AANS │ Sister Group 1 │ Second World War │ Malaya │ 2/10th Australian General Hospital

Family Background

Caroline Mary Ennis was born on 13 August 1913 in Swan Hill, Victoria. She was the eldest child of Mary Josephine Carter (1888–1962) and Hugh Martin Ennis (1877–1922). Mary was from Balranald, near the Murray River in southern New South Wales. Hugh was from a large farming family and was born in Torrumbarry, near Echuca in Victoria.

Mary and Hugh were married on the morning of 30 October 1912 at St. Dympness’s Catholic Church in Balranald. After their wedding breakfast the happy couple set off on a motor journey to Swan Hill in Victoria and thereafter lived at ‘Ennisdale’, Hugh’s 638-acre leasehold property at Nowie, near Swan Hill.

In August 1913 Mary gave birth to Caroline at Nurse Wise’s Private Hospital (also known as Marada Private Hospital), on Beverage Street in Swan Hill. In December that year Hugh was successful in a selection ballot for more than 12,000 acres of the old Eurimpy Station, near Richmond in outback Queensland. In February 1914 he sold the property at Nowie, and the family moved to Queensland. In November Caroline’s brother, John Patrick (Jack) Ennis, was born.

In 1916 Hugh acquired a 12,300-acre selection known as ‘Wilyama’, not far from the Eurimpy property, and the family moved here. The following year Caroline’s sister Mary Josephine (Molly) Ennis was born.

In December 1921 Hugh underwent a serious operation at Charters Towers Hospital. While in hospital he sold ‘Wilyama’ to the owner of ‘Silver Hills’, an adjoining property, concluding the sale in January 1922 as he was recovering. Thereafter the family moved to Charters Towers and Hugh began to look for another property near Richmond.

However, after seemingly making a full recovery, Hugh died suddenly of septic pneumonia on 18 July in Charters Towers, possibly as a long-term consequence of the operation. His funeral, held the following day, left St. Columba’s Catholic Church on Gill Street.

Mary Ennis was left with eight-year-old Caroline, seven-year-old John, four-year-old Mary – and five-month-old Patricia, who had been born on 6 February that very year. Fortunately, Hugh left a substantial amount of money in his estate to be shared between his wife and his brother William, of ‘Blantyre’, near Richmond.

In 1924 Mary married Joseph Graham at St. Kilian’s Church in Bendigo, Victoria. Joseph, a farmer, was born in 1899 in Clermont, Queensland, and had 11 siblings. Mary, Joseph and the children moved to the parish of Little Billabong, near Gerogery, New South Wales, where in 1922 Joseph had taken out a 10-year lease on a 27-acre parcel of dairy and agricultural land. Here Caroline’s half-siblings Marjorie Maureen Graham (b. 1926) and James Joseph Graham (b. 1929) were born.

Nursing and enlistment

Following the birth of James, the family moved to Victoria, and in 1931 Theresa Gloria Graham was born. Shortly after Caroline, now nearly 19, decided to become a nurse, and in mid-1932 began to train at the Ovens District Hospital in Beechworth (also known as Beechworth Hospital). After passing her Nurses’ Board examination in March 1936, she completed her training in June and was granted her certificate in late July. She stayed at the hospital for the next four-and-a-half years.

By now the Ennis-Grahams were living at Cheshunt, in the King Valley in northeastern Victoria, where Caroline’s fourth and final half-sibling, Val Graham, was born. Also living in Cheshunt at the time were Dorothy and Robert Elmes, whose daughter Gwenda, known as Buddy, was nine months younger than Caroline and was training to be a nurse at Corowa Community Hospital, just over the border in New South Wales. In time, Buddy would share a fate as tragic as Caroline’s.

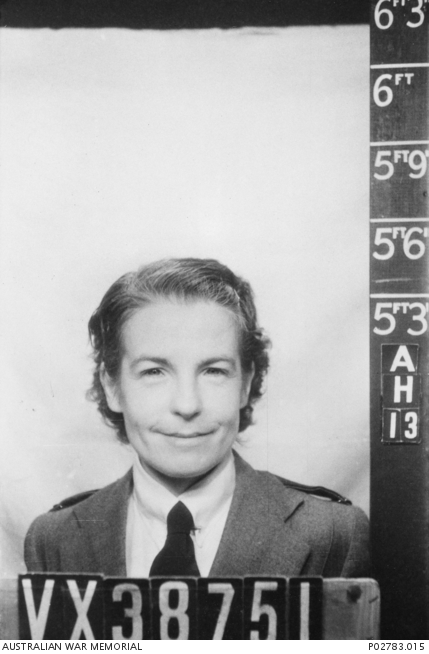

When war broke out, Caroline, like many of her peers, volunteered for service with the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS). On 20 August 1940 she filled out her Attestation Form for overseas service with Australia’s all-volunteer expeditionary force, the Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF), and was appointed to the AANS, 3rd Military District (Victoria). Buddy had volunteered too and was appointed to the AANS, 2nd Military District (New South Wales).

On 11 January 1941 Caroline was appointed at the rank of Staff Nurse to the 2/10th Australian General Hospital (AGH), a medical unit being raised at the Royal Agricultural Society Showground, over the road from Victoria Barracks, in Sydney. Fellow Victorians Ruby Freeman, Nesta James, Rene Singleton and Dot Paschke were also appointed to the 2/10th AGH that day – Dot as the unit’s matron.

The queen mary

The Victorian recruits were each granted leave without pay until 23 January followed by pre-embarkation leave. On 31 January they commenced duty with the 2/10th AGH and on 2 February boarded a train for Sydney, arriving the next day. They travelled to Darling Harbour and were taken by ferry to the Queen Mary, which was anchored off Bradley’s Point. The nurses boarded the famous ship alongside thousands of troops of the 22nd Brigade, 8th Division, 2nd AIF, known as ‘Elbow Force.’ Although their destination was as yet an official secret, they were set to sail to Malaya following a British request for Australian reinforcements to join British and Indian troops in garrisoning the British colonial possession.

Travelling with the troops and tasked with looking after them in Malaya were the 2/10th AGH, the 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station (CCS), the 2/9th Field Ambulance, and several smaller medical units. Only the 2/10th AGH and 2/4th CCS had AANS nurses on staff. Once on board, Caroline, Ruby, Nesta, Rene and Dot met their 38 new colleagues from New South Wales and Queensland and the six South Australian and Tasmanian nurses of the 2/4th CCS.

On 4 February, with all the troops now embarked, the Queen Mary weighed anchor and sailed out of Sydney Harbour. Once outside the Heads, the ship joined the Aquitania and the New Amsterdam, which were carrying Australian and New Zealand troops, respectively, to Bombay, from where they would transship for the Middle East. Together with their escort ship, the three mighty liners headed south. Several of the nurses later wrote of the beauty of their first night on the water, as the ships sped along under a silvery full moon. After a few days the Mauretania, having embarked from Melbourne, joined the convoy with more Australian troops.

The ships arrived at Fremantle on 10 February, and Caroline and her colleagues spent the day in Perth. When they set off again two days later, two more nurses of the 2/4th CCS had joined them. On 16 February, in the vicinity of Sunda Strait, the Queen Mary swung to port, circled behind the other ships, and then charged past them, headed for Malaya – thus confirming a destination only announced officially a short time before but long rumoured. Two days later, Caroline and the others arrived at Sembawang Naval Base on the north coast of Singapore Island.

Malacca

The nurses disembarked and were taken to adjacent railway sidings. They gave their names and addresses, were issued with rations, and then entrained for the Malay Peninsula. The 2/10th AGH nurses alighted at Tampin, while the 2/4th CCS nurses continued to Seremban, further north.

From Tampin Caroline and her colleagues were driven to Malacca. The 2/10th AGH had been allocated several wings of the town’s Colonial Service Hospital, a modern, five-storey building set in spacious grounds some way out of town. The nurses were quartered on the fourth floor of one of the wings.

Initially the heat was enervating, but the nurses soon grew accustomed to it and began to feel at home. They were kept busy looking after around 400 patients a month, mainly cases of tropical infection and disease, as well as accidental injuries and routine operations, but had housemaids (known as amahs) to do their housework and had plenty of time for such off-duty activities as shopping, golf, tennis and swimming, dancing, Sampan picnics, and chicken-suppers on the beach. They were made honorary members of European-only clubs. They visited tin and gold mines and rubber estates and were taken on long drives through the delightfully verdant countryside.

On Leave

The nurses were granted several periods of leave across the year, during which they could visit Singapore, Kuala Lumpur and Fraser’s Hill, a hill station in the cool highlands north of Kuala Lumpur. Caroline went on leave from 29 to 31 May and from 12 to 14 June.

On 19 July Caroline and Rene Singleton were detached to the 2/9th Field Ambulance, which was based at Port Dickson, on the coast north of Malacca, and where the nurses of the 2/4th CCS had earlier established a 50-bed dressing station. The dressing station would function as a first-aid post for the three 8th Division battalions, which were encamped in the Port Dickson–Seremban area. More serious cases would go to the 2/4h CCS at Kajang or to the 2/10th AGH.

During her time at Port Dickson, Caroline was granted leave from 30 July to 3 August and spent it at Fraser’s Hill. She went with Jessie Blanch, Flo Trotter and Iva Grigg, who picked her up from Seremban. Jessie Blanch described the trip in her diary.

Up bright and early to go to Fraser’s Hill. Trotter, Grigg and self. Left by military car at 7 am for the station, caught the 18 mins past 7 train, nice trip up. Picked Ennis up at Seremban. Arrived at Kuala Lumpur at about 11.30 am, met by military car and taken to see the sights. Had lunch and then left for Fraser’s Hill at 12.30 pm. Had lovely trip up – a lot of corners but we weren’t sick. Arrived at the Hill about 3.30 pm, met by the 4 who were coming home. Very cool, have to wear a cardigan. Went for a walk and went to bed early after a luscious dinner. Two blankets on (Kirkland, p. 15).

Caroline returned to Malacca on 1 September. Shortly after, or perhaps while she was still at Port Dickson, she wrote a (signing off as “Carol”) to the Sun News-Pictorial in Melbourne to thank readers of its ‘Here, There and Everywhere’ column for sending copies of the Sun and other reading matter to her through the ‘Diana’s Send-a-Sun Scheme’, which began in early 1940. Her letter was published on 17 September, as follows:

At regular intervals since I have been abroad, bundles of papers and other welcome reading matter have reached me from one who signs herself my Sun Sender. In each bundle of papers there is always some useful gift which is very much appreciated. l would like to thank my Sun Sender, through you, and let her know that her kindness is appreciated by me and also by those to whom I pass the papers on.

The War Clouds Gather

By then a second AGH, the 2/13th, with a staff of 49 AANS nurses and some 175 officers and men, had arrived at Singapore Island aboard the AHS Wanganella and was based at St. Patrick’s School at Katong on the south coast of Singapore Island. The unit been raised in Melbourne in early August following a request from Colonel Alfred P. Derham, the commanding officer of 8th Division medical services in Malaya, who felt that a second military hospital was urgently needed in view of intelligence reports suggesting the possibility of a Japanese invasion.

Fears of Japanese aggression had grown steadily across the year, and by November all the signs in the international arena pointed to war. By the end of that month Commonwealth forces in Malaya were advanced to the second degree of readiness, which meant that leave was cancelled, and units had to be ready to move at a few hours’ notice to their areas of deployment. Then, on 4 December, the codeword ‘Raffles’ was given, indicating advancement to the first degree of readiness. War was imminent.

It came on 8 December, when just after midnight a force of some 5,000 troops of the Imperial Japanese Army launched an amphibious assault at Kota Bharu on the Malay Peninsula’s northern coast. Four hours later, 17 Japanese bombers attacked Singapore Island.

Japanese invasion

Japanese infantry, backed by mechanized units and substantial sea and air power, surged down the Malay Peninsula in three lines of attack at a steady pace of 15 kilometres a day, forcing severely outgunned British and Indian troops to retreat southwards, and by 29 December it had become clear that the 2/10th AGH would have to evacuate from the Colonial Service Hospital.

Colonel Derham decided to move the hospital to Singapore Island but would need time to organise a suitable site. In the meantime, the 2/10th AGH’s personnel and patients moved south in stages. Between 29 December and 5 January 1942, 36 nurses and around 40 other staff were detached to the 2/13th AGH, which was now based in a psychiatric hospital in Tampoi in the southern Malay Peninsula. Scores of patients were moved at the same time.

On 6 January, 20 more 2/10th AGH nurses, including Caroline and Matron Dot Paschke, were detached to the 2/4th CCS, which had by now moved to the Mengkibol Estate, a rubber plantation five kilometres to the west of Kluang. On 13 January, Matron Paschke left Mengkibol with the CO of the 2/10th AGH, Colonel Edward Rowden White, to inspect the site chosen on Singapore Island for the unit’s occupation – Oldham Hall, a Methodist boarding school at Bukit Timah, around 8 kilometres north of Keppel Harbour. By 15 January the unit had completed its relocation.

In the meantime, on 14 January Australian 8th Division troops had entered combat for the first time. They scored a tactical victory against a Japanese force near the town of Gemas, in northern Johor, but the following day a much bloodier battle was fought, and that night convoys of Australian casualties flowed to Caroline and the others at Mengkibol. Japanese troops continued to press southwards virtually unopposed.

Caroline rejoined her unit at Oldham Hall on 17 January, as had most of the detached nurses by now. Eight days later, the 2/13th AGH completed its own move back to Singapore Island. On 28 January it was turn of the 2/4th CCS to evacuate to Singapore Island, relocating to Bukit Panjang English School. Then, on the night of 30 January, the final Commonwealth troops crossed the Causeway from the peninsula to the island. The next morning it was blown up. Soon after, the Japanese forces reached the northern shore of Johor Strait and on 2 February began a ferocious artillery bombardment of the island. The final battle was about to begin.

the final days

When Japanese soldiers began to cross Johor Strait on the night of 8 February, the end was nigh. By the morning, they had established a beachhead on the northwestern corner of Singapore island, despite strong opposition from Australian troops. The heavy fighting produced many casualties, and at Oldham Hall the wards became so overcrowded that men were lying on mattresses on the floor while others waited outside. Operating theatre staff worked around the clock, treating severe head, thoracic and abdominal injuries. There was little respite for staff when off duty either, as the constant pounding of bombs and shells meant that sleep was hard to come by.

With Singapore’s fate all but certain, a decision was made to evacuate the nurses. Already in January, following reports of Japanese atrocities in Hong Kong, Colonel Derham had asked Major General H. Gordon Bennett, commanding officer of the 8th Division in Malaya, to evacuate the AANS nurses. Bennett had refused, citing the damaging effect on morale. Colonel Derham then instructed his deputy Lt. Colonel Glyn White to send as many nurses as he could with Australian casualties leaving Singapore.

The nurses’ pleas to be allowed to stay with their patients were ignored, and on 10 February, six of Caroline’s 2/10th AGH colleagues embarked with 300 wounded Australian soldiers on the makeshift hospital ship Wusueh. The following day a further 60 AANS nurses, 30 from each AGH, left on the Empire Star.

Vyner Brooke

Sixty-five AANS nurses remained in Singapore, among them Caroline. On Thursday 12 February they too were ordered to leave. Late in the afternoon they were driven by ambulance to St. Andrew’s Cathedral, where they were joined by the remaining nurses of the 2/13th AGH and the 2/4th CCS. From the cathedral the ambulances proceeded towards Keppel Harbour until they could go no further, at which point the nurses got out and walked the remaining few hundred metres.

At the wharves Caroline and her 64 comrades were ferried out to a small coastal steamer, the Vyner Brooke, lying at anchor in the harbour. On board already there were as many as 150 people – women, children, and old and infirm men. As darkness fell, the Vyner Brooke slipped out of Keppel Harbour and eventually began its journey south. Behind it, the Singapore waterfront burned, and thick black smoke rose into the sky.

That night the Vyner Brooke made little progress and spent much of Friday hiding among the hundreds of small islands that line the passage between Singapore and Batavia. By the morning of Saturday 14 February, Captain Borton was approaching the entrance to Bangka Strait. To the right lay Sumatra; to the left, Bangka Island.

Suddenly, at around 11.00 am, a Japanese plane swooped over, then flew off again. At around 2.00 pm another plane approached before flying off. The captain, anticipating the imminent arrival of Japanese dive-bombers, sounded the ship’s siren and began a run through open water. When a squadron of dive-bombers appeared on the horizon, Borton commenced evasive manoeuvres. As the bombers approached, the Vyner Brooke zigzagged wildly at full speed. After many near misses, a bomb inevitably struck the forward deck, killing a gun crew. Another entered the funnel and exploded in the engine room, causing the ship to lift and rock with a vast roar. A third tore a hole in the side. The Vyner Brooke listed to starboard and began to sink. It was 15 kilometres from Bangka Island.

Caroline’s 2/10th AGH colleague Betty Jeffrey was with her when the bombs struck. She described the tragic aftermath in her book White Coolies (pp. 6–11):

We had been given instructions that morning what the drill was to be if we were bombed or torpedoed. Different jobs were allotted to each nurse. Now everyone hurried about the decks doing the task assigned to her.

We were all carrying morphia, field dressings, and extra dressings we had made on board. Sister Ennis and I made a beeline for the bridge, being last down into the lounge. Taking a child each with us, we were first out. We left the children with an Englishwoman and dashed towards the bridge, only to find it was an unrecognisable mess and burning fiercely. I grabbed a Malay sailor and put my inadequate field dressing on the worst part of burns on his leg. It was an emergency dressing I had brought all the way from Melbourne and carried around Malaya for nine months!

[…]

We had been told to see that every civilian person was off the ship before leaving it ourselves. Believe me, we didn’t waste time getting them overboard. Nobody was anxious to linger on a burning and rapidly sinking ship.

[…]

Beth Cuthbertson searched the ship when it was at a very odd angle to make sure all wounded people had been taken off and that nobody remained, while other nurses were busy getting people into the sea.

At this stage there were quite a few people in the water … and the ship was listing heavily to starboard. The oldest people, the wounded, Matron Drummond, and some of our girls with all the first aid equipment, were put into the remaining lifeboats on the starboard side and lowered into the sea. Two boats got away safely. Greatcoats and rugs were thrown down into them and with bright calls of “See you later!” they rowed away. The last I saw of them, some sisters were frantically bailing out water with their steel helmets.

The third boat was caught by the ship when she started to roll on her side and so had to be evacuated very smartly.

Matron Paschke set a superb example to us all by the calm way in which she organised the evacuation of the ship. As the Australian sisters went over the side, she said, “We’ll all meet on the shore girls and get teed up again.”

It was our turn. “Take off your shoes and get over the side as quickly as you can!” came the order. Off came our shoes … and we all got busy getting over.

[…]

Land was just visible, a big hill jutting up out of the sea about 10 miles away.

I had been so busy helping people over the side that I had to go in a very big hurry myself. Couldn’t find a rope ladder, so tried to be Tarzan and slip down a rope. …

… The coolness of the water was marvellous after the heat of the ship. We all swam well away from her and grabbed anything that floated and hung on to it in small groups. We hopelessly watched the Vyner Brooke take her last roll and disappear under the waves. I looked at my watch – 20 to three. … Then up came oil – that awful, horrible oil, ugh!

I was swimming from group to group looking for Matron Paschke … when I saw a raft packed with people and more grey uniforms. There was Matron, clinging to this crowded thing. She was terribly pleased with herself for having kept afloat for three hours …

On this raft were two Malay sailors, one a bit burnt, who were ineffectively trying to paddle the thing, but had no idea how. Sister Ennis was holding two small children, a Chinese boy aged four and a little English girl about three years of age. There were four or five civilian women and Sisters Harper, Trenerry, and McDonald from the 13th AGH, Sister Dorsch from the 2/4 CCS, and Matron Paschke and Sisters Ennis, Clarke, and myself from the 2/10 AGH. There seemed no hope of being picked up, so we tried to organise things a little better. Our oars were two small pieces of wood from a packing case and nobody seemed to be able to use them to effect, so more rearranging was done. Those who were able hung on to the sides of the raft, those who were hurt or ill sat on it, while Matron, Iole Harper, and I rowed all night long in turn. …

We seemed to pass, or be passed by, many of the sisters in small groups on wreckage or rafts. Everybody appeared to be gradually making slow progress towards the shore, and every one of us felt quite sure she would eventually get in.

… We eventually came in close to a long pier, but were carried out to sea again. We saw a fire on the shore, and knew the lifeboats had made it, so we paddled furiously to get there. We gradually got nearer and nearer and saw the girls, even heard them talking, but they could neither hear nor see us because of a storm, which took us out to sea again. … We seemed helpless against those vile currents. …

The two small children with us were very good and they slept most of the time in Sister Ennis’s arms. It was very rough and dark and we rocked and tossed until everybody was sick. During the storm the little girl awakened and her tiny voice said. ‘Auntie, I want to go upstairs.’ Poor little soul, she was absolutely saturated with salt water, but Ennis had to take off her pants before she was convinced that it would be all right. Those two children behaved extremely well, cried very little, and were certainly no trouble.

[…]

When daylight came we were all very tired and just as far out to sea as we were when bombed, but miles further down the coast …

As we were not getting anywhere and the load was far too heavy, the two Malays, Iole Harper, and I left the raft to swim alongside and so lighten the load. My hands were badly cut about now and too swollen to even cling to the ropes, also we were too tired to row any longer. Two other Sisters took over, and at last we made progress. We were all coming in well, we four swimming alongside and keeping up a bright conversation about what we’d do and drink when we got in – then suddenly the raft was once more caught in a current which missed us and carried them swiftly out to sea. They called to us, but we didn’t have a hope of getting back to it: they were travelling too fast for us to catch them. And so we were left there.

We didn’t see Matron Paschke and those Sisters again. They were wonderful.

Caroline was one of 12 nurses to be lost at sea following the sinking of the Vyner Brooke. Of the 53 who made it ashore, 21 were murdered by Japanese soldiers. The surviving 32 were subsequently imprisoned for three-and-a-half years. Only 24 came home.

In memoriam

On 8 March 1959 two ash trees were planted outside Cheshunt Hall, one in memory of Caroline, the other of Buddy Elmes, each with a memorial plaque in front of it. Caroline’s tree was replaced with a claret ash in September 2024 after beginning to perish.

Caroline is also memorialised on the Roll of Honour at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra; with Buddy Elmes on a memorial plaque mounted at Wangaratta Hospital; on the Singapore Memorial at the Kranji War Cemetery in Singapore; and in many other places.

As of 26 October 2025, bronze busts of Caroline and Buddy Elmes were being cast. They will be mounted in the town of Oxley, 10 kilometres south of Wangaratta.

In memory of Caroline.

Sources

- Ancestry.

- Australian War Memorial, ‘The Last Post Ceremony commemorating the service of Sister Caroline Mary Ennis, 10th Australian General Hospital, Australian Army Nursing Service, Second World War’ (8 May 2018).

- Jeffrey, B. (1954), White Coolies, Angus & Robertson.

- Kirkland, I. (2012), Blanchie: Alstonville’s Inspirational World War II Nurse, Alstonville Plateau Historical Society Inc.

- National Archives of Australia.

- Northeast Health Wangaratta, ‘Nurses from WWII.’

- Places of Pride, National Register of War Memorials, an initiative of the Australian War Memorial, ‘Sister Dorothy Elmes & Sister Caroline Ennis Memorial.’

- Shaw, I. W. (2010), On Radji Beach, Pan Macmillan Australia.

- Virtual War Memorial Australia, ‘Caroline Mary Ennis.’

Sources: Newspapers

- The Albury Banner and Wodonga Express (21 Apr 1922, p. 41) ‘Granting of Special Lease.’

- The Brisbane Courier (9 Dec 1913, p. eight), ‘Land Commissioners’ Courts.’

- The Daily Mail (Brisbane, 11 Aug 1922, p. 13), ‘News from the Country.’

- The Daily Mail (Brisbane, 4 Jan 1922, p. 9), ‘News from the Country.’

- The Northern Miner (Charters Towers, 19 Jul 1922, p. 2), ‘Family Notices.’

- The Northern Miner (Charters Towers, 22 Jul 1922, p. 3), ‘Telegrams Queensland.’

- Ovens and Murray Advertiser (Beechworth, 25 Jul 1936, p. 1), ‘Ovens District Hospital.’

- Riverina Recorder (Balranald, 6 Nov 1912, p. 2), ‘Wedding.’

- Riverina Recorder (Balranald, 1 Oct 1913, p. 2), ‘Family Notices.’

- The Sun (Sydney, 1 Mar 1954, p. 14), ‘Ordeal in Malaya: Army Nurse’s Diary of Horror and Heroism.’

- The Sun News-Pictorial (Melbourne, 17 Sept 1941, p. 7), ‘Here, There & Everywhere.’

- The Sun News-Pictorial (Melbourne, 16 April 1948, p. 10), ‘Nurse’s Memory.’

- Swan Hill Guardian and Lake Boga Advocate (26 Jan 1914, p. 2), ‘Auction Sales.’

- Swan Hill Guardian and Lake Boga Advocate (2 Feb 1914, p. 3), ‘Advertising.’

- Wangaratta Chronicle (26 Oct 2025, web edition), ‘Bronze busts are underway for slain nurses.’