VAD │ First World War │ Australia & England

FAMILY BACKGROUND

Kathleen Adele Brennan, known as Adele, was born on 15 November 1882 at ‘Farleigh’ on Point Piper Road in Woollahra, an inner eastern suburb of Sydney.

Adele’s mother, Elizabeth Mary Keating (1858–1924), was born in Penrith, Sydney. Adele’s father, William Francis Brennan (1849–1924), was born in Woollahra. He was educated at Lyndhurst College and became a solicitor, admitted to practice in 1875. He practised on King Street in Sydney and later moved to Pendennis Chambers on George Street.

Elizabeth and William were married on 9 June 1880 at St. Mary’s pro-Cathedral in Sydney and settled at ‘Farleigh.’ In March 1881 Elizabeth gave birth to their first child, Florence Mary. After Adele’s birth in 1882, the Brennans moved to Avoca Street in Randwick, where Francis William, known as Frank, was born in August 1884. He was followed in April 1886 by William Keating. The family then moved to ‘Clareinnis’ on the Boulevarde in Strathfield, inner-west Sydney, and in April 1896 John Clive, known as Jack, was born.

GROWING UP

Adele enjoyed a middle-class Catholic upbringing. She and Florence learned pianoforte under a Miss Donovan, and in October 1893 took part in a concert put on by Miss Donovan’s pupils at the Glebe Town Hall. Adele played the minuet from Boccherini’s 11th String Quintet and selections from ‘Faust,’ while Florence played Mendelssohn’s ‘Wedding March.’

Adele, Florence and Frank went to school at nearby Santa Sabina Dominican Convent, located close to Clareinnis on the Boulevarde. At the 1895 end-of-year awards ceremony, Adele was given a prize in French. Florence was awarded several prizes.

In the later 1890s the Brennans seemingly returned to the eastern suburbs, perhaps now to ‘Floradel’ on Edgecliff Road in Woollahra. In 1899 Adele was a pupil at the Sacred Heart Convent in Rose Bay. She had learned to play the violin, and on Christmas Day 1899 she and three other pupils of the convent played Handel’s ‘Largo’ at High Mass at St. Mary’s Cathedral.

On 11 September 1901 Adele, now nearly 19 years old, made her debut at the Australian Club Ball, held at the Sydney Town Hall. Thereafter she entered society, and like her mother devoted much of her time to civic and charitable activities. Among other things, she later became a member of the Rose Bay Association and by January 1916 was one of two honorary treasurers of the association.

WAR

In August 1914 Australia entered the Great War. All five Brennan children wanted to serve. However, they agreed that one daughter and one son should remain in Australia to look after their parents, who were by now getting on. Florence and Frank stayed. William, Jack and Adele volunteered.

Lieutenant William Brennan served with the 12th Australian Light Horse. He was killed in Palestine on 20 April 1917 and was buried at the Gaza Military Cemetery. Lieutenant Jack Brennan served with the 4th Battalion. He was wounded in France but survived the war and returned to Australia in June 1919.

Adele served with a Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD), first in Australia, then in England.

VOLUNTARY AID DETACHMENTS

Voluntary Aid Detachments originated in England in August 1909 when the War Office proposed a scheme whereby, in the event of war, volunteers (or Voluntary Aids – VAs) would provide aid to sick and wounded soldiers along the line of evacuation from field ambulance to general hospital. The British Red Cross Society, via its county associations, would organise VAs into village-based detachments. Each detachment would comprise two complete half detachments, one of men, the other of women. The men would deal with transport and logistics and would also act as stretcher bearers and to a certain extent male nurses. There would also be specialist carpenters, mechanics, clerks and sanitary workers.

The women would form railway rest stations, prepare and serve meals and refreshments, and take temporary charge of patients unable to continue their journey. They would therefore be trained in the preparation of invalid diets, in arranging small wards, and in the basics of first aid and nursing. In brief, as the Brisbane Telegraph put it on 2 October 1909, “an opportunity will be given to every woman to act as a nurse in time of invasion.”

Each women’s detachment would consist of a commandant and an assistant commandant, both of whom would be medical officers (and presumably men); a quartermaster and an assistant quartermaster (also presumably men); two lady superintendents; and 20 women, 18 of whom would have a St. John Ambulance first-aid certificate, while the other two would be fully trained nurses. All would be expected to work equally. They would wear no uniform – simply a broad white band on the arm with the red cross on it. Nevertheless, they, like their male VAD colleagues, would be members of the Territorial Army.

LADY HELEN MUNRO FERGUSON

Lady Helen Munro Ferguson had been in Australia for less than a month when the war began. She was the wife of the new governor-general and had been heavily involved in the Red Cross movement in Scotland and now proposed establishing a federated branch of the British Red Cross Society in Australia. At the same time, she called for the formation of Red Cross branches across Australia – and, bringing to bear her knowledge of British VADs, proposed that among other tasks the branches enrol suitable men and women for allocation to local VADs.

Meanwhile, for its part, the Commonwealth moved quickly to approve the formation of Australian VADs. Women’s detachments would be based on the British model but differ in composition and to some extent in duties. They would consist of one commandant and one quartermaster (both of whom would be women), one trained nurse as lady superintendent, and 20 women, of whom four would be qualified cooks. With the exception of trained nurses and cooks, each VA would have first aid and home-nursing certificates or undertake to gain such certificates within 12 months from the date of enrolment.

The women VAs would carry out menial but essential tasks. Essentially fulfilling the role of (male) nursing orderly, they would, among other tasks, scrub floors, sweep, dust and clean bathrooms and other areas, deal with bedpans, and wash patients. They would work in Red Cross rest homes and civilian hospitals, in canteens, on troop trains, etc. They would not be employed in military hospitals, except as ward and pantry maids.

In time, Adele joined the St. Vincent’s Hospital Detachment in Darlinghurst.

THE FIRST AUSTRALIAN DETACHMENT

Initially, the Commonwealth did not permit the overseas deployment of Australian VADs. As a result, many individual women VAs chose to travel to England on their own initiative, where they joined British detachments and sometimes found themselves working in Australian military hospitals.

This situation changed in 1916. By then, the demand on women’s labour in England was considerable, with thousands taking part in munition works and in agriculture. It was agreed that the countries of the Empire should be called upon to send women’s VADs.

Consequently, in June 1916 the chairman of the Joint War committee of the British Red Cross Society and the Order of St. John cabled Lady Munro Ferguson from London asking her to find 30 members of Australian women’s VADs who were willing to serve as probationers in military hospitals in England. Each Voluntary Aid had to be between the ages of 23 and 38, hold the usual certificates for first aid and home nursing, and have good health and a good education. She would receive £20 per year with an additional grant of £4 for her uniform, payable by the British authorities, and was expected to serve for between six and eight months in England.

Upon receipt of the cable, Lady Munro Ferguson wrote to the state committees of the Australian Red Cross and requested the following allocations: 10 VAs from New South Wales, nine from Victoria, two from Queensland, three from Tasmania (one from the north, two from the south), and three each from South Australia and Western Australia.

Over the next two months, the 30 VAs were chosen from among hundreds of candidates across Australia.

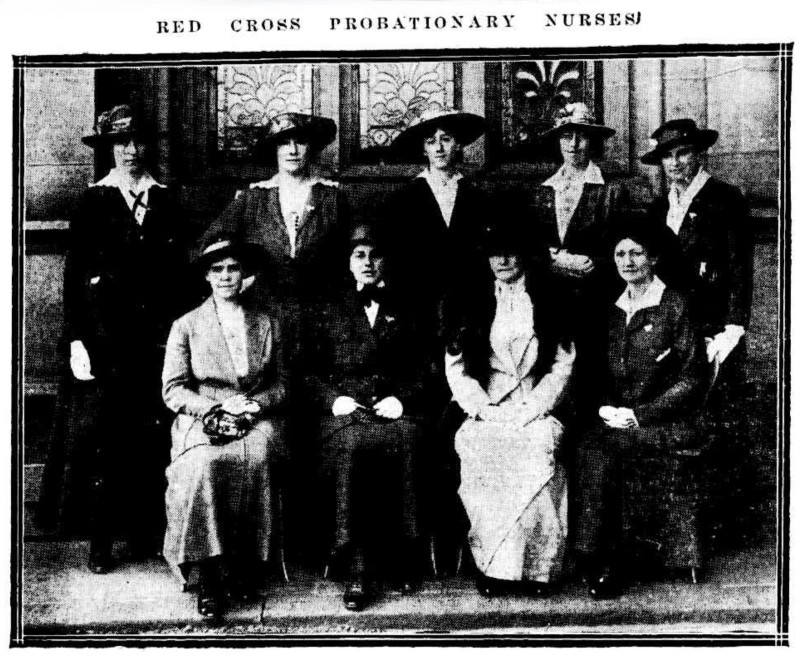

Adele was among the New South Wales contingent. The others were Beatrice (‘Trixie’) Bruce Smith, acting commandant, from the Bowral VAD; Edith Stevenson (Moss Vale VAD); Enid Armstrong (Headquarters VAD); Louie Black, Kathleen Giblin and Mary McAlister (Roseville VAD); and Nancy Hill, Edith Louise (‘Lulu’) Leary, and Miss Stead – who, together with Adele, belonged to the St. Vincent’s Hospital VAD.

Front Row: Louie Black, Trixie Bruce Smith, Mrs Christopher Bennett (Assistant Director of Voluntary Aids), Miss Stead. (The Sydney Morning Herald, 25 Sept 1916, p. 5)

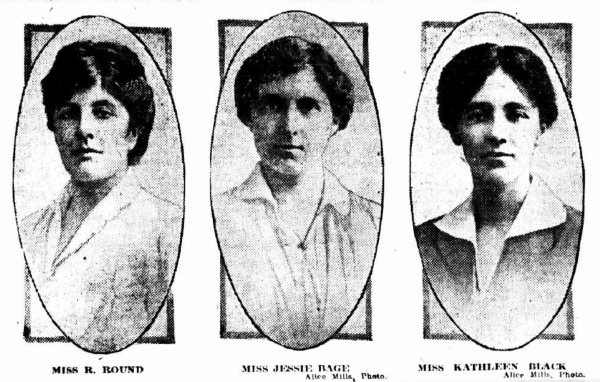

The nine Victorians were Jessie Bage, Kathleen Black, Millie Cox, Doris Fuller, Doris Marshall, Margaret Moore, Dorothy (‘Dolly’) Pitt, Ruby Langford Round, and Dorothy Swallow. Six of the nine had trained under Matron Davies at the No. 1 Red Cross Rest Home, Wirth’s Park (located where Arts Centre Melbourne and the NGV now stand). According to Punch newspaper on 28 September 1916, the nine Victorians “unanimously voiced the opinion that they thoroughly realise they are not going ‘home’ for a picnic, but hard work (with a capital W.) lies ahead of them; and they are not a bit afraid of the strictness of British military discipline which seems to rather overawe all Australians who come in contact with it for the first time.”

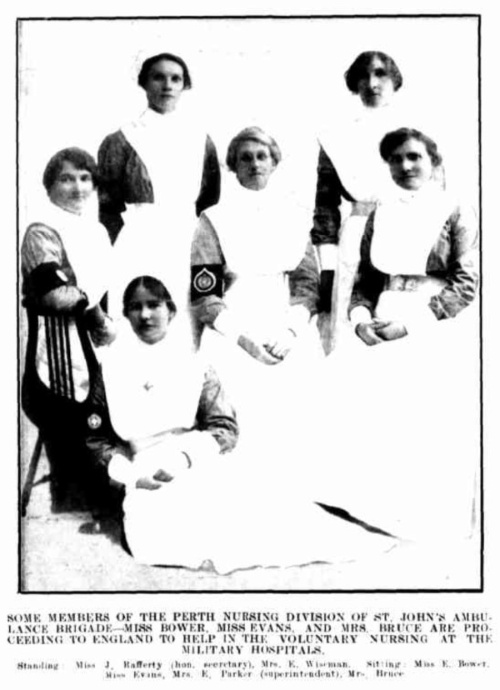

From Queensland were Jean Darvall and Lydia Grant; from Tasmania Etta Douglas (Northern VAD) and Eileen Bailey and Miss Fisher (Southern VAD); from South Australia Rosey Bennett, Ethel Hall and Olive Hiles; and from Western Australia Emma Bower, Mrs Lydia Bruce and Ida Evans, who were all selected from the Perth Nursing Division of the St. John Ambulance Brigade.

The detachment of 30 VAs would sail to England on the P&O liner RMS Osterley in early October.

RMS OSTERLEY

The two Queensland VAs boarded the Osterley in Brisbane and on 16 September 1916 began their journey to England. Soon the Osterley arrived in Sydney and tied up at Orient Wharf at Circular Quay. Adele and the rest of the New South Wales contingent boarded, and the ship sailed on 23 September. It called into Port Melbourne, where the Victorians and Tasmanians boarded, and left again on 27 September. The three South Australians departed Port Adelaide on 29 September, and the Osterley arrived in Fremantle.

At 4.00 am on 4 October the Osterley departed Fremantle and sailed across the Indian Ocean to Durban and then Cape Town. In early November the ship called at Plymouth before arriving at Gravesend in London on 10 November. A cable advising of the Osterley’s safe arrival was sent to authorities in Australia.

(Three years later it was reported that during the voyage, the captain learned that a German spy was on board. Several passengers, among them Enid Armstrong, were allotted as ‘watchers’ and kept an eye on the man. Shortly before the ship’s arrival at Plymouth, the spy was caught attempting to carry out an act of sabotage and was shot. Before he died, he told the captain that bombs had been planted in the coal bunkers, timed to go off within 24 hours. They were found and disarmed. The story came to light in July 1919 upon Enid’s return to Australia.)

ENGLAND

On arrival in London, Adele and the other New South Wales VAs (and possibly some or all of the others) were sent to the Queen Mary’s Hostel for Nurses, and soon they began to be allotted to their military hospitals. The New South Wales VAs were posted to the 5th Northern General Hospital in Leicester. The hospital had a number of branches, and Adele, Enid Armstrong and possibly Mary McAlister and Edith Stevenson were sent to North Evington War Hospital. They reported for duty on 18 November.

On 10 December one of the Victorians, Ruby Langford Round, wrote home from the Independent College on College Road, Whalley Range, Manchester. An extract of her letter was printed in the Launceston Examiner on 17 February 1917 (as below). We cannot be sure, but her experiences were quite possibly similar to those of Adele and the others.

At last I have started a letter to you. The days seem to pass so swiftly that I never manage to catch up to my correspondence. Well, after five very busy but enjoyable days spent in London, eight of us were despatched to this city – a dingy, smoky place – to the No. 2 Western General Hospital – a very large centre, with over 40 branches and 28,000 beds. I am working at one of the branches, Leaf Square Military Hospital, Pendleton, a suburb of Manchester. We have 250 beds at our place, with only eight sisters and ten nurses and six orderlies to do all the work, including X-ray operations and inoculations, so you can guess we are kept always hurrying, which keeps us warm, anyway. So far I have not felt the cold a scrap, though this is supposed to be a particularly damp and cold part of England. The work is very interesting, as, owing to the shorthandedness, we newcomers are put on to advanced work straight away, such as assisting with dressings, even doing some minor ones entirely ourselves, preparing patients for operations, etc., and only do the drudgery part of nursing when we have a few minutes to spare. You see, as soon as ever the men are convalescent they are sent off to convalescent homes, and we get a fresh batch of patients from one of the hospital trains, so never get a change to be slack. Some of the wounds that we get to attend to are just awful; the poor fellows must suffer agonies at each dressing, but never complain, and are so grateful for all that is done for them. The residents here seem to take very little interest in these military hospitals, and very few comforts are sent here, and we are kept on very short rations by the authorities. But everywhere they are feeling the pinch of the war here now. We in Australia had nothing to grumble at, though we often did. It must be an awful struggle to provide meals on a fixed amount, for prices are rising every day. Eggs are 6d and 8d each, cheese 1s 6d a pound, meat 2s 1d a pound, butter, 2s 8d a pound, jam 8d a pound, and so on. We get enough to eat, but very plain – often no sugar for a week, never butter, but always margarine, and for breakfast only bacon and bread and tea, that is all. Still, we all feel splendid, in spite of our long hours. As there is no accommodation for us at the hospitals, we are all billeted at a large college, and have to travel to and fro each day – over an hour’s journey each way. We rise at 6.15 a.m., have a cup of tea, and leave before 7, go on duty at 8 a.m., have two hours off during the day, and leave some time after 8 p.m., arriving home about 9.30, quite ready for a bath and bed. The latter spot is where I am now scribbling this, so hope you can read it. If not too busy, we get a half-day off a week, but I have only had one so far. We have a uniform, much the same as we wore at the Rest Home (Red Cross Rest Home No. 1, Melbourne), except that our caps are different. Out of doors we wear a long navy blue coat, with black buttons, white gloves, and navy blue felt hat with blue and white band – very nice and comfortable. I did not bother to get many new clothes when I found we had to wear outdoor uniform as well. There is only one other Victorian here with me – Miss Swallow. The others are two Queensland, two Tasmanian, and two South Australian. The rest of the Victorians went to King George’s Hospital, Waterloo, London. The N.S.W.’s went to Leicester, and the W.A.’s to Leeds. Our commandant and vice-commandant were lucky enough to go to Rouen. I hope to get across to France later, but will have to remain here for six months first.

FINAL DAYS

Adele remained in Leicester for the next two years. Unfortunately, we know nothing at all of her experiences over this time – save at the very end.

It is a terrible tragedy that after so happy an occasion as the end of the war on 11 November 1918, and after two years of dedicated, selfless service, Adele should have become gravely ill, but that is what happened. After contracting influenza, she died of septic pericarditis at North Evington War Hospital on Sunday 24 November 1918.

Adele was buried with full military honours on 26 November 1918 in the soldiers’ corner of Welford Road Cemetery in Leicester.

The coffin, covered with the Union Jack, was borne to the cemetery on a gun carriage, followed by a large procession of medical and nursing staff, including fellow VAs, from North Evington and the other branch hospitals of the 5th Northern General. The cortege was met at the cemetery by the Reverend Father Lindeboom, who led the procession to the soldiers’ corner, and here Adele was interred close to the graves of Australian soldiers. Adele’s brother Jack was present, as were three of her fellow Australian VAs – perhaps Enid Armstrong, Mary McAlister and Edith Stevenson. A party from Glen Parva Barracks fired volleys over the grave, and the ‘Last Post’ was sounded by Royal Army Medical Corps buglers.

POSTSCRIPT

In 1921 William Brennan, nearing the end of his life, wrote to Australian military authorities concerning memorials for his son William, who was killed in Palestine, and for Adele. In his letter he stated that Adele “qualified [at North Evington] as an assistant nurse [and] was mentioned in despatches.”

In memory of Adele.

SOURCES

- Australian War Memorial, ‘Voluntary Aid Detachments.’

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission, News (11 May 2018), ‘CWGC remembers the brave nurses lost during the world wars on International Nurses Day.’

- Find a Grave, ‘Nurse Kathleen Adele Brennan.’

- Kincoppal-Rose Bay School of the Sacred Heart, Alumnae Stories (From the Archives, 19 Apr 2022), ‘Lest we Forget – Adele Brennan (RB 1900).’

- The Long, Long Trail (website), ‘Military hospitals in Leicestershire.’

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS

- The Age (Melbourne, 5 Aug 1916, p. 3), ‘Appeal for Nursing Aid. Military Hospitals in England. Probationers from Australia.’

- The Age (Melbourne, 1 Sept 1916, p. 6), ‘Red Cross Society.’

- The Argus (Melbourne, 31 Aug 1916, p. 8), ‘Vice-Regal.’

- The Argus (Melbourne, 6 Sept 1916, p. 7), ‘Red Cross Society.’

- The Argus (Melbourne, 23 Sept 1916, p. 8), ‘Woman’s Realm.’

- Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, 21 Sept 1901, p. 45), ‘Australian Club Ball.’

- The Brisbane Courier (18 Jul 1916, p. 7), ‘Red Cross Society.’

- The Catholic Press (Sydney, 21 Dec 1895, p. 10), ‘Dominican Convent, Santa Sabrina, Strathfield.’

- Daily Commercial News and Shipping List (Sydney, 14 Nov 1916, p. 14), ‘Shipping Review.’

- The Daily News (Perth, 4 Oct 1916, p. 4), ‘Shipping.’

- The Daily News (Perth, 12 Dec 1918, p. 3), ‘Mainly About People.’

- Daily Telegraph (Launceston, 17 Aug 1916, p. 7), ‘Social Notes.’

- The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, 21 Sept 1916, p. 9), ‘For Women.’

- The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, 2 Oct 1909, p. 19), ‘Woman’s Letter from London.’

- Evening News (Sydney, 12 Apr 1881, p. 2), ‘Family Notices.’

- Examiner (Launceston, 17 Feb 1917, p. 9), ‘V.A.D. Workers.’

- Freeman’s Journal (Sydney, 23 Dec 1899, p. 10), ‘Woman’s Page.’

- Freeman’s Journal (Sydney, 20 Jan 1916, p. 26), ‘Woman’s Page.’

- Freeman’s Journal (Sydney, 10 Aug 1916, p. 26), ‘In the Winter Garden.’

- Freeman’s Journal (Sydney, 12 Dec 1918, p. 32), ‘In the Winter Garden.’

- Freeman’s Journal (Sydney, 6 Mar 1919, p. 18), ‘The Gossip of the Week: Round about Australia.’

- The Herald (Melbourne, 19 Sept 1916, p. 5), ‘Red Cross Nurses Will Work in England.’

- Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate (NSW, 25 Aug 1916, p. 7), ‘An Idle Woman’s Diary.’

- Punch (Melbourne, 28 Sept 1916, p. 29), ‘Fact and Rumour.’

- Punch (Melbourne, 28 Sept 1916, p. 34), ‘The Ladies Letter.’

- Queensland Times (Ipswich, Qld., 24 Sept 1909, p. 8), ‘Red Cross in Every Home.’

- The Sun (Sydney, 11 Nov 1916, p. 5), ‘Men and Women.’

- The Sun (Sydney, 15 Nov 1916, p. 5), ‘Australians in London.’

- Sunday Times (Sydney, 10 Oct 1909, p. 21), ‘Voluntary Aid Detachments in England.’

- The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW, 12 Jun 1880, p. 1), ‘Family Notices.’

- The Sydney Morning Herald (19 Oct 1893, p. 6), ‘Amusements.’

- The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW, 11 Aug 1914, p. 8), ‘Unifying Scheme.’

- The Sydney Morning Herald (10 Aug 1914, p. 11), ‘The Injured in War. Red Cross Detachments.’

- The Sydney Morning Herald (23 Sept 1916, p. 9), ‘Social.’

- The Sydney Morning Herald (10 Dec 1918, p. 8), ‘Late Miss Adele Brennan.’

- The Sydney Morning Herald (16 Jul 1919, p. 13), ‘A German Spy.’

- The Sydney Morning Herald (16 Oct 1919, p. 6), ‘Personal.’

- The Sydney Morning Herald (3 Jul 1924, p. 5), ‘Solicitor’s Death.’

- The Sydney Morning Herald (4 Nov 1924, p. 13), ‘Mrs. E. M. Brennan.’

- The Telegraph (Brisbane, 2 Oct 1909, p. 17), ‘Women as Territorials.’

- The West Australian (Perth, 15 Sept 1916, p. 6), ‘News and Notes.’