ESCAPE FROM SINGAPORE

On 11 February 1942, a contingent of 60 nurses of the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) was ordered to evacuate Singapore. Six of the nurses’ colleagues had left the day before on the Wusueh. Their remaining 65 colleagues would leave the day after on the Vyner Brooke.

Half of the contingent belonged to the 2/10th Australian General Hospital (AGH), which had arrived in Malaya in February 1941 aboard the Queen Mary and had established its hospital in Malacca. The other 30 belonged to the 2/13th AGH, which had arrived in September and was based initially on Singapore Island before relocating to Tampoi on the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula. After the Imperial Japanese Army invaded Malaya in December, both hospitals were evacuated to Singapore. Now Singapore itself was on the cusp of falling.

During these final days, with the battle for Singapore raging around them, the nurses were rarely off duty. Their hospitals were overcrowded, supplies were running short, and bombs and shells were falling all over the place. Yet the nurses’ spirit was undaunted, and they did not want to leave their patients.

Earlier, when Matrons Paschke of the 2/10th AGH and Drummond of the 2/13th AGH had called for volunteers to stay behind while their colleagues left, all had wanted to stay, so the matrons had the difficult task of drawing up lists and issuing orders. Thirty nurses from each hospital were ordered to go. They had no option of either staying with their patients or waiting until such time as all of the nurses could leave together. Staff Nurse Margaret Selwood of the 2/13th AGH exemplified the nurses’ attitude when she later said that although “those last days were sheer terror … when we had the order to evacuate we cried – it was so terrible to leave those brave men.”

The 60 nurses were told to pack their weekend suitcase and take their respirator, tin helmet and iron rations. They had to leave their trunks behind. Before long they were being driven in ambulances to the Adelphi Hotel, just opposite St. Andrew’s Cathedral in Singapore city, where they rendezvoused. They remained at the Adelphi Hotel while an air raid raged outside.

At Keppel Harbour

Eventually the nurses were driven to Keppel Harbour. All around them was destruction. The streets were full of rubble, and telegraph wires dangled disconsolately along the roads. Here and there locals sat mutely, just waiting, and all the while an air raid was taking place. “The situation we met when we arrived at the wharves was just like a nightmare,” stated one of the nurses (quoted in Shaw, p. 109). “Storage tanks were going up in flames all around us. The whole sky was illuminated and there were thick plumes of smoke.” The nurses waited in an air-raid shelter until the order came to board their ship, MV Empire Star.

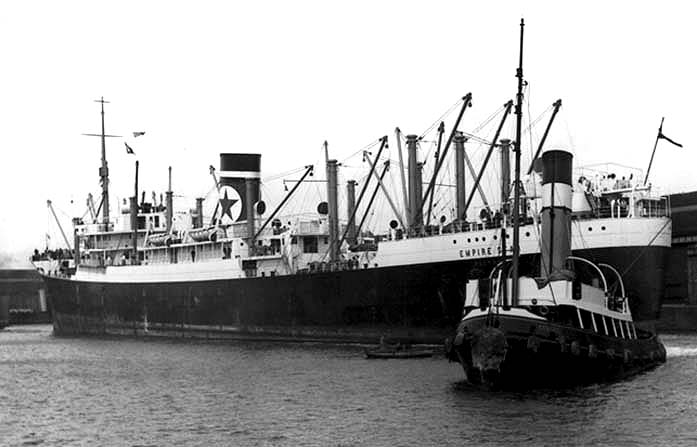

Captained by Selwyn N. Capon, the Empire Star was a British refrigerated cargo liner built in 1935 that originally carried frozen meat from Australia and New Zealand to England. It had become a troop carrier and had previously evacuated troops from Dunkirk, Greece and Crete.

While the nurses waited in the shelter, some soldiers broke open a crate of Christmas toys and threw teddy bears and other soft toys to them. Sister Kathleen McMillan of the 2/10th AGH picked up a toy rabbit in a bowtie and carried it back to Australia. Meanwhile, a medical officer belonging to their escort party was arguing with a guard about the nurses’ authority to board the Empire Star – as Staff Nurse Sara Baldwin-Wiseman of the 2/13th AGH recalled in her diary (Bassett, p. 139):

Our medical officer advanced to the gangway and demanded from the guard that we be allowed to embark. The guard flatly refused to allow any of us on board. He said that the ship was already grossly overloaded. Thereafter followed a heated argument for some time. The captain eventually agreed to take us providing we went down into the hold of the ship, where the refrigerated meat used to be carried.

Once they were cleared, the nurses boarded the ship via the gangway and a rope ladder with the assistance of two merchant seamen. Unfortunately, as Staff Nurse Maud Spehr of the 2/13th AGH was climbing the rope ladder, her haversack fell into the sea.

ON Board THE EMPIRE STAR

On board were more than 2,160 people, perhaps as many as 2,400. They were mainly British RAF personnel, whom General Archibald Wavell was sending to Java to help defend the Netherlands East Indies (NEI). There were also around 140 8th Division troops on board, some or all of whom were accused of being deserters and of having ‘rushed’ the ship, as well as 80 British nurses, a number of civilian refugees, and some 35 children. The ship also carried a considerable amount of RAF equipment and stores.

Before entering the hold, one of the 2/10th AGH nurses, who wrote as ‘Anonymous,’ beheld the devastated city:

Our last view of Singapore Harbour was vastly different from our first. The lovely sky was completely smoke-obscured, the incredible green of the sea hidden by a hideous film of oil, the sounds of battle from the shore and air were unpleasantly close – and, worst of all, a dead R.A.F. plane lay on the beach.

The Australian nurses were joined in the hold by 80 English and Indian nurses and Voluntary Aids of the Territorial Force Nursing Service, the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service and the Emergency Military Nursing Service. They were still recovering from their dramatic departure that morning from Alexandra Hospital. After dodging machine-gun bullets and narrowly avoiding being captured by advancing Japanese troops, they had boarded ambulances and set out for Keppel Harbour. After the ambulances were fired upon en route, the nurses had sought shelter in a sewer with a group of Indian troops. Eventually things had quietened down and they had been able to continue their journey.

The hold was accessed via a perpendicular steel ladder. Some of the Australian nurses found it smelly and dirty, while others did not mind particularly it. “Our quarters in the meat hold were quite clean, but they had a peculiar musty smell,” Masseuse Thelma Gibson of the 2/10th AGH later told The Australian Women’s Weekly. The nurses slept on their holdalls and belongings, and each had a blanket. They drank dixies of tea, which the men lowered down to them on ropes, and ate their ‘iron rations’ – dry biscuits and tins of bully beef, which some of them had managed to bring on board. There was a limited supply of water available. Some of the men threw down cartons of cigarettes – and toys, presumably some of those that had earlier been freed from their crate on the wharf. Maud Spehr caught a teddy bear that was thrown down and carried it home to Australia, later calling it Blitzer.

UNDER ATTACK

In the late evening of 11 February the Empire Star pulled away from the wharf and joined the Gorgon in the minefield beyond Keppel Harbour. Some of the nurses must have left the hold, for ‘Anonymous’ wrote that during the night they

watched the flashes from the artillery guns [and saw] the fires burning on the docks [which] seemed so immense that they must envelop the entire island.

At around 3.00 am on Thursday 12 February HMS Durban, HMS Jupiter, HMS Stronghold and HMS Kedah arrived at Keppel Harbour, collected troops, and at first light led the Empire Star and the Gorgon out into Durian Strait south of Singapore Island and set course for Batavia.

On the Empire Star, Captain Capon and his crew fully expected to be attacked from the air. The presence of Japanese aircraft was first reported at 8.50 am, as the convoy was about to clear Durian Strait. Just after 9.00 am the alarms were sounded, and six Japanese dive bombers descended from the sky. The guns of the convoy burst into action. One plane crashed into the sea and disappeared under the water. Another was hit and broke off from the squadron with smoke pouring from its tail.

Wave after wave of Japanese planes flew over the convoy, dropping bombs and strafing decks. Some of the ships were even attacked by kamikaze pilots. The Empire Star sustained three direct hits – one striking a lifeboat and the side of the ship, another the officers’ mess – while an incendiary bomb set the crew’s quarters alight; those on board fought the flames with buckets and hoses and managed to extinguish the fire. Following the bombing runs, the Japanese planes returned to strafe the decks.

Most of the Australian nurses were in the hold during the attacks, and some of the men made noble attempts to distract them. As ‘Anonymous’ recalled,

Several R.A.F. lads gallantly came down to entertain us. We held an impromptu concert, while a scout above deck would call ‘heads down’ as each wave of planes came towards us. Twice there were victorious shouts from above as our toy guns brought down raiders. Despite three direct hits, the magnificent work of the Captain and Merchant Marine crew kept us afloat … Following the attack we had work to do, several of the lads manning the guns had been killed, and many wounded, and two [or three] temporary hospitals were arranged for the care of the latter.

The Australian nurses had come aboard equipped with dressings, morphia, hypodermics and sulphanilamide and, together with a number of English doctors and the English and Indian nurses, were soon treating the wounded at emergency dressing stations in the hold. The 2/10th AGH nurses staffed one, the 2/13th AGH nurses another, and the English and Indian nurses a third.

At least two of the AANS nurses were on deck when the attacks began – Staff Nurses Margaret Anderson and Vera Torney of the 2/13th AGH, who had arrived in Malaya on 20 November 1941. Their instinctive actions as bullets flew around them later earned them the highest honours. In an interview with The Australian Women’s Weekly published in March 1942, Margaret Anderson described what happened:

While we were talking to some of our men on deck, the alert sounded and we went into the messroom for shelter. Bombs were dropped and a fire broke out. There was a badly wounded Australian boy who had been manning one of the guns. The place was chockful of smoke, so Tourney [sic] and I carried him out to the open deck and the two of us crouched over him. Then another wounded gunner was brought along and we tried to cover them both. Bullets were flying everywhere and we will never understand how we managed to avoid one ourselves. Later we got our patients back into the messroom, and a wonderful Irish doctor in the R.A.F. gave Tourney some morphia and a syringe and we used them as much as we could. Both our patients died, and I will never forget that mine managed to smile at me, and even give me a friendly wink. When we had the burials at sea it was the most pathetic and heartbreaking scene, and when we sang ‘Abide with Me’ we were all just too heartbroken for words.

On the Empire Star alone, 12 men lost their lives and dozens were injured during the attacks, in which as many as 70 or even 90 Japanese aircraft had been involved. Intermittent bombing runs continued for the next four hours, but these were high-level attacks from 2,000–3,000 metres carried out by heavy bombers. Dozens of bombs were dropped, some of which missed the Empire Star by mere metres. The final attack, carried out by a formation of nine aircraft, came at around 1.00pm. It was perhaps this attack that Staff Nurse Phyll Pugh of the 2/13th referred to in her story of the evacuation:

A last effort resulted in the Japanese dropping two one-thousand-pound bombs, one on each side of the ship. The Empire Star literally was lifted out of the water and when it righted itself, we heard only one of the two engines working. I stood beside my friend, Margaret [Selwood], when this happened. Looking at her I noticed a trickle of blood from her ear which had had its drum ruptured.

All the while Captain Capon had been taking evasive action. Thanks to Captain George Wright of the Singapore Pilot Service, who had remained on the Empire Star after it had cleared the harbour, and the Third Officer, Mr. James Peter Smith, Capon was being kept advised at all times of the manoeuvres of the attacking aircraft and their angle of attack, and was able to weave through the water or execute sudden reverses. By dint of his skill, and through sheer good luck, none of the high-level bombs struck the Empire Star and no casualties resulted from these attacks.

Remarkably, the ship was not attacked at all on the following day, Friday 13 February. It was afterwards learned that the Japanese pilots had instead turned their attention to a convoy of oil tankers. Meanwhile, in the hold, the Australian nurses had been playing cards but could not concentrate particularly well. They also spent time working four-hour shifts at the dressing stations – there were, after all, many wounded men to attend to.

BATAVIA

Later on Friday the convoy arrived at Priok Tanjung, the port of Batavia, but those on board the Empire Star did not disembark until Saturday 14 February. Shortly beforehand, Captain Capon had held a Thanksgiving Service, and all of those who could attend did so. Everyone understood what a miraculous escape they had had.

After the passengers disembarked, Captain Capon arranged for emergency repairs to be carried out on the ship. While the British RAF personnel were set to remain in Java, most of the civilian passengers ended up transferring to other ships. According to Maud Spehr, one particular civilian woman had 12 trunks on the wharf and was calling out for her 13th. A number of the nurses were disgusted at this and contrasted the woman’s obvious privilege with the experience of the alleged 8th Division deserters, who had by now been arrested and marched out to a camp.

Before long the Australian nurses were transferred to the Dutch ship Phrontis, which was bound for India via Ceylon. Here they spent the night in a clean, comfortable hold on straw mattresses. They were given fresh sandwiches, tea and cold water and treated with every consideration and kindness. Given their ordeal during the voyage from Singapore, it is unsurprising that the nurses, upon their return home, told a reporter for The West Australian that Batavia was “the most wonderful place on earth, a haven of peace after the everlasting noise of the blitz.”

Later on Saturday, or perhaps on Sunday, some of the nurses, including Staff Nurse Bettie Garrood of the 2/13th AGH, visited another ship, the Edendale. In a letter to her mother begun on Saturday (quoted in Arthurson, p. 114), Bettie describing meeting a certain Captain Gardner:

[He] was looking for his sister-in-law and tumbled over us. So we asked him if he would send cables, one to you and another to Mrs. Bentley [mother of Staff Nurse Nellie Bentley] – which he has since told us he did satisfactorily. He has been absolutely marvellous to us – located us again this afternoon and took us over to his ship [the Edendale], gave us tea, but what we enjoyed more than anything else was the use of his bathroom.

Some of the Australian nurses thought that they were going to return to Australia on the Phrontis. Others thought that they would first go to Ceylon to help at the 2/12th AGH, which was based at Welisara outside Colombo. However, the captain of the Dutch ship told the nurses that they had to return to the Empire Star. They refused, believing that they would be stuck in Batavia for some time while the ship was repaired. Only after they were assured that the Empire Star was in fact soon to depart, having been sufficiently patched up, did they return to the ship.

While the others were settling back into the dreaded meat hold, some of the senior nurses, including Sister Mary McMahon of the 2/10th AGH, went into Batavia, around 12 kilometres south of the port, to buy supplies of food with what little money the nurses had. They hired a motor vehicle and were taken to a large hotel, where they got out. Finding that the driver would not accept Malayan dollars, they went into the hotel to try to change it for Netherlands Indies guilders, but the Dutch clerk became agitated and told them that there was an air raid alert on and to take cover. They finally managed to change some money and went back to the driver, but he had disappeared. They bought what was available, mainly tinned food, and returned to the ship. As there was not enough, a meeting was held on the deck of the Empire Star, and the decision was made to have one meal a day at 11.00 am.

THE JOURNEY HOME

The Empire Star sailed from Tanjung Priok on Monday 16 February. Soon after departure, the nurses noticed a ship on the horizon, fast approaching the port. It was HMT Orcades carrying 7th Division troops to Java to reinforce the island against the Japanese. As the Orcades passed, the men on board waved frantically and called out “coo-ee.” When the Orcades departed Batavia again on 21 February, bound for Australia via Colombo, there were six AANS nurses aboard – the nurses who had been evacuated from Singapore on the Wusueh. They had arrived at Tanjung Priok on 15 February and were taken to the Princess Juliana School, a Catholic girls’ school located at Weltevreden, around 10 kilometres south of Tanjung Priok.

There were now far fewer passengers aboard the Empire Star, and the nurses were able to leave the hold and sleep in the fresh air. Many of them slept on the bridge. When at last they saw the Southern Cross, they knew that they were nearing Australia.

The Empire Star arrived at Fremantle on Monday 23 February. The 60 nurses were home. The ship anchored in Gage Roads and remained there until army headquarters was notified of the nurses’ arrival. Eventually some officers came aboard and took the nurses’ paybooks to ensure that they were in fact AANS nurses. Headquarters had decided that they would be taken on strength of the Returnees’ Depot in Claremont, just north of Fremantle, and detached to the 118th AGH in Northam, 90 kilometres northeast of Perth.

“Sadness Mixed With Joy”

“Sadness mixed with the joy of being home again,” wrote ‘Anonymous.’ “Our first question on landing was ‘Are the other girls home yet?’”

The six 2/10th AGH nurses who had left Singapore on the Wusueh and had then boarded the Orcades in Batavia eventually reached Port Adelaide on 14 March 1942. However, the ship on which the remaining 65 nurses had sailed, the SS Vyner Brooke, had been attacked and sunk by Japanese aircraft as it was nearing Bangka Strait, halfway between Singapore and Batavia. Twelve of the nurses were lost at sea, while the remaining 53 had washed ashore at various points along a stretch of coast on nearby Bangka Island, in the vicinity of the town of Muntok. Twenty-two of them had arrived close together in two lifeboats. On Monday 16 February they were shot by Japanese soldiers, who had occupied the island two days earlier as part of the invasion of the Netherlands East Indies. One of the nurses, Staff Nurse Vivian Bullwinkel of the 2/13th AGH, survived the massacre and after two weeks joined the remaining 31 nurses in captivity.

The 60 nurses finally disembarked and, before being transported to Northam, were taken to lunch at the 110th AGH in the Perth suburb of Hollywood. Either before or after arriving at the 110th AGH, they were interviewed by newspaper reporters, and the first stories of their safe return to Australia appeared the following day, Tuesday 24 February. The West Australian reported that all of the nurses looked remarkably fit, despite their terrifying experiences, and showed little outward sign of the ordeal that they had experienced. Some had on their working uniform, others, like Sheila Daley of the 2/10th AGH, their dress uniform. Some had collected a miscellaneous assortment of luggage, while others had very little. Each nurse had her tin helmet – described by one nurse as “the best friends we’ve got.” Incidentally, following the abolition of the rank of staff nurse in February 1942, backdated to 1 December 1941, the staff nurses among the 60 now held the rank of sister group 2, while the sisters held the rank of sister group 1.

Sometime after lunch at the 110th AGH, the nurses were taken to Northam, where they were provided with new uniforms and kit. While they were there, some army lads came to see them. They told them the worrying news that the Vyner Brooke had not arrived in Batavia. Other men told the nurses to ignore the men’s story.

Some of the nurses spoke to reporters again, and over the coming weeks stories continued to appear in the newspapers. On 7 March the West Australian quoted one of the nurses remarking that “we still have a sneaking desire to take cover when a motor backfires.”

The Nurses Separate

After two weeks at Northam, the 60 nurses were separated into two groups, as those from the eastern states prepared to return home. On 8 March 1942, 50 nurses from Victoria, New South Wales, Queensland and Tasmania entrained for Melbourne and arrived at Spencer Street Station on 12 March. Waiting for them were family and friends, all happy to welcome home their daughters, sisters, friends – and perhaps fiancées. As the women stepped from the train, they looked trim and spotless in their neat uniforms – the nurses in grey and the masseuses in navy blue – and were still carrying their tin helmets and gas masks. They were met by Principal Matron Field of Southern Command. That afternoon the Victorian and perhaps Tasmanian nurses were received by Lady Dugan, wife of the governor of Victoria, at Government House, while the New South Wales and Queensland nurses entrained for their home states. Meanwhile, the South Australian nurses and masseuses had arrived in Adelaide on 12 March.

The 21 nurses and five masseuses from New South Wales arrived in Sydney on 14 March. When interviewed by The Australian Women’s Weekly, Frances Cullen pointed out that they had worn their “battle dress for fifteen days, from Singapore to Fremantle, but [we] managed to rinse out our underwear in salt water. Our lipsticks came with us all the way, though we didn’t use them much.” She said how lucky they all felt to have made it home. “In fact, several of us bought lottery tickets when we arrived home.”

The six Queensland nurses – Monica Adams, Sheila Daley, Julia Powell, Phyll Pugh, Dorothy Ralston and Margaret Selwood – arrived in Brisbane on the same day, 14 March, and were also interviewed by newspaper reporters. According to the following day’s Sunday Mail, the nurses suggested that Australia’s complacency was amazing. “Only the women seem to have any idea of what war here would be like,” Margaret Selwood declared. “That’s because they have sons and husbands in Singapore and the Middle East.” Memories of Singapore were like a bad dream. The nurses described the attack on their ship by scores of Japanese bombers, which “rained hell on [us] from Singapore to Batavia.” They considered their escape to be miraculous.

Margaret Selwood praised the Australian soldiers of the 8th Division. “No one could ever say enough about those boys, who were fighting in Malaya,” she said. “Our chief job was not looking after their wounds but keeping them in bed long enough for wounds to heal. They were all itching for a fight again.”

We will remember them.

SOURCES

- Anonymous, ‘Malaya,’ in Wellesley-Smith, A. and Shaw, E. L., eds. (1944), Lest We Forget, Australian Army Nursing Service.

- Arthurson, L., ‘The Story of the 13th Australian General Hospital, 8th Division AIF, Malaya,’ as reproduced by Peter Winstanley on the website Prisoners of War of the Japanese 1942–1945.

- Bassett, J. (1992), Guns and Brooches: Australian Army Nursing from the Gulf War to the Boer War, Oxford University Press.

- Blue Star Line (website), ‘Blue Star’s M.V. ‘Empire Star’ 2.,’ particularly a transcript of Captain Capon’s letter to the mother of one of the survivors.

- Henning, P. (2013), Veils and Tin Hats: Tasmanian Nurses in the Second World War, BookPOD.

- RG Crompton (website), ‘Geoffrey Crompton: his war, part 2 Escape to Batavia and Ceylon: the voyage of the Blue Star’s MV Empire Star.’

- Luby. P., ‘Passage on the Empire Star,’ Remembrance (Nov 2022–23, vol. 12, pp. 46–57), Shrine of Remembrance, Melbourne.

- Martin, R. V. (2010), Ebb and Flow: Evacuations and Landings by Merchant Ships in World War Two, Brook House.

- Pugh, P. ‘Reminiscences of S/N Phyl Pugh (Mrs. Campbell),’ in Arthurson, L., ‘The Story of the 13th Australian General Hospital, 8th Division AIF, Malaya’ (edited by Peter Winstanley, 2009).

- Shaw, I. W. (2010), On Radji Beach, Pan Macmillan Australia.

SOURCES: NEWSPAPERS AND GAZETTES

- The Age (Melbourne, 13 Mar 1942, p. 3), ‘Women’s Section.’

- The Australian Women’s Weekly (28 Mar 1942, p. 7), ‘Home Again – A.I.F. Nurses from Malaya.’

- The Courier-Mail (Brisbane, 16 Mar 1942, p. 4), ‘They Were So Brave, It Nearly Broke Our Hearts.’

- The London Gazette (no. 35714, 22 Sept 1942, p. 4123).

- The Sun (Sydney, 15 Mar 1942, p. 4), ‘Still, They Smiled in Singapore.’

- Sunday Mail (Brisbane, 15 Mar 1942, p. 5), ‘Complacency Here, Say Returned A.I.F. Nurses.’

- Sunday Mail (Brisbane, 15 Mar 1942, p. 5), ‘Queensland Nurses Return Home.’

- The Sun News-Pictorial (Melbourne, 9 Mar 1942, p. 4), ‘62 Australian Nurses Back from Singapore.’

- The Sun News-Pictorial (Melbourne, 13 Mar 1942, p. 8), ‘Army Nurses Back from Singapore.’

- The Sun News-Pictorial (Melbourne, 2 May 1942, p. 12), ‘Epic Courage of A.I.F. Nurses.’

- The Swan Express (Midland Junction, WA, 15 Feb 1945, p. 5), ‘We Sailed for Singapore.’

- The Sydney Jewish News (10 Apr 1942, p. 5), ‘Australian Nurses Escape From Singapore.’

- The West Australian (Perth, 24 Feb 1942, p. 6), ‘Nurses Return.’