AANS │ Sister Group 2 │ Second World War │ Malaya │ 2/13th Australian General Hospital

Early Life

Alma May Beard was born on 14 January 1913 at ‘Pell Mell,’ the family farm near Culham, in Toodyay district, Western Australia. She was the daughter of Katherine Mary Brennan (1883–1960), of ‘Ballen Vane,’ Toodyay district, and Edward William Beard (1883–1966), of ‘Pell Mell.’ Edward was the third generation of Beards to live at ‘Pell Mell,’ whose homestead block had originally been selected by his grandfather William in 1850.

Katherine and Edward were married at the Roman Catholic Church in Newcastle (as Toodyay was known until 1910) on 25 September 1907 and took up residence at ‘Pell Mell.’ They had five children, John Edward James (b. 1908), who died aged 20 months, Kathleen Louisa (b. 1909), Arthur John (b. 1910), Alma, and Doreen Alice (b. 1917).

In January 1924, just before Alma’s 11th birthday, a bushfire broke out in Culham district and within days had assumed a front of some nine kilometres. Many farms in the area of the fire affected, but ‘Pell Mell’ suffered the worst damage, with losses estimated at £1,000 or more. The fire destroyed the family’s crops, feed, chaffcutter and various tools, though the family home was unscathed. To make matters worse, Edward Beard had neglected to renew the insurance, which had expired just days before.

School

As a younger child, Alma attended Bejoording State School, where she demonstrated an aptitude for sport. At the Bejoording School Picnic held in October 1924, she came first in the Girls Under 11 race and consistently finished strongly in running events held at the various children’s picnics and parties she attended around this time.

Alma finished at Bejoording State School and began attending Toodyay State School, on Duke Street in Toodyay’s town centre. In December 1927, at the school’s annual prize day, she was awarded the Most Popular Girl in the School prize as well as the Grade VII General Proficiency prize.

In 1929 Alma moved to Perth to board at the Ladies’ College, located at the Convent of Mercy, Victoria Square. The school was opened by the Sisters of Mercy in 1896 and later became known as Our Lady’s College. In November of that year Alma was admitted to Toodyay Hospital and was operated on for appendicitis.

Nursing and Enlistment

In the mid-1930s Alma began to train as a nurse at Perth Public Hospital. She completed her training and became registered on 5 April 1939. Shortly after 20 September 1940, Alma moved to Sydney to take up a position in one of the hospitals.

By now war had broken out in Europe. Having returned to Perth, Alma joined the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) and on 19 June 1941 enlisted in the Australian Military Forces. On 4 August she was called up for full-time duty and posted to the hospital at Northam Army Camp, 30 kilometres southwest of Culham.

Alma did not stay long at Northam, however. On 15 August she was seconded to the Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF) for overseas duty with the 2/13th Australian General Hospital (AGH) and assigned the rank of staff nurse. The 2/13th AGH was being raised in Melbourne following a request for a second AGH in Malaya to support the 2/10th AGH, which had sailed in February on the Queen Mary with the 5,000 troops of the 22nd Brigade, 8th Division and was based in Malacca.

While awaiting embarkation, Alma was attached to the 110th AGH in Perth. Here she met six more 2/13th AGH recruits, Sisters Eloise Bales and Vima Bates and Staff Nurses Sara Baldwin-Wiseman, Iole Harper, Minnie Hodgson and Gertrude McManus.

On 6 September the seven nurses were guests of honour at a morning tea arranged by the Sportsmen’s Organising Council for Patriotic Funds and held at the Hotel Adelphi. Lieutenant-Governor Sir James Mitchell presented each nurse with an initialled travelling rug to mark her impending embarkation. Five other AANS nurses were also present, all staff nurses – Frances Aldom, Betty Brooking, Mary Hardwick, Beanie Keamy and Gwen Martin. They were due to embark for the Middle East but had already been presented with travelling rugs. Present also was Matron Margaret Edis, Principal Matron (Western Command), who thanked the Sportsmen’s Council for arranging the function.

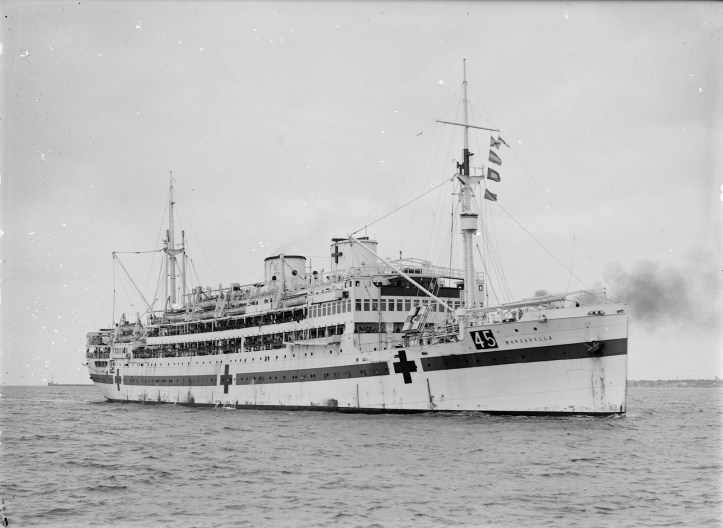

Wanganella

Alma and her six colleagues travelled to Fremantle on 9 September and boarded the Australian hospital ship Wanganella. On board they met around 40 other 2/13th AGH nurses and three masseuses, who had embarked in Sydney and Melbourne. Also on board were around 175 other staff members of the unit – surgeons, physicians, dentists, drivers, orderlies and others.

During the voyage the nurses spent their time teaching the orderlies bandaging and other basic nursing procedures. They attended lectures on tropical medicine and worked shifts in the sick bay. They enjoyed various sports and activities and became acquainted with their new colleagues. Some days after leaving Fremantle, the staff were officially told that they were bound for Malaya. Some expressed disappointment at the thought of being far from the ‘action.’ How wrong they were.

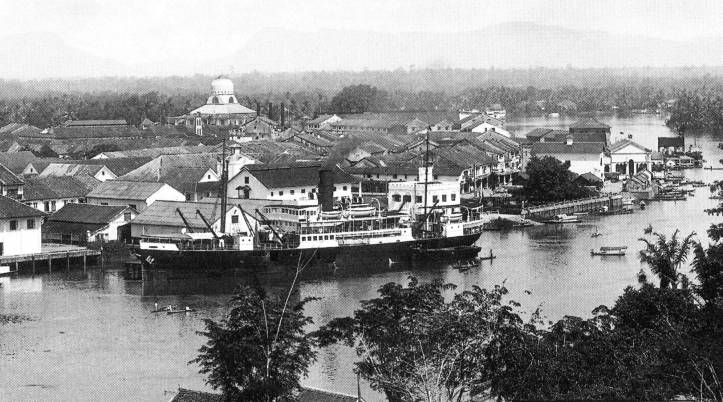

Singapore

The Wanganella arrived at Keppel Harbour on Singapore Island on 15 September. Ten of the nurses – dubbed the “mobile 10” by Tasmanian Mollie Gunton, who was one of them – were immediately detached to the 2/10th AGH to train in tropical nursing with their more experienced peers. After disembarking they were taken to a railway siding at Keppel Harbour and entrained for Tampin on the Malay Peninsula, from where they were taken by car to Malacca.

Meanwhile, the other 39, among them Alma, disembarked and were met by Colonel Wilfrid Kent-Hughes, Assistant Adjutant and Quartermaster General of the 8th Division, who had organised buses to transport them to St. Patrick’s School in Katong, on the island’s south coast. Here the 2/13th AGH would be billeted while waiting to be sent to its permanent base, a psychiatric hospital in Tampoi, in the south of the Malay Peninsula.

Until then, there would be no work at St. Patrick’s for the nurses. Instead, those not on detachment to the 2/10th AGH attended lectures, went on field trips to hospitals on the island, and continued to instruct their orderlies in general nursing techniques. They enjoyed plenty of leisure time, playing tennis and golf, and were granted access to the exclusive Singapore Swimming Club. They were taken to dinner and dances and on excursions by wealthy Singapore residents.

After the “mobile 10” returned to the 2/13th AGH on 6 October, a second contingent of nurses was detached to Malacca for three weeks, followed by a third. The 2/13th AGH nurses were also detached to the 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station (CCS). The 2/4th CCS had accompanied the 2/10th AGH on the Queen Mary in February and by 1 October had moved into the psychiatric hospital in Tampoi earmarked for the 2/13th AGH. In this rambling, single-story complex leased from the Sultan of Johor, the unit had established a small general hospital of 145 beds.

Tampoi

Alma was detached to the 2/4th CCS on 13 October and arrived at Tampoi the following day. The sprawling hospital complex was ringed around by a high iron fence and was somewhat grim. Hundreds of metres of covered walkways connected its disparate wings, and the nurses’ quarters were situated nearly a kilometre away. The hospital abutted jungle, and it was not unusual for scorpions, centipedes and other creatures to invade the wards. Nevertheless it was peaceful, a world away from the hustle and bustle of central Singapore. Moreover, it must have been satisfying for the nurses and other staff finally to be operating their own hospital.

On 21 November the 2/13th AGH finally received orders to move to Tampoi and over the next two days shifted 100 tons of equipment into the psychiatric hospital. The relocation was completed on 23 November and Alma rejoined her unit. Meanwhile the 2/4th CCS had moved north to Kluang, where it established its new hospital at the town’s aerodrome.

Invasion

The peace of Alma’s first three months was broken on 8 December, when the Imperial Japanese Army invaded Malaya. An amphibious assault on northern Malaya was followed a few hours later by the bombing of Singapore Island. In Tampoi the nurses could see Japanese planes flying overhead, seemingly immune to British anti-aircraft fire, and they could hear Japanese bombs exploding.

The Japanese army surged down the Malay Peninsula, forcing first British and Indian troops and then Australian troops to withdraw southwards. Soon the three AANS-staffed medical units had to withdraw too. In mid-January the 2/10th AGH was forced to relocate to Oldham Hall and Manor House on Singapore Island. By the night of 25 January the 2/13th AGH had followed suit, returning to St. Patrick’s School at Katong. By the end of January even the doughty 2/4th CCS had moved to the island.

Alma’s Letter

Sometime before the 2/13th AGH’s return to Singapore Island, Alma sent a letter to her parents, an extract of which was printed in the Toodyay Herald on 13 February 1942, as follows:

I’m afraid I’ve been a bit lax in writing home lately, but we’re very busy and when we come off duty at night it’s a black-out, so I can’t see to do any writing. We have broken time during the day. Since starting this letter I fell asleep despite air activity, and have just awakened to an “all clear” siren. By this you will have gathered that I am off night duty at last, but haven’t made up for loss of sleep yet. Fancy your having such a heavy storm. I wonder if its part of what we’re having here. Ours is an every day occurrence. I’ve lived in my gun boots [sic], raincoat and tin hat while out of doors the last few days. Fortunately the nights are cool and we are able to get a good sleep. I started this letter on Thursday, it is now Sunday, Iole and I are having the day off, so I have a chance to attend to my correspondence. I can hear planes coming over. I may have to dive for a slit trench at any moment, but as they are not very comfortable, I shall just watch proceedings from the verandah. It’s over for a while – “good show.” We don’t go to Singapore now; my last trip was on Monday last. We may be able to go later on. I get an absolute kick out of the sound of the A.A.C. guns, planes, etc. It positively fascinates me. They’ve started up again. I’ve seen only a couple of dog-fights so far, which is a poor show. I’d love to see a really decent one. You will guess by now that we’ve never been close enough to be scared or I wouldn’t be loving it so much. We can easily tell our planes from the enemies, and as we know some of the lads we say here comes Fred or Bill. The lads that have come in as patients are marvellous, and full of good spirits despite injuries etc., and of course no story loses anything in the telling. We are having a little party tonight, so I’ll give you a toast. Look after yourselves, don’t worry and keep your chins up. If you don’t hear from me often, you’ll know it’s because I’m terribly busy.

Evacuation

The Japanese advance was unstoppable. In early February the last Allied troops had crossed Johor Strait to Singapore Island, and holes had been blown in the Causeway. This action brought eight days’ respite. On 8 February, despite strong opposition from the Australians, Japanese troops crossed Johor Strait and established a bridgehead on the island. Singapore was doomed.

By now St. Patrick’s School was so overcrowded with Australian and Allied casualties that outbuildings and even tents were used as wards. The wounded lay closely packed on mattresses on floors or even outside on the lawns. And all the while, from outside the school came the noise of artillery fire.

On 9 February, in response to Japanese atrocities in Hong Kong, Major General Gordon Bennett ordered the evacuation of the 130 AANS nurses in Singapore. Unsurprisingly, the nurses did not want to leave their wounded patients and refused to volunteer. In the end, Alma and her colleagues had to be ordered to leave by the senior matron in Malaya, Dot Paschke of the 2/10th AGH. Many nurses wept as they went about their work on these final days in Singapore.

Six AANS nurses of the 2/10th AGH left Singapore on the Wusueh on 10 February. The following day, 60 more, 30 from each of the AGHs, got away on the Empire Star, including Alma’s fellow Western Australians Sara Baldwin-Wiseman, Eloise Bales and Gertrude McManus.

Vyner Brooke

On Thursday 12 February, Alma and her remaining 64 colleagues embarked on a small coastal steamer, the Vyner Brooke, which was carrying perhaps 200 evacuees, and in the gathering dusk the ship steamed slowly out of Keppel Harbour heading for Batavia. As the Vyner Brooke departed, several of the nurses looked back at the waterfront to see a city ablaze.

Over the next two days the Vyner Brooke made only slow progress. The ship’s captain, Richard Borton, moved during the night, safe from Japanese spotter craft, and during the day anchored close to islands. Then, at around 2.00 pm on Saturday 14 February, as the ship was approaching the entrance to Bangka Strait, Japanese dive bombers approached. The planes grouped into two formations of three and flew towards the ship. A series of near misses during the bombers’ first run was followed by three direct hits during the second. The Vyner Brooke lifted and rocked with a vast roar when the first exploded amidships. The next went down the funnel and exploded in the engine room. Then, as the passengers swarmed up to the open air, a third dealt the ship a last fatal blow. With a dreadful noise of smashing glass and timber, the Vyner Brooke shuddered and came to a standstill. It was lying 15 kilometres from Bangka Island.

The nurses carried out the plan they had discussed the previous day. They helped the women and children, the oldest people, the wounded, and their own injured colleagues into the three viable lifeboats, which were then lowered into the sea. One capsized upon entry into the water. Greatcoats and rugs were thrown down to the remaining two, which got away as the ship began to list alarmingly to starboard. After a final search of the ship it was the nurses’ turn to evacuate. They removed their shoes and their tin helmets and entered the water any way they could. Some jumped from the railing on the portside, others practically stepped into the water on the listing starboard side, others slid down ropes or climbed down ladders.

Bangka Island

Somehow Alma made it to shore, possibly in one of the two lifeboats that reached the shores of Bangka Island late on Saturday night. She joined a large group of AANS nurses and civilians around a bonfire on the beach. Later, more survivors of ships sunk by Japanese forces in Bangka Strait reached shore and joined the party around the bonfire. There were many wounded among them.

Sunday passed by, and on Monday it was decided that the group should surrender en masse to Japanese authorities. A deputation left for the nearest large town, Muntok, to negotiate this. A short while later most of the civilian women and children of the group followed behind, but the Australian nurses were duty-bound to remain with the wounded on the beach.

By mid-morning the deputation had returned with a group of Japanese soldiers. The soldiers separated the men from the women and led them around a bluff in two groups before shooting them.

The soldiers returned to the nurses and the remaining civilians. They ordered the nurses and at least one civilian women to advance into the water and form a line, facing the sea. They shot them as they stood there, looking out to sea, knowing their fate.

Alma and 20 colleagues died on Bangka Island on 16 February 1942. One colleague, Staff Nurse Vivian Bullwinkel of the 2/13th AGH, miraculously survived.

Twelve of the 65 AANS nurses who had set out from Singapore were lost at sea when the Vyner Brooke was sunk. Twenty-one had died on Radji Beach. Thirty-two nurses were made prisoners of war, of whom eight died. On 16 September 1945, after three and a half years of captivity, the surviving 24 nurses were flown to Singapore, and in October they arrived home in Australia.

Soon after, Vivian Bullwinkel wrote to Alma’s mother. As quoted in the West Australian newspaper on 30 October 1945, she said that Alma’s “brave conduct in her hour of crisis has added lustre to the service which she so nobly carried on.”

In memory of Alma.

SOURCES

- Angell, B. (2003), A Woman’s War: The Exceptional Life of Wilma Oram Young AM, New Holland Publishers.

- Australian Broadcasting Corporation (16 Feb 2022), ‘Memorial honours Wheatbelt nurse on the 80th anniversary of her death on Bangka Island during WWII.’

- Australian War Memorial (11 February 2019), ‘The Last Post Ceremony commemorating the service of (WFX11175) Sister Alma May Beard, 13th Australian General Hospital, Royal Australian Army Nursing Service, Second World War.’

- Carnamah Historical Society and Museum, ‘Western Australian Nurses 1919–1949’.

- Simons, J. E. (1956), While History Passed, William Heinemann Ltd.

SOURCES: Newspapers

- The Daily News (Perth, 6 Sep 1941, p. 7), ‘AIF Nurses Get Due Praise’.

- Newcastle Herald and Toodyay District Chronicle (WA, 5 Oct 1907, p. 6), ‘Wedding.’

- Toodyay Herald (WA, 19 Jan 1924, p. 2), ‘Big Bush Fire.’

- Toodyay Herald (WA, 23 Dec 1927, p. 2), ‘Prize Distribution.’

- Toodyay Herald (WA, 22 Nov 1929, p. 2), ‘Notes of Interest.’

- Toodyay Herald (WA, 20 Sep 1940, p. 4), ‘Society Siftings.’

- Toodyay Herald (WA, 16 Jun 1944, p. 1), ‘Vale, Lieut. Alma May Beard.’

- Toodyay Herald (WA, 26 Oct 1945, p. 1), ‘Personal.’

- Toodyay Herald (WA, 16 Apr 1948, p. 3), ‘Five Generations of Beard Family.’

- The Weekly Gazette (Goomalling, 24 Oct 1924, p. 2), ‘Bejoording News.’

- The West Australian (Perth, 29 May 1937, p. eight), ‘To Say Au Revoir.’

- The West Australian (Perth, 30 Oct 1945, p. 7), ‘Woman’s Realm.’