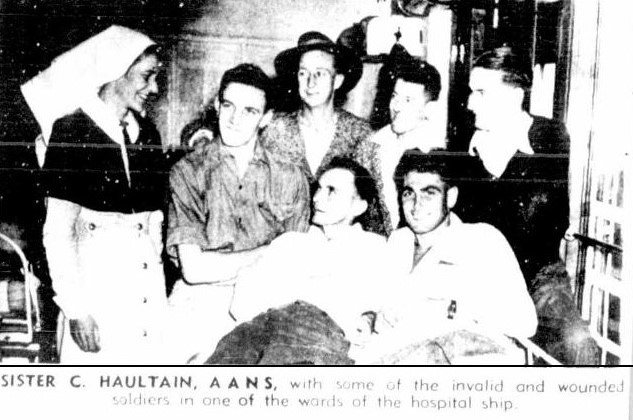

AANS │ Lieutenant │ Second World War │ 1st Netherlands Military Hospital Ship Oranje & 2/3rd Australian Hospital Ship Centaur

FAMILY BACKGROUND

Helen Frances Jane Cynthia Haultain, known as Cynthia, was born on 13 October 1904 in Calcutta, India. Her mother was Helen Caroline Hill and her father Henry Graham Haultain. Helen and Henry married in 1894 in Calcutta, where Henry was in the service of the Calcutta Police Force.

Cynthia had an older brother, Charles Theodore Graham (b. 1896), and a younger sister, Sybil Agatha (b. 1905).

In 1920 Mrs. Haultain and the children relocated from Calcutta to Sydney. They arrived on 14 June, but Cynthia’s father stayed in India, where he died in 1937. In Sydney, the girls attended Parramatta High School, and Cynthia gained her Intermediate Certificate in 1922.

NURSING

After finishing school, Cynthia decided to become a nurse. She undertook her training at the Coast Hospital (renamed Prince Henry Hospital in 1934), Little Bay, while living in Maroubra. She passed her Nurses’ Registration Board examination in May 1929 and gained her registration in November.

Meanwhile, Cynthia’s mother and sister were living at ‘Oranmore’ in Ingleburn, a town 40 kilometres southwest of Sydney. In 1926, Cynthia’s brother, Charles, who was a ship’s officer and later a commander, married Ruby Cust in Vancouver, Canada.

By 1930 Cynthia was nursing at Wentworth Falls in the Blue Mountains. In December of that year her engagement to Mr. Leslie Palmer was announced, but marriage did not eventuate. By 1933 she had moved to Newington State Hospital in western Sydney and was living in Auburn. At Newington she gained experience in respiratory nursing and operating theatre techniques, particularly for tuberculosis.

CAMP HOSPITALS AT HAY AND INGLEBURN

When war broke out, Cynthia, like so many of her peers, volunteered to serve with the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS). She was called up and on 15 May 1941 enlisted in the Australian Military Forces (AMF) at the rank of staff nurse. The following day she was detached to the camp hospital at Hay Internment Camp (later known as the 14th Australian Camp Hospital and also 205 Camp Hospital).

Cynthia made many friends in Hay. She was always ready to assist the local branch of the Red Cross, which had provided the hospital staff with many amenities. Even after her service at Hay had concluded, she stayed in contact with the friends she had made and maintained her interest in the work of the Red Cross. On 14 October Cynthia was promoted to the rank of temporary sister.

On 17 November Cynthia’s appointment to the AMF was terminated and the following day she enlisted in the Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF) at the rank of staff nurse. She had been selected for service on a hospital ship but for the time being remained detached to the camp hospital in Hay. On 10 December Cynthia went on pre-embarkation leave and upon her return to duty on 16 December was attached to the 102nd Australian Casualty Clearing Station (ACCS), based at the camp hospital in Ingleburn, southwestern Sydney.

Cynthia remained at the 102nd ACCS in Ingleburn until 21 January 1942. She then spent five days preparing for embarkation and on 26 January reported to Eastern Command in Sydney (possibly at Victoria Barracks). Here she met two other AANS nurses, Staff Nurse Eva King and Matron Anne Jewel, who were due to be appointed to the same hospital ship as Cynthia – the Oranje.

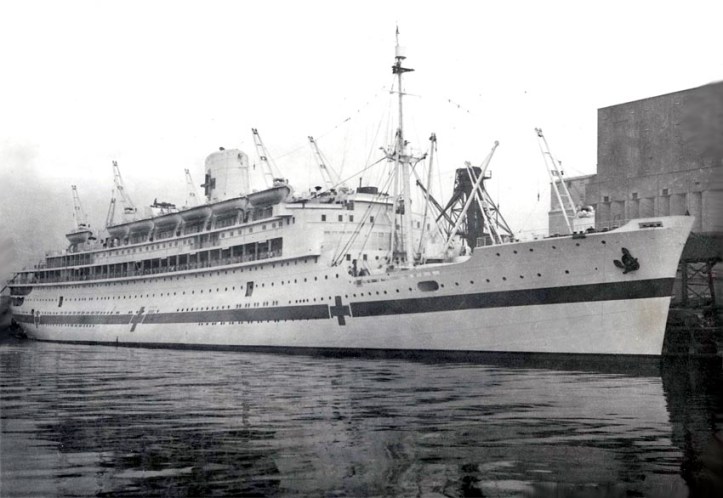

THE ORANJE

The Oranje was a Dutch passenger liner, the flagship of the Royal Netherlands Mail Line. Following the outbreak of war in Europe, it had become stranded in the Netherlands East Indies (NEI) and in February 1941 the NEI government offered the vessel to the Australian and New Zealand governments for the repatriation of sick and wounded Anzacs. On 1 April the Oranje arrived in Sydney from Surabaya and was moored at Cockatoo Island dockyard for conversion.

By the end of June, the Oranje had been recommissioned as the 1st Netherlands Military Hospital Ship Oranje. It was resplendent in white with a green band and red crosses and was ready for its maiden voyage. It would sail under Australian command but fly the Dutch flag. The bulk of its personnel, which included doctors, 30 nurses and 30 Voluntary Aid Detachments (VADs), were Dutch, although a small number of Australian and New Zealand medical personnel were on board to liaise between the casualties and the Dutch staff. Among the liaison officers was AANS nurse Sister Mary McFarlane from South Australia.

The Oranje departed Sydney on 3 July and travelled to Aden via Batavia and Singapore, then sailed up the Red Sea to Port Tewfik, Suez, where more than 600 Australian and New Zealand casualties were embarked over a number of days. On the return journey the ship sailed directly from Suez to Fremantle, crossing the Indian Ocean in record time, thence to Adelaide, Melbourne, Sydney, Wellington, and back to Sydney, arriving on 4 September.

On 24 October the Oranje set out on its second voyage to Suez. Following a similar route, the ship embarked nearly 550 patients quickly and efficiently and arrived back in Sydney on 11 December. By then Japan had invaded Malaya, the Philippines, Guam and Hong Kong, and bombed Singapore Island and Pearl Harbour, and the Pacific War had begun.

Following the Netherlands’ declaration of war against Japan, many of the Oranje’s Dutch medical personnel were ordered to return to the NEI, and Australians and New Zealanders were recruited to take their places – among them Cynthia, Eva and Anne.

On 27 January 1942 the three nurses boarded the Oranje and were formally attached to its staff. Once on board, they met Mary McFarlane, their South Australian colleague, and acquainted themselves with the layout of the ship. Later that day the Oranje steamed out of Sydney Harbour and set off on its third voyage.

The following morning the Oranje arrived at Port Melbourne, and three more AANS nurses boarded, Staff Nurse Margaret Adams, Sister Eileen Rutherford, and Staff Nurse Jenny Walker.

The ship left Melbourne and after stopping in Fremantle sailed directly to Aden. Due to the Japanese invasion of Southeast Asia and the southwest Pacific, the Oranje had avoided the usual route, which generally included stops at Colombo and/or Bombay. From Aden the Oranje continued as usual to Port Tewfik, the port of Suez, Egypt, where more than 600 Australian and New Zealand patients were embarked.

CYNTHIA’S FIRST LETTER

After the Oranje returned to Sydney on 9 March 1942, Cynthia wrote to friends in Hay providing an interesting account of her experiences. Her letter was published on 7 April in The Riverine Grazier. “I suppose you heard that I had been appointed to a hospital ship,” she wrote. “I suppose too, that you have heard all about her. Most of the nursing staff and doctors are Australians and New Zealanders.

The people are simply marvellous and our boys get absolutely everything they can possibly want. The ship is beautifully equipped, has a first rate theatre and X-ray plant, plaster rooms, and massage rooms, and even a corridor, which we call Macquarie Street, with specialists for ear, eye, nose and throat and skin, and dental treatment, to say nothing of a special sound-proof room for examining chests. The supply of linen is more than adequate; in fact all bed patients have their sheets and pyjamas changed twice a day – a thing that is rare even in a private hospital. The food is excellent and there is a good variety – plenty of fruit, milk, and vegetables.

Our trip was uneventful and a real rest. At one port [Aden] we were given a marvellous day. There are very few women there, in fact only 60, and over 6,000 men, so you can imagine how we were rushed! We spent all day sight-seeing and spending far more than we could afford in the bazaars, and went to a ball at the R.A.F. station at night. There were airmen from all over the world – English, Australian, New Zealand, South African, Canadian and American and one Indian, all such nice lads, very young and very keen to get to holts with Jerry. So far their only opponent has been the Italian Air Force which hasn’t been seen or heard of since the end of the Abyssinian campaign.

We arrived at our destination [Port Tewfik] early one morning and got down to real work when we embarked 600 patients. I wish you could have seen the organising of that embarkation! The boys were brought out in lighters and some stewards went round in a speed boat to give them hot drinks while they were waiting to come on board. As soon as they arrived they were drafted to their wards – it didn’t take longer than five minutes after they got up the gangway – where they were given a piping hot meal, and then a bath and bed. Some of them were utterly worn out, but they soon recovered. The stretcher cases were hoisted on to the sports deck by crane, and sent down to their respective wards in a cot lift, and it was no time before we had a ship full. I believe the most dangerous time of the whole trip is during the embarkation, as the hospital ship and lighters would make a ‘sitting’ shot for any enemy ’plane. That’s why things must be done quickly. We had three practices before we arrived, so learned to do things quickly and without confusion.

The boys were a delight to nurse – no trouble at all and most grateful for what was done for them. The Red Cross provided all sorts of handicrafts for them, and they took a great interest in weaving, embroidery, tapestry and leather work. Luckily I knew how to do all but the leather plaiting, and was able to teach them. The weaving – they made scarves – was particularly popular. The poor kids or rather 200 of them, had had all their kit burnt on the hospital train, when the luggage van caught fire. What worried them most was that all the gifts they had collected to take home, and all their snaps, had been destroyed; they worked feverishly at handicrafts so that they wouldn’t go home empty handed.

I thought the Hay Red Cross might like to know how the tussore [coarse silk] undershirts they sent had been appreciated. Perhaps you would let them know for me. It was frightfully hot in one spot, and the bed cases found the pyjama coats most uncomfortable, as when they got wet with perspiration, they seemed to tighten up under the arms. I asked Mr. Clarke, the Red Cross man, if he had anything light the boys could wear, and he came down with an armful of these tussore shirts – all marked as gifts of the Hay branch. The patients found them such a boon – light and beautifully roomy – that I have kept them for the next trip, as they were the last on board. The Red Cross provides such a lot of extras – underclothes, razors and blades (very popular), cigarettes, tobacco, sweets, cakes, slippers, canvas deck hats, glare glasses and a host of other things.

We had quite a lot of New Zealand boys on board. It was funny to hear them boosting their dearest little spot in earth, in opposition to the Aussies’ ‘God’s own country.’

FURTHER VOYAGES

The Oranje departed on its fourth voyage on 24 March, and once again Cynthia, Margaret Adams, Anne Jewell, Eva King, Mary McFarlane, Eileen Rutherford and Jenny Walker were on board. However, as the situation in the NEI had worsened, more Dutch staff had been obliged to leave the Oranje to be replaced by Australians and New Zealanders, including an eighth AANS nurse, Staff Nurse Nell Savage.

This time the ship sailed across the southern Indian Ocean to Durban, South Africa, and thereafter to Simonstown to go into drydock for a period. This afforded Cynthia and the others some time off for sightseeing. In due course they embarked once again and sailed up the east African coast to Port Tewfik, where they took on more than 680 patients. The return journey was uneventful, but just after the Oranje passed through Sydney Heads on its way to Wellington it had a close shave with Japanese submarines. The voyage concluded on 3 June with the ship’s return to Sydney. During the voyage, Cynthia had been promoted to the rank of sister, effective 15 May.

Cynthia’s third voyage – the Oranje’s fifth – took place from 6 November to 7 December. Evacuation practice began immediately upon departure and all procedures were tested and tightened. Cynthia and her colleagues worked in their wards, attended parades, and in their spare time swam in the ship’s pool, played deck sports and relaxed. When the ship arrived at Aden on 20 November the staff were informed that they would be transporting Allied casualties from the Desert War against Rommel from Port Tewfik to Durban in South Africa. Cynthia would not be returning to Australia for some time.

Embarkation of the patients at Port Tewfik took place on 27 November. Many appeared to have come straight from the battlefield and were in a pitiful state. The 644 patients, among them British, South African and various other Allied personnel, were quiet and subdued, quite unlike the rowdy Australian patients of previous voyages. The Oranje reached Durban after a short voyage down the east African coast and disembarked the patients.

The sixth voyage of the Oranje – Cynthia’s fourth – officially began upon its departure from Durban on 11 December. The ship sailed to Port Tewfik via Aden and arrived on 22 December. To their great delight, staff were given leave in the port, and some of the nurses managed to travel nearly to Cairo. The following day a further 632 British and Allied casualties were embarked, and at 3.00 pm the Oranje departed for Durban once again.

During the voyage to Durban, Christmas was celebrated, and following a very quiet New Year’s Eve, the Oranje arrived in port on 1 January 1943. Following disembarkation, the nurses were taken to hotels in the city, as the ship was going into dry dock to have its hull scraped. During this period several nurses, including Cynthia, travelled to Oribi Military Hospital in Pietermaritzburg, where most of the British and Allied patients from the previous voyage had been taken.

Cynthia’s fifth voyage – the Oranje’s seventh – began on 6 January. From Durban the ship sailed directly to Port Tewfik, arriving on 16 January. The following day 644 Australian and New Zealand patients were embarked, and that afternoon the Oranje departed. As it sailed down the Red Sea, it passed the Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth, on their way to Tewfik.

The Oranje was instructed to sail directly to Wellington, bypassing Australia altogether. It arrived outside Wellington Harbour on 5 February but was delayed by a thick fog and did not berth until the afternoon. Cynthia and the others spent 16 nights in New Zealand. After the New Zealand patients were disembarked, the Australian nurses were permitted day leave. They escorted – or were escorted by – their walking patients to picnics, dances, lunches and dinners. Some of Cynthia’s colleagues, among them Margaret Adams, enjoyed a trip to the snow.

Towards the end of February, the Oranje departed Wellington, and as it slid out of the harbour, a band on the wharf played ‘The Māori Farewell’. After stops at Adelaide and Melbourne, the ship arrived in Sydney at 8.00 am on 1 March.

THE CENTAUR

The Oranje’s return to Sydney marked the end of Australian involvement with the ship. Australian medical staff were urgently needed in Australia and New Guinea due to the growing Japanese threat and were withdrawn, to be replaced by New Zealanders, and the Oranje was relocated to the Middle East and Mediterranean. However, within a fortnight, most of the Australian staff, including Cynthia and her seven AANS colleagues, were reassigned to another hospital ship, the Centaur.

MV Centaur was built in Scotland in 1924 and arrived in Australia that same year to ply a route between Fremantle and Singapore. In 1940 the ship was placed under the control of the British Admiralty but continued its normal operations. At the start of 1943, following a request for a ship capable of serving in shallow southeast Asian waters as a hospital ship, the Centaur was loaned to the Australian government. It was converted in Melbourne and commissioned in March as 2/3rd Australian Hospital Ship Centaur.

On 12 March the Centaur set out from Melbourne to Sydney on a trial run. Numerous deficiencies were identified during the voyage, and the ship stayed in Sydney while they were being rectified. On 17 March Cynthia and the other Oranje nurses boarded the ship alongside four new colleagues – Sisters Myrle Moston, Alice O’Donnell, Edna Shaw and Joyce Wyllie.

The Centaur resumed its trial run on the morning of 21 March, when it departed for Brisbane. It arrived on 23 March and sailed again on 1 April for Townsville. Here Australian casualties repatriated from New Guinea were embarked, transported to Brisbane, and on 7 April disembarked at Newstead Wharf.

For the final leg of the trial, the Centaur sailed from Brisbane to Port Moresby with medical personnel and returned with Australian and American wounded, along with several wounded Japanese prisoners of war. It reached Brisbane on 18 April. Notwithstanding the fact that the ship’s officer in charge, Lt. Col. C. Hanson, subsequently pointed to certain deficiencies in rafts and emergency equipment, the Centaur’s effectiveness as a hospital ship had now been demonstrated.

CYNTHIA’S SECOND LETTER

Having returned home once again, Cynthia wrote to a friend in Hay describing her latter voyages on the Oranje and her first voyages on the Centaur. Just a few weeks later, following a tragedy that shook the whole country, her letter was published in The Riverine Grazier, as follows:

My Very Dear ‘Hay Mother,’ it was a thrill to get a letter from you yesterday. All the time I was on the Oranje, well over a year. I got very little mail, as it always seemed to be a lap behind – in the Middle East when we were at home, and vice versa.

We were lucky enough to have three trips to South Africa, one for docking and two carrying patients. You can just imagine how excited we were to hear that we would be taking the first British casualties from the Alamein battle to Durban. It was a new and very happy experience looking after men from famous regiments and especially the 51st Highland Division.

The Tommies and Jocks were quite a different proposition to our own Australians – much quieter and very shy. They were so used to discipline that even a ‘good morning’ from a sister brought them out of their beds and to attention. This state of affairs didn’t last long as we always treated the boys as patients first and soldiers afterwards. The majority of them were badly knocked about and out of a Ward of 45, I had 30 stretcher cases. But game! Not a complaint from one of them. Most of them were so tired that they slept most of the day, waking up only for meals and dressings. We were flat out from six in the morning until nine at night and only wished the day was twice as long.

Our second trip was much lighter as far as nursing was concerned, and we had more time to make friends with the boys, who this time included quite a number of South Africans. We had Christmas at sea and made up our minds to give the boys as nearly a home Christmas as possible.

Here the Red Cross turned up trumps. Mr. Clark, the representative on board, let us have pretty well anything we wanted. We made up about 700 stockings. We put in a pair of socks, a handkerchief, a packet of cigs. and some chocolate, with a bow of bright crinkle paper and round the packet. The night staff played Santy and weren’t the boys thrilled in the morning. We had been practising carols for a week before hand and on Christmas eve, beginning on the top deck at 9 p.m., worked our way all through the wards to the strains of Holy Night, Silent Night, Good King Wenceslas and all the old favourites. We carried torches covered with red paper, the result being most pleasing. In nearly every ward the patients joined in, so I think they really enjoyed it. I know that it was quite the happiest and most satisfying Christmas of my life.

I forgot to tell you about the Christmas dinner. The mess was decorated with bunting and streamers, with a large tree trimmed in the usual way with tinsel and coloured lights topped with a large silver star. Instead of using electric lights, there were coloured candles on the tables. The usual Christmas fare was served, but didn’t the lads cheer when blazing plum puddings were carried in. We had been saving up 3d bits for ages, and were able to collect about 300, so that most if not all the boys had something out of the pudding. My blind laddie was thrilled to find two in his helping – one that got there legitimately, and one that I had slipped on to his plate, just in case.

It was with real regret that we disembarked our boys, but as we were in Durban for a few days while the ship was getting her bottom scraped, we went to the military hospital at Pietermaritzburg, about 60 miles away, to see them settled in their new home.

The hospital is in a beautiful spot on a slight hill some miles out of the town itself – no traffic noises, no buildings surrounding it – just green fields and peace! What it must have meant to those poor lads you can just imagine. The nurses were mostly Canadian, but the V.A.’s were South Africans. The former wear a most attractive uniform of royal blue with a snowy apron on the bib of which is a large red cross. They all seemed such nice girls, smiling and eager to make the boys happy and comfortable. The ward for the blind boys, and I had one – a boy of twenty-one – was ideal. Round it was a garden of sweet scented flowers, with a little sunken lily pond at one end, where the boys used to dabble their feet on very hot days, much to their enjoyment, but to the detriment of the lilies, I’m afraid.

I’m terribly sorry that I will not be able to visit Pietermaritzburg again, particularly as it was there that I met Miss Edith Campbell. I’m sure you’ve heard of her – she was known as The Durban Signaller in the last war. I believe she met every troopship (Australian) that came to the port and entertained vast hordes of diggers. She still loves anything in a slouch hat and keeps open house for the Aussie sailors.

We went out to her home at Hilton for lunch where we met several lads from W.A., S.A. and Queensland. With great pride she took us to Two-up Tower, a huge cairn of stories which marks the spot in her garden where the old diggers played their national game, and where their sons still play it. We had afternoon tea in a summer house she calls Little Australia and where there are enough war souvenirs to crowd a museum. She keeps a large supply of Australian periodicals, and we saw the latest Bulletins and Smith’s Weeklies there. I asked her if she saw much difference between the Australian of today and his father of 25 years ago. But she said, ‘No,’ except that the lad of to-day always kissed her, whereas his father merely shook hands!

I was amused to hear of a picnic she arranged for some of our orderlies, who were a little doubtful as to the success of such a thing arranged by a little middle-aged lady. She arrived complete with car, packed them in and took them to a beautiful beach nearby for a surf, and when lunch time arrived, opened the boot of the bus – there were two dozen meat pies and a dozen bottles of beer! It was just exactly what the boys wanted and, ‘though she was a woman and a South African, at heart she was a Digger,’ they said, and nothing could have pleased her better.

Our home voyage was a most enjoyable one, lovely weather and a six weeks’ trip, as we went to New Zealand first and stayed there a fortnight. Even the sickest of the patients had improved out of sight with sea air, peace and good food. Every one was glad to be home again.

We were given a fortnight’s leave and told that our unit was to be disbanded. We were all very much upset as we had been very happy in our job and hated the thought of settling down to life ashore again. After ten days at home I was recalled to barracks and told that I along with most of the Australian staff of the ‘O’ had been appointed to the Centaur. She is a tiny little ship, about one-sixth the size of our luxury liner, but in spite of that she has been marvellously converted and very well equipped; she carries nearly half as many patients as the ‘O.’ We have done two trips already up north, and missed excitement up there [possibly the 12 April Japanese attack on Port Moresby] and by less than 24 hours, much to our disappointment. Still as things seem to be warming up, I daresay we will have all the active service we want…

THE FINAL VOYAGE OF THE CENTAUR

At 10.45 am on 12 May 1943, a little over three weeks after arriving back in Brisbane, the Centaur departed Sydney bound for New Guinea. The ship was tasked with transporting 193 members of the 2/12th Field Ambulance to Port Moresby and then embarking Australian casualties for repatriation. Among the medical staff on board that day were eight doctors, a pharmacist and the same 12 AANS nurses who had sailed on the previous voyage. As it happened, Cynthia had been unwell and need not have reported for duty that morning. Nevertheless, she did, and upon embarkation was instructed by Matron Jewell to go to the sickbay. She was still there when the Centaur set out.

On the evening of the 13 May, while the Centaur was off the northern New South Wales coast, a party was held for Matron Jewell, whose birthday it had been two days earlier. Arthur Waddington was the nurses’ steward and later described the party in a story published in The Australian Women’s Weekly:

Just a few hours before the torpedo hit I had seen those nurses so happy. The matron in charge of the nurses, Matron Ann Jewell, who went down with the ship, was celebrating her birthday with a party. The nurses had decorated the dining-table with flowers and everything looked very jolly. The party started at dinnertime and there was a lovely birthday cake for her. The nurses bought it in Sydney, and the ship’s cook iced it. It was white icing and had ‘Happy Birthday from the Centaur’ written in pink across it. I noticed that it wasn’t finished at dinner, and they took it to the main saloon to finish it off during the evening. Matron cut a slice for them all. A special menu was served that night, too. I meant to ask her the next day, just for a joke, just how old she really was. I was going to remark that there weren’t any candles on the cake, so was it meant to be a secret. I know she’d have enjoyed the joke.

Early the next morning, at 4.10 am, while most of those on board were asleep, a Japanese torpedo slammed into the hull of the Centaur. The ship exploded in a huge ball of fire and sank within three minutes. It had been passing North Stradbroke Island just off the southern Queensland coast.

Cynthia was among 268 people who lost their lives in the fireball or subsequently drowned. Ten of her AANS colleagues died with her. Of the nurses, only Nell Savage survived. She earned the George Medal for the courage and devotion to duty she demonstrated in the aftermath of the sinking.

After spending 35 hours in the water, 64 survivors were rescued by the American destroyer Mugford. Meanwhile, other ships continued the search. Among them was HMAS Lithgow – commanded through an incredible coincidence by Cynthia’s brother, Lt-Cmdr. Charles Haultain. He reeled in shock when he realised what had happened; he had exchanged greetings with his sister only a short while before the attack, when the Centaur had called into Brisbane.

The tragedy of the Centaur was felt deeply by all Australians and touched many personally. People felt outrage and grief in equal measure, and hundreds of memorial notices appeared in newspapers throughout the country.

In memory of Cynthia.

SOURCES

- BirtwhistleWiki, ‘102nd Australian Casualty Clearing Station.’

- COFEPOW (website), ‘A Journey to Holland on the Oranje 1947’.

- Goodman, R. (1992), Hospitals Ships, Boolarong Publications.

- Goossens, R., SS Maritime (website), ‘MS Oranje’.

- The History Buff (Campbelltown City Library Local Information Blog), ‘Sister Haultain’ by Claire Lynch (22 May 2019).

- Howlett, L. (1991), The Oranje Story, Oranje Hospital Ship Association.

- Milligan, C. and Foley, J. (1993), Australian Hospital Ship Centaur: The Myth of Immunity, Nairana Publications.

- Noonan’s of Mayfair, ‘A Collection of Medals to the Indian Police.’

- Young, N. (2020) via Virtual War Memorial Australia, ‘Mary Hamilton McFarlane.’

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS

- The Age (Melbourne, 14 May 1949, p. 11), ‘Family Notices.’

- The Argus (Melbourne, 1 Apr 1941, p. 4), ‘Dutch Gift Ship Here.’

- The Argus (Melbourne, 13 May 1944, p. 12), ‘Family Notices.’

- The Australian Women’s Weekly (29 May 1943, p. 9), ‘Men of Centaur Mourn Loss of Gallant Nurses.’

- The Australian Women’s Weekly (29 Jun 1946, p. 24), ‘Worth Reporting.’

- Camperdown Chronicle (25 May 1943, p. 4), ‘Around the District.’

- The Mercury (Hobart, 10 Sep 1941, p. 3), ‘Maiden Trip by Oranje as Hospital Ship.’

- Port Lincoln Times (21 Dec 1928, p. 3), ‘Religion and Education.’

- The Riverine Grazier (Hay, 7 Apr 1942, p. 1), ‘Letters From The Troops.’

- The Riverine Grazier (Hay, 21 May 1943, p. 2), ‘The Sinking of Centaur.’

- The Riverine Grazier (Hay, 28 May 1943, p. 2), ‘Christmas on a Hospital Ship.’