AANS │ Major │ Second World War │ Sea Ambulance Transport Unit, 1st Netherlands Military Hospital Ship Oranje & 2/3rd Australian Hospital Ship Centaur

EARLY LIFE

Sarah Anne Jewell, known as Anne, was born in Subiaco, Perth, on 11 May 1901. Her mother, Charlotte Lillian (Lil) Freeman (1868–1923), was from Ballarat in Victoria, and her father, Edward (Ted) Jewell (1867–1949), was from Bacchus Marsh, also in Victoria. Ted was self-employed as a painter and handyman and in the 1890s had been a prominent road and track racing cyclist. He also played the horn in brass bands. He joined his first band in Ballarat in 1886 and belonged to military and other bands for the rest of his life.

Lil and Ted were married in Ballarat on 15 August 1885. The following year, their first child, Lily, was born. Two more children were born in Ballarat, Edward in 1888 and Harold (sometimes known as ‘Poss’) in 1891, before the family moved to Maryborough, 50 kilometres to the north. Here two more children were born, Maggie in 1894 and Alex in 1896.

Baby Alex died only four months after his birth. To compound the tragedy, in January 1896 Ted Jewell had become insolvent. The family decided to relocate to Western Australia and by 1898 were living on William Street in Subiaco, at the time a new suburb a few kilometres to the west of central Perth.

In Subiaco three more children were born, Myrtle in 1898, Anne in 1901 and finally Alfred (known variously as Reggie and Dick) in 1903. (Sadly, two further children, a baby girl and a baby boy, were stillborn in 1905 and 1906 respectively.)

GROWING UP

Anne and her siblings attended Subiaco State School, which was located between Hammersley and Bagot Road, around a kilometre away from their house on William Street. The school comprised an infants’ school and a senior school. Anne also went to Rosalie Sunday School.

At the age of nine, Anne sent a delightful letter to ‘Auntie Nell,’ the editor of the children’s section of The Daily News. It was printed on 23 July 1910 as follows:

William-street, Subiaco.

Dear Auntie Nell, – I am just sending you a few lines to ask you if I may become one of your nieces. I would like to join the Sunshine League. I am sending you twopence to help the Children’s Hospital. l am aged nine. I have just turned nine on the 11th of May. I know some children who have joined your league, and have seen many nice letters in ‘The Daily News.’ I am going to try and send you something if I can every time I send you a letter. I must now close, hoping I can join the league. – I remain, yours faithfully,

ANNIE JEWELL.

In March 1913, at the Nedlands Baths, Anne and her sister Myrtle gained their proficiency certificates in lifesaving from the Royal Life Saving Society. They were under the instruction of Mrs. de Mouncey, who trained many children in lifesaving skills.

During the Great War, Anne, like all children across the country, took part in school and community activities to help Australian soldiers and to help displaced French and Belgian civilians. In June 1916, for instance, she appeared as one of a ‘Scotch Set’ at a children’s fancy dress ball organised by the Caledonian Society to raise money for the Red Cross. It was held at the Perth Town Hall.

On 16 August 1923, Anne’s mother died suddenly at the family home in Subiaco. She was buried the next day in the Methodist portion of the Karrakatta Cemetery. Following the death of her mother, Anne entered the Education Department, despite her wish to take up nursing, to help to keep the home going.

NURSING

Anne had always wanted to be a nurse. When her father was interviewed by the Perth Daily News on 19 May 1943, he recalled that when Annie was a child, she often disappeared from the house. “But her mother knew exactly where to find her – watching over the cot of the newest baby in the neighbourhood.” Ted Jewell told the newspaper that when Anne did eventually begin her nurses’ training at Perth Hospital (around 1924), she was over the moon. When she came second in the state in her final exam in 1926, “there was no happier girl in Perth.” And when “she became a nurse she realised her greatest ambition.”

Having completed her training, Anne spent a period of time in private nursing in Perth and then moved to Wickepin in Western Australia’s Wheatbelt region, where she was sister at Wickepin District Memorial Hospital. She was reportedly very popular with the patients. She left in mid-July 1927 and returned to Perth.

Four months before Anne’s return to Perth, her sister Lily died at her home in Leederville. Tragedy struck again in August 1928, when Annie’s sister Maggie died in Subiaco. In the space of only five years, Ted Jewell had lost his wife and two daughters. He was able to find joy, however, in his marriage in 1927 to Emily Wilson Cole, whose son, Jack Cole, thus became Anne’s stepbrother.

Around 1929 Anne moved to Victoria, where she took up a position as sister in charge of welfare work and treatment of accident cases at H. V. McKay Massey Harris Pty. Ltd. (also known as the Sunshine Harvester Works), in Melbourne’s industrial western suburbs. She stayed there until mid-July 1936. At her farewell, Anne was presented with a handbag containing £83 and lauded by Mr D. B. Ferguson, chairman of directors. He said that during her time with the company, she had displayed such qualities of kindliness, and such a sympathetic and patient disposition, that the burden of pain that her patients had borne was lessened considerably.

For the next five years, Anne worked for a Collins Street specialist, Dr (Reginald) Frank May, whom she had met in her Perth training days, in the physiotherapy department of the Epworth Hospital. At this time, she was residing at 28 George Street in East Melbourne. She shared the flat for at least some of the time with her close friend Miss Aura Forster, of Armidale, New South Wales, who also worked at Dr. May’s clinic.

ENLISTMENT

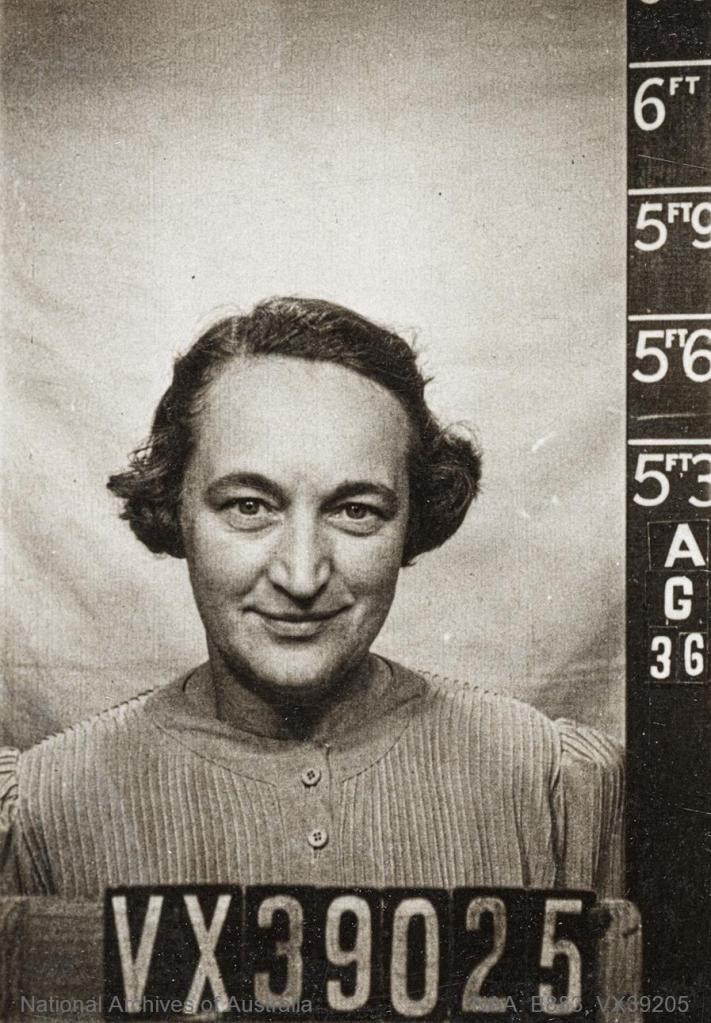

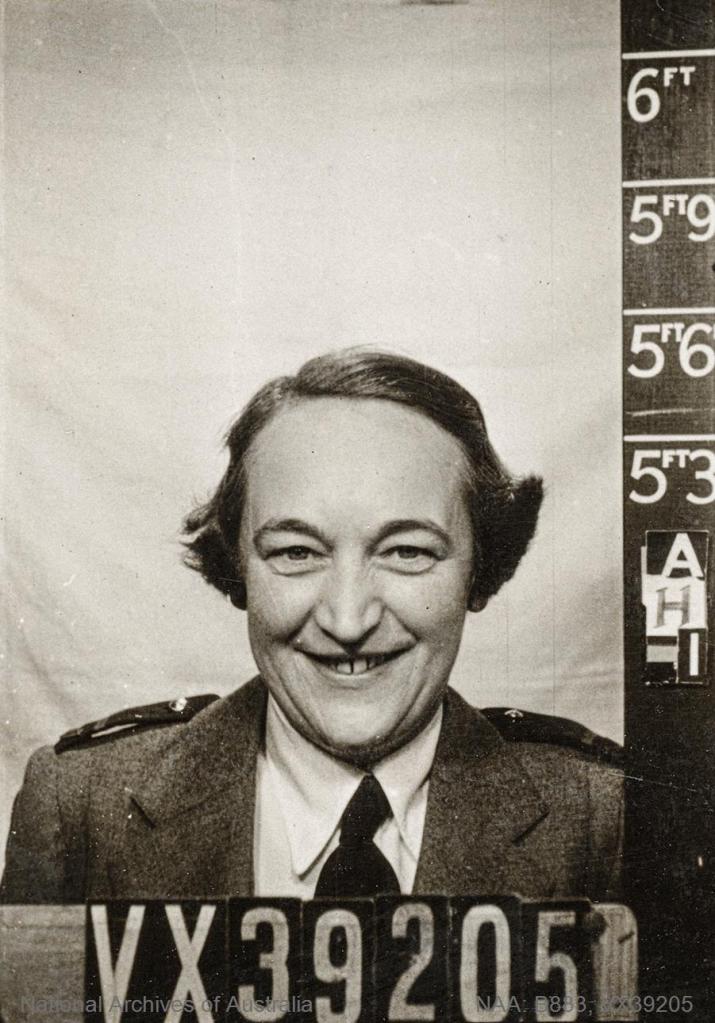

Anne was still working for Dr. May when she applied to join the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS). War had broken out in Europe, and she wanted to play her part. She was accepted into the AANS on 26 June 1940 and appointed to the rank of staff nurse.

After attesting for home service with the Citizen Military Forces on 7 November, Anne was seconded to the Second Australian Imperial Force at the rank of sister on 21 December. On 30 December she was detached to the Sea Ambulance Transport Unit (SATU), responsible for transporting ill and wounded Australian and New Zealand troops back home from the Middle East.

However, on that same day Anne began a period of leave without pay. She returned on 29 January 1941 and immediately went on pre-embarkation leave. When she returned on 3 February she was posted to the 107th Australian General Hospital at Puckapunyal army camp in central Victoria. Finally, on 8 April Anne embarked for the Middle East with the SATU.

Anne spent the remainder of 1941 shuttling between the Middle East and Australia with the SATU. Then, after being promoted to the rank of matron on 16 January 1942, eight days later she was appointed to the hospital ship Oranje.

THE ORANJE

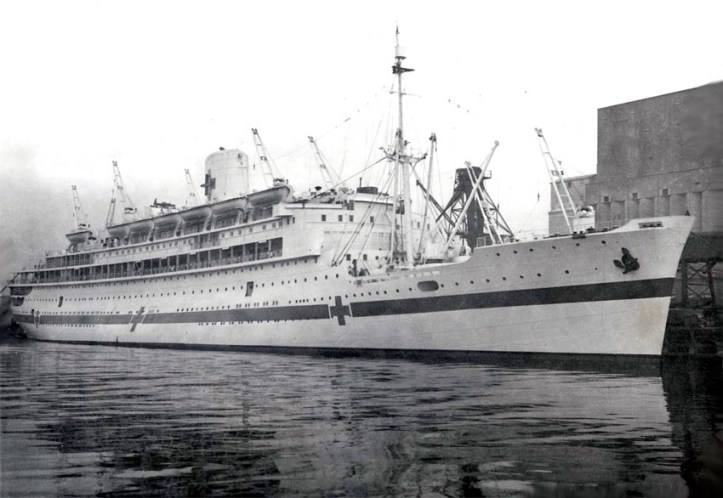

The Oranje was a grand Dutch passenger liner that had become stranded in the Netherlands East Indies (NEI) following the outbreak of war in Europe. In February 1941 the NEI government offered the vessel to the Australian and New Zealand governments for the repatriation of sick and wounded Anzacs. On 1 April the Oranje arrived in Sydney from Surabaya and was moored at Cockatoo Island dockyard for conversion.

By the end of June, the Oranje had been recommissioned as the 1st Netherlands Military Hospital Ship Oranje. With a predominantly Dutch medical staff, it made two voyages to the Middle East to repatriate Australian and New Zealand soldiers.

Following the Netherlands’ declaration of war against Japan, however, many of the Oranje’s Dutch medical personnel were ordered to return to the NEI, and Australians and New Zealanders were recruited to take their places. Among those attached were AANS nurses Margaret Adams, Cynthia Haultain, Eva King, Eileen Rutherford, Jenny Walker – and Anne. Another AANS nurse, Sister Mary McFarlane, had been on the ship as a liaison officer from the beginning and remained on board. These seven nurses would stay together for the next 15 months, later serving together on the AHS Centaur.

On 27 January 1942 the Oranje embarked from Sydney on its third voyage under dramatically different conditions. Japanese forces had now all but taken the Malay Peninsula, were on the cusp of invading Singapore, and had their sights set on the NEI. In view of this the ship sailed directly to Aden from Fremantle, thereby avoiding southeast Asia. From Aden the Oranje continued as usual to Port Tewfik, where more than 600 patients were embarked. The Oranje then returned to Australia and reached Sydney on 9 March.

As the situation in the NEI worsened, more Dutch staff were obliged to leave the Oranje and were replaced by Australians and New Zealanders, including Staff Nurse Nell Savage.

The Oranje departed on its fourth voyage on 24 March and completed several more voyages in 1942 and into 1943. However, its return to Sydney on 1 March 1943 marked the end of Australian involvement with the ship. Australian medical staff were urgently needed in Australia and New Guinea due to the growing Japanese threat and were withdrawn, to be replaced by New Zealanders, and the Oranje was relocated to the Middle East and Mediterranean. However, within a fortnight, most of the Australian staff, including Anne and seven other Oranje nurses, were reassigned to another hospital ship, the Centaur.

THE CENTAUR

MV Centaur was built in Scotland in 1924 and arrived in Australia that same year to ply a route between Fremantle and Singapore. In 1940 the ship was placed under the control of the British Admiralty but continued its normal operations. At the start of 1943, following a request for a ship capable of serving in shallow southeast Asian waters as a hospital ship, the Centaur was loaned to the Australian government. It was converted in Melbourne and commissioned in March as 2/3rd Australian Hospital Ship Centaur. On 12 March the Centaur departed for Sydney on the first part of a trial voyage, during which several shortcomings were identified. The ship remained in Sydney while they were rectified.

On 17 March Anne and her Oranje colleagues Sisters Margaret Adams, Cynthia Haultain, Eva King, Mary McFarlane, Eileen Rutherford, Nell Savage and Jenny Walker boarded the Centaur in Sydney. They were joined by Sisters Myrle Moston, Alice O’Donnell, Edna Shaw and Joyce Wyllie. Anne was matron and Mary McFarlane her second in charge.

The Centaur resumed its trial run on the morning of 21 March, when it departed for Brisbane. It arrived on 23 March and sailed again on 1 April for Townsville. Here Australian casualties repatriated from New Guinea were embarked, transported to Brisbane, and on 7 April disembarked at Newstead Wharf.

For the final leg of the trial, the Centaur sailed from Brisbane to Port Moresby with medical personnel and returned with Australian and American wounded, along with several wounded Japanese prisoners of war. When it reached Brisbane on 18 April, the Centaur’s effectiveness as a hospital ship had been demonstrated.

THE FINAL VOYAGE

At 10.45 am on 12 May, a little over three weeks after arriving back in Brisbane, the Centaur departed Sydney bound for New Guinea. It was to be its final voyage. The ship was tasked with transporting 193 members of the 2/12th Field Ambulance to Port Moresby and then embarking Australian casualties for repatriation. Among the medical staff on board that day were eight doctors, a pharmacist and Annie and her 11 nurses.

On the evening of the 13 May, while the Centaur was off the northern New South Wales coast, a party was held for Anne, whose birthday it had been two days earlier. Arthur Waddington was the nurses’ steward and later described the party in a story published in The Australian Women’s Weekly. “Just a few hours before the torpedo hit I had seen those nurses so happy,” Arthur recalled.

The matron in charge of the nurses, Matron Ann Jewell, who went down with the ship, was celebrating her birthday with a party. The nurses had decorated the dining-table with flowers and everything looked very jolly. The party started at dinnertime and there was a lovely birthday cake for her. The nurses bought it in Sydney, and the ship’s cook iced it. It was white icing and had ‘Happy Birthday from the Centaur’ written in pink across it. I noticed that it wasn’t finished at dinner, and they took it to the main saloon to finish it off during the evening. Matron cut a slice for them all. A special menu was served that night, too. I meant to ask her the next day, just for a joke, just how old she really was. I was going to remark that there weren’t any candles on the cake, so was it meant to be a secret. I know she’d have enjoyed the joke.

Early the next morning, at 4.10 am, while most of those on board were asleep, a Japanese torpedo slammed into the hull of the Centaur. The ship exploded in a huge ball of fire and sank within three minutes. It had been passing North Stradbroke Island just off the southern Queensland coast.

Anne and 10 of her AANS colleagues were among the 268 people who lost their lives in the fireball or subsequently drowned. Of the nurses, only Nell Savage survived. She earned the George Medal for the courage and devotion to duty she demonstrated in the aftermath of the sinking.

IN MEMORIAM

At lunchtime on Friday 6 August 1943, a simple ceremony took place at Sunshine Harvester Works to honour Annie’s memory. Mr. V. H. McKay, the factory manager, spoke of Anne’s qualities and of her sacrifice, after which one minute’s silence was observed. Mr. McKay then unveiled an enlarged coloured portrait of Anne in her AANS uniform, which was subsequently hung in the first-aid room as a lasting memorial. The inscription on the photo reads:

From the employees of the Sunshine Harvester Works in grateful memory of Matron Anne Jewell, who for seven years served as a Nursing Sister in the Casualty Room. Died in the service of her country aboard A.H.S. Centaur, 14th May, 1943.

In memory of Anne.

SOURCES

- Ancestry.

- Digger History (website), ‘Sea Transport Staff, 1941–1945.’

- Goodman, R. (1992, 2016), Hospital Ships, Boolarong Press.

- Goossens, R., SS Maritime (website), MS Oranje.

- Howlett, L. (1991), The Oranje Story, Oranje Hospital Ship Association.

- Milligan, C. and Foley, J. (1993), Australian Hospital Ship Centaur: The Myth of Immunity, Nairana Publications.

- National Archives of Australia.

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS AND MAGAZINES

- The Argus (Melbourne, 9 Jan 1896, p. 5), ‘New Insolvents.’

- The Armidale Express and New England General Advertiser (NSW, 27 Aug 1930, p. 4), ‘Personal.’

- The Australian Women’s Weekly (29 May 1943, p. 9), ‘Men of Centaur Mourn Loss of Gallant Nurses.’

- The Daily News (Perth, 23 July 1910, p. 11), ‘My Letter Bag.’

- The Daily News (Perth, 21 Aug 1923, p. 2), ‘Obituary’

- The Daily News (Perth, 19 May 1943, p. 12), ‘Fewer Deaths On Centaur.’

- The Daily News (Perth, 15 Feb 1949, p. 7), ‘Hurt Man 82 Is Ex-Race Cyclist.’

- The Narrogin Observer (WA, 2 Jul 1927, p. 3), ‘Wickepin.’

- Sunday Times (Perth, 16 Jan 1916, p. 11), ‘Honorable Mention.’

- Sunshine Advocate (17 Jul 1936, p. 1), ‘Farewell To Sister Jewell.’

- Sunshine Advocate (13 Aug 1943, p. 1), ‘Memorial to Centaur Victim.’

- The Telegraph (Brisbane, 20 May 1943, p. 2), ‘All on Centaur Non-Combatants.’