disembarked and boarded a train for Malacca, on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula. Early the next morning they arrived at the Colonial Service Hospital, where their hospital was being established.

Initially the heat was enervating, but Dot and her colleagues soon grew accustomed to it and began to feel at home. They were kept busy looking after the troops of the 22nd Brigade but still had plenty of time for such activities as shopping excursions, golf, tennis and swimming, dancing, Sampan picnics, and chicken-suppers on the beach. They were made honorary members of European-only clubs. They were treated by well-to-do residents to curry tiffin, birds’ nest soup, fried rice and mushrooms, and other exotic dishes. They visited tin and gold mines and rubber estates and were taken on long drives through the delightfully verdant countryside.

Dot was granted leave from 23 to 25 May and took it with Rene Singleton and one or two others. They quite possibly travelled to Singapore, a popular destination with all the nurses. She was granted more leave from 3 to 7 August, this time without Rene, and from 1 to 8 October and 15 to 19 November, again with Rene.

WAR

For 10 peaceful months Dot had carried out her work and enjoyed her time off. All that changed on 8 December, when soon after midnight a force of some 5,000 troops of the Imperial Japanese Army launched an amphibious assault at Kota Bharu on the Malay Peninsula’s northern coast. Four hours later, as many as 17 Japanese bombers attacked Singapore Island.

Over the next nine weeks, Japanese infantry, backed by mechanized units and substantial sea and air power, surged down the Malay Peninsula in three lines of attack at a steady pace of 15 kilometres a day, forcing severely outgunned British and Indian troops to retreat southwards. The illusion that had held for so long – that Malaya was well defended – was shattered.

In late December, Col. Alfred Derham, officer in charge of the 8th Division’s medical units in Malaya, decided that the 2/10th AGH, lying in the direct path of the coastal prong of the Japanese advance, should be relocated to Singapore Island. On 6 January 1942, as part of the relocation plan, Dot, Rene and 18 other 2/10th AGH nurses were detached to the 2/4th CCS, based at Mengkibol Estate, a rubber plantation five kilometres to the west of Kluang. They arrived the following day.

Dot and Rene returned to the 2/10th AGH on 17 January, each having been promoted to the rank of sister. The unit had completed its relocation to Singapore and was based at Oldham Hall, an Anglo-Chinese boarding school, and nearby Manor House. Other buildings in the vicinity were progressively taken over as the front crept ever closer.

By now Australian troops had engaged in combat for the first time, ambushing bicycle-mounted Japanese infantry near Gemas on 14 January, followed by further actions over the next two days. The tactical victories did little to stop the Japanese advance and sent scores of Australian casualties to the 2/4th CCS at Mengkibol, to the 2/10th AGH at Oldham Hall, and to the 2/13th AGH, which had arrived in Singapore in September and was based at a psychiatric hospital in Tampoi, in the far south of the Malay Peninsula.

Japanese momentum continued unabated until, by the end of January 1942, all British, Indian and Australian troops and medical units had crossed to Singapore Island and the causeway linking the island and the peninsula had been blown in two places.

ESCAPE FROM SINGAPORE

When Japanese forces reached Johor Strait, they launched a furious artillery assault on the island. On the night of 8 February, they crossed the strait. Pressure mounted on 8th Division headquarters to evacuate the Australian nurses, and on 10 February six of Dot’s 2/10th AGH colleagues embarked for Batavia with several hundred 8th Division casualties on a makeshift hospital ship, the Wusueh. The following day a further 60 AANS nurses, 30 from each of the AGHs, boarded the Empire Star with more than 2,000 evacuees, mainly British army and naval personnel, and set out for Batavia. Both ships reached the capital of the Netherlands East Indies, not without trouble, and the 66 evacuated nurses eventually made it home to Australia. Now only 65 AANS nurses remained in Malaya.

Later that day Matron Paschke drove Dot and her 2/10th AGH colleagues Jessie Blanch, Winnie May Davis, Beth Cuthbertson, Clarice Halligan and Betty Jeffrey from Oldham Hall to Manor House, where, according to Betty Jeffrey, in her book White Coolies, there were wounded men everywhere. They were “in beds, on stretchers on the floor, on verandas, in garages, tents, and dug-outs” (Jeffrey, p. 2). Meanwhile, low-flying planes were machine-gunning all around them. At 1.45 pm a car arrived to collect the six to drive them back to Oldham Hall, from where they would be taken by ambulance to Keppel Harbour. They flatly refused to go; there was so much to be done. “Wounded were arriving constantly,” writes Betty Jeffrey, “no hospital ships were in Singapore to relieve the congestion. Our two-hundred-bed Manor House hospital … was rapidly approaching the one thousand mark” (Jeffrey, p. 3). Nevertheless, Matron Paschke ordered them to leave, and that was that. They felt dreadful leaving the wounded soldiers – those “superb fellows” – behind.

Once back at Oldham Hall, Dot, Jessie, Winnie, Beth, Clarice and Betty were picked up and joined a convoy of all remaining 2/10th AGH nurses, collected from the hospital’s various outbuildings. The ambulances drove along side streets through Singapore city to St. Andrew’s Cathedral, where, during one of the heaviest bombing raids Singapore had yet experience, the nurses had their names and numbers recorded. In time they were joined by the remaining nurses of the 2/13th AGH and the 2/4th CCS, whose names were added to the list.

When the siren sounded all clear, the 65 AANS nurses proceeded to Keppel Harbour until the ambulances could go no further, whereupon the nurses got out and walked. Betty Jeffrey describes an apocalyptic scene:

Singapore seemed to be ablaze. There were fires burning everywhere behind and around us and on the wharf hundreds of people trying to get away, long queues of civilian men and women … Masts of sunken ships were sticking up out of the water [and] and dozens of beautiful cars had been dumped (Jeffrey, p. 4).

The nurses were taken out by tug to a small coastal steamer, the Vyner Brooke, and with as many as 150 others slipped away as evening fell. That night the Vyner Brooke made little progress and spent much of Friday hiding among small islands. By the morning of Saturday 14 February, Capt. Borton was approaching the entrance to Bangka Strait. At about 2.00 pm, six Japanese bombers were seen approaching. Borton began evasive manoeuvres but ultimately to no avail: after three direct strikes, the Vyner Brooke shuddered, came to a standstill and began to list. It was lying 15 kilometres from Bangka Island.

After helping passengers to evacuate into the three viable lifeboats, Dot and the other nurses abandoned ship. Dot managed to reach shore, perhaps on a raft or on a piece of wreckage, but twelve of her colleagues did not.

PRISONERS OF JAPAN

Once ashore Dot was taken by Japanese soldiers – who had overrun the island during the night – to a place of internment in the nearby town of Muntok. There she was reunited with other surviving passengers of the Vyner Brooke, including many of her own nursing colleagues. Interned also were hundreds of survivors of other ships sunk by the Japanese navy and air force in Bangka Strait.

In a day or two the nurses, who now numbered 31, were taken with the other internees to a site on the edge of town, and here Vivian Bullwinkel of the 2/13th AGH joined them. She had survived an atrocious massacre of scores of service personnel, merchant sailors, civilians – and 21 of the nurses’ own colleagues. Of the 65 who had set out from Singapore on that fateful day, only 32 now survived.

So began a long period of captivity for Dot, the other surviving nurses, and the hundreds of other women, children and men. They were held in six camps on Bangka Island and in southern Sumatra. They were subjected to systematic abuse and random acts of violence. They were slapped, yelled at, made to stand in the sun and threatened with starvation. They were subjected to psychological torture.

It was in the final two camps, Muntok on Bangka Island and Belalau on Sumatra, that the nurses and other internees fared worst. They suffered debilitating diseases – beriberi, malaria, dysentery and ‘Bangka fever’ – and had life-saving medicines withheld. Along with many other internees, they began to die.

THE FINAL YEAR

On 8 February 1945, at Muntok camp, Dot and the others lost their first comrade, when Mina Raymont of the 2/4th CCS died of malaria. Then on 20 February, Dot’s great friend Rene Singleton died of beriberi. On 19 March Blanche Hempsted of the 2/13th AGH died too. Shirley Gardam of the 2/4th CCS followed on 4 April.

In April, the internees were transported to what would be their final camp, Belalau rubber plantation, near Lubuklinggau, on Sumatra. It lay deep in the jungle some 250 kilometres west of Palembang.

The three-day journey claimed many lives, and when they finally arrived at Belalau, Dot’s comrades continued to die. Gladys Hughes of the 2/13th AGH died on 31 May, followed by Winnie May Davis of the 2/10th AGH on 19 July.

Dot succumbed on 8 August. She had been ill for some time, as Betty Jeffrey tells us, “[with] malaria, dysentery, and beriberi, which would not let up. She was in hospital and died quite suddenly one night just after she and Flo Trotter had had a cup of tea and a chat. Flo was on night duty and was terribly shaken, as we all were” (Jeffrey, p. 178).

Elizabeth Simons of the 2/13th AGH writes in While History Passed how touched she had been by a little birthday present from Dot Freeman and Rene Singleton. “Little presents we would have scorned to give in other days were very precious. [A] small camp-made powder puff came my way in 1942 from Dorothy Freeman and Rene Singleton. Right then I had no powder to use it with, but I will always treasure that little thing, embroidered with a spray of blue flowers and my initial, in memory of two girls we buried in Sumatra” (Simons, p. 70). Later she wrote of Dot’s tragic death. “‘Dot’ Freeman, 2/10th A.G.H., another Victorian, was a sweet girl, with whom internment went very hard. She slipped out quietly one night early in August” (Simons, pp. 89–91).

Dot’s 2/10th AGH colleague Pat Gunther, in Portrait of a Nurse, also writes poignantly of Dot’s passing:

I had a message one day that Dot Freeman wanted to see me. I walked up to her hut to find her lying curled up in the foetal position. She told me she couldn’t straighten her legs. She couldn’t remember how long she had been like that, so I assumed she must have been sleeping. I told her not to worry, as I would arrange a hospital admission for her right away, and once there, she’d be alright. When thanking me, she said, “I’ll save a place for you.” We both knew she was dying.

In the late afternoons when I wasn’t having a rigor, I usually helped out with the coffin carrying, and collected wood on the way back. One day I said I couldn’t be carrier, but would lead out. Holding my head up to carefully keep to the track, the first cross I saw was Dot’s. It was like a slap in the face (Gunther, p. 85).

On 18 August, three days after Emperor Hirohito had announced Japan’s surrender, Pearl Mittelheuser of the 2/10th AGH died. Hers was the final and possibly most tragic death of all.

On 16 September the surviving 24 nurses were flown to Singapore and in October returned to Australia. They left behind 41 comrades, including Dot.

IN MEMORIAM

On 14 February 1953, the 11th anniversary of the sinking of the Vyner Brooke, a short dedication service was held to mark the opening of memorial gates at the entrance to the Alfred Hospital Nurses’ Home on Punt Road. The gates were erected by the Alfred Hospital Nurses’ League, whose members had been working to raise funds for the memorial since the end of the war, and honoured the memory of four Alfred trainees who had lost their lives during the war – Dot, Matron Gwladys Thomas (who was killed in a car crash in Egypt), Sister Eileen Rutherford (who lost her life on the Centaur) and Sister Frances Stevenson (who died of illness in Australia). Former matron-in-chief of the AANS Grace Wilson ceremonially unlocked the gates with the following words: “The nurses to whom these gates are dedicated gave their all. They should be a constant reminder to all of us to give nothing but the best that is in us.”

In memory of Dot.

SOURCES

- The Age (Melbourne, 16 Feb 1953, p. 5), ‘To Honor Nurses.’

- Ancestry.

- Anonymous, ‘Malaya,’ in Wellesley-Smith, A. and Shaw, E. L., eds. (1944), ‘Lest We Forget,’ Australian Army Nursing Service.

- Darling (née Gunther), P. (2001), Portrait of a Nurse, published by Don Wall.

- Jeffrey, B. (1954), White Coolies, Angus and Robertson.

- National Archives of Australia.

- Shaw, I. W. (2011), On Radji Beach, Pan Australia.

- Simons, J. E. (1954), While History Passed, William Heinemann Ltd.