QAIMNSR │ Staff Nurse │ First World War │ Egypt, HMHS Essequibo, England & HMHS Glenart Castle

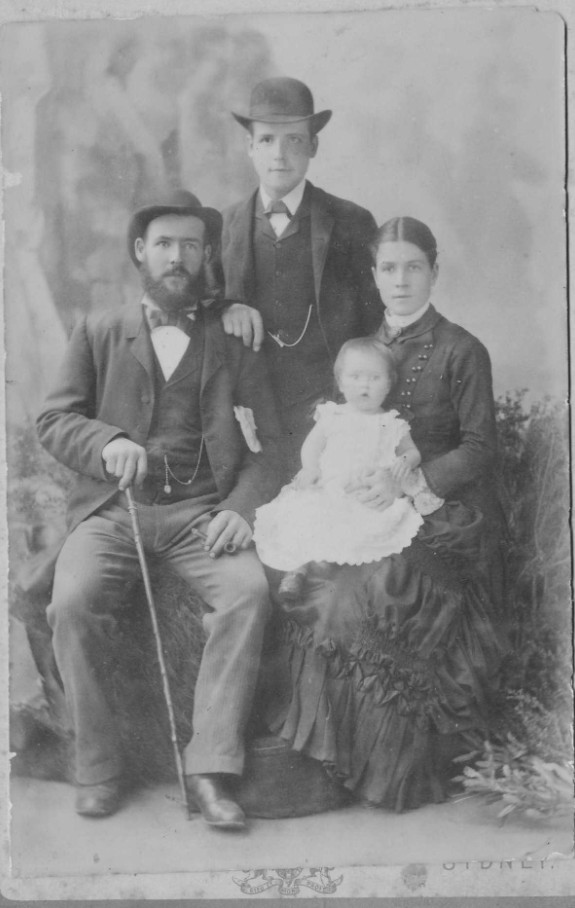

FAMILY BACKGROUND

Edith Blake, known within her family as Edie, was born on 22 September 1885 in a cottage hospital in Darlington, central Sydney. She was the first of three daughters born to Catherine Canham (1859–1947) and Charles Blake (1858–1938).

Catherine Canham was born on Parramatta Street in central Sydney and grew up in Waterloo. Her father was John Canham from Cambridge, England, who worked as a blacksmith, and her mother was Margaret Deeley from Galway in Ireland. She had an older sister, Agnes.

Charles Blake was born in Dallinghoo, a village in Suffolk, England. In 1873 he embarked upon a career as a merchant seaman, sailing to Hong Kong, Calcutta, Singapore and Manila. On 28 October 1879 he arrived in Sydney as a crew member on the Northumberland and stayed behind when his ship returned to England.

Charles met Catherine and the two were married on 15 November 1884 at St. Peter’s Church in Woolloomooloo. Ten months later Edith was born. A second daughter, Grace, followed in 1887, and in 1896 Catherine gave birth to their third daughter, Alice May, known in the family as Queenie.

Clearly a man of entrepreneurial drive, Charles established a delivery business, Messrs. Blake and Co., which sold milk for the Farmers’ and Dairymen’s Milk Company Ltd. By 1992 the family was living at 26 Abercrombie Street in Redfern, and Charles had attained a degree of independence. On 19 April of that year he took the family to England visit his relatives in Suffolk. They departed Sydney on the Kaiser Wilhelm II, arrived in Southampton on 2 June, and returned to Sydney on 18 December.

In 1900 Charles became the manager of the Sydney premises of the newly established Dairy Farmers’ Cooperative Milk Co. on Regent Street in Redfern, and by 1903 had opened his own shop selling groceries and milk at 6 Enmore Road in Marrickville. In 1914 he acquired liquor and tobacco licences and operated refreshment rooms at 273 Elizabeth Street, close to Central Station. He sold the business in mid-1915 at a very tidy profit. By then the family had moved to a substantial allotment on Vista Street in Sans Souci, a southern suburb on Kogarah Bay.

NURSING

We do not know where Edith went to school, but we do know that by 1908 she had decided to become a nurse. After applying three times to the Coast Hospital in Little Bay, she finally secured an interview with the hospital’s matron, Alice Watson, and in November 1908 was taken on as a probationer.

In December 1911 Edith passed the Australasian Trained Nurses’ Association membership examination and completed her training on 15 November 1912. She remained on staff at the Coast Hospital and by 1914 was a junior sister on a salary of £80 per annum.

ENLISTMENT

In August 1914 war broke out in Europe, and soon hundreds of Australian nurses had volunteered their services. Edith was one of them. She applied to join the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS), but the number of applicants far exceeded the number of places, and she had to wait.

Edith’s opportunity came in April 1915, when she was named among 130 AANS applicants allotted to the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service Reserve (QAIMNSR), the British equivalent of the AANS. Also named were two Coast Hospital colleagues, Elsie May Graham and Essena Myra (Eena) Copeman, and a former trainee of the hospital, Evelyn Ellen Swannell, who had resigned a few months after Edith began her training.

On Easter Sunday 4 April Edith, Elsie, Eena and several other New South Wales QAIMNSR recruits caught an 8.00 pm train from Sydney’s Central Station. They were bound for Melbourne, where they would board a ship that would take them – so they thought – to England. They changed trains the following morning in Albury and were joined by Evelyn Swannell. The nurses arrived in the southern metropolis just before 1.00 pm.

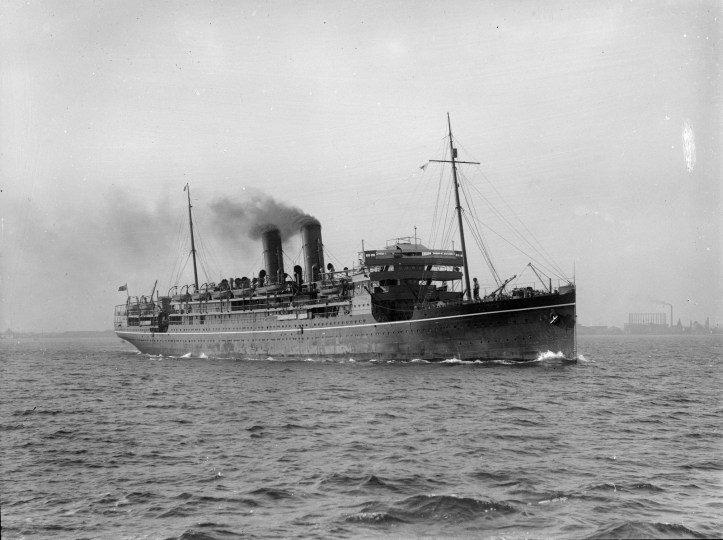

That afternoon Edith, Elsie and Eena visited the Melbourne Botanic Gardens. The following morning, 6 April, they met fellow recruit Wilhelmina (Minna) Solling, who was in charge of the nurses for the duration of their voyage, and made their way to Port Melbourne. There waiting for them was the RMS Malwa.

THE MALWA

Together with Evelyn Swannell and 16 other QAIMNSR recruits, Edith, Elsie, Eena and Minna boarded the Malwa and at 3.00 pm departed Melbourne. Edith and Evelyn shared a cabin, and in time the two of them became good friends.

After sailing via Port Adelaide and Fremantle, on the morning of 21 April the Malwa arrived in Colombo, Ceylon. As the ship was not leaving again until the following evening at 6.00 pm, Edith, Eena and Elsie booked an overnight trip to Kandy, a picturesque town situated on a plateau surrounded by mountains 100 kilometres inland. They had a splendid time, and arrived back in Colombo with half an hour to spare.

The Malwa set off again and within days had reached Aden – a “dirty, dusty, dry, desolate place,” according to Edith in one of her many letters home (Vane-Tempest, p. 43). Here the QAIMNSR nurses were informed that they would be leaving the ship in Suez. This came as a great shock; they had expected to sail to England to work there or in France, but now realised that they were being posted to hospitals in Egypt to nurse casualties of the Gallipoli campaign – or, as Edith referred to it, adopting the British designation, the Dardanelles campaign.

No. 1 AUSTRALIAN GENERAL HOSPITAL, HELIOPOLIS

After arriving at Suez around midday, the nurses were taken to shore amid cheers from those on board. A train was waiting for them at the port’s railway terminus. Passing through what Edith described as a desolate landscape, they travelled first north to Ismailia on the southeastern corner of the Nile Delta, then changed trains and travelled southwest to Cairo. They arrived at 11.30 pm and were taken by ambulance to the Heliopolis Palace Hotel, located in Heliopolis, a new suburb lying 10 kilometres northeast of central Cairo and named after an ancient Egyptian city.

Edith and the others arrived at the Heliopolis Palace Hotel at midnight. The Palace Hotel was the home of No. 1 Australian General Hospital (AGH), and here Edith and her colleagues would be based for the next two months – despite the fact that they were working for the QAIMNSR. After breakfast at 8.30 am on 3 May, Edith was detailed for duty at Luna Park, a former amusement park and one of several buildings close to the Palace Hotel into which the hospital had expanded in response to the huge numbers of casualties flowing in from the beaches of Gallipoli. Initially the auxiliary buildings were regarded simply as wards of the main hospital, but as it became obvious that the Gallipoli campaign would last longer than anticipated, they were soon better equipped and began to function in effect as independent hospitals.

Edith arrived at Luna Park and at 10.00 am became her work in the Rink, the lower section of the park, which was packed with row upon row of casualties – a total of 800, with only a handful of nurses to look after them. After sleeping in the afternoon, she went on night duty in the Pavillion, the upper section of Luna Park. She had responsibility for 73 patients by herself with no orderlies to help.

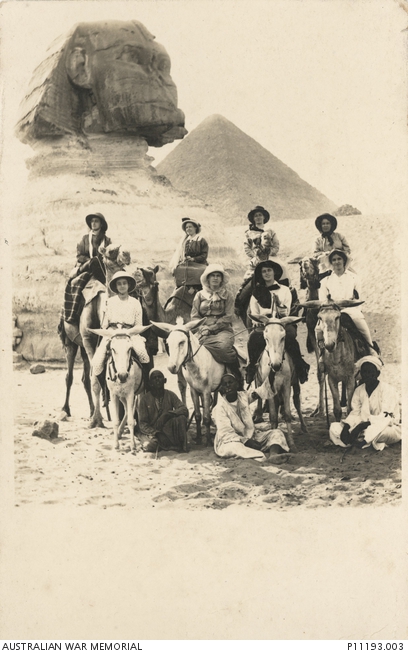

(Quote from K. Vane-Tempest; AWM P11193.003)

By mid-May there were 1,620 patients at Luna Park, looked after by a staff of six officers, 15 nurses and 40 other ranks. Edith had more than 500 patients on her ward, mostly with shoulder wounds or shattered fingers, all of whom could nevertheless help themselves to bed.

Within a month nearly 70 additional AANS nurses had arrived at No. 1 AGH from Australia on the Kyarra and the Mooltan. However, the fighting on the Gallipoli Peninsula had now ground to a stalemate, and far fewer casualty trains were arriving at Heliopolis. Edith was feeling underworked and longed for a change. It came when she was advised that she and 14 other QAIMNSR nurses were being sent to Alexandria, where they would be detailed for duty at either No. 15 or No. 17 General Hospital (GH), both British military hospitals. Although concerned that she might have to stay in Alexandria for the duration of the Gallipoli campaign, she was at least pleased at the prospect of nursing more severe cases than those she had looked after in Cairo.

Alexandria was the port of entry for the thousands of Gallipoli casualties treated in the dozens of Commonwealth military hospitals in Egypt. After passing through casualty clearing stations on the beaches of the Gallipoli Peninsula, the wounded men were ferried out to waiting hospital ships and transported to the island of Lemnos, 100 kilometres west of the peninsula. They were then either treated on Lemnos or transshipped to Egypt or Malta. Those transported to Egypt were hospitalised in Alexandria or Cairo, with the most serious cases remaining in Alexandria.

No. 17 GENERAL HOSPITAL, ALEXANDRIA

On 21 June 1915 Edith, Evelyn Swannell, Eena Copeman, Elsie Graham, Minna Solling, and the other 10 QAIMNSR nurses caught the midday train from Cairo and arrived in Alexandria at 4.00 pm. Edith and Evelyn were posted to No. 17 GH, based at Victoria College in the Ramleh district, while Eena, Elsie and Minna were posted to No. 15 GH, which had taken over the Abassieh Secondary School, on Rue Muharram Bey, close to the main railway station.

Alexandria. (AWM P11193.001)

Edith was assigned to the upper of two operating theatres and found her work more depressing than that at Heliopolis. “When I see eyes taken out, legs amputated,” she wrote home on 25 June, “you wonder what sort of existence that these poor men will lead as time goes on. It is far better to hear of them being killed, than maimed for life” (Vane-Tempest, p. 83).

Soon Edith was put in charge of the lower theatre. She developed a good relationship with Mr. Bourne, the consulting surgeon, and was fortunate enough to have excellent orderlies working for her. Following her work in the theatre, Edith was assigned with ‘specialling’ – giving one-on-one care to – a patient seriously ill with tetanus.

THE AUGUST OFFENSIVE

In August 1915 a new offensive on the Gallipoli Peninsula was opened by the Allies aimed at breaking the deadlock with the opposing Turkish forces. Its objective was to capture and hold two peaks on the Sari Bair Range above Ari Burnu (Anzac Cove) – Chunuk Bair and Hill 971 – giving the Allies a clear view across to the eastern side of the peninsula.

In support of the offensive, Australian troops would launch diversionary attacks at Lone Pine and the Nek; Australian, British, Indian and New Zealand troops would assault Sari Bair; New Zealand troops would assault Chunuk Bair; Australian troops would assault Hill 971; British troops would break out of their beachhead at Cape Hellas, south of Anzac Cove; and finally thousands of British troops would land at Suvla Bay, north of Anzac Cove, and attempt to link up with the Allies on the Sari Bair heights.

Between 6 and 29 August tens of thousands of Allied troops were thrown into the offensive. Unfortunately, Turkish forces had had warning of what was coming and had been able to reinforce their positions, and within days thousands of Allied soldiers had been cut down.

As the casualties mounted, bottlenecks ensued at every stage of medical intervention, and wounded men sometimes spent days waiting to be cleared from the beaches. The hospital ships were full, and the hospitals on Lemnos overcrowded and underequipped. Very soon thousands of casualties were pouring into Alexandria, with many hundreds ending up at No. 17 GH. “There is no news especially to tell you,” wrote Edith on 14 August, “except that the work is three times heavier, we only snatch an hour here & there off duty. The Dardanelles must be a large shamble, for the wounds are frightful. All the men in my ward have either lost an arm or leg, & their stumps are so painful … We have about 1700 patients now in hospital No 17” (Vane-Tempest, p. 99).

“THESE POOR MANGLED MEN…”

Edith wrote again six days later, as quoted in Vane-Tempest (pp. 99–100):

All the hospital ships have returned heavily laden with wounded [and] seemed to come together, the ambulances were seen coming up the road, one long line as far as you could see. I saw 15 cars coming at once. Oh! & how the poor wretches rolled in. No-one went off duty. Stretcher bearers worked till midnight … In the ward I’m in there is not one whole man. They each have either leg or arm missing, some have shoulder shattered as well. You don’t know how thankful I feel that we haven’t a brother, to see these poor mangled men, would make one’s heart ache. They are so hard to nurse. I’ve been in heavy wards and seen heavy cases, but never to equal this, nor so many. When they came in, I didn’t know which to commence on. Several have died. I found it hard to tell which wounds were the most needful of attention.

The August Offensive failed utterly. No gains were achieved, and thousands of men had died, with many more maimed for life. The commander of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, General Ian Hamilton, was replaced by General Charles Munro, who recommended the evacuation of the peninsula. The Gallipoli campaign was effectively over.

Nevertheless, the cases kept coming to No. 17 GH. They were no longer casualties of fighting, however, but casualties of disease and weather conditions. Between September and December, most of the deaths recorded at the hospital were from enteric fever, typhoid fever and dysentery. From late November frostbite became an enormous problem, and as many as 12,000 Allied troops were evacuated from the peninsula. Despite this, by 30 November the hospital had become “extremely slack,” according to Edith, as extra nurses and Voluntary Aid Detachment workers had arrived from England (Vane-Tempest, p. 122).

Meanwhile, in September Edith and nine of the other Australian QAIMNSR nurses who had come over on the Malwa had the opportunity of going to England to nurse. However, even though none of them particularly liked Egypt, they decided to stay, as their remuneration was so much better than it would be in England, and a few more months in the Land of the Pharaohs would not do them any harm. Edith did, however, express a desire to be detailed for sea transport duty on a hospital ship. When her friends Clarice Dickson and Dorothy Cawood, both former Coast Hospital trainees who had joined the AANS, were posted to HMHS Assaye and travelled to London, Malta, Salonica, Lemnos Island, Anzac Cove, Cape Helles and back to Alexandria, Edith was rather envious.

Christmas Day arrived, wet and windy. The nurses arranged a wonderful day for their patients. They shopped all week and gave each man a parcel. They hired cups and saucers, made egg sandwiches, and bought cake, fruit and nuts. They decorated the tables. Dinner was turkey and plum pudding, and also ale. The men pulled bonbons and were each given a cigar by the medical staff. There were concerts for the patients and staff, which were very much appreciated, and even a message from the King.

After 8.00 pm the nurses had their dinner: turkey and plum pudding served in blazing brandy; sweets fruit, bonbons, claret cup and liquor. They finished at 10.30 pm and then danced until 11.00 pm.

THE END OF THE CAMPAIGN

On the Gallipoli Peninsula troop numbers had been slowly drawn down since 7 December 1915. By 20 December Suvla Bay and Anzac Cove were evacuated, and the last Allied troops on the peninsula were withdrawn from Cape Hellas on 9 January 1916. By then, only 200 beds were occupied at No. 17 GH, of 2,500 available. At No. 15 GH, 500 of its 1,700 beds were due to close. Nevertheless, by early February No. 17 GH had become busy again. According to Edith, theirs was the only hospital that had any work to speak of.

(Quote from K. Vane-Tempest; AWM P11193.006)

After considering her options – in particular wondering whether to transfer to the AANS – on 4 April Edith renewed her QAIMNSR contract for a further 12 months. Evelyn Swannell renewed hers at the same time.

In early March Edith and Evelyn travelled south to the town of Luxor to visit Karnak, a vast temple complex of magnificent dimensions, and the Valley of the Kings. It took them 22 hours to travel by train from Alexandria, including a four-hour stop in Cairo.

In April Elsie Graham and Eena Copeman had gone on sea transport duty, and in May Edith and Evelyn Swannell put their names down too. By now work had become light again at No. 17 GH, save for an influx of Allied casualties from the Mesopotamian campaign. The campaign had begun at the end of 1914, and the Allies had won a string of victories as they pushed north along the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers towards Baghdad. The advance stalled in December 1915 when the Allies were besieged in the town of Kut, approximately halfway between Basra and Baghdad. Relieving forces were repelled, with heavy casualties, and it was these casualties that now flowed into the hospital.

As the year wore on, more and more Australian nurses left Egypt for England and France, and Edith was beginning to despair that she would ever go herself. Finally, in late September, she and Evelyn were told by Matron that they would soon be detailed for sea transport duty aboard HMHS Essequibo.

THE ESSEQUIBO

On 1 October 1916 Edith and Evelyn, accompanied by patients from No. 17 GH, departed Alexandria on the Wandilla, bound for Mudros on Lemnos Island. The two nurses were expecting to join the Essequibo, while their patients would be transferred to HMAS Britannic. When the Wandilla arrived in Mudros Harbour at midday on 3 October, the Essequibo was not there. It turned out that Edith and Evelyn would in fact meet their ship in Salonika (Thessaloniki) in northern Greece, and on the evening of 4 October the Wandilla set off for Greece’s second city.

Salonika was the site of a strong and growing Allied presence. Following the invasion of Serbia by Bulgarian, Austro-Hungarian and German forces on 6 October 1915, 110,000 Serbian troops had made their way to Corfu and eventually reached Salonika. Here they joined French, British, Russian and Italian troops in establishing the Allied Army of the Orient. The army was holding the front against Bulgaria and would eventually launch a successful offensive.

On the evening of 5 October Edith and Evelyn finally boarded their ship. The patients were embarked the following afternoon, and the Essequibo set off. It arrived in Malta on 10 October, and the wounded men were transferred to hospitals in Valetta. For the next two and a half months the ship shuttled between Salonika, Lemnos and Malta. During this time Edith met survivors of the hospital ships Britannic and Braemar Castle, respectively sunk and damaged by mines laid by German U-boats.

Christmas 1916 was spent at No. 21 GH, based in the Ras-el-Tin barracks, located on the peninsula between Alexandria’s Eastern and Western Harbours. After Christmas Edith, Evelyn and possibly the other nurses from the Essequibo were detailed for temporary duty at No. 21 GH before rejoining the Essequibo on 14 January 1917.

The Essequibo sailed for England on 16 January, arriving in Southampton on 26 January. Finally Edith was in England. She and Evelyn spent a few days’ sightseeing, visiting Netley Abbey among other places, before sailing for France on the morning of 31 January. It was snowing in the afternoon when the Essequibo arrived in Le Havre, and Edith and Evelyn joined in a snowball fight on deck. The following day nearly 500 patients were embarked, and the ship sailed again on 3 February.

When the Essequibo arrived in Dublin on 5 February, the patients were disembarked, and the nurses spent a very pleasant, but cold, afternoon being shown around the city. They departed again the next morning and late at night arrived in Liverpool. At midnight the ship tied up at Brocklebank Dock – a place with which Charles Blake had become very familiar 40 years earlier.

The Essequibo remained in Liverpool to be refitted, and for the next 10 days Edith visited various relatives in the Midlands, in London, and in Dallinghoo, Suffolk, where her father was born. She rejoined the ship, and on 20 February it set off for Halifax, the capital of Nova Scotia, Canada, with 575 Canadian casualties. The Essequibo reached Halifax on 1 March, and a small number of patients were disembarked, but it was not until 5 March that Canadian authorities were ready for the bulk of their men. While the ship was waiting at anchor, a snowstorm blanketed the deck in nine inches of snow, but it was so cold that Edith and Evelyn could not mould the snow into balls. Finally the remaining casualties were disembarked, and the nurses had an opportunity to explore Halifax. On 7 March, a contingent of Canadian nurses embarked, and the Essequibo sailed that night on its return journey to England.

After an encounter with a German U-boat off the southern coast of Ireland on 15 March, at the end of which the German crew wished the Essequibo a pleasant voyage, the ship arrived safely at Liverpool on 16 March and berthed at Canada Dock at 3.30 pm.

At this point Evelyn Swannell left the Essequibo, as she never could find her sea legs, and Edith asked to be put off too. However, her request was unsuccessful, and she and Evelyn were separated for the first time since the latter boarded Edith’s train in Albury. Evelyn went up to Scotland and Edith went back on board the Essequibo. She sailed once again to Halifax with around 500 Canadian patients and returned to Liverpool on the evening of 15 April.

HOME DUTY

When Edith and the other nurses disembarked the next morning they had been given orders to proceed to Dover, from where they would leave for service in France. However, to Edith’s great disappointment, in Dover she was told to return to Liverpool to collect her luggage, which she had stowed, and present at the Essequibo to receive new orders. These orders in turn were to return to London and await further orders, which likely entailed deployment to Salonika.

From London Edith wrote rather boldly to Ethel Becher, matron-in-chief of the QAIMNS, requesting that she be detailed for home duty in England. She particularly wanted to avoid service in Salonika, with its dysentery and malaria. In effect she threatened not to renew her contract, which had expired on 4 April, if her request were not granted. “I am now considering whether to resign or to sign on for a further period,” she wrote. “My hope is that I may be transferred to duty in England, & if this is possible I should be glad to know at your early convenience as I have already served six months on a hospital ship & eighteen months in Egypt” (quoted in Sedgwick).

Edith’s request was granted, and while she awaited her posting, she spent time exploring London and surrounds with her relatives and with Evelyn Swannell, whom she met at Liverpool Street Station. On 30 April she received orders to go to the Belmont Hospital in Surrey, around 18 kilometres south of central London. Not knowing what sort of patients she would be treating, she set out the following day.

BELMONT POW HOSPITAL

In late 1916 the Army Council had been looking for a suitable site for a German prisoner-of-war hospital and settled on the Belmont Workhouse (also known as the Fulham Workhouse, as it was managed by the Fulham Board of Guardians). The workhouse was located in the village of Belmont, today part of the London Borough of Sutton. The workhouse buildings, which dated from 1853 and were originally used as a ‘school’ for destitute children, were rapidly converted into a hospital with 92 beds for officers and 1,175 for other ranks. They also contained an internment camp with 90 beds for civilian enemy aliens awaiting repatriation. The hospital had only just opened when Edith arrived, and the first patients were not admitted until the day after.

Edith felt deeply ambivalent about looking after German prisoner-of-war patients. “I do not like them,” she wrote home. “But somehow when I am dressing their wounds I forget their nationality” (Vane-Tempest, p. 214). Her mixed feelings towards the Germans persisted for the entire six months she spent at Belmont.

In July 1917, while on a trip to nearby Croydon, Edith saw 30–40 German planes flying overhead, on their way to London. Later she heard that many bombs had been dropped during the raid, and that around 35 people had been killed and 140 injured. In her next letter home she expressed her horror. “We knew many people must be killed,” she wrote. “Oh Dear … to think I have to nurse these people. I never before felt it, but if I had been near them at that moment I would have killed them, for I had murder in my heart” (Vane-Tempest, p. 240).

Nonetheless, her own humanity overcame all such feelings, and when on duty her bitterness vanished.

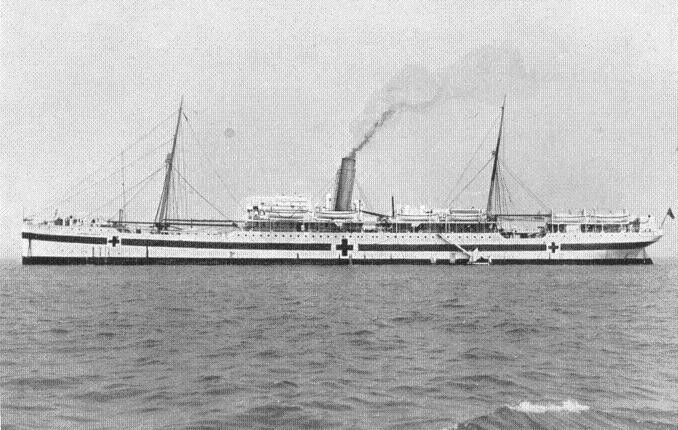

HMHS GLENART CASTLE

As the months passed by, Edith became disillusioned with the attitude of some of the medical staff at the hospital, considering them unfit. By October she had had enough and applied for a transfer. Her request was granted. On 12 November she entrained for Liverpool and three days later joined HMHS Glenart Castle. That afternoon, the ship took on Canadian patients and Edith was again bound for Halifax. She arrived in Nova Scotia on the afternoon of 26 November.

From Halifax the Glenart Castle recrossed the Atlantic and sailed to Malta via Gibraltar. For the next two months the ship followed a course by now familiar to Edith: from Malta to Salonika and back to Malta. Then to Stavros in northern Greece, around the Peloponnese Peninsula to Salonika, and back to Malta. After that, the route was repeated. On 6 February 1918 the Glenart Castle arrived at Avonmouth on the Bristol Channel, and the patients, nurses and some of the other staff disembarked. The ship then crossed the channel to Newport in south Wales to be refitted, and Edith began three weeks’ leave.

At 6.00 pm on 25 February 1918 the Glenart Castle sailed from Newport on its next voyage. It was headed for Brest, where it would embark wounded men. Just before 4.00 am on 26 February the ship was passing Lundy Island in the Bristol Channel. Suddenly, without any warning, a torpedo crashed into its starboard side. The engines stopped and the ship began to list. The wireless transmitter was disabled, so no distress call could be sent, and the starboard lifeboats were smashed to pieces. Only the portside No. 8 lifeboat was launched successfully.

The Glenart Castle sank in just seven or eight minutes. More than 150 of the 182 passengers lost their lives in the attack. Among them were Edith and seven other nurses.

REMEMBRANCE

A year after Edith’s death, her family placed a poignant memorial notice in the Sydney Morning Herald. It read as follows:

BLAKE – In loving memory of our daughter, Staff-Nurse Edith Blake (Q.A.I.M.N.S.R.), on active service aboard the hospital ship Glenart Castle, which was torpedoed and lost February 26, 1918.

For her there were no flowers

To adorn the unmarked surface of the waters;

The ocean alone decks her grave with gifts of pearl and shell.

And wreathes her brow with seaweeds rare.

Inserted by her father, mother, and sisters, Vista Street, Sans Souci.

Edith’s name is recorded on the Hollybrook Memorial in Southampton, England, which is dedicated to Commonwealth service personnel with no known grave. In Australia, her name is listed on the Commemorative Roll at the Australian War Memorial. And in the Sydney suburb of Kogarah, near Sans Souci, a small reserve is named the Edith Blake Reserve in her honour.

In memory of Edith.

SOURCES

- Aways from the Western Front (website), ‘From Edinburgh to Egypt: Nurse Elsie Russell’s War as Seen through the Lens.’

- Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Anzac Portal, ‘August Offensive on Gallipoli 6 to 29 August 1915.’

- James, Stuart, ‘First World War. UK, France, Canada and Egypt,’ Flickr.

- Lost Hospitals of London (website), ‘Belmont Hospital, 1 Homeland Drive, Sutton, Surrey SM2 5LY.’

- The National Archives (UK), WO-95-4144-5 Line of Communication Units HMHS Essequibo Jan 1917 to Dec 1918.

- Prince Henry Hospital Nursing & Medical Museum (website), ‘A Nurse’s Story: Sister Edith Blake.’

- Sedgwick, C. (2020), ‘Staff Nurse E. Blake, Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service, 26th February 1918, Age 32,’ published on the website ‘WW1 Australian Soldiers & Nurses Who Rest in the United Kingdom’ in the section titled ‘Hollybrook Memorial, Southampton, Hampshire, England War Graves.’

- Vane-Tempest, K. (2021), Edith Blake’s War: The only Australian nurse killed in action during the First World War, NewSouth Publishing, Kindle Edition.

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS AND GAZETTES

- The Australian Star (Sydney, 23 Nov 1889, p. eight), ‘Advertising.’

- The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, 18 Nov 1884, p. 1), ‘Family Notices.’

- The Daily Telegraph (Sydney, 2 Apr 1892, p. 4), ‘General News.’

- Dun’s Gazette for New South Wales (Vol. 11, No. 18, 4 May 1914, p. 421), ‘Wine Transfers Granted.’

- Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales (Sydney, 27 May 1914, [Issue No.90], p. 3139), ‘Colonial Wine Licenses.’

- Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales (Sydney, 10 Jun 1914 [Issue No.99], p. 3446), ‘Tobacco, Cigar, and Cigarette Licenses.’

- Government Gazette of the State of New South Wales (Sydney, 23 Jun 1915 [Issue No.112], p. 3647), ‘Tobacco, Cigar, And Cigarette Licenses.’

- Illawarra Mercury (Wollongong, 14 Apr 1892, p. 4), ‘Co-Operation.’

- The Sydney Daily Telegraph (23 Jul 1880, p. 2), ‘Shipping.’

- The Sydney Morning Herald (22 Dec 1911, p. 7), ‘Trained Nurses.’

- The Sydney Morning Herald (26 Feb 1919, p 10), ‘Family Notices.’