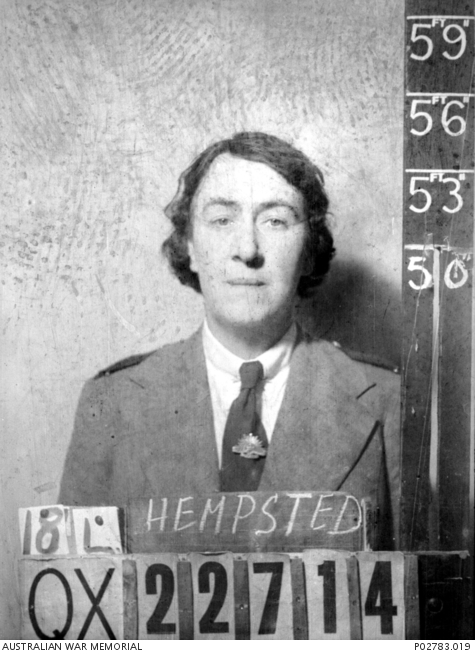

AANS │ Captain │ Second World War │ Malaya │ 2/13th Australian General Hospital

FAMILY BACKGROUND

Pauline Blanche Hempsted, known as Blanche, was born on 9 September 1908 on Alfred Street in Fortitude Valley, Brisbane. She was the daughter of Bertha Louisa Howard (1883–1959) and Percy Hempsted (1877–1942), both of whom were born in Brisbane.

Percy lived in Spring Hill, immediately north of the Brisbane city centre. He was the son of John Hempsted, who had migrated from England in the 1860s and established an aeration and bottling business in Brisbane that eventually became Hempsted’s cordial factory. On 30 December 1896 Percy was working at the factory when he suffered a dreadful accident. While adjusting a belt, he was drawn onto the shaft of the machinery and had his right arm severed at the elbow. Bertha, meanwhile, lived with her family in Fortitude Valley, a suburb bordering Spring Hill. In 1906 she appeared several times on stage with the Brisbane Variety Entertainers.

Percy overcame his misfortune and on 1 August 1906 married Bertha. The wedding took place at All Saints’ Church on Wickham Terrace in Brisbane city. The happy couple settled in Fortitude Valley, and two years later Blanche was born.

By October 1912 the family had moved to Verney Road in Graceville in south Brisbane. Here, in May 1914, Blanche’s baby brother, Claude Howard Hempsted, came into the world.

SCHOOLING

Blanche attended St. Catharine’s Church of England Girls’ School in Stanthorpe, a town 200 kilometres southwest of Brisbane. On 6 November 1920 the school held an art exhibition to raise funds towards the building of St. Martin’s War Memorial Hospital in Brisbane (which today houses the offices of the Anglican diocesan administration). Blanche was awarded one of three prizes in the ‘Maps’ section.

In 1922 Blanche, now 13, started at St. Margaret’s School, an Anglican girls’ school in Albion, an inner northern suburb of Brisbane. At the end of 1923, at the school’s annual prize-giving ceremony, Blanche was one of four awardees in Form Lower V of the ‘general average’ prize. After the prizes were distributed the Archbishop of Brisbane addressed the girls, congratulating them on their year’s work.

Blanche finished school at the end of 1924 and the following year joined the St. Margaret’s Old Girls’ Association. On 21 April she attended a social evening at St. Margaret House in Clayfield held to welcome around 35 new members of the association.

Just two months later, on 10 June, the family suffered a tragedy when Claude Hempsted fell under a moving train at Central Station, Brisbane, and was killed. He had been returning home after school with his schoolmates, and as the train to Oxley drew into the station, he ran along the platform and attempted to open a door to one of the carriages. He tripped and fell between that carriage and the one behind. He was identified by his father.

Blanche moved in social circles whose members’ activities featured regularly in the society pages of the newspapers. From 1926 until 1934 she attended numerous dances and balls, very often held to raise funds for such worthy causes as the St. Albans Memorial Church in Auchenflower, the piano fund of the Seamen’s Institute, and the humanitarian circle of the Town and Country Women’s Club. Many of the fundraisers were held in aid of the St. Margaret’s School building fund, such as a concert, as part of which Blanche appeared in a playlet, ‘The Prince Who Was a Piper.’ Aside from fundraising events, Blanche was invited to going-away parties and bridge parties, shower afternoons, afternoon teas and pre-wedding suppers. On 14 April 1932, she was one of the bridesmaids at the wedding of her friend Sybil Holliman and was a bridesmaid again in March 1934.

NURSING

Eventually Blanche decided upon a career in nursing and from 1934 to 1938 trained at Brisbane General Hospital. Among the trainees at Brisbane at that time were several with whom Blanche would later serve in Malaya – Sylvia Muir from Longreach and Phyllis Pugh from Brisbane in her own unit, the 2/13th Australian General Hospital (AGH), and Jessie Blanch, Pearl Mittelheuser, Flo Trotter and Joyce Tweddell in a sister unit, the 2/10th AGH.

In mid-January 1940, having gained her certificate in general nursing, Blanche was appointed to the staff of Collinsville Hospital in the Whitsunday region of north Queensland. In early April she requested three weeks’ leave to return to Brisbane to visit her fiancé, who had enlisted in the Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF) and was about to embark for overseas. Due to staffing concerns, however, her application was not approved, and she resigned. Following a board meeting, her leave was approved retrospectively, and she returned to Collinsville after her visit. Towards the end of the year, Blanche resigned for good and left for Brisbane on 6 November. She was going to volunteer for war service.

ENLISTMENT

Back in Brisbane, Blanche applied to join the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS). Her application was accepted, and on 6 April 1940 she was appointed to the AANS, Northern Command (Queensland). After waiting a year, on 27 April 1941 Blanche was called up for full-time domestic duty with the Australian Military Forces (AMF) and posted to the 112th AGH at Bowen Hills, an inner suburb of Brisbane immediately north of Fortitude Valley.

The 112th AGH had been formed two days earlier at the Exhibition Grounds at Bowen Hills. It then moved to a small and cramped site at the Kangaroo Point Immigration Depot (after the war known as ‘Yungaba’). The hospital mainly treated patients from those AMF units training or based in Brisbane. Joining Blanche at the hospital was a nurse by the name of Val Smith, from Wondecla in northern Queensland, who, like Sylvia Muir and Phyllis Pugh, would serve with Blanche in the 2/13th AGH in Malaya.

Blanche ceased full-time duty with the AMF on 3 August and the following day was seconded to the 2nd Australian Imperial Force (AIF) for overseas duty with the AANS. She was assigned the rank of sister and remained with the 112th AGH, which by then had moved to the Kangaroo Point site. Val was seconded to the 2nd AIF in mid-August. Two more nurses appointed to the 2nd AIF with whom Blanche and Val would serve had also arrived at Kangaroo Point, Vi McElnea from Ingham and Myrtle McDonald from Wowan, near Rockhampton.

Around mid-August Blanche and her new colleagues were advised that they would shortly be attached to a medical unit and to prepare for embarkation. They were sent on leave and on 27 August were attached to the 2/13th AGH. The unit had been raised in Melbourne in early August following a request from Col. Alfred P. Derham, the commanding officer of 8th Division medical services in Malaya, who felt that a second military hospital was urgently needed in view of intelligence reports suggesting the possibility of a Japanese invasion. The 2/13th AGH would join the 2/10th AGH and the 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station (CCS), which had sailed to Malaya on the Queen Mary in February that year with nearly 6,000 troops of the 22nd Infantry Brigade, 8th Division.

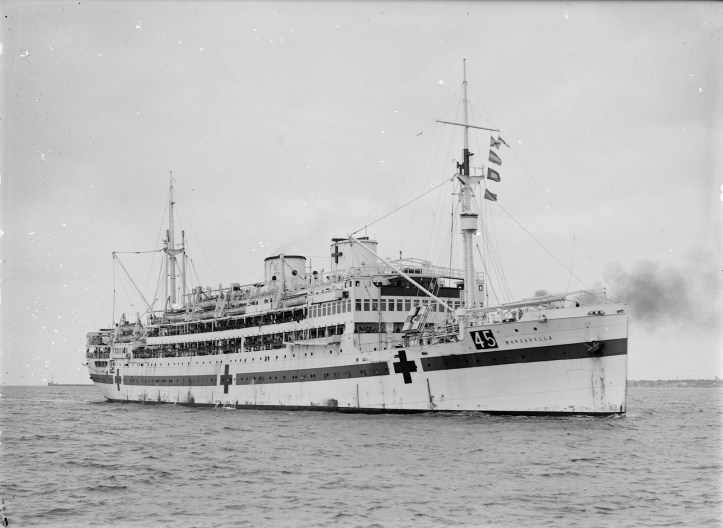

AHS WANGANELLA

On 28 August Blanche, Val, Vi and Myrtle, together with Sylvia Muir, Phyllis Pugh, Eileen Short from Maryborough, Margaret Selwood from Brisbane, and Julia Powell from Blackall, who oversaw the Queensland contingent, met at Brisbane Central Station and entrained for Sydney. They arrived the following day and proceeded to the harbour, where they boarded the 2/2nd Australian Hospital Ship Wanganella. They were joined on board by a New South Wales 2/13th AGH contingent led by Sister Marie Hurley.

On 30 August the Wanganella departed for Melbourne, where a further 24 Victorian, South Australian and Tasmanian AANS nurses and around 180 other 2/13th AGH personnel embarked. After seven more nurses joined in Fremantle, the unit had a strength of 49 AANS nurses.

Shortly after leaving Fremantle those aboard the Wanganella were officially told that they were going to Malaya. Many had expected to be going to the Middle East and feared that they would not see action in Malaya. They could not have been more mistaken.

MALAYA

On 15 September, the Wanganella berthed at Victoria Dock on Singapore Island, and Blanche and her new colleagues disembarked. Ten were detached immediately to the 2/10th AGH, which had established its hospital in Malacca, on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula. There, the 2/13th AGH nurses would learn tropical nursing from their experienced colleagues – knowledge they would then bring back to the 2/13th AGH. Over the next three months, most of the 2/13th AGH nurses would be rotated through either the 2/10th AGH or the 2/4th CCS, which at the time was based in an unfinished psychiatric hospital in Tampoi, in the south of the Malay Peninsula.

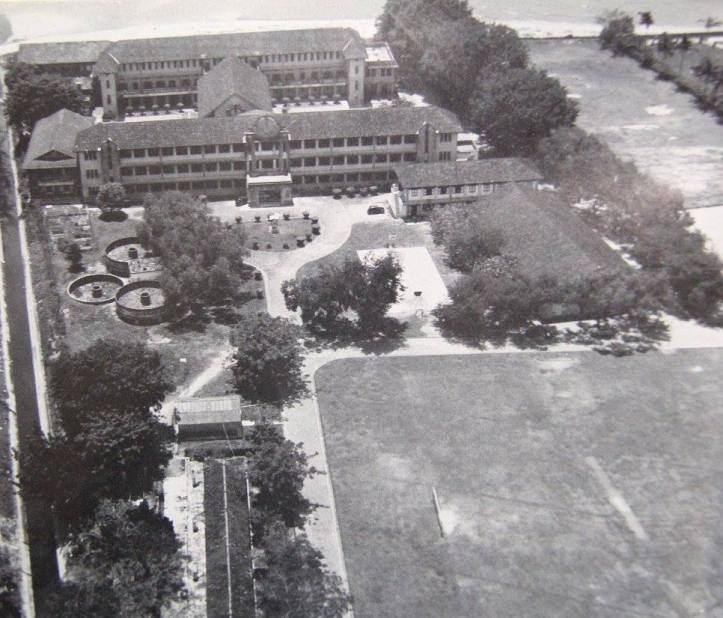

Meanwhile, Blanche and the others were taken to St. Patrick’s School, located in Katong on the south coast of Singapore Island. Here, the unit would be billeted while it waited to be sent to its permanent base, the psychiatric hospital in Tampoi currently occupied by the 2/4th CCS.

St. Patrick’s School was set in large, lush grounds and consisted of several brick buildings. The nurses’ quarters were comfortable, but the humidity was oppressive. In the absence of applied nursing work, Blanche and her colleagues attended lectures in tropical nursing, diseases and other related topics, and were taken on field visits to various civilian hospitals on the island. They also had plenty of free time for socializing, shopping and sport.

From 14 October to 23 November, Blanche, Val, Vi and Eileen Short were among a cohort of 2/13th AGH nurses detached to the 2/4th CCS at Tampoi. Sylvia Muir joined them on 11 November. The 2/4th CCS had set up a small hospital of 150–200 beds inside the rambling, single-story complex of concrete buildings leased from the Sultan of Johor and set on the edge of the jungle. The nurses’ quarters were located more than a kilometre from the hospital, and they were driven to and fro in battered little buses.

Around 20 November the 2/13th AGH finally received orders to proceed to Tampoi. By 23 November it had taken over the site from the 2/4th CCS, which moved north to Kluang, and Blanche and the others rejoined their unit. It was something of a challenge to bring the hospital up to speed, but between the nurses and the orderlies they soon managed to have a functioning hospital of some 600 beds.

INVASION

Blanche’s pleasant life in Malaya was turned upside down two weeks later, when Japan invaded. Soon after midnight on 8 December, a force of some 5,000 troops of the Imperial Japanese Army launched an amphibious assault at Kota Bharu on the Malay Peninsula’s northern coast. Four hours later, 17 Japanese bombers attacked Singapore Island. The planes could be heard droning overhead from Tampoi – as could the distant explosions.

Japanese forces swept through the Malay Peninsula, comprehensively brushing aside British, Indian and Australian troops. By mid-January the 2/10th AGH had been evacuated to Singapore Island, followed by the 2/13th AGH and finally the 2/4th CCS. By 1 February all Commonwealth troops had withdrawn to the island and the causeway linking it to the peninsula had been blown up. The days of British Malaya were numbered.

On 8 February, Japanese troops crossed Johor Strait and established a bridgehead on Singapore Island, despite strong opposition from Australian troops. Casualties were heavy, and convoys of ambulances arrived at St. Patrick’s School carrying hundreds of wounded soldiers, mainly with gunshot and shrapnel wounds. The hospital was by now so overcrowded with wounded combatants that outbuildings and even tents were used as wards. The men lay tightly packed on floors and even on the lawns. Meanwhile, from outside the school came the constant noise of artillery fire.

EVACUATION

Reports of Japanese atrocities committed in Hong Kong and elsewhere brought pressure to bear on 8th Division headquarters to evacuate the AANS nurses. Maj. Gen. Gordon Bennett, officer in charge of the 8th Division in Malaya, had initially refused, arguing that such a move would affect morale, but on 9 February he relented. Despite pleas to stay with their patients, on 10 February six nurses were evacuated on the Wusueh, followed the next day by 60 or so on the Empire Star. Finally, on 12 February, the last 65 AANS nurses were evacuated on the small coastal steamer Vyner Brooke, among them Blanche.

As evening fell, the ship steamed slowly out of Keppel Harbour, leaving behind a devastated city. Over the next 36 hours it picked its way slowly through the maze of islands lining the passage between Singapore and Jakarta, and by early Saturday afternoon Captain Borton had reached Bangka Strait. To the right lay Sumatra; to the left, Bangka Island.

Out of the blue a Japanese spotter plane swooped over, followed by six dive-bombers. More than 20 bombs were dropped before three struck the ship. The Vyner Brooke began to list and within 30 minutes had sunk.

Blanche ended up clinging onto a raft, or rather two lashed together, with Veronica Clancy, Jean Ashton, Sylvia Muir and Gladys Hughes of the 2/13th AGH, Pearl Mittelheuser of the 2/10th AGH, and Mina Raymont and Shirley Gardam of the 2/4th CCS, together with a dozen or more civilian passengers. They swam and pushed the raft all night, and at one point they could see a bonfire on the shore between two lighthouses.

BANGKA ISLAND

Towards morning, Blanche, Gladys Hughes and Veronica Clancy began to swim for shore, which was now quite close. They were picked up, oddly, by two RAAF airmen in a launch, who then collected the remaining passengers and deposited them at the end of a long jetty at Muntok, the district centre. The RAAF men zoomed off again when Japanese soldiers appeared. During the night, the Japanese Army had launched an invasion of Sumatra, and Bangka Island was now under their control.

The Japanese soldiers took Blanche, the other nurses, and the civilian passengers to Muntok customs house and later to a cinema in town, where Blanche and her comrades were reunited with other surviving nurses. There were 31 of them. They did not know it yet, but 12 of their colleagues had been lost at sea when the Vyner Brooke was sunk.

Soon the nurses were taken with the other internees to a site on the edge of town, and here Vivian Bullwinkel of the 2/13th AGH joined them. She had survived an atrocious massacre of scores of service personnel, merchant sailors, civilians – and 21 of the nurses’ own colleagues. Of the 65 who had set out from Singapore on that fateful day, only 32 were still alive.

PRISONERS OF WAR

So began a long period of captivity for Blanche and the other surviving nurses, as well as the hundreds of interned women, children and men. They were held in six camps on Bangka Island and in southern Sumatra. They were subjected to systematic abuse and random acts of violence. They were slapped, yelled at and made to stand in the sun. They were threatened with starvation and, by the end, nearly did starve. They suffered debilitating diseases, particularly in the final two camps, Muntok on Bangka Island and Belalau on Sumatra, and had life-saving medicines withheld.

On 17 March 1943 Blanche and the other nurses were allowed to write home for the first and only time. Each was given a lettercard and instructed to write no more than 30 words, a stipulation that many of them ignored. Blanche’s mother received her lettercard in December and it was printed in the Brisbane Telegraph on 7 December, as follows:

The thrill of being able to write after 12 months’ silence and to let you know I am absolutely fit and well, in fact never felt better in health. Had trouble with my ear at first, always do with ocean water, but it was soon rectified. We are in a pretty little place, quiet and peaceful, away from any sort of turmoil. You will be disappointed to know your album is at the bottom of the sea. When allowed to send parcels please include a good strong tooth brush for we have lost everything, but nevertheless we are among friends who do their best to keep things and us well and contented. Sisters Short, Trotter and Blanche are here with me. Keep well and look forward to the happy day when you will be welcoming me home again.

Quite correctly, Mrs. Hempsted assumed that Blanche’s reference to ocean water affecting her ear indicated that the ship she was on must have been bombed prior to the fall of Singapore.

THE FINAL MONTHS

In November 1944, nearly three years into their ordeal, Blanche and the other internees were moved from Sumatra back to Muntok on Bangka Island. After some initial optimism, it proved to be the worst camp yet. Lice, scabies and bedbugs spread throughout the huts, and disease became rife. By January 1945 Bangka fever and beriberi were rife, and most of the nurses had malaria. Six were in hospital, four of them seriously ill – Mina Raymont from South Australia, Shirley Gardham from Tasmania, Rene Singleton from Victoria, and Blanche.

On 8 February Mina died of malaria. On 20 February Rene died of beriberi. On 19 March Blanche died too. After three years of toil – she was notorious for hard work – maltreatment, malnutrition and disease, her body had succumbed. She had been in the camp hospital since January and, knowing that the end was finally at hand, apologised for the trouble her illness had caused and for taking so long to die. She died half an hour later and was buried alongside her fallen comrades in a rough clearing in the jungle.

Five more nurses died before the survivors were finally rescued on 16 September. Shirley Gardam died on 4 April, Gladys Hughes on 31 May, Winnie May Davis on 19 July, Dorothy Freeman on 8 August, and Pearl Mittelheuser on 18 August – three days after Japan had formally surrendered.

Blanche was 36 when she died. On 5 November 1946 she was reburied at the Jakarta War Cemetery in Indonesia. Her name is memorialised on panel 96 in the Commemorative Area of the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

We will remember her.

SOURCES

- Arthurson, L., ‘The Story of the 13th Australian General Hospital, 8th Division AIF, Malaya,’ as presented by Peter Winstanley (2009).

- Fulford, S (2016), ‘Training, ethos, camaraderie and endurance of World War: Two Australian POW nurses,’ MPhil thesis, Curtain University.

- Goodman, R. (1985), Queensland Nurses Boer War to Vietnam, Boolarong Publications.

- Goossens, R. (‘SSMaritime’ website), ‘Wanganella.’

- Jeffrey, B. (1954), White Coolies, Angus & Robertson Publishers.

- Queensland Government, Queensland WWII Historic Places, ‘112th & 2/8th (2nd AIF) Army General Hospitals and 126th Army Special Hospital (ASH)’.

- Shaw, I. W. (2010), On Radji Beach, Pan Macmillan Australia.

- Simons, J. E. (1954), While History Passed, William Heinemann Ltd.

- Slade-St Catharine’s Past Students’ Association, Kinawah (Autumn 2016, p. 5), ‘St. Catharine’s Stanthorpe Student: Casualty of WWII’.

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS

- The Age (Melbourne, 31 Dec 1896, p. 5), ‘Queensland’.

- Bowen Independent (19 Apr 1940, p. 3), ‘Hospital Board’.

- The Brisbane Courier (20 Jul 1881, p. 1), ‘Classified Advertising’.

- The Brisbane Courier (2 Oct 1912, p. 3), ‘Water and Sewerage Board’.

- The Brisbane Courier (22 Apr 1925, p. 22), ‘Social Evening’.

- The Brisbane Courier (28 July 1926, p. 21), ‘Benefit Dance’.

- The Brisbane Courier (23 Oct 1926, p. 20), ‘Benefit Dance’.

- The Brisbane Courier (2 Jun 1927, p. 18), ‘Reunion Dance’.

- The Brisbane Courier (21 Mar 1932, p. 16), ‘Family Notices’.

- The Brisbane Courier (8 Apr 1932, p. 17), ‘Supper and Dance’.

- The Brisbane Courier (9 Apr 1932, p. 19), ‘Social’.

- The Brisbane Courier (15 Apr 1932, p.16), ‘Family Notices’.

- The Brisbane Courier (11 Nov 1932, p.18), ‘Benefit Evening’.

- The Brisbane Courier (2 Jan 1933, p. 15), ‘New Year Celebrations’.

- The Daily Mail (Brisbane, 12 Dec 1923, p. 3), ‘St. Margaret’s’.

- The Daily Mail (Brisbane, 11 Jun 1925, p. 6), ‘Boy Killed’.

- Queensland Figaro (Brisbane, 2 Aug 1906, p. 17), ‘Family Notices’.

- The Telegraph (Brisbane, 24 Mar 1906, p. 7), ‘Advertising’.

- The Telegraph (Brisbane, 16 May 1928, p. 11), ‘Harbour Lights Dance’.

- The Telegraph (Brisbane, 20 Apr 1929, p. 15), ‘Moonlight Concert’.

- The Telegraph (Brisbane, 7 Dec 1943, p. 3), ‘AIF Sister Safe in Palembang’.

- The Telegraph (Brisbane, 19 Mar 1947, p. 4) ‘Family Notices’.

- Townsville Daily Bulletin (17 Jan 1940, p. eight) ‘Collinsville Notes’.

- Townsville Daily Bulletin (13 Nov 1940, p. 6), ‘Collinsville Notes’.

- Warwick Daily News (8 Nov 1920, p. 6), ‘St. Martin’s War Memorial’.