THE FALL OF SINGAPORE

On the afternoon of Thursday 12 February 1942, the last 65 nurses of the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) were driven by ambulance to Keppel Harbour on the south coast of Singapore Island. With Japanese troops closing in, the nurses were being evacuated while there were still vessels leaving the island. Sixty of their colleagues had left the previous day on the Empire Star, and six the day before that on the Wusueh.

Thirty of the nurses belonged to the 2/10th Australian General Hospital (AGH), which had sailed to Malaya in February 1941 with thousands of 8th Division troops and had established a hospital in Malacca. Eight belonged to the 2/4th Casualty Clearing Station (CCS), which had accompanied the 2/10th AGH. The remaining 27 nurses were members of the 2/13th AGH, which had arrived in September. When the Imperial Japanese Army invaded Malaya in December, the units were relocated to Singapore Island. Now the island itself was on the cusp of falling.

The nurses walked the final few hundred metres to the harbour, as the ambulances could drive no further, such was the chaos all around. The port was thronged with people desperately trying to flee Singapore before the arrival of the Japanese. After passing through security checks, the nurses waited on the wharf. While they waited, they watched Japanese planes bombing the harbour and the city. Thick black smoke poured from burning oil installations on the small islands in the harbour.

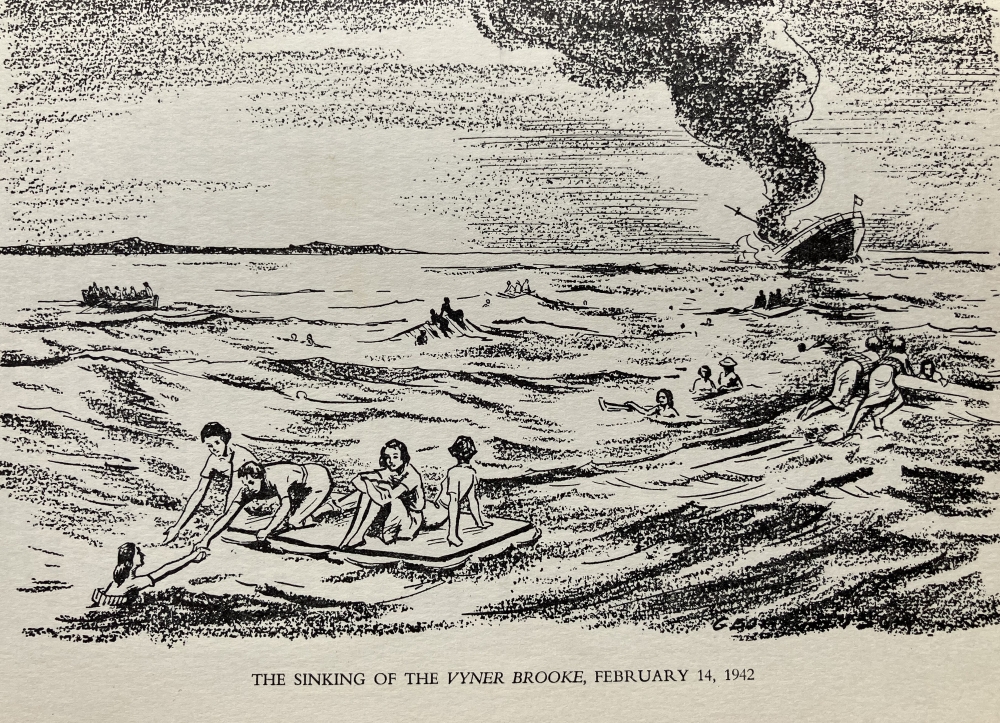

THE VYNER BROOKE

Eventually a tug took the Australian nurses out to a small coastal steamer, the Vyner Brooke, which had once been the Rajah of Sarawak’s private yacht. As darkness fell, the ship moved away from the wharf but stopped again in mid-harbour. Finally, under the cover of night, the captain, Richard Borton, negotiated the minefield protecting the harbour and steered the ship in a southwesterly direction towards the Durian Strait, the first part of the journey to Batavia in Java.

There were perhaps 250 passengers on board the Vyner Brooke. Apart from the 65 nurses and a number of military personnel, they were civilians, mainly women and children, with a smaller number of older men. They were crammed into all available spaces, and each had been issued with a lifebelt.

During the night, Captain Borton guided the Vyner Brooke slowly and carefully through the many islands that lie between Singapore and Batavia, and at first light on Friday 13 February he sought to hide the vessel among them – the better to evade Japanese planes. That morning the nurses were addressed by Matron Dot Paschke of the 2/10th AGH, who set out a plan to be followed should the ship be attacked. Essentially, the nurses were to attend to the passengers, help them into the lifeboats, search for stragglers, and only then leave the ship themselves. Since there were not enough places in the Vyner Brooke’s six lifeboats for everybody, if they could swim they were to take their chances in the water. They did at least have their lifebelts, and rafts would be deployed too.

In the afternoon a single Japanese aircraft flew over the ship and strafed it. Although no one was injured, the three lifeboats on the port side were holed. There would now be even fewer places available to passengers in the event of disaster.

UNDER ATTACK

Saturday 14 February dawned bright and clear. After another night of slow progress through the islands, the Vyner Brooke lay hidden at anchor once again. The ship was now nearing the entrance to Bangka Strait, with Sumatra to the starboard side and Bangka Island to port. Suddenly, at around 2.00 pm, the Vyner Brooke’s spotter picked out a plane. It circled the ship and flew off again. Captain Borton, guessing that Japanese dive-bombers would soon arrive, sounded the ship’s siren. The nurses, already wearing their lifebelts, put on their tin helmets and lay on the ship’s lower deck. The captain began to zig-zag through open water towards a large landmass on the horizon – Bangka Island. Soon, the bombers appeared, flying in formation and closing fast.

The planes, grouped in two formations of three, flew towards the Vyner Brooke. The ship weaved, and the bombs missed. The planes regrouped, flew in again, and this time the pilots scored three direct hits. When the first bomb exploded amidships, the Vyner Brooke lifted and rocked with a vast roar. The next went down the funnel and exploded in the engine room. As passengers swarmed up to the open air, a third bomb dealt the ship a last, fatal blow. With a dreadful noise of smashing glass and timber, it shuddered and came to a standstill, around 15 kilometres from Bangka Island.

EVACUATION

The nurses carried out their action plan. They helped the women and children, the oldest people, the wounded, and their own injured colleagues into the three remaining lifeboats, the first two of which got away successfully. However, the Vyner Brooke was now listing alarmingly, and as the third lifeboat was being lowered it juddered and swayed and crashed awkwardly into the water. A number of its passengers jumped out and swam, for fear that the ship might fall onto them.

After a final search, it was the nurses’ turn to evacuate the doomed ship. They removed their shoes and their tin helmets and entered the water any way they could. Some jumped from the portside railing, now high up in the air, while others practically stepped into the water on the starboard side. Some slid down ropes or climbed down ladders.

Once in the water, some of the nurses managed to clamber onto rafts and some grabbed hold of passing flotsam. Others caught hold of the ropes trailing behind the first two lifeboats or simply floated in their lifebelts. Meanwhile, the Vyner Brooke settled lower and lower in the water and then slipped out of sight. It had taken less than half an hour to sink.

LOST AT SEA

Twelve nurses lost their lives during or immediately after the attack or later at sea.

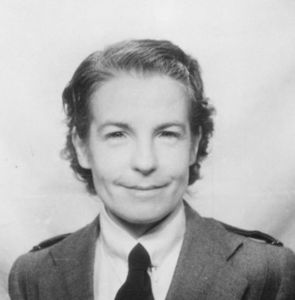

After helping passengers into the third lifeboat, Staff Nurse Mona Wilton, together with her best friend, Staff Nurse Wilma Oram, and their colleague Sister Jean Ashton, all three members of the 2/13th AGH, boarded the lifeboat and were lowered into the water. However, the Vyner Brooke was tipping over onto them, and things were sliding off the decks. The three jumped out of the lifeboat and swam for it. Mona Wilton and Wilma Oram were pulled under, but Jean Ashton got clear. Wilma came up again through the ship’s rails but Mona was nowhere to be seen. Wilma never saw her again. According to Jean, who witnessed it, poor Mona had been struck on the head by a falling raft and had simply floated away.

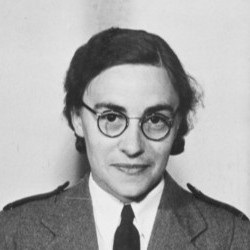

Meanwhile, Staff Nurse Mary Clarke and Sister Caroline Ennis of the 2/10th AGH, Staff Nurses Iole Harper, Myrtle McDonald and Merle Trenerry of the 2/13th AGH, Sister Millie Dorsch of the 2/4th CCS, and Matron Paschke had all reached a raft and were drifting along when Staff Nurse Betty Jeffrey of the 2/10th AGH swam over and joined them. Two crew members and four or five civilian women were also on the raft, and Caroline Ennis was holding two small children, a Malay boy and an English girl. The pieces of wood that were being used as oars were having little effect, so it was decided that whoever was able to swim beside the raft should do so, in order to lighten the load. Betty and Iole meanwhile took over the rowing.

After many hours the current carried the raft close to shore. The evacuees saw a lighthouse and a long pier before being carried out to sea again. Later, the current carried them in again, and they saw a fire on the beach. They knew then that at least one of the lifeboats had made it to shore. During the night a storm blew up, and the raft rocked and tossed until everybody was sick. It woke the little girl, who had slept most of the time in Caroline Ennis’s arms with the little boy, and she said to Caroline, “Auntie, I want to go upstairs.”

When daylight came the raft was as far out to sea as it had been to begin with. At this point, Betty Jeffrey, Iole Harper and the two crew members took their turn to swim alongside. After making progress towards the shore, the raft was suddenly caught in a current that somehow missed the swimmers and pulled swiftly out to sea. The nurses on the raft – Mary Clarke, Millie Dorsch, Caroline Ennis, Myrtle McDonald, Dot Paschke and Merle Trenerry – called out to Betty and Iole, but it was hopeless. They were now too far away and being carried further all the time. Betty and Iole never saw their six comrades again.

Of the five other nurses who were lost, only Sister Vima Bates of the 2/13th AGH and Sister Kath Kinsella of the 2/4th CCS were seen fleetingly in the water before vanishing, while Sisters Nell Calnan and Jean Russell and Staff Nurse Marjorie Schuman, all three with the 2/10th AGH, disappeared without a trace.

THOSE WHO were Lost at sea

- Sister Vima Bates (2/13th AGH, WA)

- Sister Nell Calnan (2/10th AGH, NSW)

- Staff Nurse Mary Clarke (2/10th AGH, NSW)

- Sister Millie Dorsch (2/4th CCS, SA)

- Sister Caroline Ennis (2/10th AGH, VIC)

- Sister Kath Kinsella (2/4th CCS, VIC)

- Staff Nurse Myrtle McDonald (2/13th AGH, QLD)

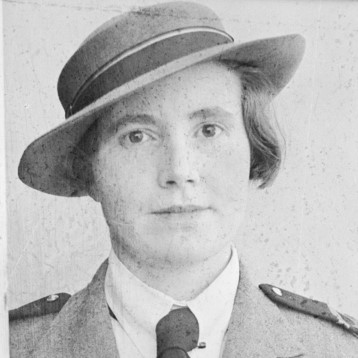

- Matron Dot Paschke (2/10th AGH, VIC)

- Sister Jean Russell (2/10th AGH, NSW)

- Staff Nurse Marjorie Schuman (2/10th AGH, NSW)

- Staff Nurse Merle Trenerry (2/13th AGH, SA)

- Staff Nurse Mona Wilton (2/13th AGH, VIC)

We remember them all.

SOURCES

- Angell, B. (2003), A Woman’s War: The Exceptional Life of Wilma Oram Young AM, New Holland Publishers.

- Arthurson, L., ‘The Story of the 13th Australian General Hospital, 8th Division AIF, Malaya,’ as reproduced by Peter Winstanley on the website Prisoners of War of the Japanese 1942–1945.

- Ashton, J. (2003), Jean’s Diary: A POW Diary 1942–1945, published by Jill Ashton.

- Darling (née Gunther), P. (2001), Portrait of a Nurse, published by Don Wall.

- Jeffrey, B. (1954), White Coolies, Angus & Robertson Publishers.

- ‘The Naval Evacuation of Singapore – February 1942,’ Naval Historical Review (June 2019), Naval Historical Society of Australia.

- Shaw, I. W. (2010), On Radji Beach, Pan Macmillan Australia.

- Simons, J. E. (1954), While History Passed, William Heinemann Ltd.