THE LAST DAYS OF SINGAPORE

On the morning of Tuesday 10 February 1942, with Japanese forces bearing down on their hospital in Singapore, Sister Pearl Mittelheuser and Staff Nurse Thelma Bell of the 2/10th Australian General Hospital (AGH) were told by Matron Dot Paschke that one of them would have to leave that day on an evacuation ship with wounded 8th Division soldiers. They tossed a coin, and Thelma called correctly. As much as she hated to leave her patients, she would get to go home.

Thelma was born in Drummoyne in Sydney and was due to turn 29 on 14 February. She had joined the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) in 1940 and had then enlisted in the 2nd Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF). In January 1941 she was attached to the 2/10th AGH and sailed with the unit aboard the Queen Mary to Malaya. After arriving on 18 February the 2/10th AGH established a hospital in Malacca. When the Imperial Japanese Army invaded Malaya in December, the hospital was relocated to Singapore. Now Singapore itself was on the cusp of falling.

Thelma was joining five other 2/10th AGH nurses who had been chosen to go by Matron Paschke. Staff Nurse Mary Campbell, known as Molly, was Thelma’s good friend. She was from Kilmore in Victoria and had the good (or bad) fortune to be born on Christmas Day. At 26, she was the youngest of the six nurses.

Staff Nurse Veronica Dwyer was born in Kyneton in Victoria and was 34 years old. Staff Nurse Iva Grigg was from Toowoomba in Queensland and was 18 days older than Veronica. Staff Nurse Violet Haig was born in Quorn in South Australia and had spent time in Western Australia. She was 30 years old.

In charge of the party was Sister Aileen Irving, who was from Wagga Wagga in New South Wales. At 35, Aileen was the eldest of the six nurses.

Later that day the six nurses were transported by ambulance to Keppel Harbour, where they boarded a makeshift hospital ship, the Wusueh. Major General H. Gordon Bennett, commander of the 8th Division, was on the wharf to see them off.

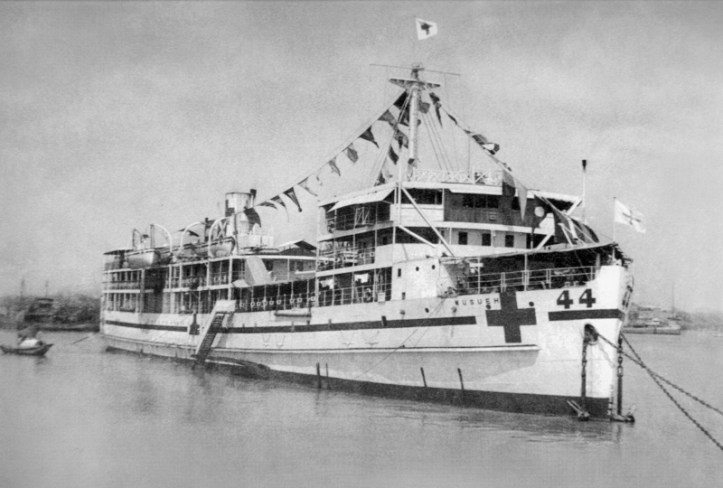

THE Wusueh

The Wusueh (also (mis)spelt Wah Sui, Wusei and Wu Suii) was later described by Thelma Bell as “a crazy old tub” and by Aileen Irving as “no larger than a Manly ferry steamer.” Built in 1930 for the China Navigation Company to ply the Yangtze river between Shanghai and Yichang, the flat-bottomed, twin-screw cargo vessel with room for 220 passengers was requisitioned by British authorities in April 1941 for use as a troop transport craft on the Malayan coast. Later in the year the Wusueh was transferred to Singapore and refitted as a hospital ship, complete with an operating room, wards, dispensary, and even a padded cell. However, although the Wusueh was painted white with red crosses, it was not (yet) internationally registered as a hospital ship and as such was not protected under the Hague Convention on Hospital Ships.

On board the Wusueh were as many as 350 wounded men, including perhaps 150 Australian 8th Division troops, a few RAAF men, and scores of British and Indian troops. They were lying so densely in the hold and all over the deck that the nurses had to step over one patient to get to another.

There were also a number of women and children on board. They had stayed in Singapore despite advice to leave – much to the disgust of one of the six nurses, who noted years later that had it not been for such complacency, many more wounded men could have been evacuated. Moreover, the women had embarked with trunks, suitcases and in some cases even golf clubs, and were unhelpful, even refusing to give up cabin accommodation to a pregnant non-British woman giving birth, who ended up doing so on deck.

While the Wusueh was still tied up, representatives of the Australian Red Cross Society came on board and supplied the nurses with soups, coffee, milk, soap, powder, stout, cotton wool and bandages for the patients. As the nurses had not brought any supplies with them, had it not been for the Red Cross, the Australian casualties would have had nothing else but bread and butter and tea.

Sometime on 11 February the Wusueh finally pulled away from the wharf and moved out into the roadstead beyond Keppel Harbour, where it stopped again. While it lay there at anchor, Japanese aircraft bombed the harbour, shattering the docks from which the Wusueh had recently embarked. That night the ship was lit up by the burning waterfront.

ESCAPE

Eventually, on 12 February, the Wusueh set out for Batavia, on the northwestern coast of Java, sailing in convoy with other evacuation ships. It was buzzed by Japanese aircraft but on each occasion their pilots respected the Red Cross and let it carry on.

One night during the journey the Wusueh came across two burning ships. The captain steamed over to see if he could provide assistance, but as no one could be seen it was assumed that the passengers and crew members had got away. As the crew of the Wusueh searched the sea, a Japanese cruiser turned its searchlights on them, but again the Red Cross was respected and the ship was allowed to proceed.

Three of the wounded Australians died during the voyage and were buried at sea. One of them was Pte. John Arthur Sandry of New South Wales, who was wounded on 24 January 1942 and buried at sea on 13 February.

BATAVIA

The Wusueh arrived at Tanjung Priok, the port of Batavia, on 15 February – the day that Singapore fell. As the ship entered the harbour, the nurses were struck by how crowded it was with other vessels. Many of them, like the Wusueh, had departed Singapore in the city’s final days and had managed to evade Japanese attacks.

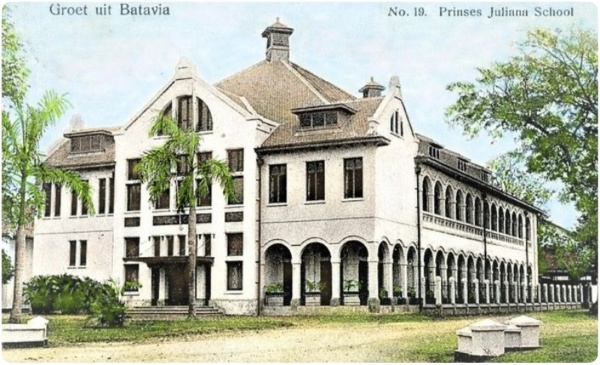

After disembarking, the nurses were taken to the Princess Juliana School, a Catholic girls’ school located at Weltevreden, around 10 kilometres south of Tanjung Priok. There they assisted the Ursuline nuns, who had established a medical facility.

Meanwhile, the casualties were disembarked from the Wusueh and taken to military hospitals. For the time being they were stuck in Batavia, but many would end up being transported to Colombo in Ceylon – some once again on the Wusueh, and some on other ships, including HMT Orcades and HMHS Karapara. The Karapara arrived in Colombo on 22 February 1942.

THE ORCADES

Two weeks earlier, the Orcades had set out from Port Tewfik in Egypt with 2,920 troops of the 7th Division, 2nd AIF. It was sailing as part of the ‘Stepsister’ movement of ships, during which most 2nd AIF personnel in the Middle East were brought back to Australia to help defend the homeland against Japan. Among the units on board the Orcades was the 2/2nd Casualty Clearing Station (CCS), whose chief surgeon, Lieutenant Colonel Edward ‘Weary’ Dunlop, would later become known throughout Australia. Eight of the unit’s AANS nurses were on board – Vida Paterson, Marcia Thorpe, Mary Finlay, Mary Wallace, Phyllis Pym, Margaret Marshall and Heather Wilson from Queensland, and Sister Vera Hamilton from New South Wales.

After the Orcades reached Colombo on 9 February, a decision was made to divert it to the Netherlands East Indies (NEI) in the face of rapid Japanese expansion into Southeast Asia, and on 15 February the ship arrived at Oosthaven in south Sumatra.

The Orcades did not stay long. Following the fall of Singapore, it was ordered to continue to Batavia in Java. On 16 February the ship arrived outside Tanjung Priok.

‘BLACKFORCE’

After waiting in the roadstead overnight, the Orcades moved inside the harbour on 17 February and pulled up to a wharf. Disembarkation of the military units commenced that afternoon and continued throughout the following day.

Once the units were ashore, they were hastily formed into ‘Blackburn Force,’ or ‘Blackforce’ for short, a formation that would serve as a nucleus of defence in Java under Lt. Col. Arthur S. Blackburn, who was promptly promoted to Brigadier. The officer in charge of the 2/2nd CCS, Lt. Col. N. Eadie, was appointed as senior medical officer to Blackforce, and the command of the CCS passed to Lt. Col. Dunlop.

On 19 February, with Batavia now under Japanese air attack, the staff of the 2/2nd CCS disembarked and were tasked with setting up the 1st Allied General Hospital at Bandung to care for Blackforce casualties. Sister Aileen Irving arranged for the six Australian nurses to travel to Bandung to assist at the hospital, and they entrained the same day.

BANDUNG

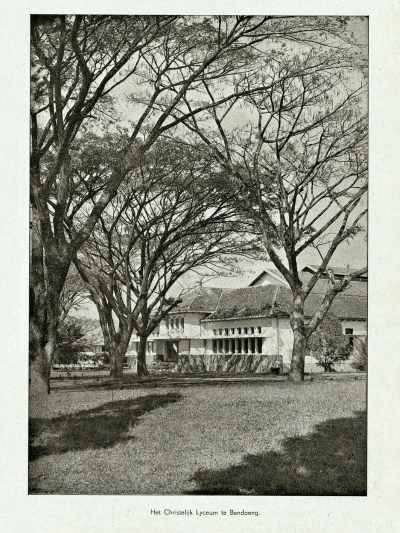

Bandung was an attractive town located 150 kilometres southeast of Batavia and set at a comfortable elevation of around 750 metres. After arriving, the 2/2nd CCS established the 1st Allied General Hospital in the Christelijk Lyceum (‘Christian Lyceum’), a high school on Dagoweg, where an RAF hospital was already operating. It was converted into a well-equipped and -supplied 1,200-bed hospital.

Bandung was under air attack too. After Thelma and another nurse were caught in the street during a bombing raids, they jumped into a dogcart and arrived at a deserted railway station close to a quinine factory. Unfortunately, this was one of the targets of Japanese bombing, and they were forced to keep going. They ended up in a Dutch home.

Despite having just arrived, it was decided that the Australian nurses should be evacuated. A Japanese invasion was feared and Dutch women and children were beginning to leave. On 21 February the nurses entrained for Batavia, travelling in cattle trucks due to the demand for places on board. In Batavia they were told that the Orcades was about to leave for Colombo, from where it would return to Australia. The ship’s captain agreed to take the nurses on board and gave them two hours’ notice to get ready. In the end, the ship sailed in such a hurry that their hastily packed luggage was left behind on the wharf.

COLOMBO AND HOME AGAIN

The nurses arrived in Colombo on 27 February in their working uniforms, plus a tin hat and gas mask, and not much else. The wounded and sick on board the Orcades were disembarked and taken to the 2/12th AGH at Welisara, just outside the Ceylonese capital. After that, the Orcades remained at port until 2 March, and it is not known whether the nurses were given shore leave.

Finally the Orcades left Colombo and reached Port Adelaide on 14 March. The 2/2nd CCS nurses disembarked the same day, but it would appear that the six 2/10th AGH nurses disembarked the following day. On 16 March they entrained for Melbourne and on 17 March arrived at Spencer Street Station.

It was cold and bleak in Melbourne. The nurses were dressed in their tropical uniforms, and nobody from the Army was at the station to greet them. According to Thelma, it was awful. They were, however, provided with coloured cardigans by the Australian Red Cross, which met all arrivals by train at Spencer Street Station. They then reported to Victoria Barracks on St. Kilda Road. Matron Gwladys Parker Field greeted them with a dressing down for their clothes and told them they were out of uniform!

That evening Thelma and Vi made their way to Sydney and arrived the next day. Iva travelled to Brisbane and presented herself at the Principal Matron’s office on 19 March. Molly, Veronica and Aileen stayed in Melbourne.

SOURCES

- 2/30th Battalion A.I.F. Association (website), ‘Return to Australia,’ ‘Repatriated,’ ‘Wah Sui,’ ‘Wu Suii/Wah Sui/ Wusei/Wusueh Hospital Ship evacuation of sick, injured to Ceylon February 1942.’

- Australian War Memorial, ‘WX11105 / W102 Ada Corbitt (Mickey) Syer, as a Captain, Australian Army Nursing Service and prisoner of the Japanese, 1941–1945, interviewed by Don Wall’ (1 Dec1989), S04057.

- Australian War Memorial, ‘Wallet 2 of 2 – Transcription of war diaries of Major John Edward Rea Clarke OBE, 1940–1942’ (2007), AWM2021.7.6.

- Goodman, R. (1985), Queensland Nurses Boer War to Vietnam, Boolarong Press.

- Lindsay, N.R. (1992, 2018), ‘First to Fight: 2/3rd Reserve Motor Transport Company AASC,’ from the website Historia.

- The National Archives (UK), Orcades 1939–42, BT-389-22-295.

- Naval Historical Society of Australia, ‘The Hospital Ships Buenos Aires Maru and Wah Sui.’

- Naval History (website), ‘Admiralty War Diaries Of World War 2, East Indies Fleet – January to March 1942,’ transcribed by Don Kindell.

- RAEME (website), ‘Thelma May Bell McEachern’.

- Thomas, D. A. V. (1988), Forty Years On! – As I Remember, originally privately published in Melbourne, now hosted on the website of the Abilene Christian University.

- Walker, A. S. (1961), Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 5 – Medical, Vol. IV – Medical Services of the Royal Australian Navy and Royal Australian Air Force with a Section on Women in the Army Medical Services, Part III – Women in the Army Medical Services, Chap. 36 – The Australian Army Nursing Service (pp. 428–76), Australian War Memorial.

- WikiSwire, ‘Wusueh.’

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS

- The Age (Melbourne, 18 Mar 1942, p. 3), ‘Women’s Section.’

- Daily Advertiser (Wagga Wagga, NSW, 2 Apr 1942, p. 2), ‘Back From Malaya.’

- Dubbo Liberal and Macquarie Advocate (NSW, 31 Mar 1942, p. 3), ‘Nurse’s Regret Was Leaving Singapore Men.’

- Record (Emerald Hill, Vic., 4 Apr 1942, p. 2), ‘Running Was Best Sport When Japs Flew Over. Local A.I.F. Nurse Describes Experiences in Java.’

- The Sun News-Pictorial (Melbourne, 19 Feb 1942, p. 16), ‘Nurses Tell of Singapore Ordeal.’

- The Sun (Sydney, 19 Feb 1942, p. 6), ‘Australian Nurses in Grim Escape Ordeal.’

- The Sydney Morning Herald (web edition, 11 Jun 2023), ‘On the toss of a coin, Army nurses traded life for death,’ by Sharon Bown and Kath Stein.

- Western Star and Roma Advertiser (Qld., 20 Feb 1942, p. 2), ‘Nurses Escape from Singapore in Small Chinese Steamer.’

- Wodonga and Towong Sentinel (Vic., 29 May 1942, p. 6), ‘Epic Courage of Two A.I.F. Nurses.’