QAIMNSR │ Staff Nurse │ First World War │ Egypt & HMHS Galeka

FAMILY BACKGROUND

Agnes Beryl Corfield, known as Beryl, was born in Brisbane on 27 April 1891 to Agnes Mary James (1860–1922) and George Edward Corfield (1859–1932).

Agnes James was the youngest of 10 children born to Elizabeth Gardner and William James of Prahran, Melbourne, who were married in England and arrived in Melbourne in 1852. When Agnes was just eight or nine years old her mother died, and it appears that she may have travelled to Brisbane with older sisters in 1884.

George Corfield was born in Amherst in Victoria’s goldfields. He was the eldest of eight children born to Margaret Duffy from Ireland and George C. Corfield from England. After his father earned money on the goldfields (selling shoes, according to a family story), George junior was sent to an elite school in Melbourne. Around 1884 he travelled to Brisbane, where he resided on Shafston Road, Kangaroo Point and worked as a clerk. He met Agnes and they were married on 8 October 1886 at Agnes’s sister’s house by the well-known Baptist minister the Rev. William Poole. Afterwards they resided at ‘Malvern’ on Longlands Street in East Brisbane.

Agnes and George began their family in 1887 with the birth of George Herbert. He was followed by Charles William in 1889, Beryl in 1891 and Constance Bessie (Connie) in 1893. By 1894 the family was living on Rokeby Terrace in Taringa.

SCHOOL

In 1896 the Corfields moved from Brisbane to Maryborough, 220 kilometres to the north. They lived on Fort Street and George worked as a bookkeeper. On 17 August the boys, George and Charles, began attending the Central Boys’ State School, while Beryl started at the Central Infants’ State School, presumably at around the same time. She attended for the remainder of 1896 and then 1897.

Having aged out of the infants’ school, on 4 July 1898 Beryl began attending the Central Girls’ State School, apparently co-located on Kent Street with the infants’ school and the boys’ school. By now the Corfields had moved to King Street and George Corfield was bookkeeping for Hyne & Son, timber merchants. A month after Beryl began at the girls’ school, Winsome May, known as Winnie, was born, Agnes’s and George’s fifth and final child.

Perplexingly, at the time of Winnie’s birth, Beryl was temporarily attending West End Girls’ State School in Brisbane, having been added to the admissions register on 26 July – only three weeks after starting primary school in Maryborough. Her attendance at the school concluded in September, at which point she presumably returned to Maryborough. Just why Beryl should have been enrolled in a school in Brisbane at this time is a mystery.

Beryl returned to Maryborough and resumed her schooling at the Central Girls’ State School. She was clearly an engaged pupil, for in December 1899, at the school’s end-of-year prize-giving ceremony, she was awarded the Class IIA prize for conduct. The following year, in Class IIIB, she was again awarded the conduct prize.

LIZZIE RYLAND

At school Beryl became best friends with a girl by the name of Elizabeth Jane Blackburn Ryland. Lizzie, as she was known, was three months older than Beryl and had lost her mother when she was just a month old. Her father, a postal worker and champion draughts player, had remarried when she was five. Her father’s mother, incidentally, was the first matron of the Lady Musgrave Hospital in Maryborough – where Beryl would one day nurse.

Beryl and Lizzie completed their primary schooling at the end of 1904, and Lizzie was granted a scholarship to Maryborough Girls’ Grammar School. However, we do not know which secondary school Beryl went to. She may in fact have travelled north with her family.

Sometime in 1905 George Corfield was employed as a bookkeeper by Messrs. J. Vidulich & Co., sawmill operators in Mackay, a coastal town 700 kilometres north of Maryborough. In January 1906 he was appointed permanent secretary of the Cattle Creek Central Mill Company, a sugar refinery based in Finch Hatton, 60 kilometres west of Mackay. In May he was appointed Public Officer for the company. It is not clear whether his family accompanied him, and by the end of 1906, or soon after, George appears to have returned to Maryborough.

SUNDAY SCHOOL

Beryl and Lizzie Ryland were both pupils at the Maryborough Baptist Church Sunday School. In June 1907 the two of them sat the Queensland Sunday School Union scripture examination, which was held annually at mid-year. Beryl came equal ninth in the upper intermediate division with 75 marks, while Lizzie gained a score of 68 marks. In the same examination in 1908 Lizzie came second and Beryl eighth. In August that year it would appear that Lizzie departed for Brisbane with her father and stepmother. She later trained to be a Sunday School teacher and then worked for the post office. However, her role in Beryl’s story is far from finished.

Meanwhile, in 1908 Beryl was studying stage-one shorthand at the Maryborough Technical College. In the examination held at the end of that year she achieved 80.5 per cent, giving her an honours pass. She was awarded her certificate in July 1909.

In June 1910 Beryl once again undertook the Queensland Sunday School Union scripture examination and came third in the senior division, with 88 marks. However, in May 1911 she ended her association with the Baptist Church Sunday School. She was going to Brisbane to train as a nurse.

NURSING AND WAR

Beryl had been accepted into a three-year course as a pupil nurse at Brisbane General Hospital. In October 1913 she passed her final-year examination and on 19 August 1914 successfully sat her Nurses’ Registration Board examination, qualifying her for registration. After completing her training Beryl was appointed to a position at the Lady Musgrave Hospital in Maryborough.

By now Australia had gone to war, and over the coming months hundreds of Australian nurses would join the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS). Others would serve by joining private organisations such as Mrs. Stobart’s Women’s Imperial Service League and Lady Dudley’s Australian Voluntary Hospital, or institutional organisations such as the Red Cross Society.

QUEEN ALEXANDRA’S IMPERIAL MILITARY NURSING SERVICE RESERVE

Other nurses joined the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service Reserve (QAIMNSR), the British equivalent of the AANS. Some travelled to England to join, covering their own expenses. Others were sponsored by the Commonwealth Government following a request by the British War Office. Beryl was one of these. After applying in the first months of 1915 she was accepted into a contingent of 36 nurses due to be sent to England in May.

Upon learning of her acceptance Beryl resigned her position at the Lady Musgrave Hospital. On 30 April she attended a farewell supper organised by Matron Maxwell and the nursing staff of the hospital and soon after departed Maryborough by the mail train for Brisbane. On 13 May Beryl entrained for Sydney, and among those to see her off at the station was Lizzie Ryland.

RMS MOOLTAN

After a journey of some 28 hours, Beryl arrived in Sydney on 14 May. In due course, either that day or the next, she boarded the Royal Mail Ship Mooltan and was officially appointed to the QAIMNSR. On board the ship Beryl met her fellow QAIMNSR appointees – or at least those who were embarking in Sydney. Among them were Queenslanders Blanche Geary and Mary McGrath, Ruth Bottle from Victoria, Marjorie Pearson from New South Wales, and Edith Twelvetrees from Tasmania.

Also on board the Mooltan were around 220 staff of No. 3 Australian General Hospital (AGH), including 38 AANS nurses, among them Principal Matron Grace Wilson. No. 3 AGH was bound for England, from where it would transfer, so the staff thought, to France. In fact, the unit was destined to wind up at Mudros on the Greek island of Lemnos, which lay around 100 kilometres to the west of the Gallipoli Peninsula. Here, the nurses, medical officers, orderlies and other staff would work under difficult and rudimentary circumstances to save the lives of the many thousands of casualties brought to them from the beaches of Gallipoli.

In addition, the ship was carrying reinforcements for No. 1 AGH. No. 1 AGH had arrived in Egypt on the Kyarra in January and was based at Heliopolis, a new suburb 10 kilometres northeast of central Cairo. Its sister hospital, No. 2 AGH, had travelled to Egypt on the same ship and was based at Mena House, near the Pyramids of Giza, on the opposite side of Cairo from Heliopolis. Now a further 38 AANS nurses and around 185 other staff of No. 1 AGH were being sent to Heliopolis, most of whom would board in Melbourne.

On 15 May the Mooltan sailed out of Sydney Harbour and two days later arrived in Melbourne. The QAIMNSR nurses were joined by fellow appointee Kathleen Gawler, who would serve with Beryl and Edith Twelvetrees at their hospital in Alexandria. Also boarding in Melbourne were 30 AANS nurses and 10 other staff of the 3rd AGH, as well as most of the No. 1 AGH reinforcements.

After leaving Melbourne, the Mooltan called into Port Adelaide and Fremantle, where more staff of each of the two AGHs boarded.

The Mooltan sailed from Fremantle on 24 May and arrived in Colombo, Ceylon several days later. Here, the nurses of No. 3 AGH were allowed shore leave, so presumably the QAIMNSR nurses were too. However, fighting between Buddhist and Muslim communities curtailed the nurses’ freedom. The Mooltan left Colombo on 3 June, stopped at Bombay and Aden, and arrived at Port Tewfik, the port of Suez, on the morning of 15 June. Here the No. 1 AGH reinforcements left the ship.

So did the QAIMNSR nurses. Beryl and her colleagues were met on board and then escorted to the railway station at the port, wondering where on earth they were going. They soon learned that their destination was Alexandria, on Egypt’s Mediterranean coast, and at 1.00 pm boarded a train and set off for the ancient city. The Mooltan continued on its way. It arrived at Plymouth, England on 27 June and on 1 July No. 3 AGH staff were deployed to Lemnos.

ALEXANDRIA

In a letter written on 6 July to Lizzie Ryland, Beryl described a hellish train trip from Suez to Alexandria. While travelling northwest through the desert, the train passed through a sandstorm. Naturally the windows and shutters had to be shut, and the heat inside the carriages reached 120 Fahrenheit – the worst experience of Beryl’s life, she reckoned.

Halfway through the journey several of the Australian QAIMNSR nurses disembarked, possibly at the junction town of Banha, to take another train to Cairo. Meanwhile, Beryl, Kathleen Gawler, Edith Twelvetrees, Blanche Geary, Mary McGrath and the rest continued on to Alexandria. As dusk came on, the temperature inside the carriages began to drop, and by the time the train pulled into the station at Alexandria late at night, it had reached a comfortable level.

Outside the station, the nurses were met by vehicles. Some of the nurses, including Blanche and Mary, had been attached to No. 17 General Hospital (GH), a British military hospital, and were taken to Victoria College in the Ramleh district of Alexandria, where the hospital was based. Others, including Beryl, Kathleen and Edith, had been attached to No. 15 GH. However, instead of being taken to their hospital, they were taken to a hotel. The nurses’ quarters at No. 15 GH were being used to accommodate casualties of the fighting on the Gallipoli Peninsula, so for the time being they were to be billetted externally. Beryl was impressed by her room and the meals at the hotel but considered the board somewhat expensive.

For the next few weeks Beryl and her colleagues shuttled between the hotel and No. 15 GH in motor ambulances. No. 15 GH had arrived in Alexandria on 15 March. By 1 April it had taken possession of the Abassieh Secondary School, on Rue Muharram Bey, close to the main railway station. Within a short time the unit had prepared 1,000 beds for the reception of sick and wounded from Gallipoli – a number that eventually rose to 1,700.

Beryl found Alexandria fascinating and most enjoyable – despite the fact, as she told Lizzie, that the “markets & nature quarters are unmentionable for dirt and smell.” She noted that the city was full of British soldiers and she appreciated the shopping, in particular the lovely clothes at very cheap prices. At one point, when sightseeing with one of the other nurses, she ran into an acquaintance from Maryborough, a certain Colonel Lee, who proceeded to entertain the two women.

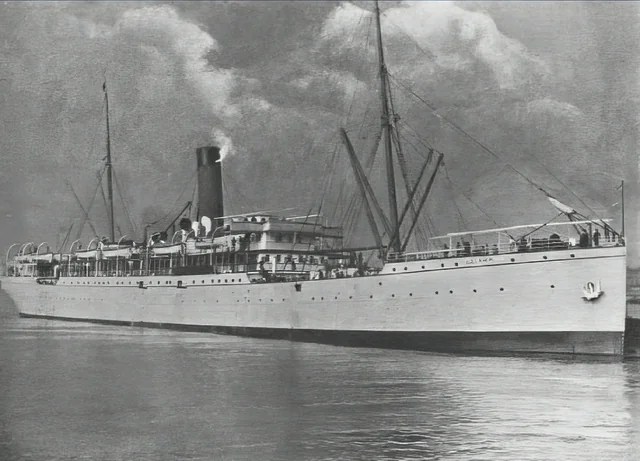

HMHS GALEKA

In early July, after three weeks in Alexandria, Beryl and one other Australian QAIMNSR nurse from No. 15 GH were detailed for duty on His Majesty’s Hospital Ship Galeka. In early May the Galeka had transported Anzacs from Mudros Harbour on Lemnos to the Gallipoli Peninsula. It had then made two runs as an unofficial medical transport ship (sometimes known as ‘Black Ships’) from Mudros to Alexandria with hundreds of casualties from the Gallipoli campaign, who were transported under appalling conditions. In June the ship was refitted and on 22 June recommissioned as a hospital ship. Now, in early July, HMHS Galeka was waiting to sail to the Gallipoli Peninsula to embark wounded soldiers for transportation to British military hospitals on Malta. The ship’s medical staff comprised eight nurses – two of whom were Australian, Beryl and her friend – four officers, and six medical officers.

The Galeka departed Alexandria on 10 August and sailed to Mudros Harbour, arriving two days later at midday. At 6.00 pm the staff received orders to proceed to the peninsula – where, just days earlier, the Allies had launched a last-ditch offensive. It had already resulted in thousands of casualties and was doomed to fail.

At 7.00 pm the Galeka sailed for Kephalos Bay on Imbros Island, which lay only 20 kilometres to the west of the peninsula. When Beryl wrote to Lizzie on 29 August she described the excitement of that night – and the horror and misery that followed:

At 9 pm the excitement began. All lights were lowered & we travelled at the great rate of 3 knots an hour – in fact we barely moved at all, we were going so slowly as travelling is very dangerous … At 9 pm flashes began to appear ahead [which] were the shells bursting over the peninsula. We all stayed up until midnight watching the flashes of the guns and the different warships going past. We were all made to try on our life belts & leave them, with a box of matches by the side of our beds. We crawled away until dawn then at last [Cape Helles] appeared in the distance. At 7 am we entered Imbros Harbour … We spent a few hours at Imbros then received orders to proceed over to the peninsula.

HELLES BAY, GALLIPOLI PENINSULA

The Galeka passed alongside Gaba Tepe (or Kabatepe), a strategically important promontory just south of Anzac Cove, and then drew into Cape Helles. The cape lay at the southern tip of the peninsula and was where British and French troops had landed on 25 April. The ship stayed here for 10 days, each day embarking the wounded from the renewed fighting. From on board Beryl could see shells bursting in the trenches and on the hills.

Beryl’s letter continued:

All the smoke & sand would fly everywhere, but the noise – sometimes for 24 hrs the constant boomb boomb would never stop I used to feel that I would go mad if they didn’t stop – what our boys have gone through on that peninsula God only knows. We were not allowed to leave the boat, as shells were bursting just near us on the beach. Some of the medical officers landed at their own risks for a few hrs but we were not allowed to.

The worst part of Beryl’s experience was the noise and vibration of the guns of the Allied monitors (small warships). “I shall never forget the first Sunday night [15 August],” she told Lizzie.

Our monitors were trying to put some guns out of action on the Asiatic shore that were doing a lot of damage. You know how in Queensland in a bad storm there is a flash of lightning then at the same time a crackling noise of thunder, which dies away with a sort of vibration well that is as near as I can describe it, only the vibration is terrific on the water you feel as if it were in your own head & for some minutes afterwards you are completely deaf. This kept up for hours with intervals of five minutes. You can imagine the condition our nerves got in.

By the morning of 16 August six of the Turkish guns had been silenced and a powerful Turkish searchlight destroyed. But the casualties kept coming:

Of the wounded that followed all the firing we heard each night I will say nothing, but you will imagine something of their cut up condition when I tell you we had 50 deaths on the two days run to Malta afterwards. Oh Lizzie you have not the faintest idea of what war is like you don’t know what we have been through – to sit & hear the firing & see the dust & smoke & to know that in a few hours the wounded will be brought on from that very shell. Of the ones that are killed & that are so bad that they don’t bring them to us we hear nothing If I were a soldier I should pray day & night to be killed right out , but to see men come into your ward with legs off arms off – mouth and tongue or lower jaw blown off you would wonder what it is all for & with whom the great reckoning will be.

TO MALTA AND ENGLAND

Around 22 August the Galeka set sail for Malta with its “mangled heap of humanity,” as Beryl so viscerally and tragically described the ship’s cargo of hundreds of wounded and dying men in her 29 August letter. During the two-day passage the ship encountered rough weather, and although Beryl was generally “a good sailor,” as she put it, on the second day she vomited. With 80 dreadful cases to look after, a strong headwind, a rough sea, terrific heat, and working in the hold of a boat 15 hours a day for 11 days, this was hardly surprising.

Eventually the day described by Beryl as “hell” ended, and at dawn the next morning, possibly 24 August, the Galeka arrived at Malta. The ship entered one of the two main harbours at Valletta, and the patients were disembarked and sent to various hospitals. Then came the order to transport convalescent patients to England.

The Galeka set out from Malta bound for Southampton with 350 or more patients aboard. The worst cases travelled in cots while the others were on mattresses spread out six inches apart on the floor. By 29 August the Galeka was nearing Gibraltar and Beryl anticipated reaching Southampton by 4 September.

LONDON AND BACK TO ALEXANDRIA

In due course the Galeka arrived in Southampton, and the patients were disembarked. Beryl then made her way to London and enjoyed some much-needed time off. She attended mass at St. Paul’s Cathedral and at the Temple Church in the Law Courts precinct. She visited Kensington Gardens, Albert Hall, Hyde Park, and sites associated with Charles Dickens. She attended theatre performances and concerts. During her stay, London was attacked twice in 24 hours by German Zeppelins. The second raid, which took place on the night of 8–9 September, destroyed a hotel close to the one Beryl was staying in on Southampton Row in Bloomsbury.

By 21 September Beryl had returned to duty on the Galeka and had arrived once again in Malta en route to Alexandria. Assuming the ship departed the same day or the following, it must have reached Alexandria by 24 September – a turnaround period of six weeks.

When Beryl wrote to Lizzie again on 10 December she noted that she was back at No. 15 GH – suggesting that she had had further hospital ship duty. Her letter is particularly sentimental. Beryl missed her dear friend very much and wished that Lizzie could be beside her serving as a nurse. She was on night duty, and every patient in her ward was suffering from terrible frostbite. “If you could only see their poor feet,” Beryl wrote. “Lots of them will have to [lose] them altogether – you cannot imagine anything so dreadful – I would rather nurse wounded fifty times than this.”

However, following the decision to evacuate the Gallipoli Peninsula and the subsequent drawing down of troop numbers, there were fewer and fewer wounded men being admitted to No. 15 GH. Of the hospital’s 1,600 patients, only 100 were battle casualties. The others were suffering from such conditions as malaria, dysentery, enteric fever (typhoid) – and, overwhelmingly, frostbite.

Beryl told Lizzie that she had narrowly avoided being detailed for duty in Salonika, northern Greece, where a front had opened in October. Conditions in Salonika were extremely difficult for patients and staff alike at the numerous Allied hospitals that had already been established. Infrastructure and facilities were rudimentary, and the winter was proving particularly harsh.

TO CAIRO AND BACK

Beryl’s next letter to Lizzie, written on 6 January 1916, struck a lighter tone. Following the death in her ward of a patient with rabies, she and several other staff of No. 15 GH had been sent to Cairo and were staying at the Semiramis Hotel. They required preventative treatment consisting of a single needle daily, but otherwise were free to explore the city of the pyramids. It was winter of course and cold and rainy – a “real English winter,” wrote Beryl – but this did not stop them. Naturally they visited the Pyramids of Giza, which Beryl could see from her room in the luxury hotel, but they also visited the older pyramid of Saqqara, located further south. They attended an ‘At home’ function given by the officers at Mena Camp, a nearby Australian army camp, and then attended a concert. On another occasion they visited the Cairo Museum. They were accompanied by the very Egyptologist who had discovered the tomb of Ramses II – the “Pharoah who talked with Moses,” as Beryl put it. She told Lizzie how pleased she was to have been the only one of her party of four officers and three nurses to have known the Biblical story of Moses and Ramses II.

After spending 19 days in Cairo, Beryl returned to Alexandria and on 27 January wrote to Lizzie again. She had had a most memorable time in the Egyptian capital and was now back at work in a ward opened up for a convoy of surgical cases expected any day. She had only 16 patients at that moment but told her friend that “when the convoy arrives then things will hum with a vengeance.”

Nonetheless, patient counts in general were falling at hospitals in Alexandria. The Gallipoli campaign was over, the final troops had been evacuated from the peninsula, and military hospitals were beginning to reduce their bed numbers. No. 15 GH itself was due to close 500 of its 1,700 beds that week. Further, it was rumoured that the hospital might be relocated. In the event, No. 15 GH did not close until April 1918, at which time the unit’s staff were transferred to Salonika to form No. 64 GH.

All of this happened in a future that Beryl was not part of. Soon after writing to Lizzie on 27 January she became ill. She may even have been ill while writing, but if so, gave no indication.

On 2 February Beryl died of pneumonia while a patient at No. 15 GH. She was buried in the Chatby Military Cemetery, known today as the Alexandria (Chatby) Military and War Memorial Cemetery.

We will remember her.

SOURCES

- Ancestry.

- Australian Nurses in World War I (website).

- Australian Nurses at War (website).

- Australian War Memorial, Letters from Sister Corfield during 1915 to her best friend Lizzie Ryland (AWM2017.7.322).

- Great War Forum, ‘No.15 General Hospital, Alexandria,’ ‘BJanman,’ posted 16 Feb 2010.

- Great War Forum, ‘No.15 General Hospital, Alexandria,’ ‘grantmal,’ posted 15 Feb 2010.

- The National Archives (UK), Blanche Geary WO-399-3043.

- The National Archives (UK), Kathleen Gawler WO-399-3039.

- The National Archives (UK), Marjorie Pearson WO-399-6567.

- The National Archives (UK), Mary McGrath WO-399-5205.

- The National Archives (UK), Ruth Bottle WO-399-778.

- Queensland State Archives, Admission Register – Maryborough Central State Boys’ School, (1884–1907).

- Queensland State Archives, Admission Register – Maryborough Central State Girls’ School (1875–1905).

- Queensland State Archives, Admission Register – West End Girls’ School (1880–1912).

- State Library of New South Wales (Mitchell Library), ‘Sister Anne Donnell circular letters, with diary 25 May 1915–31 Jan 1919’ (ML MSS 1022).

- Virtual War Memorial Australia, ‘Agnes Beryl Corfield,’ contributed by Heather Ford.

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS AND JOURNALS

- The Brisbane Courier (Qld., 23 Oct 1886, p. 4), ‘Family Notices.’

- The Brisbane Courier (Qld., 1 Jul 1907, p. 2), ‘Queensland Sunday School Union.’

- British Journal of Nursing (Vol. 55, p. 69, 24 Jul 1915), ‘Nursing and the War.’

- Bundaberg Mail and Burnett Advertiser (Qld., 10 Feb 1916, p. 3), ‘Death of Nurse Corfield.’

- Daily Mercury (Mackay, Qld., 20 Jan 1906, p. 2), ‘Mill Secretaryship.’

- Daily Mercury (Mackay, Qld., 12 May 1906, p. 2), ‘Cattle Creek Company.’

- Daily Standard (Brisbane, 17 Oct 1914, p. 4), ‘Nurses’ Exams.’

- Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld., 9 Dec 1896, p. 3), ‘The Central Infants’ School.’

- Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld., 9 Dec 1897, p. 3), ‘Central Infants’ State School.’

- Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld., 23 Nov 1898, p. 3), ‘District Court.’

- Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld., Dec 1899, p. 3), ‘Girls’ School.’

- Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld., 15 Dec 1900, p. 4), ‘Girls’ School.’

- Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld., 26 Jan 1905, p. 2), ‘General News.’

- Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld., 14 Aug 1908, p. 2), ‘General News.’

- Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld., 28 Jan 1909, p. 3), ‘The Technical College.’

- Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld., 8 Jul 1909, p. 3), ‘Technical College.’

- Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld., 25 Jul 1910, p. 2), ‘General News.’

- Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld., 8 May 1915, p. 9), ‘Social.’

- Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld., 19 Aug 1918, p. 3), ‘Death of Mr. Jonathan J. Ryland.’

- Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld., 26 Apr 1920, p. 4), ‘Baptist Church Service.’

- Maryborough Chronicle, Wide Bay and Burnett Advertiser (Qld., 27 Jun 1932, p. 4), ‘General News.’

- The Telegraph (Brisbane, 26 Mar 1914, p. 5), ‘Advertising.’

- Townsville Daily Bulletin (Qld., 1 Jul 1915, p. 11), ‘Gossip.’

- The Week (Brisbane, 28 Sept 1923, p. 31), ‘Sunday School Work.’