AANS │ Staff Nurse │ First World War │ Randwick Military Hospital & Woodman’s Point Quarantine Station

EARLY LIFE

Ada Mildred Thompson was born in 1885, around July, in the district of Dubbo, New South Wales. She was the daughter of Mary Anne Cowley (1852–1935) and William Grundy Thompson (1835–1918), who were married around 1875. Each had (apparently) been married previously, twice in William’s case.

Details of Ada’s early life are difficult to pin down. She had six siblings and (possibly) eight half-siblings. She may have attended Brocklehurst Public School or Dubbo Public School. In 1900 she was staying with members of her family at Rio Park in Bulyeroi district, 300 kilometres north of Dubbo. In that year her sisters Rose and Lilly married two brothers from Bulyeroi, respectively Stanley and Harry Greenaway.

In the early 1910s Ada began nurses’ training at the Royal North Shore Hospital in Sydney and passed her Australasian Trained Nurses’ Association membership examination in June 1915. By then war had broken out in Europe, and thousands of Australian nurses had volunteered for service with the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS). In time Ada would be one of them.

ENLISTMENT

Ada joined the AANS and on 17 October 1917 signed her attestation form for overseas service with the Australian Imperial Force (AIF). At the time, her mother, whom Ada nominated as next of kin, was living at ‘Wytona’ in Pallamallawa, 130 kilometres northeast of Bulyeroi, near Moree.

Sometime following her enlistment, Ada was posted to the Randwick Military Hospital in Sydney, which was established upon the outbreak of war in August 1914 and occupied buildings formerly belonging to the Asylum for Destitute Children and the Catherine Hayes Hospital. She was there in October 1918 when at last she was called up to the AIF as a reinforcement staff nurse for service in Salonika, northern Greece. She would sail via South Africa to England, from where they would transship for Salonika.

The Allies had recently launched an all-out offensive against Bulgarian forces in northern Greece, and even though by 30 September Bulgaria had been defeated, there were many thousands of Allied casualties in Salonika still requiring treatment. Many thousands more were suffering from malaria. Just four days before Ada’s departure, this dread disease claimed the life of AANS nurse Gertrude Evelyn Munro while she was a patient at the 43rd British General Hospital in Salonika.

THE WYREEMA

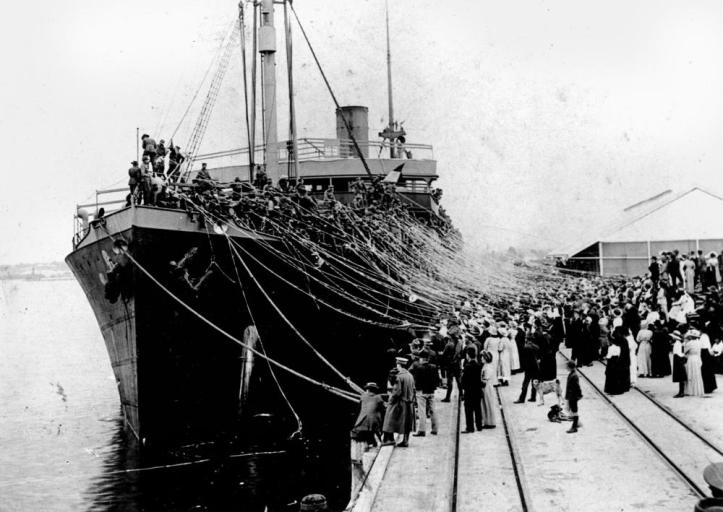

Ada enlisted in the AIF on 14 October, the day she was due to depart for overseas. She travelled from Randwick Military Hospital to Sydney Harbour and along with 36 other AANS reinforcement staff nurses boarded HMAT Wyreema, a coastal steamer requisitioned from northern Queensland for use as a troopship. Already on board the ship were around 700 AIF reinforcements from Liverpool Camp, 30 kilometres to the west of central Sydney. After alighting at Central Railway Station, they had marched to Woolloomooloo Bay, from where they were ferried out to the Wyreema.

At 4.00 pm the Wyreema drew away from the wharf and anchored off Potts Point, then at midnight set off on its voyage. It reached Fremantle on 22 October and entered port at around 4.30 pm. The nurses were granted shore leave and a group of them caught a train to Perth and stayed the night at the Esplanade Hotel.

The Wyreema departed Fremantle on the following day at around 5.00 pm. As it steamed away, boats at anchor in the harbour blew their whistles as their passengers waved flags and cooeed. During the voyage the nurses read, sewed, played cards and games on deck, attended church services, boat drills, dinners and concerts, and even staged a play.

At around 9.00 am on 8 November the Wyreema arrived at the small bay off the town of Durban, South Africa. Shore leave was forbidden due to an outbreak in the town of pneumonic influenza – the so-called Spanish flu. While at anchor in the harbour the ship was coaled by riggers working alongside on coal lighters, a process that continued into the following day and which covered everything – and everyone – in coal dust. On the morning of 10 November the ship pulled in alongside the wharf to take on water. Later, a few of the men jumped over the side of the ship and began swimming towards shore. They were brought back at around 5.00 pm, and at 5.30 pm the Wyreema, still covered in coal dust, drew anchor and sailed for Cape Town.

The following day was 11 November. Early that morning, in a clearing in the Forest of Compiègne in northern France, the Armistice that ended the fighting on the Western Front was signed in Marshall Foch’s railway carriage. At 11.00 am the guns fell silent and the Great War was over. News of the Armistice reached Australia later that day, and while naturally it was received with outpourings of joy, it presented logistical challenges. For example, what should be done with the troopships already en route to Europe?

In the early afternoon of 13 November, two days after the signing, the Wyreema dropped anchor in Table Bay, Cape Town. Once again shore leave was forbidden, as Cape Town was also gripped by influenza, and for days everyone was stuck on board doing the same things they had done during the voyage. On 19 November Rosa’s colleague Susie Cone, from Victoria, who kept a diary, noted that “the government don’t seem to know what to do with us.”

On Wednesday 20 November some of the nurses and officers from the troopship Borda came across to the Wyreema for lunch. After lunch the visit was reciprocated by some of those on the Wyreema. The Borda had arrived in Table Bay two days earlier from England and was en route to Australia with 1,000 Anzacs on board. Like those on the Wyreema, its passengers had not been allowed shore leave.

At long last the Wyreema received orders, and at 8.30 pm on 23 November it steamed out of Table Bay bound for Australia. Staying behind due to personal reasons were four of Ada’s AANS colleagues, Marguerita Mayor, Maude Rudall, Florence Holden and Cora MacNeil, along with some of the officers and men, and one of the ship’s padres.

As it sailed eastwards through the Indian Ocean, the Wyreema began to pick up radio messages from the troopship Boonah. Like the Wyreema, the Boonah had been on its way to the front and following the Armistice had spent more than a week in Durban before being recalled to Australia. Ominously, pneumonic influenza had broken out on board.

THE BOONAH

The Boonah was the last ship to leave Australia with troops for the front. It departed Port Adelaide on 22 October bound for England via Fremantle and South Africa. On board were around 1,000 AIF personnel, including some 30 members of the Australian Army Medical Corps. After leaving Fremantle on 30 October the ship steamed across the Indian Ocean and was three or four days out from Durban when the Armistice was signed.

The Boonah was ordered to continue to Durban. Upon arrival the soldiers found that they were not permitted shore leave – due, as we known, to the outbreak of influenza – and were forced to remain on board. After spending eight days in Durban harbour awaiting orders, coaling and discharging cargo, the Boonah set out for Fremantle on 25 November. That same day one of the soldiers or crew showed symptoms of influenza. Somehow the virus had been brought on board.

Some reports state that several soldiers and crew had disobeyed orders and gone ashore, while other reports suggest that local stevedores had infected crewmembers during the offloading of cargo. Regardless, as the days went by, the virus spread unchecked. Before long most of those on board had either contracted pneumonic influenza or were contacts of someone who had, and all the while the Boonah’s radio operator transmitted details of the daily increasing tally.

Meanwhile, the Wyreema, running one day ahead of the Boonah, was now approaching Australia. The officer in charge of the troops on board, Lieutenant Colonel P. M. McFarlane, who was aware of the influenza outbreak on the Boonah, was asked to call into Fremantle to land a number of AANS nurses to assist at the quarantine station at Woodman’s Point. At first daylight on 10 December the Wyreema arrived in Fremantle and dropped anchor in the harbour. Later that morning, after shore authorities signalled for 20 nurses to assist at the quarantine station, the ship’s matron called for volunteers. Twenty-six nurses offered, so their names were placed in a hat and 20 drawn out. Ada was one of them.

With Ada were Ethel Rachel Newby, Catherine Bevan Thomas and Mary Hay Walker from New South Wales; Doris Frances Bell, Margaret Bourke, Grace German, Naomi Higman, Jessie Scholes Hogg, Rosa O’Kane and Jane Selina Robson from Queensland; Vera Evalein Bradshaw, Grace Collins, Susie Cone, Maud Clow Hamilton, Nellie Mabel Manning, Stella Marie Morris, Lizzie Neil Scott and Gertrude Gordon Wilkinson from Victoria; and Harriet Jackson from South Australia. The nurses knew perfectly well the risk they were taking but were eager to help.

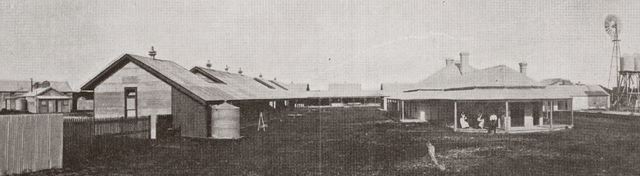

Ada and her colleagues left the Wyreema at 4.00 pm and were taken to Woodman’s Point, 10 kilometres south of Fremantle’s inner harbour. They arrived at the quarantine station tired and hungry, and after unpacking had a look around. Meanwhile, the Wyreema had continued on its way, and at 7.00 pm on Friday 20 December disembarked its troops at Port Adelaide’s Outer Harbour after three days’ quarantine at the anchorage.

QUARANTINE STATION

When the Boonah dropped anchor in Gage Roads, Fremantle’s outer harbour, early on the morning of Wednesday 11 December, it was ordered into strict quarantine, and the most severe cases began to be transported by tug to Woodman’s Point and admitted to the quarantine station hospital. Ada and the other nurses were ready and waiting when the first patients arrived at around 10.00 am. According to Susie Cone’s diary entry of that day, they were in a bad way. “Poor lads were in a terrible plight,” Susie writes. “Filth & dirt all over them terribly sick, we had no drugs, no clean shirts or pyjamas to put on them all we could do was to wash them & get them as comfortable as possible Three died the first day.”

Susie described the following day as hellish, with a shortage of drugs and food, but this situation improved on Friday. By the end of that day every influenza case had been disembarked from the Boonah – 337 cases out of around 1,000 – and the death toll stood at 10. On Saturday 14 December Rosa O’Kane of Queensland and Sister Leeds, a civilian nurse who had volunteered to work at the quarantine hospital, fell ill. Rosa’s condition worsened over the coming days, and more nurses came down with the virus. By 20 December Ada had contracted the virus too.

Rosa O’Kane died at 1.45 am on 21 December. In her final hours she had been comforted by Stella Morris, who had also contracted influenza, and nursed by Grace German, who had thus far remained well. Rosa was given a military funeral later that day. Meanwhile, in Adelaide that same day a contingent of 12 AANS nurses from the 7th Australian General Hospital (AGH) in Keswick set out for Fremantle. They arrived on Christmas Eve. Among them was a nurse by the name of Doris Ridgway.

By 30 December Ada was very ill, as was Hilda Williams, another of the civilian nurses. Hilda was a trainee of the Children’s Hospital in Subiaco and later trained in midwifery at the Women’s Hospital in Melbourne. She was working in private nursing in Claremont when she offered her services at the quarantine station.

On 31 December – New Year’s Eve – Ada’s condition was critical, and she died at 5.00 pm on 1 January 1919. She was buried the following day at the quarantine station cemetery. Tragically, inexplicably, her colleagues were not permitted to attend. Ada was later reinterred at Fremantle Cemetery.

Two more nurses passed away during this dreadful time, Hilda Williams on 4 January, and Doris Ridgway on 6 January. Staff Nurse Doris Alice Ridgway was from Salter’s Springs in South Australia. At the end of 1917 she completed her nurses’ training at Adelaide Hospital and immediately volunteered for service with the AANS. She was called up and on 24 August 1918 posted to the 7th AGH. After just four months’ service she had made the ultimate sacrifice.

As many as 28 soldiers lost their lives at Woodman’s Point.

In memory of Ada.

SOURCES

- Ancestry.

- Australian War Memorial, Unit Embarkation Nominal Rolls, 1914–18 War, ‘AWM8 26/100/1 – Nurses (July 1915 – November 1918).’

- State Library of New South Wales (Mitchell Library), Ernest Bailey, ‘Narrative of Life Aboard an Australian Troopship, 22 October–28 December 1918,’ MLDOC 1284.

- Public Record Office Victoria, ‘Diary of Nurse Susie Cone, 1918–1919,’ VPRS 19295.

- Scarfe, J. (2013, 2018), ‘Cecil, Edith Ruth,’ East Melbourne Historical Society.

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS

- The Argus (Melbourne, 8 Aug 1934, p. 9), ‘Many A.I.F. Men Remember the Boonah.’

- The Brisbane Courier (4 Oct 1918, p. eight), ‘Wyreema’s Withdrawal.’

- Daily Herald (Adelaide, 12 Dec 1918, p. 3), ‘Boonah Quarantined.’

- Daily News (Perth, 11 Jan 1919, p. 3), ‘A W.A. Heroine.’

- The Journal (Adelaide, 8 Jan 1919, p. 1), ‘Personal.’

- The Observer (Adelaide, 28 Dec 1918, p. 33), ‘Wyreema Troops Landed.’

- The Register (Adelaide, 21 Dec 1918, p. 9), ‘Wyreema Troops Landed.’

- The Sydney Morning Herald (15 Oct 1918, p. 6), ‘For The Front.’

- Weekly Times (Melbourne, 18 Jan 1919, p. 43), ‘Died at Their Posts.’

- The West Australian (Perth, 12 Dec 1918, p. 7), ‘Pneumonic Influenza.’

- The West Australian (Perth, 13 Dec 1918, p. 7), ‘Vessel to Be Detained Indefinitely.’

- The West Australian (Perth, 16 Dec 1918, p. 6), ‘Pneumonic Influenza.’

- The West Australian (Perth, 22 Jan 1919, p. 6), ‘To the Editor.’